Infill development offers many advantages for people: more housing, jobs and retail options closer to transit, so people don’t have to drive long distances; affordable rents and home prices as more housing is built to match demand; and climate and air quality benefits as less driving and paved open space means less pollution.

Infill development offers many advantages for people: more housing, jobs and retail options closer to transit, so people don’t have to drive long distances; affordable rents and home prices as more housing is built to match demand; and climate and air quality benefits as less driving and paved open space means less pollution.

But Hurricane Harvey and the destruction in Houston is now crystallizing another critical benefit of infill: resilience in the face of extreme weather events. As observers have noted, the devastating floods were exacerbated by land use policies that prioritized sprawl over flood control and “green infrastructure” that could have soaked up excess rainwater. More infill development would have saved this open space and avoided building homes that are now essentially destroyed and unlikely to be rebuilt.

Unfortunately, infill development is too often stymied by political barriers — not economic or environmental ones. As Paul Krugman described in an op-ed over the weekend:

In practice, however, policy all too often ends up being captured by interest groups. In sprawling cities, real-estate developers exert outsized influence, and the more these cities sprawl, the more powerful the developers get. In NIMBY cities, soaring prices make affluent homeowners even less willing to let newcomers in.

Krugman compared Houston to San Francisco as two sides of these extremes. Both cities will need infill as a climate resilience strategy: Houston for the flooding we just saw, and San Francisco in the face of sea level rise and more severe droughts (residents in infill developments use less water per capita), among other looming environmental challenges.

So perhaps one bright spot from this tragedy is that infill advocates can now point to Houston as a clear symbol of why infill is also an important adaptation strategy in a world with a rapidly changing climate.

California is on the verge of passing three big bills to address the severe housing shortage, as Rick Frank writes on Legal Planet. Two of the bills will help fund affordable housing and one will streamline local review of projects in cities and counties that haven’t met their regional housing goals, as set by the state and regional agencies.

California is on the verge of passing three big bills to address the severe housing shortage, as Rick Frank writes on Legal Planet. Two of the bills will help fund affordable housing and one will streamline local review of projects in cities and counties that haven’t met their regional housing goals, as set by the state and regional agencies.

While the affordable housing bills will help, even the billions they would set aside would be essentially a drop in the bucket compared to the need. The state is not in a position to subsidize its way out of a multi-decade long process of under-building homes.

That’s why the most effective solution is also the cheapest: take the shackles off homebuilders and let them build. That is the approach of the streamlining bill, Sen. Scott Weiner’s SB 35. Those shackles primarily involve local government policies that restrict development. They also involve myriad fees placed on developers to fund infrastructure improvements that used to be paid for by local governments, in the pre-Prop 13 days. And in other instances, they involve duplicitous, counter-productive “environmental review” mandated by a CEQA process that hasn’t caught up with current environmental needs.

But these shackles also involve high construction costs. Some of these costs are unavoidable impacts of the market and land scarcity. But many in the development community cite California wage standards as a major hurdle for building new units. And it’s greatly affected the debate around SB 35 to streamline project review, which includes a controversial prevailing wage provision (unions are still opposed to the bill though because without the local review, they lose a bargaining point to extract more worker benefits).

Liam Dillon in the Los Angeles Times has a helpful rundown of the impact of these “prevailing wage” standards that construction unions have helped put in place. Here’s a chart showing what this means in practice in a market like Los Angeles:

The article notes how challenging it is to estimate how much prevailing wage requirements add to construction costs, but it cites the following studies:

| Author | Percent Cost Increase |

|---|---|

| UC Berkeley | 9% to 37% |

| The California Institute for County Government | 11% |

| National Center for Sustainable Transportation | 15% |

| San Diego Housing Commission | 9% |

| Smart Cities Prevail | 0%* |

| Beacon Economics | 46% |

The bottom line is that prevailing wage adds costs, although we don’t know quite how much. But we do know it will slow housing production to some extent.

Of course, these requirements also bring significant benefits in paying good wages and helping to overcome the severe income inequality in the state. We want construction workers who are paid fairly for their work. But we also need more housing to lower costs for everyone else in the state. Hence the controversy.

