When SB 375 (Steinberg) passed in 2008, it got a lot of press as a fundamental change in transportation and land use in California. The law would now require regional transportation investments that promote smart growth, with the state setting a metric target for each region to reduce greenhouse gas emissions through less driving.

When SB 375 (Steinberg) passed in 2008, it got a lot of press as a fundamental change in transportation and land use in California. The law would now require regional transportation investments that promote smart growth, with the state setting a metric target for each region to reduce greenhouse gas emissions through less driving.

The law had some immediate problems though, which I outlined after the first regional transportation plan under the law was unveiled in San Diego in 2011. Namely, SB 375 failed to compel any changes in local land use policies, which is where the ultimate authority for permitting new housing lies (the state’s local government lobby added a provision to the original bill that the sustainable transportation plans would not affect local government land use plans).

Now a new National Center for Sustainable Transportation study [PDF] that surveys local land use responses to SB 375 confirms this weak impact on local decision-making. The authors surveyed planning departments in all cities and counties in California regions subject to SB 375 and received 180 responses out of 474 contacted. The found:

A majority of both county and city planning managers report that SB 375 had little to no impact on actions by their city to adopt or strengthen the eight smart growth strategies asked about in the survey. Responses to this effect were especially pronounced for the use of urban growth boundaries and of ag-land and open space preservation, suggesting that cities may have been motivated to support such strategies for other reasons, perhaps even before SB 375.

To be sure, the study highlighted some positives from SB 375 for local governments, primarily related to increased information sharing among them:

At the same time, a majority of cities and counties report that SB 375 has led to increased communication among local governments and other actors about land use issues and has led them to participate more in the regional planning process.

But ultimately the law fails fundamentally to change local government behavior:

When asked about the eight smart growth land use strategies, relatively few local governments anticipate that SB 375 will have a substantial impact on their cities in terms of specific costs or benefits.

In the end, SB 375 will not be a game-changer by itself but a policy foundation upon which more meaningful legislation can build. Examples of more impactful legislation include SB 743 (Steinberg, 2013) and this year’s SB 35 (Wiener, 2017). SB 375 provides some conceptual underpinnings and data to support these newer laws. But without any direct tie to local decision-making, SB 375 as it currently stands will not by itself solve California’s land use and transportation challenges.

Big industry loves to demagogue the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), which requires environmental review for major new projects. But a new survey from the State of California shows that the law barely affects most projects where the state is the lead agency.

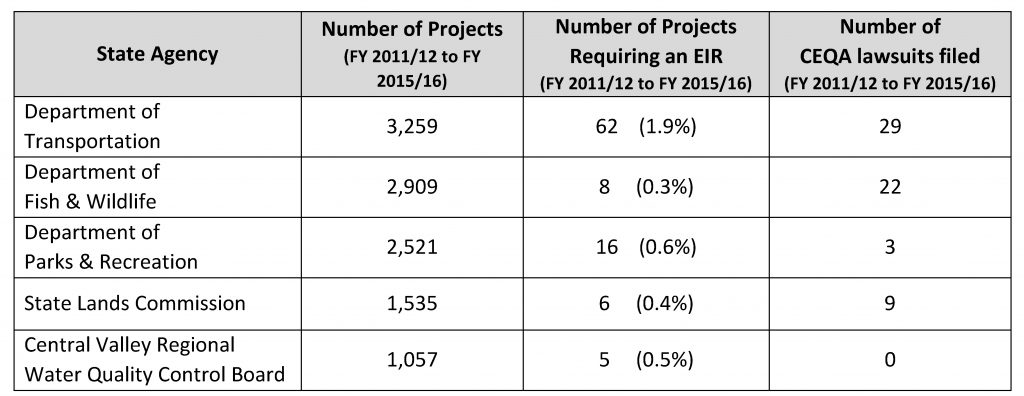

The study examined all state-led projects over a five-year period, from 2011 to 2016. First, 90% of the state’s projects were already exempt from the law, due to compliance with legislative or regulatory provisions that exempt certain types of projects. Second, a full-blown environmental impact report occurred less than one percent of the time, while litigation was virtually negligible. Here is the summary chart:

