Hawaii’s energy and land use challenges are very much a postcard from the future for mainland USA. I’ve written before about how renewables and EVs in Hawaii are trend-setting for the rest of the country. But it’s true on land use, too.

Native Hawaiians are allotted homesteads on lands that were property of the dethroned Hawaiian crown. Yet many Native Hawaiian have waited years to be able secure lands and affordable homes. Now pre-fabricated, tiny homes may offer the solution, thanks to financing from the nonprofit Council for Native Hawaiian Advancement. Hawaii News Now covered the story recently:

Hawaii News Now – KGMB and KHNL

Why is this useful for the mainland? Here in California, high construction costs are part of the reason for our housing shortage. Prefabricated homes, like those in Hawaii, represent a promising way to bring down the costs and ensure more affordable and ample homes for everyone.

We’ve already seen the movement start to take hold, such as tiny apartments in San Francisco and Sacramento. And prominent developers like the Bay Area’s Rick Holliday have begun building modular homes for the likes of companies like Facebook, all to bring down construction costs but still deliver high-quality homes.

If it can work in Hawaii, it can certainly work across the country.

Malcolm Gladwell (author and reporter for the New Yorker) has an entertaining and informative podcast focused on the unjust public subsidies for fancy private golf clubs, particularly in Los Angeles. He talks about how much land they take up within the urban landscape that is otherwise starved for public parks.

Perhaps more damning, he discusses at length the tax subsidies these exclusive, wealthy country clubs receive, primarily due to Prop 13. At one point, he estimates that one of these expansive golf courses is sitting on land worth about $9 billion, which would have triggered property taxes of $90 million per year. But under Prop 13, the country club pays $200,000 per year.

An admitted golf-hater, Gladwell would ‘gladly’ see these spaces converted to public use.

My only quibble with his piece is that while urban Los Angeles is park-starved, it actually has a huge amount of open space, from the beach to the nearby mountains. Sure, not everyone has easy means to get to these locations, but they are otherwise transit-accessible and beautiful places that most cities around the country would love to have.

The podcast is definitely worth your time, whether you like golf or not.

Richard Reeves, a U.K. native, takes Americans to task in a New York Times op-ed for pretending that we’re not a classless society. He points out how the wealthy use local housing policies to protect their wealth, advantage their children, and prevent the lower classes from accessing educational and job opportunities:

Richard Reeves, a U.K. native, takes Americans to task in a New York Times op-ed for pretending that we’re not a classless society. He points out how the wealthy use local housing policies to protect their wealth, advantage their children, and prevent the lower classes from accessing educational and job opportunities:

Things turn ugly, however, when the upper middle class starts to rig markets in its own favor, to the detriment of others. Take housing, perhaps the most significant example. Exclusionary zoning practices allow the upper middle class to live in enclaves. Gated communities, in effect, even if the gates are not visible. Since schools typically draw from their surrounding area, the physical separation of upper-middle-class neighborhoods is replicated in the classroom. Good schools make the area more desirable, further inflating the value of our houses. The federal tax system gives us a handout, through the mortgage-interest deduction, to help us purchase these pricey homes. For the upper middle classes, regardless of their professed political preferences, zoning, wealth, tax deductions and educational opportunity reinforce one another in a virtuous cycle.

It takes a brave politician to question the privileges enjoyed by the upper middle class. Recently, there have been failed attempts to make zoning laws more inclusive in supposedly liberal cities like Seattle and states like California and Massachusetts. The handout on mortgage interest appears to be an indestructible deduction (unlike in Britain, where the equivalent tax break was phased out under both Conservative and Labour governments by 2000).

Considering that zoning was essentially invented as a tool for racial exclusion and white supremacy back in the 1920s, Reeves’ argument is pretty damning. As America’s income inequality worsens, local housing policies that prevent new multifamily developments only exacerbate the problem, from a moral, economic and environmental standpoint.

Perhaps a metaphor for their approach to innovation, Apple is fully embracing the sprawl office model of the past, while Google embraces the future with talks to build a downtown San Jose campus near rail.

The Apple “donut” campus (photo right), set to open soon in Cupertino, is a giant parking lot with an office building on top, no matter how many solar panels and EV charging stations the company boasts about adding. It was Steve Jobs’ last vanity project, and at heart it’s firmly of the decade he was born — the auto-oriented suburban office campus of the 1950s.

Meanwhile, Google looks to be following other advanced tech companies, like Amazon, LinkedIn, and Salesforce, by exploring options for a high-rise, infill mixed-use office right next to the future high speed rail stop and current Amtrak and Caltrain depot in downtown San Jose.