More research on the impact of these wages would be helpful, as would discussions about alternative policies that could achieve the same ends without limiting housing production. For example, prevailing wage in hot markets like Los Angeles and the Bay Area probably won’t impact construction much. But in some of our more challenging markets that are most in need of infill development, like the Central Valley, and which are also most at-risk for sprawl, any additional requirements can sink a project before it starts.

In some ways, the prevailing wage debates fit into a larger discussion about how we ensure better living standards and wages for all in this country. Do we do it through mandates on the private sector? Or through taxes that we redistribute through social programs, to supplement private wages and benefits without directly burdening companies?

Ultimately, the state will need more creativity about how to address both challenges: wage growth and housing production, as well as more information about the scale of the impact and the potential alternative solutions available. But for now, the controversies are slowing the progress of major housing bills and potentially limiting their scope.

Joel Kotkin and Wendell Cox recently tried to explain falling transit ridership in the Orange County Register, offering an inaccurate diagnosis of the cause, along with counter-productive, infeasible solutions.

First, the problem of falling transit ridership they describe is definitely real and pressing:

[S]ince 1990, transit’s work trip market share has dropped from 5.6 percent to 5.1 percent. MTA system ridership stands at least 15 percent below 1985 levels, when there was only bus service, and the population of Los Angeles County was about 20 percent lower. In some places, like Orange County, the fall has been even more precipitous, down 30 percent since 2008.

Yet they attribute falling ridership solely to the sprawling “urban form” of Southern California, which they argue is too spread out to support much transit, particularly rail. But this factor doesn’t necessarily explain why transit ridership is down nationwide. While researchers are still examining it, it is likely due to a combination of larger trends such as low gas prices, more congestion from increasing vehicle miles traveled (which slows down buses), higher fares and decreasing service, and the rise of venture capital-subsidized Uber and Lyft.

Still, Cox and Kotkin are right that Los Angeles is generally a “spread out” city, with the downtown area employing just two percent of the region’s workers (although it has pockets of density to rival any eastern city, such as the Wilshire Corridor). As a result, transit — particularly rail — has a tougher time attracting sufficient riders in low-density areas. This decentralized pattern has also been the cause of the region’s severe traffic (and air quality) problems.

But then Kotkin and Cox — pardon the expression — go off the rails. In their view, Los Angeles’ sprawling urban form is the result of collective individual preferences, as expressed in a free market for housing — and not public policy interventions. They see the single-family home with a two-car garage and a driving commute as the dream that virtually every American wants to achieve.

According to this logic, any effort that makes it harder to live in suburban-type housing must be a form of social engineering by heavy-handed government officials or greedy developers, trampling the will of the home buyer. They use expressions to characterize this dynamic like “a growing fixation among planners and developers” and “the urbanist fantasies of planners, politicians and developers.”

And yet the evidence does not support their vision of the ideal housing situation. Land use is in fact one of the most regulated sectors of the economy, not the perfect expression of free market demand. The lack of density in economically thriving parts of Los Angeles has little to do with people’s aversion to “stack-and-pack” housing, as Kotkin and Cox term it. It is instead largely the result of highly restrictive zoning practices that prevent new multifamily housing near transit and jobs from getting built.

And yet the evidence does not support their vision of the ideal housing situation. Land use is in fact one of the most regulated sectors of the economy, not the perfect expression of free market demand. The lack of density in economically thriving parts of Los Angeles has little to do with people’s aversion to “stack-and-pack” housing, as Kotkin and Cox term it. It is instead largely the result of highly restrictive zoning practices that prevent new multifamily housing near transit and jobs from getting built.

Similarly, the suburban homes in communities far from job centers, like in the Inland Empire, are made feasible by public policies that subsidize the automobile and its related infrastructure. Basically, most home buyers have little choice: if you’re raising a young family, you’re likely priced out of expensive, job-rich neighborhoods due to the lack of new housing supply there. And you’re unlikely to want to live in high-crime urban areas with underperforming schools. As a result, your only option is cheap land in a far-flung suburban area.

Now to be sure, a sizeable percentage of home-buyers do want to live in suburban-style homes, but there are limits to that demand. In survey after survey, consumers report their strong preference for walkable neighborhoods and housing in proximity to jobs and schools. For example, a 2015 survey showed that 68% of Bay Area residents place a high or top priority on walkability for a home, while 50% want convenient access to transit from their home.

