Governor Newsom’s “State of the State” speech today offered an abrupt scaling back of the state’s vision for its signature infrastructure project, high speed rail from Los Angeles to San Francisco:

[L]et’s level about high speed rail. I have nothing but respect for Governor Brown’s and Governor Schwarzenegger’s ambitious vision. I share it. And there’s no doubt that our state’s economy and quality of life depend on improving transportation. But let’s be real. The project, as currently planned, would cost too much and take too long. There’s been too little oversight and not enough transparency. Right now, there simply isn’t a path to get from Sacramento to San Diego, let alone from San Francisco to L.A. I wish there were. However, we do have the capacity to complete a high-speed rail link between Merced and Bakersfield.

In some ways, his position is a simple nod to fiscal reality. There aren’t enough funds right now to complete the project beyond this initial phase in the Central Valley anyway. Voters approved roughly $10 billion in bond funding in 2008, the 2009 federal “stimulus” bill offered another $3.5 billion, and Governor Brown and the legislature dedicated about 25% of cap-and-trade auction proceeds to continue building the system.

But that’s not enough to connect the Central Valley portion through the Pacheco Pass into San Jose, where it could then connect to the soon-to-be-electrified Caltrain into San Francisco. And it’s nowhere near the multiple billions of dollars needed to tunnel through the Tehachapi Mountains to connect to Southern California.

The key is the federal government: with Republicans in complete control of Congress from 2011 until last month, they were unwilling to match the state’s investment with federal dollars. While highway projects will get 90-100% funding from the federal government and intracity rail transit will get 50%, high speed rail has gotten just about 15% in federal matching funds — and only from that one-time 2009 stimulus grant.

If California had received closer to a 50% match from the federal government, the rail system would have the money to connect to the Bay Area. That link would provide significant economic benefits for Central Valley cities like Fresno and Merced by connecting them to the prosperous coastal economy. And it would create immediate benefits to bolster the long-term political support needed to eventually extend the system to Southern California.

But Governor Newsom’s speech today shows that he’s unlikely to spend much political capital to fight for these federal dollars from a congress that now features many California representatives, including the speaker, in control of the House of Representatives. It’s a position consistent with his 2014 interview in which he stated he would redirect funds from the system to other infrastructure needs.

Instead, his scaled-back vision presents a message that may confirm critics’ charges that the system is flawed and potentially infeasible. Some also worry that the new plan will embolden more litigants, arguing that the change in project vision violates the terms of that original 2008 bond initiative, although the courts have so far been deferential to state leaders on this question.

High speed rail backers will ultimately need a change in federal leadership come 2021 to get the necessary funds to complete the project — but it looks like they will have only tepid support from the state’s new governor in the meantime.

Huntington Beach, a non-compliant city on state housing goals.

California’s new governor is coming out firing on housing. First, Gov. Newsom’s proposed budget threatened to deprive cities of gas tax money if they don’t allow more housing to be built. And now today he’s suing Orange County’s Huntington Beach, population 200,000, for lack of compliance with state housing laws.

Technically, he’s not actually filing the lawsuit. Instead, he’s referring the case to the state’s Attorney General, Xavier Becerra, thanks to a relatively new state law, AB 72 (Santiago, 2017), which empowers such a lawsuit to be filed over local government intransigence on housing.

So why the need for the lawsuit? According to the San Francisco Chronicle, NIMBY influence on Huntington Beach’s city council caused the city to fall more than 400 units behind its state targets on housing, after city leaders scaled back approval of a high-density development in 2015. That proposal that would have otherwise allowed the city to comply with its housing target.

According to the state, in the three years since the rejection, the city has “taken no action to bring the housing element into compliance.” The city must now build 533 low-income housing units by the end of 2021 to meet updated state quotas.

In the old days, this lack of compliance would have been met with…nothing. There was essentially no penalty for non-compliance, and even when cities or counties complied, they often negotiated down their requirements to trivial amounts of housing or gamed the system in other ways to avoid having to make meaningful changes to their land use rules. But starting with SB 375 (Steinberg, 2008), which linked transportation funding to compliance, up through AB 72, the state has gotten more serious.