Silicon Valley is an an absolute housing and traffic crunch, due to those cities’ willingness to permit office sprawl but no accompanying housing. The choice by Apple will only reinforce that failed dynamic, while Google’s efforts show that the worker of tomorrow does not want to repeat the insanity.

Jennifer Hernandez of the law firm Holland & Knight and John Gamboa of the Greenlining Institute criticized our recent UC Berkeley report on 2030 housing scenarios for California that could help meet the state’s long-term greenhouse gas goals.

Jennifer Hernandez of the law firm Holland & Knight and John Gamboa of the Greenlining Institute criticized our recent UC Berkeley report on 2030 housing scenarios for California that could help meet the state’s long-term greenhouse gas goals.

Their piece in the Fox & Hounds website makes the hard-to-argue-with point that California policy makers should design climate policies — and particularly cap-and-trade — with an eye toward the costs on average Californians.

From my perspective, the state is already moving in that direction, with detailed assessments of the impacts of these programs on everything from gas prices to electricity rates. The state is also mitigating the impact for residents, with “climate credits” on our electricity bills, a guaranteed set-aside of cap-and-trade auction revenue for disadvantaged communities, and greater electric vehicle rebates for low-income residents, among other efforts.

But sure, more could be done, and it’s smart to examine these policies critically. Certainly from a pure political perspective, California’s climate efforts won’t retain support if they cause price and other shocks to residents.

So I’m all with Hernandez and Gamboa on the general point, although I think they fail to acknowledge how much care and analysis the state has already put into the programs involved.

But then the article singles out “Right Type, Right Place” report for criticism for being obtuse on the impacts of climate-friendly housing on everyday Californians:

In one recent report, for example, some of the most respected housing policy thinkers in the state make the case that if California could only build more high-density housing in a narrow subset of urban areas along the coast—where transit is already in place—greenhouse gas emissions from cars could be reduced by nearly two million metric tons per year, household utility bills trimmed by $5 a month, and monthly transportation costs lowered by $58. All while requiring people to spend only $38 more per month on rent—and less than $14,000 more for an average home.

Where do we sign up, right? What the study, like so many others, fails to account for is the social cost—and the economic unlikelihood—of this “infill-only” scenario actually coming to pass. The authors’ housing cost data doesn’t factor in the cost, for example, of relocating hundreds of thousands of people already living in existing lower-cost, lower-density homes in these areas. The study doesn’t account for the fast-growing fees many coastal jurisdictions are imposing to slow this very type of housing (as much as $100,000 per unit in some places). Nor does it account for the stark differences in the cost of land, which is between three and 10 times higher in coastal areas than inland California (and which is the biggest reason so many workers slog through three-hour commutes each day).

Most importantly, the study seems to accept the fact that this “preferred,” coastal-focused housing scenario will produce an average monthly rent of $2,702. Even without factoring in massive displacement, rising local exactions, and land costs that are likely to push development elsewhere, this number alone should give everyone pause. To pay that much rent, an “average” household would need to earn $97,200 a year! The median income in California today is only $62,000.

