Bay Area legislators State Senator Scott Wiener (San Francisco) and Assemblywoman Buffy Wicks (Berkeley) will discuss housing legislation with me tonight on City Visions at 7pm, on 91.7 FM KALW in San Francisco.

Governor Newsom wants 3.5 million new homes built by 2025. How are our legislators planning to get us there? We’ll discuss Senator Wiener’s revamped Senate Bill 50, which encourages development around transit and job centers. And we’ll also find out Assemblywoman Wicks’ plans for this year, after she introduced a suite of housing legislation last year.

Tune in and ask your questions at 866-798-TALK! We’ll be streaming live at 7pm.

As the debate over SB 50 and other state legislative efforts to boost California’s housing supply heats up, it’s worth reviewing some of the data about how dire the housing situation is in the state. Here are some tidbits:

High Home Prices and Rents:

- According to the California Legislature’s Legislative Analysts Office, the average California home costs about two-and-a-half times the average national home price, at $440,000 (and much higher in major metro areas). This price divergence began in the 1970s, when California home prices went from 30 percent above U.S. levels in 1970 to more than 80 percent higher by 1980.

- Per the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD), the majority of California renters (more than 3 million households) pay more than 30 percent of their income toward rent, while nearly one-third (more than 1.5 million households) pay more than 50 percent of their income toward rent.

- Per a Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice study, 19% of community college students in California are homeless, while 60% are considered “housing insecure.”

- Almost one-quarter of all homeless people in the country live in California, according to federal data.

Extreme Housing Shortage Relative to Demand:

- California ranks 49th among all U.S. states in housing units per resident, behind only Utah, where residents tend to have large families in single homes, per a 2016 McKinsey study. The McKinsey analysis showed that California has 358 homes per 1,000 people, whiles comparable states like New York and New Jersey have more than 400 homes per 1,000 residents.

- HCD calculated that the state needs to build 180,000 additional homes annually, but over the last ten years housing production has averaged fewer than 80,000 new homes each year (and is currently declining).

Local Zoning is a Key Barrier:

- While the 2016 McKinsey study presented a goal of 3.5 million units needed to address the shortage and stabilize prices, UCLA’s Lewis Center found that California cities and counties currently only zone for a combined 2.8 million new housing units. And many of these zoned parcels are located in rural areas far from jobs, which is not where housing is needed.

- The New York Times recently mapped the local zoning in some major cities and found that 75 percent of Los Angeles and 94 percent of San Jose is zoned exclusively for single-family homes.

- UC Berkeley’s Terner Center documented via a statewide survey of local governments that in two-thirds of California’s cities and counties, multifamily housing (i.e. apartments) is allowed only on less than 25 percent of the available land.

- The Terner Center similarly showed that fully one-half to two-thirds of all land in California is reserved exclusively for single family homes.

- In 1933, according to University of Texas’s Andrew Whittemore, less than 5 percent of Los Angeles’ zoned land was restricted exclusively restricted for single-family homes. By 1970 though, half of the land in Los Angeles was zoned only for single family residences, per UCLA’s Greg Morrow.

- Morrow noted that zoning in Los Angeles went from allowing up to 10 million residents in 1960 to 3.9 million residents by 1990.

Local Permitting Processes Remain a Major Barrier:

- The Terner Center estimated that local permit and impact fees on new units average $150,000 per unit.

- Environmental review under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), triggered when local governments make permitting decisions discretionary as opposed to ministerial, ranked as the ninth biggest barrier to housing overall, according to the Terner Center survey of planners.

- The Rose Foundation found that CEQA litigation affects fewer than 1 out of 100 projects not already exempt from the law, while litigation has been steady at about 195 lawsuits per year on average since 2002.

These numbers on California’s housing crisis show not only the human cost of the shortage, but the need for a strong policy response to fix the governance system that exacerbates the problem. We’ll see if this legislative session brings any change.

The UN climate conference in Madrid last month may have ended poorly, but conference attendees had a big success story right in front of them. Spain’s success achieving efficient – and enjoyable – land use and transportation outcomes is a model other countries and states should emulate to address climate change.

Spanish cities and towns feature many remarkable urban spaces, not unlike those found in other European countries. These areas tend to prioritize compact apartments located within walking distance of abundant transit, shops, bike lanes and jobs, with many containing pre-automobile-era narrow cobblestone streets built for people and not vehicles. Cities are often built around plazas, typically along with town halls and churches. They also protect against sprawl by prioritizing open space and agricultural land, particularly in the central and southern part of the country. Meanwhile, a high speed rail network connects most of the country’s major urban areas.