Which brings us to today’s lawsuit. It is a big deal, and not just for the potential impact on Huntington Beach’s land use policies, which will have to change if the suit is successful. More significantly, this lawsuit will be a wake-up call to cities across the state, motivating them to action on housing and also providing political cover for municipal leaders who know they need to do more to allow housing but are fearful (and captured by) their NIMBY constituents.

Furthermore, this probably won’t be the end of the lawsuits. According to the California Department of Housing and Community Development, at least four dozen other California cities also have not received state approval of their housing elements, as of the beginning of the year. Newsom is reportedly considering additional litigation against them.

So we can expect Newsom and Attorney General Becerra to be busy on housing in the coming months and beyond, ushering in a more combative era in the state’s effort to get local governments to allow new homes in their communities.

Governor Newsom is making housing a top priority. His proposed budget devotes significant resources to housing production and homelessness, including:

Governor Newsom is making housing a top priority. His proposed budget devotes significant resources to housing production and homelessness, including:

- $500 million for local governments to address homelessness

- $500 million (from $80 million originally) for the state’s low-income housing tax credit

- $500 million for “moderate-income” housing production

- $25 million for homeless Californians to access federal disability programs

But public cash alone won’t solve the problem, given the scale of the need. Along these lines, Gov. Newsom correctly identified local restrictions on new housing as a key barrier. To address the intransigence, he proposed the revolutionary step of limiting local government access to gas tax funds if the jurisdiction is behind on its housing production.

But how do you define a local jurisdiction “not meeting” housing production? Right now, it’s a bureaucratic threshold, set by the state for each region, which then in turn sets housing targets for each city and county in the region. Historically though, these “regional housing needs allocations” have been weak and easily gamed (though this process will become more stringent going forward, based on recent legislation like AB 686 and AB 72).

So if Gov. Newsom relies on an opaque and uncertain state-derived metric, his policy may not be that effective in actually encouraging new housing production. And cities and counties are somewhat limited anyway in how much housing actually gets built in their jurisdictions, particularly if they’re in areas without much housing demand.

A better metric would involve assessing local zoning and permitting processes near major transit stops or in “low vehicle miles traveled” areas (if a local jurisdiction doesn’t have much transit). Cities and counties can certainly control those two aspects of land use. For example, cities that have upzoned and streamlined permitting near transit would maintain their gas tax funding. Cities and counties that restrict what can be built or require multiple layers of discretionary review would then lose access to dollars.

Sen. Scott Wiener’s proposed SB 50 would get the state far down that path already, but Gov. Newsom’s use of that kind of budget mechanism would add political heft to the approach.

And as an added bonus, it might actually work in encouraging responsible local land use policies to boost housing production in the right places.

Pacific Gas & Electric, California’s largest investor-owned utility is about to declare bankruptcy, which could undermine the state’s climate goals. The utility faces massive liability for potentially causing the recent devastating Northern California wildfires.

If bankruptcy happens, California’s clean energy companies — from solar PV facilities to energy efficiency contractors to electric vehicle charging businesses — could soon lose one of their top customers and potentially see their existing contracts ripped up. And that means the state is losing a major investor in various climate programs.

Buzzfeed and E&E News [paywalled] covered this story in more detail, including some quotes from me.

Going forward, I hope the state and various local governments in PG&E service territory consider the following reforms:

- Break up PG&E’s electricity and gas divisions, with the long-term goal of phasing out natural gas use in the state. We mostly likely need to accomplish this phase-out anyway and move towards all-electric appliances and building. A breakup could hasten that progress.

- Buy out PG&Es assets and form municipal utilities. San Francisco is already exploring purchasing the “sticks and wires” in the city to form its own utility. Municipal utilities in the state tend to have cheaper rates and often more aggressive clean energy policies (such as Sacramento Municipal Utility District), so this could be a good move overall for ratepayers and the environment. Although it’s worth noting that PG&E is one of the cleanest utilities in California already.

- Revamp liability for wildfires going forward. Right now, whichever party is responsible for igniting a blaze is 100% liable for all damages. But what about property owners who failed to maintain and “fire-harden” their buildings? What about local officials that allow development in high-risk fire zones? What about polluting companies that caused climate change, which exacerbated the fires’ intensity? Liability should fall on these parties, too, giving them incentive to correct their actions going forward and hopefully reduce the severity of future wildfires.