Furthermore, demographics run against the trend of suburbanization that Kotkin and Cox favor. Between 1970 and 2012, the share of households with married couples with children under 18 decreased by half, from 40 percent to 20 percent. Over that same period, the average number of people per household also declined from 3.1 to 2.6. To put it simply, these are not trends that argue for building more single-family, far-flung homes.

In short, Kotkin and Cox miss the policy support for decentralization and sprawl that contributes to the transit ridership problem. To reverse these negative ridership trends, policy makers should instead be lifting the barriers to new housing and commercial development near transit. They should also provide equitable funding for non-automobile infrastructure, such as bike lanes, pedestrian walkways, and transit. And they should price the externalities created by long-distance car commutes, such as through gas taxes that pay for the pollution and congestion pricing on crowded freeways and arterials.

But Kotkin and Cox instead advocate for unworkable solutions to address the ridership and mobility challenges. Specifically, they want more people to work from home, more Ubers and Lyfts, and a Hail Mary from autonomous vehicles to shuttle everyone around in robot cars.

First, working from home is not a viable long-term solution for many workers, given that only a certain percentage of jobs allow for this kind of arrangement, specifically office workers. Second, relying on Ubers and Lyfts, as well as autonomous vehicles, will only increase overall vehicle miles traveled in the region. This means more traffic overall, more lost open space, and more air pollution — all counter-productive results. And even if autonomous vehicles temporarily speed up freeway traffic, history has shown us time and again that increased road capacity only induces more car travel to fill it.

While Kotkin and Cox decry the worsening congestion from more “densification,” more compact neighborhoods actually decrease overall driving miles, even if congestion might worsen in the immediate areas. Along with sensible local parking policies, congestion pricing, and enhanced investments in transit, biking, and pedestrian infrastructure, the real solution is to create viable, compact neighborhoods close to jobs and transit, without forcing residents to be car dependent.

More of these transit-friendly communities would meet market demand and provide an alternatives for the growing demographic that is sick of business-as-usual housing options. It would also boost ridership on our buses and trains. But more of the status quo, as Kotkin and Cox propose, simply doubles down on failed policies that created the region’s mobility, economic, and quality-of-life problems in the first place.

California local governments have long been stymied in efforts to raise taxes for basic infrastructure and services by California’s constitution. Two voter-approved constitutional amendments, Propositions 13 and 218, require that any new local “special tax” (i.e. for a specific purpose and not for general revenue for the government) receive two-thirds voter approval.

California local governments have long been stymied in efforts to raise taxes for basic infrastructure and services by California’s constitution. Two voter-approved constitutional amendments, Propositions 13 and 218, require that any new local “special tax” (i.e. for a specific purpose and not for general revenue for the government) receive two-thirds voter approval.

It’s a high bar that has made it more difficult for locals to fund transit, parks, and other specific needs. And when local governments do secure two-thirds support, the initiatives are often the result of promises to spread the revenue around to make as many voters happy as possible, rather than prioritizing efforts to spend the money as cost-effectively as possible (the two are not always synonymous).

So it’s potentially a big deal that the California Supreme Court ruled today that any city or county “general tax” measure (i.e. not one for a specific purpose like transit or parks) that is placed on the ballot via the initiative process (a petition signed by 15 percent of the city’s voters) is not bound by Prop 218 requirements. Because the same logic could easily apply to “special taxes” that otherwise require a two-thirds supermajority, it potentially opens the door for much easier approval of any new tax measure placed by special interests.

The facts of California Cannabis Coalition vs. City of Upland involve a nonprofit that secured enough signatures to get a medical marijuana initiative on the ballot in the City of Upland. The initiative included proposed fees on new dispensaries, but the city council concluded the fees would constitute a general tax that needed to be placed on the ballot at the next general election.

The case ironically ended up being moot for these parties, as the Upland ballot measure was defeated handily by city voters. But the Supreme Court wanted to rule on the question as to whether or not Prop 13 and Prop 218 meant to restrict all local tax measures placed on the ballot, regardless of they got there — or just the ones placed on the ballot by “local governments” (i.e. the city, county or local agency).

Ultimately, the court concluded that the voter initiative power can only be limited when measures like Prop 13 or Prop 218 specifically state that they’re limiting these powers. Otherwise, they only apply to government entities like a city council or transportation agency.