These findings are consistent with a 2016 study sponsored by the Rose Foundation, which found similarly low litigation rates (as I noted at the time):

These findings are consistent with a 2016 study sponsored by the Rose Foundation, which found similarly low litigation rates (as I noted at the time):

The number of lawsuits filed under CEQA has been surprisingly low, averaging 195 per year throughout California since 2002. Annual filings since 2002 indicate that while the number of petitions has slightly fluctuated from year to year, from 183 in 2002, to 206 in 2015, there is no pattern of overall increased litigation. In fact, litigation year to year does not trend with California’s population growth, at 12.5 percent overall during the same period.The rate of litigation compared to all projects receiving environmental review under CEQA is also very low, with lawsuits filed for fewer than 1 out of every 100 projects reviewed underCEQA that were not considered exempt. The estimated rate of litigation for all CEQA projects undergoing environmental review (excluding exemptions) was 0.7 percent for the past three years. This is consistent with earlier studies, and far lower than some press reports about individual projects may imply.

So while big polluters and sprawl developers and their law firm allies have gone to great lengths to demonize the law and the rare litigation that results, the facts just aren’t matching.

It’s still true that CEQA can be a barrier to new development. But based on the data so far, it’s just not a major one.

NIMBYs in Berkeley are getting some national attention. The New York Times covered a battle over a Berkeley home that a developer wanted to subdivide into three units. Despite compliance with the zoning code, neighborhood opponents convinced city leaders to reject the project. But a local YIMBY group sued and won to overturn the decision.

NIMBYs in Berkeley are getting some national attention. The New York Times covered a battle over a Berkeley home that a developer wanted to subdivide into three units. Despite compliance with the zoning code, neighborhood opponents convinced city leaders to reject the project. But a local YIMBY group sued and won to overturn the decision.

The article uses the story to describe the prevalence of single-family zoned neighborhoods around the state:

Neighborhoods in which single-family homes make up 90 percent of the housing stock account for a little over half the land mass in both the Bay Area and Los Angeles metropolitan areas, according to Issi Romem, BuildZoom’s chief economist. There are similar or higher percentages in virtually every American city, making these neighborhoods an obvious place to tackle the affordable-housing problem.

“Single-family neighborhoods are where the opportunity is, but building there is taboo,” Mr. Romem said. As long as single-family-homeowners are loath to add more housing on their blocks, he said, the economic logic will always be undone by local politics.

The article rightly points out the damage done by laws that enable this kind of exclusionary neighborhood, particularly to housing affordability and the environment.

Adding fuel to the fire, former Berkeley planning commissioner Zelda Brownstein published a controversial piece in Dissent Magazine arguing that there is no credible evidence to support the claim that local opposition prevents housing from getting built, despite numerous studies, surveys and observable evidence around California to the contrary. She writes:

Developers build housing, and what they decide to build—and when and whether they decide to build it at all—depend on factors that over which local governments have no control: the availability of credit, the cost of labor and materials, the cost of land, the current stage of the building cycle, perceived demand, and above all, the anticipated return on investment.

Some of the same YIMBYs that fought the Berkeley housing decision quickly returned fire, noting Ms. Brownstein’s conflict of interest as a landlord who benefits financially from the lack of new housing:

You guessed it correctly: what these 9 rental properties (valued $32M altogether) have in common is their ownership! They all belong to: BRONSTEIN ASSOCIATES LLC C/O ZELDA BRONSTEIN. Yes, as in the Berkeley NIMBY and now infamous author of https://t.co/qQCrlA3jhS https://t.co/XMXZvpUho6

— SF NIMBY Watch (@sfnimbywatch) December 5, 2017

Personally, I’m not a fan of these kind of personal attacks, as Brownstein’s arguments should be evaluated on their own merits, not based on who is making them.

But as California residents grow increasingly frustrated with NIMBY activity stifling new homes, these kinds of debates and news coverage will only increase.

