California faces a dual crisis: a massive housing shortage leading to displacement and spiraling economic inequality; and an increase in driving miles and related greenhouse gas emissions which threaten to undermine the state’s progress achieving its climate goals. Both of these crises were solidly addressed in Sen. Scott Wiener’s SB 50, which seeks to ease local restrictions on housing development near transit and jobs, in part so more residents can access transit and shorter commutes.

The bill sailed through its first two policy committees, with bipartisan support and only one vote against it in each. Labor unions, business groups, and key environmental groups like NRDC supported it. Yet as my Legal Planet colleague Jonathan Zasloff posted yesterday, Sen. Anthony Portantino, chair of the appropriations committee, unilaterally suspended the bill until January next year.

Sen. Portantino’s political career started out in the affluent Los Angeles suburb of La Cañada Flintridge, a community of mostly upper income homeowners. Residents’ general state of housing security contrasts sharply with the rest of the region, with the city’s average household income in 2015 at $214,496, compared to a median income in Los Angeles County that year of $54,510. The city was also ranked the 71st wealthiest city in the U.S. by Bloomberg. In short, it is a community with residents who aren’t likely to feel the brunt of the housing affordability crisis and in fact are likely benefiting from it through increased property values.

Sen. Portantino’s arguments against the bill cited some familiar objections, such as the bill would increase gentrification (false: new construction under the bill would almost exclusively occur in high-income areas), it’s one-size-fits-all (false: it is tailored to counties by population and areas by transit frequency, with the exception of a statewide provision permitting fourplex renovations), and that it will discourage transit expansion if a new rail line would come with strings attached on land use (to which the obvious response is: why would we want to spend taxpayer dollars on expensive transit lines to low-density communities?).

He also argued that incentives would work better to convince local governments to allow more housing. Yet what incentives does Sen. Portantino and others who espouse this view believe will work to induce city councils in upscale communities like Palo Alto, Beverly Hills and La Cañada Flintridge to allow multifamily housing, particularly for a variety for income levels? These are wealthy communities that will not be moved by the prospect of more state dollars. Indeed, in recent years, some of them (like Corte Madera in Marin County) even tried to secede from regional transportation agencies to avoid having to comply with state mandates to build low-income housing — that’s right, they’d rather sacrifice state transportation dollars than live next to low-income people.

Sen. Portantino’s unilateral action to hold the bill until next year now places the burden on Senate president Toni Atkins to override this decision and allow SB 50 a vote by the full senate. It also places a burden on Governor Newsom, who has pledged to build 3.5 million housing units in the state and expressed tentative support for the concept of SB 50. Yet as UCLA’s Luskin Center documented, the state’s current zoning only allows for 2.8 million units, and most of those units are likely in places where we wouldn’t want to see new growth, such as in far-flung, fire-prone regions. In short, the Governor cannot achieve his signature campaign goal without significant statewide upzoning, as SB 50 would produce.

Will state leaders step up to resuscitate to the bill? Is it too late at this point? Or will those currently suffering from housing insecurity and lack of affordable places to live have to wait until next year for a solution, when an upcoming election may darken its prospects for passage? Certainly other bills in Sacramento seek to address aspects of the housing shortage, but only SB 50 presented a comprehensive, meaningful solution to a crisis that is well past time to solve in this state.

I’ll be discussing SB 50 (Wiener) on KQED Radio’s Forum this morning from 9am. The bill heads to its final committee hearing this Thursday before a full vote in the California State Senate.

As I’ve written before, SB 50 is the state’s first and only major attempt at comprehensive “upzoning” (relaxing local restrictions on housing) near transit and jobs. It also recently added a provision to legalize the conversion of single-family homes into duplexes, triplexes or fourplexes anywhere in the state.

Tune in at 88.5 FM in the San Francisco Bay Area and weigh in with your questions. Even if you don’t live in the Bay Area, you can stream it live and call in or email with questions.

Yesterday was a big day for SB 50 (Wiener), the bill to upzone residential areas near transit and jobs. The bill faced a potentially hostile Senate Governance and Finance Committee, chaired by State Senator Mike McGuire from Sonoma County and author of the rival Senate Bill 4. Despite the treacherous path, the outcome was a decisive win with only one vote against (Sen. Hertzberg of Los Angeles), albeit with significant amendments to the bill.