These reforms would be a welcome outcome from an otherwise unfortunate situation. In the meantime though, it’s hard to foresee an outcome of PG&E’s death spiral that won’t at least temporarily slow our climate progress in California.

It took five years, but California has finally ditched an outdated and counter-productive metric for evaluating transportation impacts under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). With the guidelines finalized on December 28th, a mere half-decade since the passage of SB 743 (Steinberg) in 2013, the state will ditch “auto delay” as a measure of project impacts and instead measure overall driving miles (VMT). You can see the new guidelines Section 15064.3.

It’s a big deal. Now new projects like bike lanes, offices, and housing will be presumed exempt from any transportation analysis whatsoever under CEQA if they are within 1/2 mile of major transit or decrease driving miles over baseline conditions. That means significantly reduced litigation risk and processing time for these badly needed infill projects.

Sprawl projects, meanwhile, will need to account for and mitigate their impacts from dumping more cars on the road for longer driving distances. Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) explored one such mitigation option in the form of a VMT “mitigation bank” or exchange in the recent report Implementing SB 743, where developers could pay into a fund to reduce VMT, such as for new transit or bike lane projects.

Sprawl projects, meanwhile, will need to account for and mitigate their impacts from dumping more cars on the road for longer driving distances. Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) explored one such mitigation option in the form of a VMT “mitigation bank” or exchange in the recent report Implementing SB 743, where developers could pay into a fund to reduce VMT, such as for new transit or bike lane projects.

The one caveat is that due to political pressure, new roadway expansions are exempt from this requirement under the guidelines. It’s unfortunate, but those roadway projects will still need to undertake VMT analysis anyway for climate and air quality impacts, so perhaps they are not as exempt as their backers hoped.

You can learn more about these changes and what they mean going forward at a March 1st conference that CLEE is co-organizing in Los Angeles with the Urban Sustainability Accelerator at Portland State University. Shifting from Maintaining LOS to Reducing VMT: Case Studies of Analysis and Mitigation under CEQA Guidelines Implementing SB 743 will be a professional educational program for land use, transportation and environmental planners and attorneys in public, private and nonprofit practice, presented by expert practitioners.

- When: Friday March 1, 2019

- Where: Offices of the Southern California Association of Governments, Los Angeles

Topics to be discussed include:

- VMT impact analysis (methodology; appropriate tools and models, determining impact area)

- VMT significance thresholds (project effects, cumulative effects)

- VMT significance thresholds (project, cumulative)

- VMT mitigation strategies (project level, programmatic, VMT banks and transaction exchanges, legal and administrative framework)

Space is limited to 70 people to attend in person; registrants can view the program online streaming concurrently or subsequent to the program.

Registration Fees:

- Free Staff of state, regional and local governments sponsoring the SB 743 implementation assistance project and of their member governments (use link below for information about affiliations qualifying for free registration)

- $30 General registration, not seeking professional education credits

- $90 Planners seeking 6 AICP credits* ($15/credit)

- $210 Attorneys seeking 6 MCLE credits* ($35/credit)

*The organizer has accreditation for six hours of California Mandatory Continuing Legal Education (MCLE) credits and is seeking accreditation for six hours of AICP credits.

You can learn more about this conference here and can proceed directly to the online preregistration form here.

As 2018 nears its end, here are my Top 6 developments in climate & energy policy this year:

-

- Worldwide greenhouse gas emissions increase. Let’s start with the bad news for 2018: emissions are rising like a “speeding freight train,” primarily due to more coal-fired power coming on line for India and China, plus more energy use in the United States. Emissions are expected to increase 2.7 percent in 2018, according to research published by the Global Carbon Project. Meanwhile, a U.N. report in October indicated that the world may have just about a dozen more years to get emissions under control enough to avert disastrous warming. These reports should be concerning to everyone.

- Solar PV hits policy and deployment bumps but with long-term growth potential. With declining policy support worldwide, including costly tariffs on solar PV in the U.S., solar PV leaders have seen a downturn in 2018, for the first time in recent memory. Globally, according to the Frost & Sullivan (F&S) report Global Renewable Energy Outlook, 2018, the world saw 90 gigawatts (GW) of new solar installations for 2018, which was a slight year-on-year decrease. Overall though, renewable capacity will see 13.3% annual growth in 2018. The report authors expect global investment in renewable energy for the year to be $228.3 billion, a slight increase of 0.7% over 2017. In the U.S., according to latest industry figures, the third quarter saw installed solar PV capacity experience a 15% year-over-year decrease and a 20% quarter-over-quarter decrease. However, total installed U.S. solar PV capacity is expected to more than double over the next five years. Overall, the picture is concerning but with a potentially positive long-term outlook.