Some longtime rail opponents made an appearance in the Los Angeles Times op-ed pages last month, with a bus-only solution to recent transit ridership woes. James Moore from USC teamed up with former Southern California Rapid Transit District chief financial officer Tom Rubin to blame falling transit ridership on L.A. Metro’s lack of investment in buses compared to rail.

Moore and Rubin went to lengths to extol the benefits of the now-expired 1990s consent decree to settle a lawsuit against L.A. Metro by the Bus Riders Union. The settlement decree forced L.A. Metro to privilege spending on buses over rail:

The settlement allowed Metro to build all the rail it could afford, so long as specific bus service improvements were made too. Those improvements included reducing fares, increasing service on existing lines, establishing new lines, replacing old buses and keeping the fleet clean. Lo and behold, while the decree was in force L.A.’s transit ridership rose by 36%. When Metro was no longer bound by the settlement, it refocused its efforts almost exclusively on new rail projects. The quality of bus service began declining in almost every way measurable, and overall ridership again fell.

Moore and Rubin’s 2017 op-ed hasn’t actually changed much since their 2008 version in the same paper. But their claim that the consent decree boosted L.A.’s transit ridership by 36% sounds different from the 2008 op-ed. In that original piece, they acknowledged that the ridership boost during the consent decree also included rail riders, given the new lines being unveiled at the same time:

Over the next 11 years, [L.A. Metro] added buses, started new lines and held fares in check to improve the country’s most overcrowded bus system. As a result, users of public transit gradually started to increase again. Yes, some chose the Blue, Red, Green and new Gold rail lines, but the majority of riders returned to buses.

“Gradually started to increase” in 2008 doesn’t seem to match their 20017 claim of a 36% boost. Meanwhile, Bus Riders Union estimates of ridership during the consent decree years was evidently 1% per year increase, per the LA Weekly in a 2005 article. That’s not much to get excited about, given the scale of the ridership problem and the amount of money L.A. Metro spent on consent decree compliance.

I certainly agree that lower bus fares can mean more ridership, and I support improved bus service. But the idea that the consent decree was a big ridership win seems like revisionist history. More importantly, Moore and Rubin’s arguments fail to put the L.A. transit ridership problem into the national context it deserves. With low gas prices and a booming economy, plus the impact of Uber and Lyft, transit ridership decreases are happening everywhere. This isn’t just about L.A. Metro’s decision to build a lot of rail.

A true response to the challenge involves multiple solutions, of which better bus service and lower fares are just one arrow in the quiver. More dense development around transit and congestion pricing also need to be in the mix, for example. Focusing only on ideologically motivated solutions, introduced regardless of context, is less likely to be an effective approach to tackling the problem.

It’s taken a long time, but California finally is ready to make a significant change to speed environmental review for new transit and infill projects. The Governor’s Office of Planning & Research (OPR) announced on Monday that a compromise has been reached to implement SB 743 (Steinberg, 2013), a law that made major amendments to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), the state’s law governing environmental review of new projects.

Back in 2013, the legislature passed SB 743 to change how infill projects undergo environmental review. Under the traditional regime, project proponents had to measure transportation impacts by how much the project slowed car traffic in the immediate area. The perverse result was mitigation measures to privilege automobile traffic, like street widening or stoplights for rail transit in urban environments or new roadways over bike lanes in sprawl areas.

But the true transportation impacts are on overall regional driving miles. An urban infill project may create more traffic locally but can greatly reduce regional traffic overall by locating people within walking or biking distance of jobs and services. Meanwhile, a sprawl project may have no immediate traffic impacts, but it typically dumps a huge amount of cars on regional highways, leading to more traffic and air pollution. As a result, the switch from the “level of service” (auto delay) metric to “vehicle miles traveled (VMT)” made the most sense. Most infill projects are exempted entirely under this metric, while sprawl projects would have to mitigate their impacts on regional traffic.

But OPR’s implementing guidelines with this change were held up by highway interests and their government allies, who don’t want the law to apply to highways. You can probably see why: highways are designed to do one thing only — induce more driving. And that would score poorly under this change to CEQA.