The new bill language has not been released, but based on the committee discussion and follow-up statements from Sen. Wiener and his office, the amendments essentially appear to do two big things (among other changes):

- Exempt SB 50 from counties with populations less than 600,000, except for cities within those counties with populations over 50,000 that have rail or ferry stops (see the green/purple parts of the flow chart below)

- Legalize “by right” permitting of single-family homes into duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes across the state, albeit with only minimal demolition of existing structures allowed.

The amendments now make the overall bill relatively complex, but Berkeley-based artist Alfred Twu drew up this handy flow chart to explain how the bill will now work:

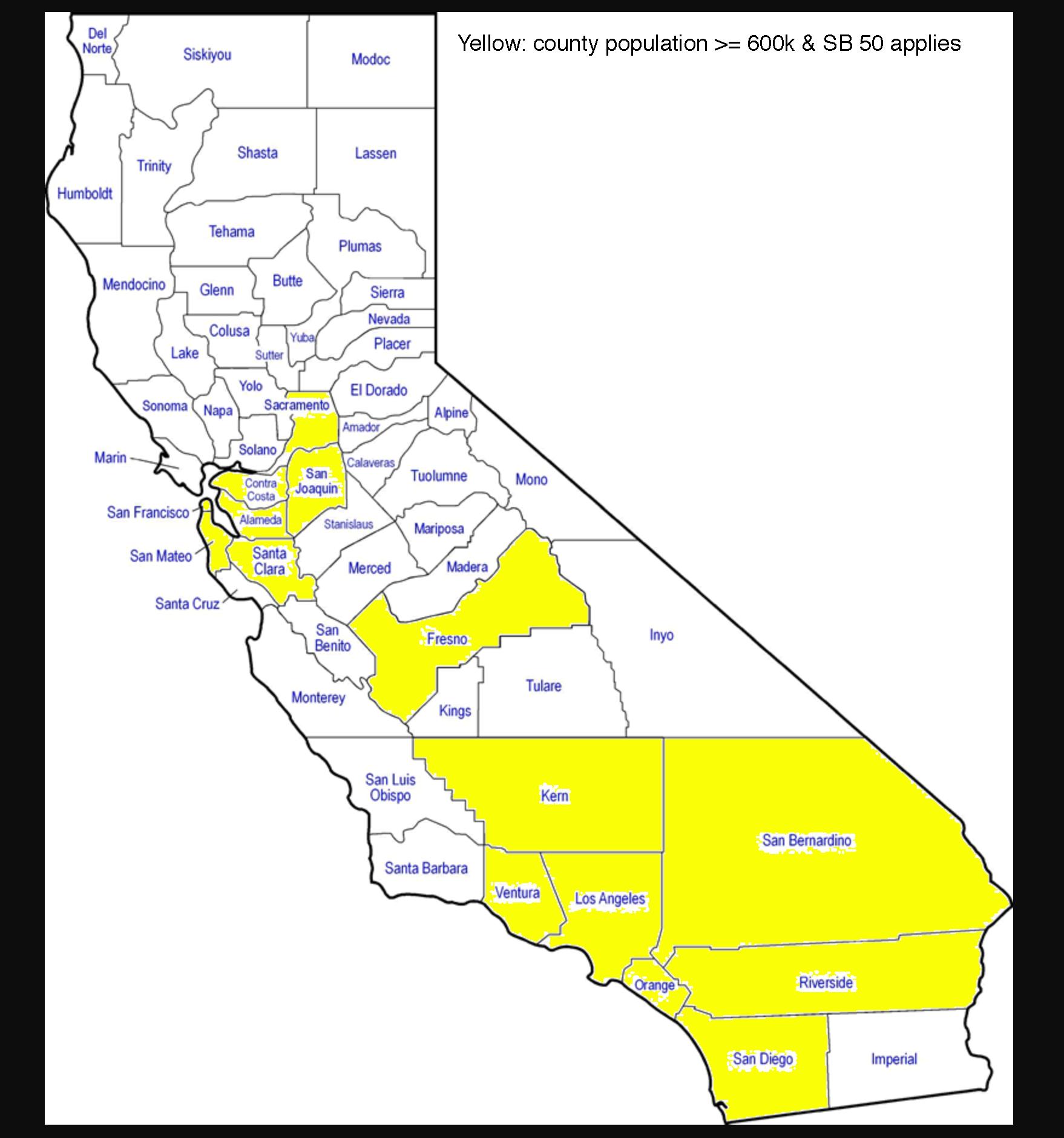

For a graphic on the counties now affected, here is a map from Barak Gila with the counties over 600,000 population (in which SB 50 applies) in yellow:

So did Marin County get a carve out, in a deal to merge the bill with county representative McGuire’s SB 4? Notable cities now apparently exempted from SB 50 include the SMART train and ferry stop in Larkspur and the ferry-stop towns of Sausalito and Tiburon. Yet San Rafael and Novato (two SMART train stops) are still covered by SB 50.