- EV sales increase worldwide, with 1 million in the U.S. and the Tesla Model 3 finally unveiled. The chart below tells the largely encouraging story:

China leads the pack with 40% of all sales. Here in California, sales just reached half a million, with one million nationwide. Prices continue to fall, and the Tesla Model 3 became the #6 top-selling car in the U.S. in November. Of all the climate change news, this progress on vehicle electrification may be the most hopeful, although we’ll need to see even more rapid deployment over the next decade to get growing worldwide transportation emissions under control.

China leads the pack with 40% of all sales. Here in California, sales just reached half a million, with one million nationwide. Prices continue to fall, and the Tesla Model 3 became the #6 top-selling car in the U.S. in November. Of all the climate change news, this progress on vehicle electrification may be the most hopeful, although we’ll need to see even more rapid deployment over the next decade to get growing worldwide transportation emissions under control. - Electrification of transportation spreads to trucks, buses and scooters. The EV revolution has spread, with cheaper, more powerful batteries now making electric “micromobility” options feasible, such as e-bikes and e-scooters. 2018 was truly the year of the e-scooter, when it comes to city streets. And on the heavy-duty side, companies are unveiling previously unheard of electric models, such as Daimler Trucks North America making the first delivery of an all-electric delivery truck, the Freightliner eCascadia, while the California Air Resources Board last week enacted a new rule requiring transit buses to be all-electric by 2040. All told, it’s a positive development for low-carbon transportation.

- Movement to legalize apartments near transit in California and across the U.S. All the electrification we can muster on transportation won’t matter much if we don’t decrease overall driving miles. It’s a particular problem in the U.S., with so many of our major cities built around solo vehicle trips. So it was encouraging to see California attempt to legalize apartments near major transit with Scott Wiener’s failed SB 827 earlier this year (which started a productive conversation) and now a potentially viable version in SB 50. The movement is catching on around the country, as Minneapolis just voted to end single-family zoning. It’s long overdue and our only real hope to decrease driving miles.

- Trump rollback proposals increase but face judicial setbacks. Trump’s attack on environmental protections made news all year, particularly his attempted rollback of clean vehicle fuel economy standards. The only bright spot is that many of his regulatory rollbacks are sloppy and getting shot down in the courts, as my colleague Dan Farber noted in a report and recent Legal Planet post. And with Democrats set to control the House of Representatives next month, pro-environment legislators are set to have more negotiating power on everything from the budget to enforcement to policy oversight.

So the trends overall are uneven, with a lot for concern and also promising technology and policy momentum still in effect. 2019 could also greatly change this picture, with a potentially slowing economy and more private sector innovation on clean technology.

Overall, those who care about these issues have a lot to digest and ponder this holiday season, along with the cookies. See you in 2019!

The California housing debate took me to KQED-TV’s “Newsroom” program on Friday. You can watch my discussion with host Thuy Vu and State Sen. Scott Wiener, author of SB 50 to upzone areas near major transit, at the 18-minute mark:

This has been a relatively eventful year in California land use, given the state’s severe housing shortage, and I’ll be speaking about it this morning at the 14th Annual “CEQA Year In Review” Conference in San Francisco. The morning panel will cover “Streamlining CEQA for Housing Approvals.”

This has been a relatively eventful year in California land use, given the state’s severe housing shortage, and I’ll be speaking about it this morning at the 14th Annual “CEQA Year In Review” Conference in San Francisco. The morning panel will cover “Streamlining CEQA for Housing Approvals.”

I’ll cover the state’s relatively lackluster effort to date to streamline environmental review for infill housing projects, which has had limited success in allowing environmentally beneficial infill projects to avoid costly and time-consuming environmental review. And as my colleague Eric Biber has found, much of the problem traces to local government decisions to make approvals discretionary for larger projects, which automatically triggers the environmental review process.