State leaders finally reached a compromise this month: the new guidelines could apply statewide to all projects (something only suggested by the statute), but new highway projects can still use the old “level of service” metric, at the discretion of the lead agency (see the PDF of the guidelines for more details at p. 77).

It’s an unfortunate but probably necessary concession to powerful highway interests. Even though freeways have consistently failed to live up to their promise of fast travel at all times, and instead brought more traffic, sprawl and air pollution to the state, many California leaders are still wedded to this infrastructure investment.

My hope is that the compromise won’t actually mean that much new highway expansion in the state. First, California isn’t planning to build a lot of new highways, outside of the ill-advised “high desert corridor” project in northern Los Angeles County. Second, even for new highway projects, CEQA’s required air quality review may necessitate an analysis of (and mitigation for) increased driving miles.

Either way, smart growth advocates can at least celebrate the good news that CEQA will finally be in harmony with the state’s other climate goals on infill development, transit, and other active transportation modes.

The guidelines though still need to be finalized by the state’s Natural Resources Agency, which will take additional months. I’ll stay tuned in case anything changes with the proposal during this time.

California is on track to meet its 2020 climate change goals, to reduce emissions by that year back to 1990 levels. Much of that success is due to the economic recession back in 2008 and significant progress reducing emissions from the electricity sector, due to the growth in renewables.

But the state is lagging in one key respect: transportation emissions. Bloomberg reported on the emissions data compiled by the nonpartisan research institute Next 10:

But the state is lagging in one key respect: transportation emissions. Bloomberg reported on the emissions data compiled by the nonpartisan research institute Next 10:

In 2015, the most recent year for which data are available, the state’s greenhouse gas emissions dropped at less than half the rate of the previous year, according to an August report from the San Francisco-based nonprofit Next 10. Low gas prices and a lack of affordable housing prompted more driving and contributed to a 3.1 percent increase in exhaust from cars, buses, and trucks, the report says. Census data show that more than 635,000 California workers had commutes of 90 minutes or more in 2015, a 40 percent jump from 2010.

The solutions are urgent: we need to reduce driving miles by building all of our new housing (an estimated 180,000 units needed per year) near transit, and we need to electrify our existing vehicle fleet and add in biofuels and hydrogen where appropriate. Otherwise, the state will not be as successful in meeting its much more aggressive climate goals for 2030, with a 40% reduction below 1990 levels called for that year.

First, advocate for a multi-billion transit line that will serve your home neighborhood. Then once it’s built, make sure nobody else can move to your neighborhood to take advantage of the taxpayer-funded transit line. It’s a classic bait-and-switch, and it’s happening now along the Expo Line in West L.A.

What’s at stake is an already-watered down city plan for rezoning Expo Line stations areas. The city’s “Exposition Corridor Transit Neighborhood Plan,” while rezoning some station-adjacent areas for higher density, still leaves a whopping 87% of the area, including most single-family neighborhoods, unchanged, and with too-high parking requirements to boot.

But this weak plan is still too much for Los Angeles City Councilmember Paul Koretz and his homeowner allies, including an exclusionary group of wealthy homeowners assembled under the name “Fix The City.” They oppose even these modest changes to land use in the transit-rich area. Essentially, they’ll get the financial and quality-of-life benefit of the Expo Line, while working to ensure no one else does.

As Laura Nelson details in the Los Angeles Times:

Koretz told the Planning Commission this month that the areas surrounding three Expo Line stations in his district “simply cannot support” more density without improvements to streets and other public infrastructure.

It’s a view shared by advocates from Fix the City, a group that has previously sued Los Angeles over development in Hollywood and has challenged the city’s sweeping transportation plan that calls for hundreds of bicycle- and bus-only lanes by 2035.

“It’s like when you buy a new appliance, you’d better read the fine print,” said Laura Lake, a Westwood resident and Fix the City board member. “This is not addressing the problems that it claims to be addressing.”

If Koretz and his allies have their way, their homeowner property values will go up with the transit access, but taxpayers around the region have to continue subsidizing the line even more because neighbors are not allowing more people to ride it. And to boot, they will keep regional traffic a mess by not allowing more people to live within an easy walk or bike ride of all the jobs near their neighborhood. Essentially, they force everyone else into long commutes while keeping housing prices high — an ongoing environmental and economic nightmare.