The result may now be that any citizen, nonprofit or business group that wants to place a sales tax measure or fee on the ballot for something like a new school or transit line may only need a simple majority voter approval, provided they can get enough signatures for their measure. And unless barred by some other law, I gather there’s nothing stopping agency representatives or elected leaders in their individual capacities from sponsoring these campaigns in ways that essentially amount to the city, county, or agency sponsoring the measure themselves.

As an example, take a transit sales tax measure in a place like Los Angeles County. In the past, the county’s transportation agency, LA Metro, has sponsored these initiatives under their state law grant of authority, and the county supervisors have approved placing them on the ballot. Due to Prop 218, they’ve required two-thirds approval.

But now suppose an elected leader who serves on Metro, or a nonprofit or business group closely aligned with Metro, wants to place such a tax measure on the ballot. Provided they can fundraise for the signature gathering (which would be expensive in a county as large as Los Angeles), they would now only need a simple majority approval at the ballot box. In short, this decision could be transformational for local “self-help” efforts to fund badly needed infrastructure projects.

Or as Jon Coupal, head of the pro-Prop 13 Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association tweeted after the decision, described it:

CA Supreme Court rips huge whole in Prop 13 and Prop 218. Tax hikes by special interest groups may avoid 2/3 vote protection.

— Jon Coupal (@joncoupal) August 28, 2017

At a time when California is struggling to reduce emissions from the transportation sector due to growing commutes from the lack of housing and transit near jobs, this decision could be significant for finally allowing locals the flexibility they need to fund these investments. Under California Cannabis Coalition vs. City of Upland, local government finance for a host of environmentally significant projects, from parks to transit to infill housing infrastructure, may have just gotten easier to pass.

The unfolding tragedy in Houston from catastrophic rainfall and resulting flooding is probably worsened by two human-caused factors: climate change and bad land use planning. On the climate science, Michael Mann explains how warming waters in the Gulf of Mexico leads to greater rainfall:

The unfolding tragedy in Houston from catastrophic rainfall and resulting flooding is probably worsened by two human-caused factors: climate change and bad land use planning. On the climate science, Michael Mann explains how warming waters in the Gulf of Mexico leads to greater rainfall:

There is a simple thermodynamic relationship known as the Clausius-Clapeyron equation that tells us there is a roughly 3% increase in average atmospheric moisture content for each 0.5C of warming. Sea surface temperatures in the area where Harvey intensified were 0.5-1C warmer than current-day average temperatures, which translates to 1-1.5C warmer than “average” temperatures a few decades ago. That means 3-5% more moisture in the atmosphere.

That large amount of moisture creates the potential for much greater rainfalls and greater flooding. The combination of coastal flooding and heavy rainfall is responsible for the devastating flooding that Houston is experiencing.

But at the same time, the city is woefully unprepared for what appears to be a sadly predictable storm. Neena Satija previewed these events in a story last year in the Texas Tribune, in which she blamed poor local land use decisions for the city’s lack of resilience to this type of storm:

Scientists, other experts and federal officials say Houston’s explosive growth is largely to blame. As millions have flocked to the metropolitan area in recent decades, local officials have largely snubbed stricter building regulations, allowing developers to pave over crucial acres of prairie land that once absorbed huge amounts of rainwater. That has led to an excess of floodwater during storms that chokes the city’s vast bayou network, drainage systems and two huge federally owned reservoirs, endangering many nearby homes — including Virginia Hammond’s.

As my colleague Dan Farber notes on Legal Planet, this storm would have caused bad flooding no matter what. But locals throughout the country need to prepare for the “new normal” of climate change with storms and other events like these.

The resiliency planning will cost money and also mean other types of sacrifice. For example, in Houston’s case, large swaths of prairie should probably have been preserved rather than be developed. In other words, infill and smart growth development can be a crucial climate resiliency strategy. As a model here in California, I think of the Yolo Bypass by Sacramento and how that set aside of land for overflow from the Sacramento River saved the city from catastrophic flooding this year.

The events in Houston will hopefully be a wake-up call around the country that we need to preserve and bolster more natural systems to deal with the coming onslaught of extreme weather events, as well as build in smarter locations. And we’ll need forward-thinking people with the will to fund and implement these solutions.

Los Angeles County is a big place, with lots of urban centers to connect with rapid rail transit. Funding is limited for these expensive trains, despite the passage of two recent sales tax increases and two others passed in 1980 and 1990 respectively.