I’ll also discuss potentially promising state-level effort to require upzoning around major transit, such as this past year’s AB 2923 to upzone BART-owned parcels as well as this coming session’s SB 50 debate. But even if the state can accomplish mandatory upzoning, locals will still try to stop new projects by instituting lengthy approval processes with multiple veto points. So the next phase in the battle to address the housing shortage will probably be to limit local permitting discretion over projects near major transit.

I look forward to the discussion and hope to see you at the conference today!

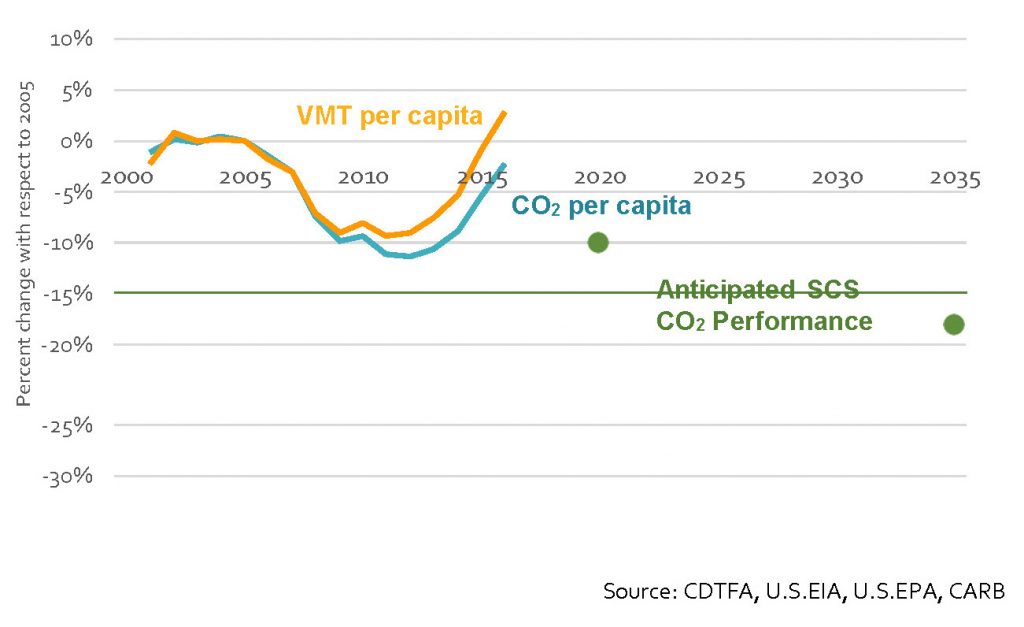

California’s major urban regions are falling behind in getting people out of their solo drives in favor of walking, biking, transit and carpooling, according to a major report last month from the California Air Resources Board. In short, the state will not meet its 2030 climate goals without more progress on reducing vehicle miles traveled (VMT):

This result comes despite the decade-old passage of SB 375 (Steinberg, 2008), which promised to reorient land use and transportation around reduced driving. The lone exception appears to be the San Francisco Bay Area, which has seen steadily increasing transit ridership and decreasing solo driving to work as a percentage, according to the report.

This result comes despite the decade-old passage of SB 375 (Steinberg, 2008), which promised to reorient land use and transportation around reduced driving. The lone exception appears to be the San Francisco Bay Area, which has seen steadily increasing transit ridership and decreasing solo driving to work as a percentage, according to the report.

What are the stakes if California can’t start solving this problem in the next decade? A U.N. report on climate change recently concluded that limiting global warming to 1.5 C would “require more policies that get people out of their cars — into ride-sharing and public transportation, if not bikes and scooters — even as cars switch from fossil fuels to electrics.” In order to keep the world on track to stay within 1.5 Celsius, the report stated that emission reductions would have to “come predominantly from the transport and industry sectors” and that countries couldn’t just rely on zero-emission vehicles alone.

Yet as the report shows, California’s current land use policies are not helping with this goal. We need to discourage development in car-dependent areas while promoting growth close to jobs, as SB 50 would allow. And at the same time, we need to invest in better transit service. Otherwise, California and jurisdictions like it around the world will fail to avert the coming climate catastrophe.

Last year, State Senator Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco) went right to the heart of California’s massive housing shortage in its job-rich centers with SB 827, which would have limited local restrictions on housing near transit. The bill went down in committee, a victim of election year politics and diverse opposition from wealthy homeowners, tenants rights advocates, and even a few misguided environmental organizations.