The result? While many factors probably come into play, US News in 2019 ranked Spain tops among all countries in terms of the overall happiness of its citizens. The country also ranked 18th in overall quality of life and among the top in food and culture.

You can see this effect on the ground. Spanish cities and towns are among the most walkable and enjoyable cities I’ve experienced. Particularly in the capital city of Madrid, where the UN conference was held, residents can access most destinations by transit or on foot, and the central city is closed to vehicles not registered to central city residents, while any other entering vehicle must meet low- or zero-emission standards. As a result, the Madrid city center is a quiet and clean pedestrian playground. And this same dynamic is present in cities and towns throughout the country, based on my travels there. It’s likely a major reason for the country’s success in terms of emotional well being.

This urban walkability has positive environmental effects, too, particularly on greenhouse gases. According to World Bank figures, Spain’s per capita carbon emissions is 5 metric tons, ranking it approximately 60th on the list of 192 countries, despite having a GDP per capita that ranks roughly 30th. These emission figures stand in stark contrast to the 16.5 metric tons of emissions for the average United States resident, more than 3 times as much as the average Spaniard. And even similarly developed and urban countries like Japan and Germany have almost twice the emissions per capita of the Spanish, with 9.5 per Japanese resident and 8.9 per the average German.

To be sure, some of this climate progress is due to their increasingly clean electricity grid, which has seen a significant deployment of renewables over the past decade. But smaller homes and walkability that decreases driving miles helps, too. For example, overall driving miles (or kilometers, in this case) in the country is relatively low for a developed nation, at approximately 400 billion per year. With 47 million residents in Spain, that equals roughly 8,500 km per person, or 5,287 miles per year (14.5 miles per day per person). By contrast, according to the Eno Center, the average Californian drives 50% more miles than the average Spaniard, at 8,728 miles per year, or 24 miles per day (rural states do even worse, with Wyoming at a whopping 16,900 miles per year, or 46 miles per day per person).

The lessons learned? Policy makers should design towns to maximize walkability and transit access, limit private vehicles, prioritize public spaces like plazas, and preserve surrounding farmland and open space from sprawl. Hopefully attendees at the UN Climate Conference experienced some of these Spanish practices on land use and transportation firsthand. Because the climate-friendly results mean cleaner and happier living overall, something worth achieving everywhere.

California State Senator Scott Wiener launched his third legislative attempt today at boosting California’s housing supply. SB 50 aims to address the state’s massive housing shortage, which has resulted in high home prices and rents, gentrification, displacement, inequality, homelessness, and a mass middle-class exodus to high-emission states like Texas and Arizona.

Because this housing undersupply is caused primarily by restrictive local land use policies in the state’s coastal job centers, Wiener’s approach has been to require cities and counties to allow apartment buildings near major transit centers. His first attempt in 2018 (SB 827) died quickly in committee. His second attempt last year (the birth of SB 50) was unilaterally shelved for a year by State Senator Anthony Portantino, who represents the affluent Southern California city La Cañada Flintridge (that city quickly became a poster child to housing advocates for high income single-family homeowners who don’t want to allow new residents in apartments into their neighborhoods).

The clock is now ticking on SB 50 in 2020. Under legislative rules, the bill must pass the full Senate by the end of this month — and first make it out of Sen. Portantino’s committee.

So Sen. Wiener is trying again, unveiling at an Oakland press conference this morning a critical amendment to delay statewide implementation for two years in order to give local governments the opportunity to develop their own plans that meet or exceed the housing, equity and environmental goals of SB 50. Otherwise, SB 50’s provisions relaxing height, parking and density requirements around major transit stations will automatically prevail.

Specifically, the state (through the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research) will develop guidance for these “local flexibility plans” by mid-2021. Cities and counties must then submit their plans for approval to the California’s Department of Housing and Community Development. That agency will then certify that the local plans are as stringent as SB 50. The local plans must be in place by January 1, 2023 in order to avoid defaulting to SB 50 statewide standards.

Otherwise, the substance of the bill remains essentially unchanged from last spring (here’s my rundown on the last changes before Sen. Portantino shelved it).

These new amendments seek to mollify critics who complained that the statewide approach undercuts local flexibility to meet the targets in a more tailored way. For example, rather than having uniform four-story apartment buildings around a major transit stop, perhaps a city would prefer to meet the overall housing production goals with a taller building in one spot and a shorter building across the street.

Will these changes be enough to satisfy local government objections? Probably not in many cases. The objections are less about local control and more about visceral dislike for apartment buildings and the residents they may bring. Arguments about local control — and relatedly against market-rate housing and instead building only subsidized affordable units — are often not made in good faith. Critics quickly move the goal posts as soon as amendments are made in their direction.