So why is the region spending these limited dollars on two rail lines in the mostly suburban, auto-oriented, low-density San Gabriel Valley? The issue is now front-and-center with the June approval of a $1.4 billion extension of the Foothill Gold Line light rail to Montclair.

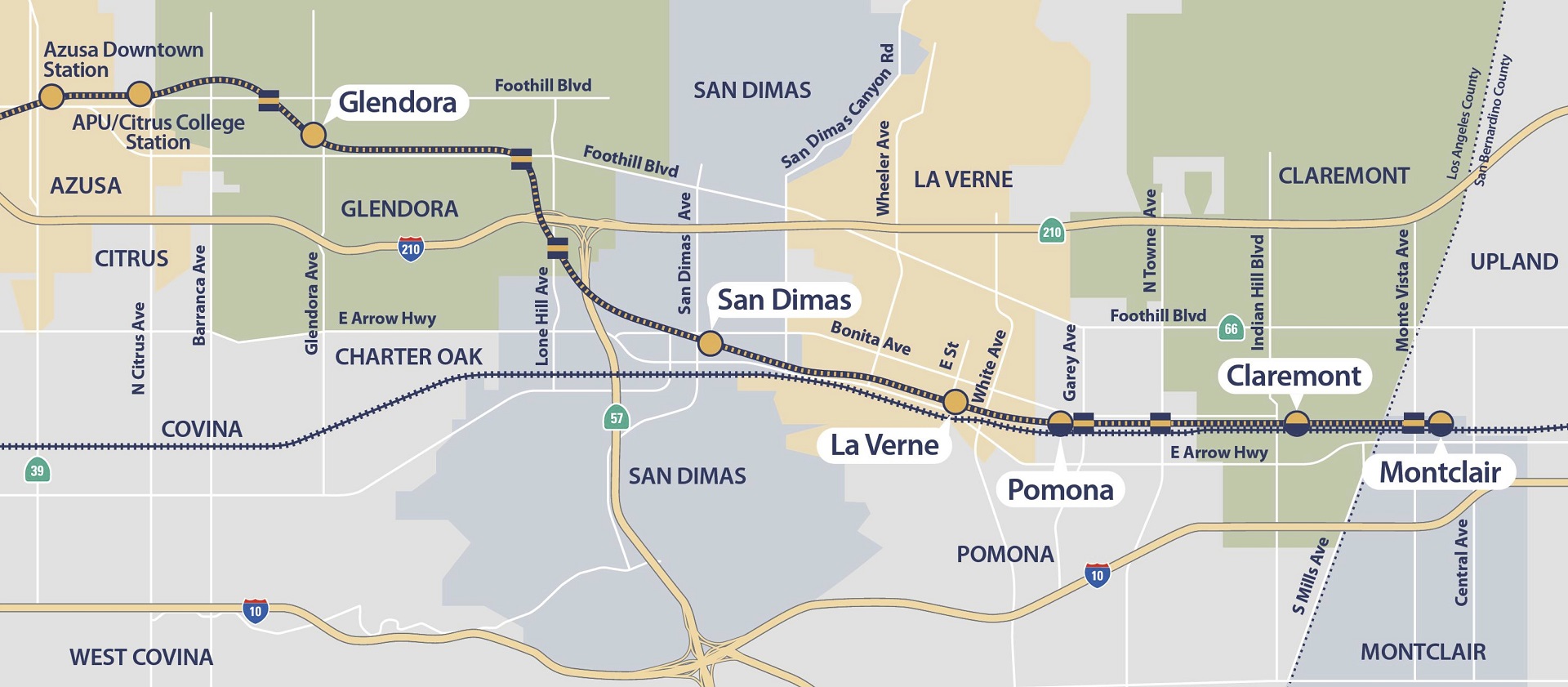

The problem is that the line dovetails with an existing Metrolink line, which is a diesel train for commuters into downtown Los Angeles. This map tells the story:

The existing Gold Line extension to Azusa already is cannibalizing nearby Metrolink service, as Urbanize LA reported:

In a report prepared for the Planning and Programming Committee, Metro staff notes that there has been a precipitous drop in ridership at a nearby station on the San Bernardino Metrolink line. In the year since the completion of the extension, which Metro calls the Gold Line Extension Phase 2A, boardings at Covina station have fallen 25 percent, despite being several miles from the Gold Line terminus at Azusa Pacific University.