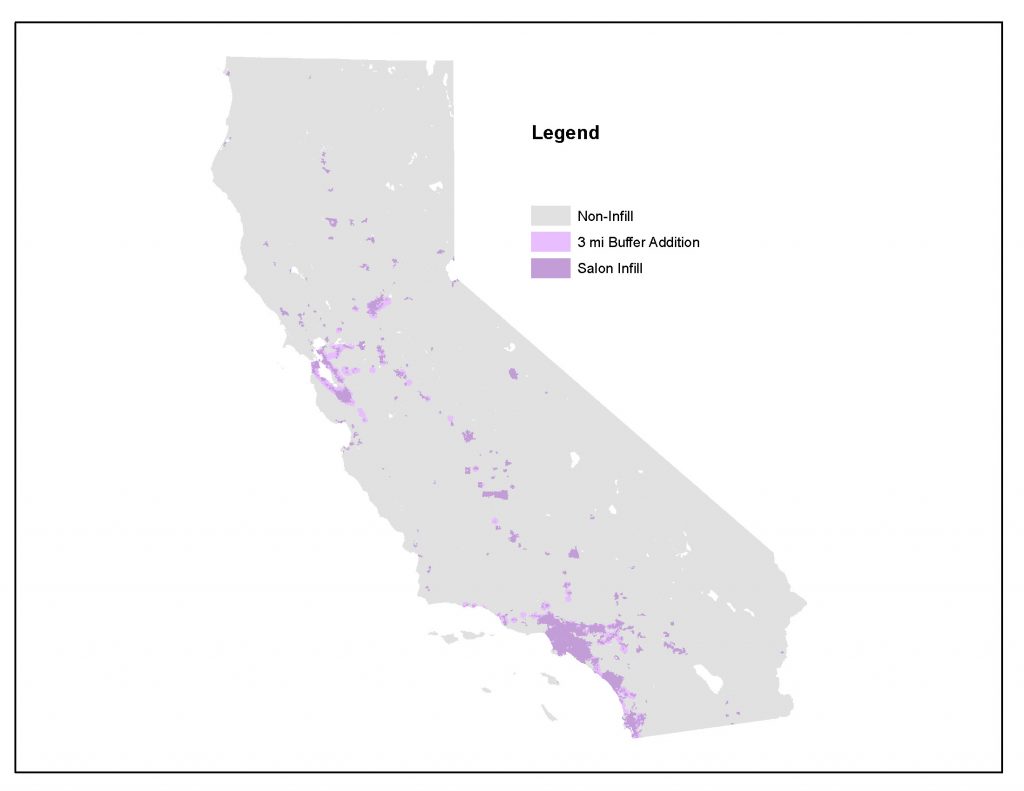

First, let’s look at the claim that our study limited development in the infill scenario to just a “narrow subset of urban areas along the coast.” One look at the map below of “purple” infill areas should dispel that characterization:

Sure, some of the purple areas are near the coast, but so is the vast majority of California’s population. This map shows that there’s actually a lot of land that could meet the preferred criteria all around the state.

Second, while it’s true our report methodology didn’t include a way to measure “social costs,” our policy recommendations addressed concerns around gentrification and displacement from infill development. And we offered ways to mitigate those impacts.

Third, the policy recommendations in the report also addressed the need to remove local barriers to housing in prime infill areas, such as the escalating fees on urban development that Hernandez and Gamboa mentioned.

Finally, Hernandez and Gamboa’s effort to compare the average rent in our infill scenario to median household income seems less important than comparing that rent amount to what Californians are actually paying today, when you combine average current household and transportation costs. That would be a more interesting comparison.

I should also note that if California actually succeeded in building enough housing to meet population growth, as our scenario assumed but as is not happening in reality, my personal view is that the extra housing supply would stabilize prices and rents in these infill areas (although we didn’t model that effect in our report).

As a general response to this criticism, our report did not do a financial feasibility analysis of the scenarios, so I think critiques related to that lack of information are valid. But we were up front about missing that level of analysis and recommend that future research build on this work. After all, this is the first comprehensive, academic effort to look at 2030 housing scenarios and how they can fit with the state’s greenhouse gas reduction goals. This report is an important starting point for this discussion, and we hope others build on it.

But it’s not accurate to suggest we didn’t think about these “social” and other economic costs. And this criticism also misses the added benefit of more infill housing for low-income residents which we also didn’t quantify: access to high-paying jobs in cheaper overall housing. Right now, with lower-cost housing out in sprawl areas, these residents not only face long commutes at high cost to access good jobs, they’re contributing to environmental degradation for everyone.

Solving that problem would be an environmental and economic win-win for all of California’s residents. And in any back-and-forth over details, we should not lose sight of that larger, more important point.

With so much noise coming out of Washington DC these days, from phony bill signing ceremonies to endless provocative tweets and misinformation, it’s easy to lose sight of the real, consequential policy battles going on at the moment.

On the environment, the big battle in Congress will take place over the budget late this summer. A temporary stopgap measure helped preserve funding for key environmental initiatives, such as clean energy research and transit projects like Caltrain electrification. But that bill just kicked the can down the road to September, when the government must act to avoid a shutdown.

The Trump administration’s proposed budget would zero out basically all environmental programs, including all new transit projects. I’m following the fate of clean energy research at the uber-successful ARPA-E in particular, at the Department of Energy:

September is now the new showdown date for the future of federally-funded breakthrough energy research in the United States. And if Trump has his say, the September fight could be waged in a higher-stakes, post-filibuster, 51-votes-to-pass-a-bill Senate. (Regardless, apparently, of any consequences for Republicans when Democrats next control the White House and/or Congress.)

On transit, the administration wants to end all federal support for urban transit projects, essentially ending a half-century of federal involvement in this area. As Transportation for America writes:

The administration reiterates their belief that transit is just a minor, local concern.

“Future investments in new transit projects would be funded by the localities that use and benefit from these localized projects,” they write, making it clear that they see no benefit in providing grants to cities of all sizes to build new bus rapid transit or rail lines, or expand existing, well-used lines so they can carry more passengers.