Take for example Sen. Portantino’s initial reaction to these amendments, complaining about not enough affordable housing, per his spokesperson to the San Francisco Chronicle:

“It was the senator’s hope that by taking a breath with SB50 it would focus efforts on actually building affordable housing as opposed to the market-rate housing predominant with SB50.”

This comment ignores that SB 50-type reform would result in the biggest boost to subsidized affordable units in the state’s history, at possibly a seven-fold increase. All without raising taxes or issuing bonds, and without delay about where to build these units even if public funds are available.

Still, these amendments may persuade critics who are on the fence. And perhaps most critically: will Governor Newsom now throw his weight behind the measure to help it pass? This is a big test for the governor on one of his signature campaign issues.

All in all, the next few weeks will be instructive as to whether or not California leadership can meaningfully address the the housing shortage and its severe equity, economic and environmental consequences.

The California Preservation Foundation is hosting a webinar debate today from 11am to noon on the housing shortage, entitled “Point-Counterpoint: Streamlining Housing Development vs Local Control.” I’ll be on the pro-housing side against a few prominent “local control” anti-housing advocates.

Moderated by Diane Kane, PhD (Emeritus Trustee at the California Preservation Foundation), the panelist debaters include:

- Barbara Bry, City Councilmember, City of San Diego

- Todd David, Executive Director, San Francisco Housing Action Coalition

- Ethan Elkind, Director, Climate Program, Center for Law, Energy & the Environment, U.C. Berkeley

- Dennis Richards, Planning Commissioner, City of San Francisco

The questions will cover issues like CEQA’s effect on housing production, NIMBY motivation, how historic preservation affects the shortage, and if single-family homes are inherently a ‘bad’ thing.

You can register here (registration is $40 for members and $60 for non-members) to join the webinar and ask your questions of the panelists.

How has the city of San Francisco changed in the last decade, and what will it look like in the future? On tonight’s City Vision, I’ll host John Rahaim, Planning Director for the City and County of San Francisco, to discuss these questions.

In his 12 years leading the Planning Department, John has tackled issues ranging from the housing shortage to sea level rise. How have politics and environmental regulations impacted urban development in San Francisco? And how is the city managing growth while addressing climate change, transportation infrastructure, and racial equity?

Tune in at 7pm tonight or stream live. You can join the conversation by calling 866-798-TALK or e-mail or text us at cityvisions@kalw.org. You can also reach us by tweeting us at @cityvisionskalw.

In response to the state’s severe housing shortage, California legislators have been quietly strengthening its housing mandate process for local governments. I’ll discuss the new policies and what the future will bring on a webinar today at noon with outgoing California Department of Housing and Community Development director Ben Metcalf.

Metcalf’s agency takes the lead in assigning housing goals to each region of the state. Those regional entities in turn assign housing allocation numbers to local governments in the jurisdiction, which must plan for this new housing in four-year cycles.

Until recently, the process was easily gamed by local governments, with no penalties for non-compliance. But legislators have now added significant enforcement powers.

As examples of this beefed-up process, the state now requires streamlined local approval for housing projects in jurisdictions that are not producing enough housing according to these mandates. The state has also been linking transportation funding to local compliance. And perhaps most prominently, Governor Newsom is suing local governments like Huntington Beach for its inaction.

To learn more, you can register this morning for the noon-1pm webinar, which is co-sponsored by the California Lawyers Association and the Council of Infill Builders. MCLE credit is available for attorneys, and registration is free for members of the Council of Infill Builders. Hope you can join!