Even more worrying for the future of Metrolink’s highest ridership line is the Gold Line Extension Phase 2B, which will extend the light rail line from Glendora to Claremont, and with a potential contribution from the County of San Bernardino, across the County line into Montclair. Three of the new stations, in the cities of Pomona, Claremont and Montclair, will be built in the Metrolink right-of-way and have stations directly adjacent to their commuter rail counterparts, offering perhaps an alluring alternative to the existing service. While Gold Line trains will take about 15 minutes longer to travel from Montclair to Union Station, they will be far cheaper and offer service every 7-12 minutes for most of the day.

I discussed this issue with KPCC radio recently, explaining that the reason for this extra rail service is simply politics. To secure two-thirds voter approval on the recent sales tax measures for transit, local leaders had to essentially buy off San Gabriel Valley leaders with a gold-plated rail line promise, even though the region doesn’t have the ridership to justify the expense.

That’s not to say that duplicative rail service is a bad thing by definition. If the population and job density is sufficient, two rail lines in proximity can make sense. But in this case, the density isn’t there. Metro leaders should have stood up to the San Gabriel Valley and funded a right-sized transit line. That would have most likely meant bus rapid transit and not light rail, which still would have been a big transit win for the region.

It may be too late to downsize the train route, but perhaps in the meantime Metro can develop adequate policies to ensure that San Gabriel Valley and Inland Empire leaders encourage maximum densities along the route. More dense development will not only give local residents more housing and commercial service options, it will provide more riders to minimize the losses on this unfortunate decision.

David Dayen in the American Prospect has a long piece describing the “revolt” in Los Angeles against the automobile and how the city is transforming before our eyes:

In January, the city received $1.6 billion in federal support for the Purple Line, and Mayor Garcetti has asked the Trump administration for more, to move up subway completion from 2035 to 2024, in time for that year’s Summer Olympics, for which L.A. is one of the two finalists. “We have become the infrastructure capital of the world,” says Phil Washington. “With two NFL teams, a rail spur to that stadium, the possibility of the Olympics, it creates this economic bonanza, what I call a modern-day WPA [Works Progress Administration].”

The risk, as Dayen points out, is that the Trump administration will withdraw federal funds, leaving Los Angeles to pay for much of this transformation on its own and essentially backfill the missing the federal dollars.

But cities have gone that way before. The Bay Area, for example, largely built BART on its own in the 1960s and 1970s, as the federal government didn’t provide funding for rail transit at the time.

The difference now is that costs have gone way up, making it harder for a region like Los Angeles to fund this transformation without getting its share of federal tax dollars back to reinvest locally.

The article also rightly points out (with some quotes from yours truly) that the great unanswered question is whether the region will allow growth to follow this new transportation infrastructure. Poor land use decision-making is what got the region into the mobility and air quality mess its in. Only smart growth near rail transit will provide residents the option of a way out.

But the necessary transit backbone, as Dayen describes, is finally coming into place, giving local leaders a viable foundation for rebirth.

Last night the California Legislature scored a super-majority victory to extend the state’s signature cap-and-trade program through 2030. It was a rare bipartisan vote, although it leaned mostly on Democrats. My UCLA Law colleague Cara Horowitz has a nice rundown of the vote and its implications, as does my Berkeley Law colleague Eric Biber on the bill.

Lost in the politics is what this means for high speed rail. The system has a fixed and dwindling amount of federal and state funds at this point, and it’s relying on continued funding from the auction of allowances under cap-and-trade to build the first segment from Fresno to San Jose and San Francisco.

Lost in the politics is what this means for high speed rail. The system has a fixed and dwindling amount of federal and state funds at this point, and it’s relying on continued funding from the auction of allowances under cap-and-trade to build the first segment from Fresno to San Jose and San Francisco.

If the auction was declared invalid or ended at 2020 with depressed sales, the system would be in major jeopardy of collapsing before construction even finished on the first viable segment. Now it has some assurance of access to funds.

But of course it’s not that simple. The bill that passed yesterday has diminished available funds set aside for the programs that have been funded to date with cap-and-trade dollars. As part of the political compromises, more auction money will now go to certain carve-outs, like to backfill a now-canceled program for wildfire fees on rural development.