Thankfully there are others mobilizing against these homeowner interest groups, such as Abundant Housing L.A. But two things need to happen now: first, the Expo neighborhood plan needs serious strengthening, including elimination of parking requirements and an end to single-family home zoning near transit stops. Second, L.A. Metro needs to hold the hammer over these homeowners by threatening to curtail transit service to the area. I see no reason why taxpayers should continue to support service to an area that won’t do its part to boost ridership on the line.

Single-family zoning near transit is an idea that should have died long ago. It has no place in a bustling, modern, transit-rich environment like West L.A. The Expo Line bait-and-switch must end.

Scott Wiener, San Francisco’s state senator elected in 2016, has already authored some landmark legislation on housing (SB 35), and he’s co-authored other measures related to transportation and leading the state resistance to the Trump administration.

Scott Wiener, San Francisco’s state senator elected in 2016, has already authored some landmark legislation on housing (SB 35), and he’s co-authored other measures related to transportation and leading the state resistance to the Trump administration.

I’ll be interviewing him tonight on City Visions at 7pm to discuss these issues and what Sen. Wiener sees on tap legislatively and politically for the state in 2018. Tune in on KALW 91.7 FM in the San Francisco Bay Area or stream it live. We welcome your questions and comments!

California’s Central Valley is the state’s defining geographical feature. It’s the country’s breadbasket, with over 400 commodity crops, including all the almonds grown in the country. At the same time, it’s poverty-stricken, with Fresno the second poorest city in the U.S., and yet oil rich down by the deeply Republican Bakersfield.

California’s Central Valley is the state’s defining geographical feature. It’s the country’s breadbasket, with over 400 commodity crops, including all the almonds grown in the country. At the same time, it’s poverty-stricken, with Fresno the second poorest city in the U.S., and yet oil rich down by the deeply Republican Bakersfield.

It’s also one of the most environmentally vulnerable region in the state, with one of the most polluted air basins in the country. And as the Los Angeles and San Francisco Bay Area regions say no to new housing, sprawl is spreading into the Valley from these areas, as workers choose cheap housing and super commutes. Sprawl is also the norm around the Valley’s large cities along Route 99 on the eastern side. Like Los Angeles before it, the flat terrain means the region has no real geographical impediments to sprawl.