Last year, State Senator Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco) went right to the heart of California’s massive housing shortage in its job-rich centers with SB 827, which would have limited local restrictions on housing near transit. The bill went down in committee, a victim of election year politics and diverse opposition from wealthy homeowners, tenants rights advocates, and even a few misguided environmental organizations.

Now Senator Wiener is back at it with Senate Bill 50, which retains most of the heart of SB 827 but with a few changes to address the anti-displacement concerns over low-income tenants who might be evicted with new infill development.

Here is a summary of the provisions:

- Easing local zoning restrictions on new housing: SB 50 would eliminate local restrictions on density and on-site parking requirements greater than 0.5 spaces per unit for residential projects within one-half mile of “major transit” (rail and ferry) stops, as well as projects within one-quarter mile of major bus stops. It would also reduce the minimum floor-area ratio (percentage of the parcel that is developed) and height restrictions to nothing less than 45 feet within one-half mile and 55 feet within one-quarter mile of rail and ferry stops. Notably, these height limits are lower than the original version of SB 827 but basically consistent with the amended version before it was killed in committee.

- Geographic applicability: SB 50 is both more and less restrictive in its applicable geography than SB 827. The one-half mile radius is consistent, but now it no longer applies to all half-mile areas around major bus stops. Instead, the bill only applies its basic provisions to one-quarter mile of high-quality bus stops (defined as having peak commute headways of 15 minutes or less). It’s more expansive though in that it now applies to communities that are determined to be “job rich” and affluent, but not necessarily close to transit. The Governor’s Office of Planning and Research and Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) are charged with making the determination of what constitutes such a community, based on loose factors like proximity to jobs, high area median income relative to the relevant region, and high-quality public schools. And notably, the bill now applies to housing not just on residentially zoned land but land that may also be zoned commercial or mixed-use but allows for housing, too. But off the table (more below) are “sensitive communities” at risk of gentrification and displacement.

- Tenant protections & affordability requirements: the final amended version of SB 827 contained some strong anti-displacement provisions, and this bill picks up on those changes and expands them. For example, the bill does not apply to any properties that have tenants or have had a tenant within the last seven years. It also delays implementation in “sensitive communities” at risk of displacement until 2025, giving these areas from 2020 to 2025 to develop community-led plans to address growth and displacement. These communities would be determined by HCD based on factors like percentage of tenants below the poverty line, although it’s otherwise unclear how HCD would determine them. Finally, the bill includes minimum affordable housing requirement for projects requesting these local waivers (although that percentage is not yet determined yet in the bill).

With these changes, Sen. Wiener has already expanded the initial coalition in support — or at least not opposed at this point. For example, the powerful State Building & Construction Trades Council of California is supportive, as the bill explicitly allows existing local wage standards to remain unaffected. And tenants’ rights groups like Strategic Actions for a Just Economy in Los Angeles have not opposed the bill yet and have been in ongoing discussions with Sen. Wiener’s office. It otherwise seems inevitable though that the League of California Cities will oppose. So the question will be: will the coalition in support be powerful enough to override wealthy communities and their elected representatives, who will inevitably oppose?

In terms of the bill’s effectiveness, like SB 827 it would be a monumental shift in California housing policy that would address one of the core impediments to new housing construction: restrictive local zoning in job-rich areas.

Yet two provisions could undermine its effectiveness greatly, depending on how they are shaped during negotiations. First, the requirement to include a percentage of affordable homes in the buildings could render the provisions meaningless if that percentage is too high. For example, San Francisco’s voter-mandated inclusionary percentage of 25% affordable units for new development projects has contributed to a significant recent decrease in building permit applications (although other factors are at play as well), as SPUR recently documented.

In addition, placing off limits “sensitive communities” could also greatly limit its applicability without stricter and clearer criteria on how HCD will determine these communities and a sense of how many communities would be taken off the table. Otherwise the concept at first glance appears sound, as a way both to minimize opposition and reduce displacement risks in high-priority areas.

But overall, the bill retains the promise of SB 827 with a more inclusive process to bring on board more supporters. If SB 50 passes in something like its current form, it holds the potential to address the state’s housing shortage (and the emissions that result from long commutes from job-rich but housing-poor areas) in a fundamental way.