And another compromise may put a ballot measure before the voters, passage of which would require a two-thirds vote for any legislative spending plan for these funds going forward. That means Republicans — who generally hate high speed rail — would be empowered to veto future spending proposals.

Still, high speed rail once again has a lifeline, as do the other programs funded by cap-and-trade, such as transit improvements, weatherization, and affordable housing near transit. It’s an additional victory beyond the emissions reductions that will take place under this extended program.

Joe Mathews usually writes insightful columns about California’s economic and environmental challenges. But he whiffed in yesterday’s piece in the San Francisco Chronicle extolling the virtues of the notorious “high desert corridor” freeway project in Southern California.

Joe Mathews usually writes insightful columns about California’s economic and environmental challenges. But he whiffed in yesterday’s piece in the San Francisco Chronicle extolling the virtues of the notorious “high desert corridor” freeway project in Southern California.

I’ve discussed the project briefly before, but it’s basically a gold-plated freeway. It’s hardly different than any other that Southern Californians have been building for over a half-century now, all of which have combined to create the region’s current sprawl, traffic, and air quality problems.

This particular freeway would connect Palmdale with Apple Valley in the ecologically sensitive high desert north of urban Los Angeles, just over the San Gabriel Mountains formed by the San Andreas Fault (see map above and below). It would run about 63 miles, in a three-to-six-lane configuration. That route is currently served by a slow-going, mostly two-lane highway through cities like Lancaster, Adelanto, Victorville, and Hesperia.

In terms of its environmental impacts, the freeway would allow those cities along the route and any new ones off the new freeway offramps to sprawl unobstructed over these desert sensitive lands. The end result will be a continued spread of the urban megalopolis over the desert.

So why is this freeway gold-plated? The project includes space for high-speed rail, an energy transmission line, and even a bicycle lanes in parts. Importantly, it would allow high speed rail (and many cars) to travel easily from Interstate 5 near the Grapevine to the San Joaquin Valley across the desert to Interstate 15 in Victorville and Apple Valley, en route to Las Vegas.

So why is this freeway gold-plated? The project includes space for high-speed rail, an energy transmission line, and even a bicycle lanes in parts. Importantly, it would allow high speed rail (and many cars) to travel easily from Interstate 5 near the Grapevine to the San Joaquin Valley across the desert to Interstate 15 in Victorville and Apple Valley, en route to Las Vegas.

Despite the sprawl risk, Joe Mathews seems to be enamored of the project in part because of this rail connection. But also because of the potential for easier goods movement:

Today, international trade is slowed in the L.A. Basin by the dense traffic in the seaports and on the streets. Advocates of the corridor say it could become a new “inland international port,” with logistics facilities, rail and local airports tied close together to move cargo. Such a port would allow the logistics industry to expand beyond the basin, bringing more jobs to the desert for local residents and shortening their commutes.

At the same time, the project could take traffic off of Los Angeles’ roads, while providing infrastructure to encourage more green technology and transportation. (On the less green side, supporters believe manufacturers will flock to the High Desert Corridor, because it is outside the basin and its air regulation.)

Mathews never once mentions the obvious concern with building yet another Southern California freeway: more inducement to build car-oriented sprawl, which leads directly to the exact challenges crippling Los Angeles: crushing traffic, poor air quality, and lack of open space. Not to mention a harsh quality of life spent car commuting all day. And any temporary alleviation of traffic in urban Los Angeles to the south will just induce more driving, as we’ve seen happen over and over again.

For this reason, environmental groups like Climate Resolve oppose the project. They note that the environmental review on the project failed to account for this sprawl inducement. Instead, the state’s transportation agency simply assumed in the environmental review documentation that this exurban growth will happen anyway. Conveniently, with that baseline in mind, this freeway (they argue) will in fact lessen traffic.

The story of Los Angeles should by now be obvious to everyone, especially Mathews: freeways don’t work at promoting smart land use, and they don’t alleviate traffic. They create more of it. And they crush a region’s environment, mobility, and quality of life in the meantime.

This project, with the exception of the needed high speed rail connection, should be stopped immediately, and Los Angeles leaders should ensure no more funding goes to support it.

Rather than reading Mathews’ column on it, we’d be better served reading Einstein: the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.