What about Sonoma County? Cities with SMART trains that no longer would be under SB 50 jurisdiction include Cotati, Rohnert Park, Cloverdale, Healdsburg, and Windsor. Still included are Petaluma and Santa Rosa.

In Southern California, Santa Barbara County’s Goleta and Carpinteria Amtrak stations also would not be covered by SB 50, while the City of Santa Barbara would still be affected.

Meanwhile, notable other cities with rail or ferry stops within those non-yellow counties, to which SB 50 will still apply, include Vallejo, Fairfield, Vacaville, Roseville, Rocklin, Madera, Modesto, Merced, Davis, Chico, Redding, and Salinas. And of course the remaining yellow counties represent major population and employment centers that could greatly increase housing production with SB 50 upzoning.

On balance, this new population criteria is not a bad compromise, as it means most of the core areas of California that prevent new housing are still affected. But the SMART train line is pretty well decimated by this compromise, as is the Santa Barbara Amtrak line. It’s a relatively small but painful price to pay, given the potential benefits statewide with the remaining areas.

Meanwhile, the fourplex by-right provision could potentially open up significant densification in California everywhere, a la the recent Minneapolis plan to end single-family zoning and allow triplexes city-wide. But could this new SB 50 provision encourage more high-density sprawl, with fourplexes in outlying areas that don’t have access to transit and therefore lead to more traffic and pollution? The original beauty of SB 50 (and its predecessor SB 827) was that it targeted transit neighborhoods to reduce overall driving miles. The fourplex provision could undermine those environmental benefits. Yet since the fourplexes (or other smaller divisions) can only involve minor demolition of existing structures (or building from the ground up on vacant parcels), the deployment may not be as sweeping as it might initially appear.

Overall, SB 50 cleared a major hurdle yesterday before its eventual advancement to the Senate floor, emerging relatively unscathed and with some potentially major new additions. If it passes that chamber, it will be on to the Assembly, with further carve-outs and compromises likely.

What’s the latest with California’s major proposed legislation to remove local restrictions on new housing near transit and jobs? I wrote back in December about Senate Bill 50 (Wiener), which would relax local requirements on density, parking, floor-area ratio and height (in some cases), for projects near transit and in high income “job-rich” communities that lack commensurate housing (read: Cupertino, home of Apple).

SB 50 also contains provisions to protect low-income renters from eviction from any new development under the bill and takes off the table (at least for the near future) large swaths of urban low-income areas deemed to be “sensitive communities.” For a visualization of what that means on the ground, see p. 11 (figure 5) of the CASA compact for a map of San Francisco Bay Area zones that would be exempted under this provision.

So how is the bill doing? Notably, SB 50 sailed through its first committee hearing last week with overwhelming approval. But it may face critical obstacles in its next hearing at the State Senate Governance and Finance Committee. That’s because that committee is chaired by State Senator Mike McGuire from Sonoma County, who authored a rival bill (Senate Bill 4) which would do much the same to relax local zoning near transit as SB 50, except with the big difference that it would exempt any “city with a population of 50,000 or greater that is located in a county with a population of less than 1,000,000” (which would exempt McGuire’s hometown of Healdsburg from the bill’s provision).

So the politics remain dicey going forward. The difference this year though is that Wiener has lined up powerful political support from organized labor, who like the job opportunities that would flow from more housing projects in urban areas. And by exempting in the near term “sensitive communities” with low-income tenants, Wiener has largely neutralized (for now) opposition from tenant groups who helped sink last year’s version, SB 827.

As a result, the opposition has so far been revealed as wealthy communities up and down California, who are resistant to allowing any new development or letting newcomers move in who can’t afford an expensive single-family home. They frequently use lines of attack like the bill is a “developer giveaway” or that proponents are “real estate shills.”