The administration even uses the example of local cities approving their own funding measures for transit as a reason to discontinue federal support, when those local measures were actually sold as ways to leverage federal dollars in this longstanding partnership.

The good news is that many of these programs and initiatives have bipartisan support. We saw that in action with the stopgap measure passed this spring. But that support will be put to the test as we witness an assault on federal dollars for the environment and public health like we’ve never seen before.

Perhaps no other local land use issue can be as important — and detrimental — to quality of life, convenience, and the environment as parking. High local parking requirements for new development drive up home prices and rents, induce more traffic, and waste space. And poor parking management of existing spaces leads to more air pollution and congestion.

Yet too often failed parking policies soldier on, based on zombie regulations from outdated planning guidelines and the fear of making destinations inconvenient to access by private cars. It’s particularly a waste in transit-oriented, infill neighborhoods where convenient alternatives to driving exist.

With that in mind, I was pleased to co-author an op-ed in today’s Los Angeles Times with Mott Smith, director of the nonprofit Council of Infill Builders. The organization just released a new report Wasted Spaces: Options to Reform Parking Policy in Los Angeles at Los Angeles City Hall a few weeks ago, and the op-ed contains recommendations based on that publication.

The issue of parking policy reform is particularly acute in Los Angeles, where 14% of the county — over 200 square miles — is now dedicated to parking. After over a half-century accommodating the automobile at all costs, the region now has 18.6 million spaces for 3.5 million housing units, or 3.3 spaces per vehicle.

To bring reform, Mott and I argue in the piece that:

Local leaders should prioritize urgent reform of L.A.’s parking policies, particularly in transit-oriented neighborhoods, with the following measures:

-

Eliminate or reduce parking requirements for any new development projects.

-

Ensure that revenue from parking benefits the local community.

-

Rather than mandate new parking requirements in the zoning code, promote shared parking and alternative transportation options.

Local leaders should start these reforms now, or risk continuing the failed legacy that has been so stifling for mobility, affordability, and air quality in the region.

One of the frustrating aspects of arguing with those who oppose new housing in their neighborhood is the typical dodge-and-weave around Econ 101 issues. As any first-year econ student will tell you, more supply of housing will lower prices. But many NIMBYs instead argue that more housing just drives up prices by gentrifying neighborhoods, when the exact opposite is true.

One of the frustrating aspects of arguing with those who oppose new housing in their neighborhood is the typical dodge-and-weave around Econ 101 issues. As any first-year econ student will tell you, more supply of housing will lower prices. But many NIMBYs instead argue that more housing just drives up prices by gentrifying neighborhoods, when the exact opposite is true.1. Econ 101 supply-and-demand theory is helpful in discussing these issues, but don’t rely on it exclusively. Instead, use a mix of data, simple theory, thought experiments, and references to more complex theories.2. Always remind people that the price of an apartment is not fixed, and doesn’t come built into its walls and floors.3. Remind NIMBYs to think about the effect of new housing on whole regions, states, and the country itself, instead of just on one city or one neighborhood. If NIMBYs say they only care about one city or neighborhood, ask them why.4. Ask NIMBYs what they think would be the result of destroying rich people’s current residences.5. Acknowledge that induced demand is a real thing, and think seriously about how new housing supply within a city changes the location decisions of people not currently living in that city.

6. NIMBYs care about the character of a city, so it’s good to be able to paint a positive, enticing picture of what a city would look and feel like with more development.

Housing scarcity—exacerbated by the ridiculous amount of this city zoned for single-family housing—deserves as much blame for the displacement crisis as gentrification. More. And unlike gentrification (“a once in a lifetime tectonic shift in consumer preferences”), scarcity and single-family zoning are two things we can actually do something about. Rezone huge swaths of the city. Build more units of affordable housing, borrow the social housing model discussed in the Rick Jacobus’ piece I quote from above (“Why We Must Build“), do away with parking requirements, and—yes—let developers develop. (This is the point where someone jumps into comments to point out that I live in a big house on Capitol Hill. It’s true! And my house is worth a lot of money—a lot more than what we paid for it a dozen years ago. But the value of my house is tied to its scarcity. Want to cut the value of my property in half? Great! Join me in calling for a radical rezone of all of Capitol Hill—every single block—for multi-family housing, apartment blocks and towers. That’ll show me!)

Both pieces are worth reading in full, especially for those concerned about the lack of new housing supply in our job- and transit-rich urban centers.