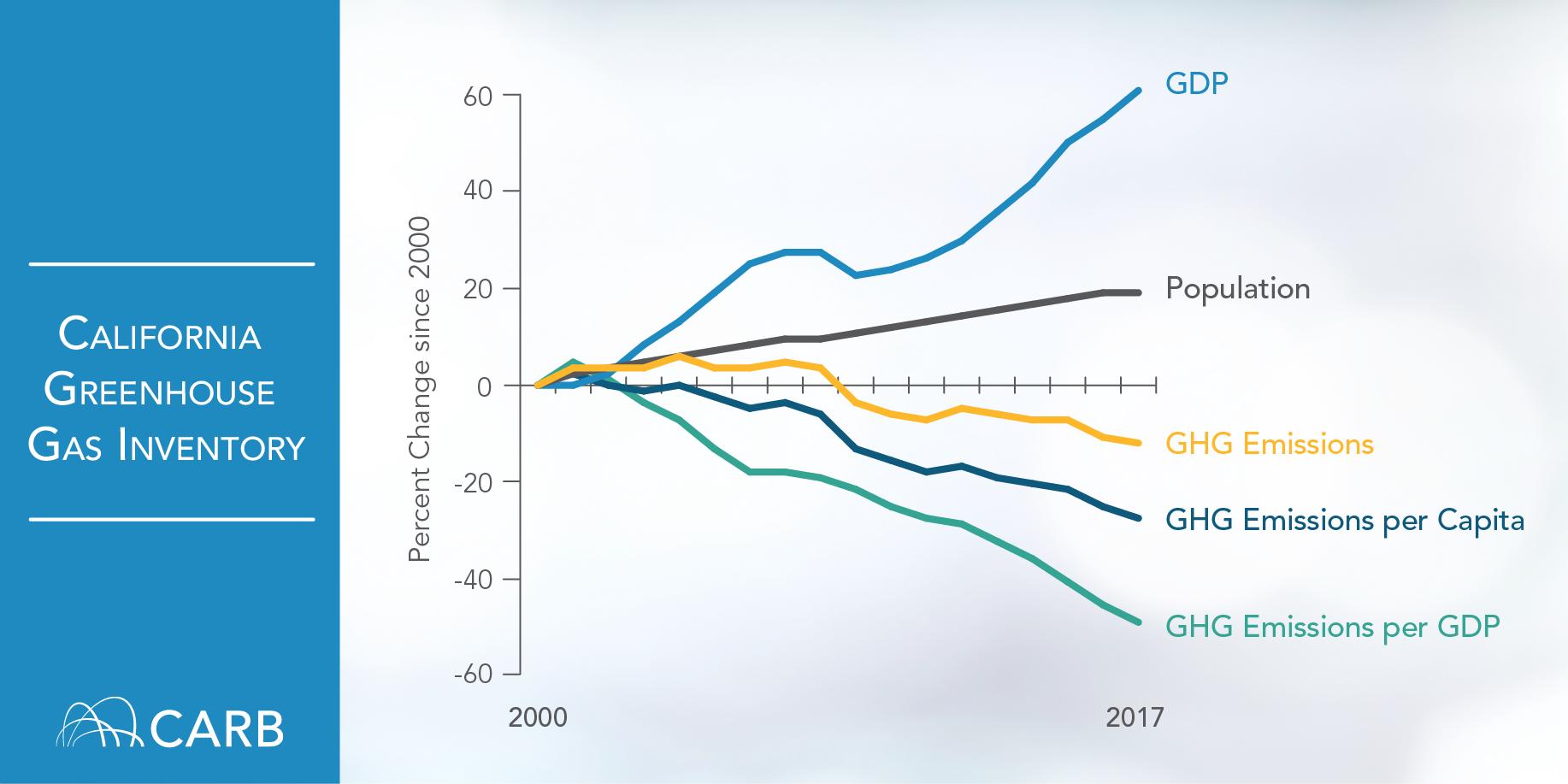

Good news on California’s efforts to fight climate change: in-state emissions in 2017 (the latest available data) were down over 2016 and ahead of the state’s mandatory 2020 goals. The California Air Resources Board announced the progress yesterday, with this chart showing emissions in context of population and GDP:

Overall, emissions totaled 424 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2017, down 5 million metric tons from 2016. For reference, the 2020 reduction target is 431 million metric tons.

Most of the progress came from the electricity sector, where for the first time renewable sources made up a larger percentage of the generation than fossil fuels.

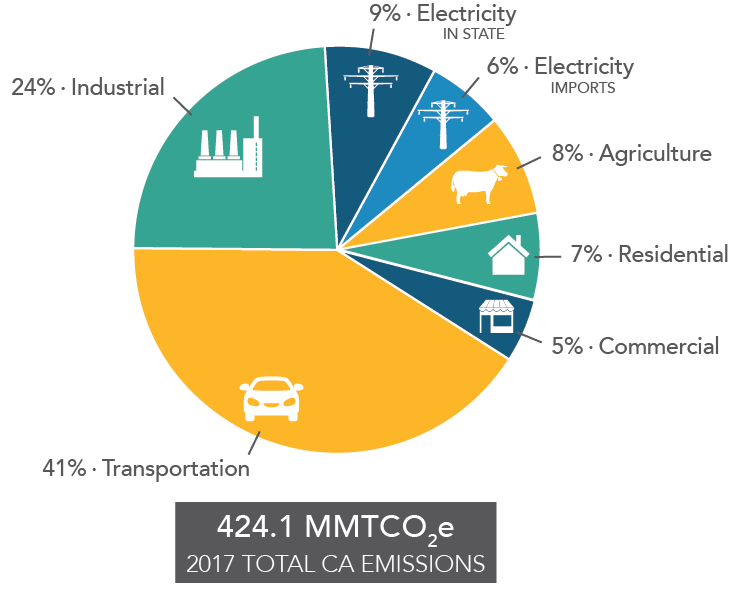

However, transportation emissions increased 0.7% in 2017, compared to a 2% increase in 2016, mostly from passenger vehicles. That total is even worse when you consider pollution from oil and gas refineries that make the fuel for these passenger vehicles. Together with hydrogen production, these sources constituted one-third of the state’s total industrial pollution.