To counter these voices and win more support from advocates for low-income renters, Wiener has introduced amendments that tighten up the affordable housing requirements for any project that uses the bill’s provisions. Specifically, SB 50 now has ‘inclusionary zoning’ requirements in which developers with projects with between 20-200 units must make 15% of the units affordable to low-income residents (implemented on a sliding scale, with fewer units required if they’re available to extremely low-income residents), while 200-350-unit projects must provide 17% affordable units. Any project above 350 units must have 25% affordable units (also on a sliding scale depending on the income eligibility). Housing projects under 10 units are meanwhile exempt from providing any on-site affordable units, while projects of 10-20 units in size can pay in-lieu fees. With these provisions in place, the bill would likely lead to a significant deployment of subsidized affordable units to accompany new market-rate development.

But what practical effect will SB 50 likely have on the ground, assuming it can survive the messy politics and become law relatively intact? UC Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation and Urban Displacement Project conducted an interesting case study policy brief and found that any likely boost to new housing under SB 50 would mostly be small scale and in high-income communities, though that impact varies depending on whether other local restrictions are in place.

The UC Berkeley study involved a parcel and financial feasibility analysis on four representative neighborhoods in the state, with the following highlights:

- Developers will get a much higher return on SB 50 projects in upscale areas, even with the higher land costs, meaning that most projects will be built in these areas and not in low-income areas (as I argued back during the SB 827 debates last year).

- Most of the available parcels (at least in these four study areas) are too small to support big projects, meaning most development will likely be of the 12-unit or less variety; in addition, the bill’s restrictions on developing properties with tenants will likely take a significant number of parcels off the table (a good thing, from the point of view of protecting current tenants from eviction).

- High on-site affordable housing requirements (discussed above) will be financially feasible in upscale areas but could sink projects in lower-income neighborhoods that otherwise barely pencil, so Sen. Wiener may want to consider a less rigid approach to the affordable housing requirements and instead scale them based on the value of the project.

- Remaining local government restrictions, such as high setback requirements and bans on projects that cast too much shadow (which was a dealbreaker for an important housing project in San Francisco that the board of supervisors just killed because it would cast occasional shadows at an adjacent park), will still impede projects, even if SB 50 passes.

- Developers may choose to ignore the benefits of SB 50 if a local government has already made it easy to permit projects at the current, locally determined height and density limits, just to avoid a protracted permitting fight that would come with using new, state-allowed higher limits.

The findings from this study should be clarifying for the SB 50 debate going forward. First, they show the relatively limited impact that SB 50 might have on the ground, at least compared to some of the hyperbolic rhetoric and initial studies about the predecessor bill’s impact in specific areas.

Second, SB 50 will likely end up being a just step (albeit a big one) in the right direction on boosting housing supply to match demand. Further reforms (some under consideration in other bills being debated this session) will need to focus on streamlining the permitting process for projects consistent with this new zoning. Otherwise, local governments are likely to respond to SB 50’s passage by adding more steps to the permitting process in order to kill projects through delay and multiple veto points. State legislation may also need to address the other zoning restrictions on new development that SB 50 leaves untouched, such as the aforementioned setback and shadow limits.

California’s current housing shortage certainly didn’t happen by accident — it’s the result of a complicated web of politics that SB 50 and its backers are trying to undo, piece by piece. We’ll have to stay tuned as more studies assess the bill’s impact and Wiener entertains more political compromises to win over support.

The Two Hundred is a new industry-backed group with a familiar refrain: California’s housing shortage (and overall low level of affordability) is caused by out-of-control environmental laws. The group is now suing the State of California for pursuing “racist” climate policies that they claim primarily displace people of color by driving up basic living expenses.

They have a website, some prominent civil rights advocates that have joined them, and a professional video to make the case that California’s housing production is stymied solely due to environmental review under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). Specifically, they allege that the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions under the state’s climate “scoping plan” is exacerbating environmental review by saddling new housing projects with requirements to reduce on-site energy usage and vehicles miles traveled. (They also blame high electricity costs for making the state unaffordable, as a result of mandates to procure more renewables and reduce on-site energy usage, even though these policies are enacted under separate statutes from the state’s climate law.)

Does this lawsuit have merit? No, but the group has correctly identified a major problem in California: the state is unaffordable for too many residents, almost exclusively due to high housing costs resulting from a decades-long history of under-building homes relative to job and population growth.