Falling transit ridership is a nationwide problem, but it’s particularly a setback in Los Angeles, which is investing like crazy in transit due to two recently passed transportation sales tax measures. Laura Nelson covered the recent ridership decline in the Los Angeles Times and what L.A. Metro plans to do about:

Metro bus ridership fell 18% in April compared with April 2015. The number of trips taken on Metro buses annually fell by more than 59 million, or 16%, between 2013 and 2016.

A recent survey of more than 2,000 former riders underscores the challenge Metro faces. Many passengers said buses didn’t go where they were going — or, if they did, the bus didn’t come often enough, or stopped running too early, or the trip required multiple transfers. Of those surveyed, 79% now primarily drive alone.

In an attempt to stem the declines, Metro is embarking on a study to “re-imagine” the system’s 170 lines and 15,000 stops, officials said. Researchers will consider how to better serve current riders and how to attract new customers, and will examine factors including demographics, travel patterns and employment centers.

Meanwhile, as Metro explains in its outlet The Source:

Metro has not embarked on such a systemwide effort since the 1990s so it is timely given the significant expansion of the Metro Rail system this century, growth of municipal operator services and the popularity of other transportation options (i.e. ride hailing services such as Lyft and Uber).

As I blogged earlier, it was easy to dismiss prior reports of falling ridership, but now is definitely a good time to take it seriously.

But Metro won’t exactly be hurrying to get to the bottom of this. The bus system review isn’t planned to be completed until April 2019, which will then require public hearings later that year. So any actual changes won’t go into effect until December 2019 — at the earliest.

Two years seems like a really long time to study this issue, although Los Angeles does have an enormous system. Still, a little urgency could be in order. And in the meantime, the agency could focus on one immediate step that is guaranteed to boost ridership: require local governments with major transit stations to relax restrictions on adjacent development.

And Metro could start with the recalcitrant neighborhoods around the new Expo Line.

Otherwise, we’ll have to wait a while on any results from the bus study.

Last month former California assemblyman John T. Knox passed away at 92. He was a progressive Democrat from Contra Costa County in the East Bay who was the driving force behind the 1970 California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). The East Bay Times has more on his life.

His passing is an opportunity for reflection on the state of CEQA, California’s bedrock environmental law. It’s a perennially controversial topic. Big businesses hate it because they get sued under CEQA and have to build in the litigation uncertainty into their projects as a result. Labor unions love it because it gives them leverage to sue non-union project proponents unless they agree to hire unionized workers. And traditional environmentalists and NIMBYs love it because it gives them leverage over basically any proposed project in the state.

As someone who is motivated to address climate change and boost sustainable housing growth in the state, I’m personally mixed on CEQA. I don’t like its negative effects on infill housing, but I like the basic concept and how CEQA applies to environmentally destructive projects, from certain timber harvesting plans to oil and gas exploration.

On the housing front, here are some truths worth acknowledging:

- CEQA is overblown as a reason for the state’s housing shortage. Developers and their advocates like to blame CEQA for the state’s significant undersupply of housing. But the evidence simply isn’t there that it’s a major cause for suppressing production. For example, the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research survey of planners around the state in 2012 indicated that CEQA was not the prime factor in stopping infill, compared to barriers like local zoning, lack of infrastructure, and public antipathy to new development. And the 2016 survey showed that over 40% of cities and counties in California have successfully used CEQA streamlining for infill projects that might have been subject to the law. Meanwhile, a recent report from the Rose Foundation (on which I served as an adviser) put CEQA litigation in context and found it to be rare. Only 195 CEQA lawsuits on average are filed each year in the state, and fewer than 1 out of 100 projects that aren’t already exempt from CEQA are subject to litigation.

- CEQA does kill or maim a lot of important infill housing developments. Despite the overblown nature of the CEQA claims discussed above, there is still plenty of anecdotal evidence that CEQA has taken out some badly-needed infill projects. The law certainly isn’t designed to help promote more infill housing, and one of the negative aspects not discussed in the Rose Foundation report is the defensive project siting and design that CEQA encourages. And that’s why I’d favor far more limited CEQA review for housing in transit-oriented infill areas.

- CEQA is politically very hard to change at the state level right now. The combination of labor union and traditional environmentalist support for CEQA means that wholesale change at the state level is unlikely to happen soon. Rather, progress will be marked incrementally, such as through SB 743, which essentially removes transportation as a CEQA impact for infill projects near transit and simultaneously requires rigorous analysis for outlying sprawl projects.

Knox left this state an important legacy on environmental protection. But just as courts have vastly expanded CEQA’s reach, a new era of housing shortage and climate change mitigation will require updates to the law to address these modern challenges. As we think through policies needed to boost infill housing, policy makers will need to consider options to streamline CEQA further for these priority needs.