Here’s the latest pie chart on where the emissions came from in 2017:

While the story is overall positive for California’s climate efforts, the state will have to redouble its efforts to reduce driving miles by allowing more homes to be built near jobs and transit, while transitioning the remaining driving miles to zero-emission technologies like electric vehicles.

Building anything in California near transit stops is hard enough, but many affordable housing advocates argue that we should only build subsidized homes for low-income residents — and not market-rate homes for higher-income people. They cite evidence that low-income people are much more likely to actually ride the transit where they’ll live, as opposed to high-income people who will still drive.

It’s true that we should build as much affordable housing (and offices) near transit as we can to boost ridership. But we should also allow market-rate development near transit, too, for similar environmental reasons.

Yes, high-income people near transit probably won’t actually use the transit that much. But they will on balance drive significantly fewer miles than if they lived in sprawl areas. And fewer driving miles means less pollution and fewer greenhouse gas emissions.

Ironically, the evidence for this environmental benefit comes from a study meant to document how important it is for low-income residents to live near transit. The nonprofits TransForm and California Housing Partnership Corporation released a study [PDF] in May 2014, based on Caltrans’ California Household Travel Survey (CHTS), arguing explicitly for affordable housing near transit. In fact, they used the data to argue against locating higher-income housing near transit, pointing out that higher-income households drive more than twice as many miles and own more than twice as many vehicles as low-income households living within 1/4 mile of frequent transit.

But the data actually revealed something more important: higher-income residents near transit drove almost 30 miles fewer per day than similarly situated people in sprawl areas. By comparison, low-income residents only drove about 20 miles fewer per day, compared to similar income sprawl residents. Check out this chart that summarizes those results:

So while I agree we want to locate low-income residents near transit, we also need high-income people living in cities near transit. Otherwise, the increased driving miles will mean more traffic, pollution and unattainable climate goals.

California Governor Gavin Newsom campaigned on solving the state’s infamous housing affordability woes. In 2017, he promised 3.5 million housing units by 2025, or 500,000 per year. This boost in supply would serve to stabilize prices and relieve the crushing burden that housing costs create for working and low-income residents.

But with the legislative tabling last week of SB 50, the only bill in the legislature to upzone neighborhoods near transit and jobs, that goal now appears to be infeasible. Gov. Newsom’s signature issue is already looking to be a failure.

Why? California is currently zoned for 2.8 million units, as UCLA Luskin comprehensively documented. And many of those planned units are in areas not in need of new housing, such as in rural, fire-prone parts of the state with low demand. Furthermore, as the study authors point out, the planned units may face other obstacles to getting built, such as permitting challenges. In short, massive upzoning is required to meet the Governor’s goals.

Sure, it’s only a few months into Gov. Newsom’s term, so couldn’t solutions emerge later? Here’s the problem: by tabling this effort into an election year (2020), legislative appetite to address the fundamental cause of the problem (resistance from affluent, predominantly white suburbs) will wane further. And even if the legislature acts in future years, it will still take years for the changes on the ground to take hold, as communities likely resist these zoning changes by enacting more permitting obstacles. At that point, the 2025 goal will be out of reach. The state needs to start the solutions now.

Interim steps certainly exist, such as strengthening the affordable housing allocations the state gives to local governments. But with at least a 700,000 zoning shortfall statewide to get to 3.5 million units, those steps will hardly make a dent.

So far, the Governor has not wanted to take an aggressive stance to save upzoning measures like SB 50. As Liam Dillon of the Los Angeles Times reported on the shelving of SB 50, Newsom stated the following yesterday:

“To the extent that we can find a pathway to take core components of SB 50 and getting it over the finish line, I’m committed to helping support that effort,” Newsom said.

But Gov. Newsom apparently did not step in to shepherd SB 50 in the state senate, as Gov. Brown did in 2017 to extend the cap-and-trade program in the face of legislative resistance.

There is still time, and credit is certainly due to Newsom for championing this issue (Gov. Brown, by contrast, viewed the politics as too intractable to try very hard). But the crisis is real, and words are not enough. Action, leadership, and courage are required, and the window of opportunity for real solutions may soon be closing.