But the problem with their lawsuit is that they are blaming the wrong policies and decision-makers. Instead of starting by identifying what actions most constrain housing growth and affordability in the state, and then asking how the state is addressing or exacerbating these barriers, the lawsuit assumes (without evidence) that CEQA is the prime barrier to housing.

But study after study has debunked the idea that CEQA lawsuits are a major factor impeding new housing. Instead, the real culprit is restrictive local zoning and burdensome permitting processes.

So why isn’t the group suing every NIMBY-captured local government in the state for preventing housing, which drives up costs and forces long commutes? First, they probably don’t have a great legal cause of action against all these cities — or a convenient way to sue hundreds of them — whereas they can go after a state agency like the California Air Resources Board (CARB) more easily in court. Second, given their industry-backed leadership, I suspect that they don’t really care about local barriers to housing. Instead, they are exercising a longstanding beef against CEQA for its role in slowing megaprojects, especially sprawl development.

Yet the lawsuit is worth keeping an eye on, given the savvy of the industry lawyers behind it and the underlying truth of the problem they’ve identified, if not the remedy to address it.

For more information, you can watch their full anti-CEQA video here, complete with multiple Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. references:

Most Americans probably think of state-sponsored racial segregation in this country in terms of Jim Crow-era segregated water fountains and schools, among other examples, which the Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional in 1954. But when it comes to residential segregation — communities that tend to be exclusively white, Latino, or African American, for example — many Americans might instead think like Chief Justice John Roberts, who described this type of segregation as de facto and not de jure (i.e. a function of official state policies). (Roberts used these terms in the 2007 Supreme Court case addressing two combined challenges to school integration policies, Meredith v. Jefferson County Board of Education & Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1).

The assumption that Roberts and others might have is that this segregation is the result of such factors as discriminatory lending practices or racist realtors, or perhaps through voluntary segregation by members of racial groups seeking to live amongst themselves. In short, anything but state action.

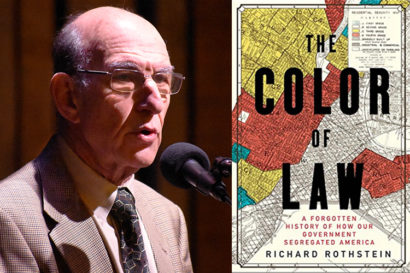

But Richard Rothstein, author of the landmark book The Color of Law, documents how residential segregation in America is not just the result of these de facto policies carried about by non-state actors.

As he described in a recent UC Berkeley podcast (transcript here), this segregation was instead deliberately fostered through government housing policies at the federal level, which led to post-World War II segregated suburbs across the country, including the San Francisco Bay Area and Los Angeles, among other California cities.

It’s worth listening (or reading the full transcript) for Rothstein’s description of this shameful and far-too-ignored history, the effects of which determine so much of the racial, economic and political landscape of the United States to this day.

California’s massive housing shortage relative to population and job growth is only getting worse, and the state’s senate will be examining the issue today at a joint hearing of the Housing and Governance & Finance committees at 1:30pm in the Capitol. I’ll be testifying regarding the link between housing and greenhouse gas emissions.

The hearing comes as the San Francisco Chronicle ran a front page story this morning on the vast number of bills introduced this session to address the crisis. Most of the bills are aimed at high-cost, low-growth, job-rich areas, which are predominantly white and high income, filled with vocal residents who don’t want new growth in their exclusive communities.

Yet if California is to have any hope of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by decreasing driving miles, not to mention addressing the extreme segregation and economic inequality, the state will have to intervene in the face of these restrictive local land use policies.

You can tune in to the hearing and watch live here

California ushered in a whole new way of evaluating the impacts of new projects on our transportation systems when the legislature passed SB 743 (Steinberg, 2013). The implementing guidelines are finally complete, and lead agencies will now be responsible for switching from an “auto delay” metric under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) to one that measures the impacts on overall driving miles (VMT).

To discuss the implementation process, Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) is co-hosting a conference with Portland State University this Friday, March 1st, in Downtown Los Angeles from 8:45 to 6pm. In-person tickets are now sold out, but you can register to view it on line or watch as a webinar afterwards. The agenda is here.

Speakers include Sacramento mayor and SB 743 author Darrell Steinberg (via video), officials from the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research, local leaders implementing innovative VMT mitigation plans, and other experts.

We’ll also discuss our recent CLEE report “Implementing SB 743” on the legal options for creating VMT mitigation “banks” or exchanges. Hope to see you there or that you can tune in live!