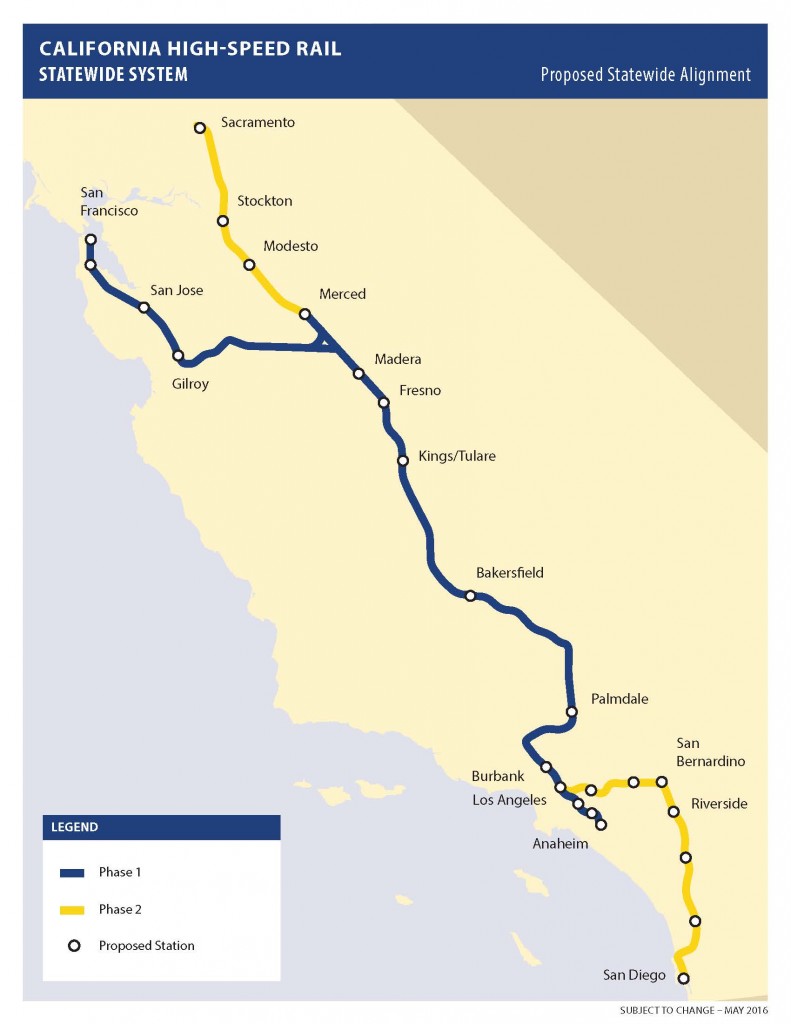

High speed rail could make the sprawl even worse, as the train will spur growth in places like Fresno, which will be just an hour or so from the booming coastal job centers (Berkeley and UCLA Law released a report on the subject in 2013, along with recommendations to combat the problem).

High speed rail could make the sprawl even worse, as the train will spur growth in places like Fresno, which will be just an hour or so from the booming coastal job centers (Berkeley and UCLA Law released a report on the subject in 2013, along with recommendations to combat the problem).

People in the Valley are well aware of the risk. Former Fresno mayor Ashley Swearengin, a rare Republican high speed rail supporter, tried to do the right thing to encourage more downtown-focused growth in Fresno and not allow the urban core to get hollowed out by competition from nearby cheap sprawl.

But Mayor Swearengin and other downtown booster’s efforts are threatened by Fresno’s neighbor Madera County next door, whose leaders prefer the model of continued sprawl over productive farmland and open space. The result will be the usual negatives we see elsewhere in the state: more traffic, worse air quality, and lost natural resources.

Marc Benjamin and BoNhia Lee detailed the new sprawl projects in the Fresno Bee last year:

Madera County is on the verge of a building boom that creates the potential for a Clovis-sized city north and west of the San Joaquin River, with construction starting this spring.

Riverstone is the largest of the approved subdivisions in the Rio Mesa Area Plan. It’s underway on 2,100 acres previously owned by Castle & Cooke on the west side of Highway 41 and north and south of Avenue 12. Castle & Cooke had plans to build there for about 25 years.

It’s the first of several subdivisions in the county’s area plan to be built. Over the past 20 years, Riverstone and other projects were targeted in lawsuits, many of which have been settled, but some still linger. But some critics contend that the new developments will worsen the region’s urban sprawl.

Principal owner Tim Jones’ vision for his nearly 6,600-home development a few miles north of Woodward Park is a subdivision with six separate themed districts. Riverstone will compete for home buyers with southeast Fresno, northwest Fresno, southeast Clovis and a new community planned south and east of Clovis North High School.

The Rio Mesa Area Plan will result in more than 30,000 homes when built out over 30 years. About 18,000 homes have county approval. The contiguous communities could incorporate to create a new Madera County city that could dwarf the city of Madera and have a population greater than Madera County’s current population of 150,000.

In the coming years, an additional 16,000 homes are proposed in Madera County. On the east side of the San Joaquin River, in Fresno County, about 6,800 homes are approved in the area around Friant and Millerton Lake.

Defenders of these sprawl projects claim that some are mixed-use developments located close to distributed job centers, minimizing the chances that they will become merely bedroom communities of Fresno. But as the development continues outward, it undercuts the market for infill housing, leading to a vicious downward spiral that we saw hit downtowns throughout the country in the middle of last century.

The best way to solve these growth issues is better regional cooperation, particularly around some type of urban growth boundaries. The growth boundaries can be de facto through mandatory farmbelts, rings of solar facilities, and possibly better pricing on sprawl projects to account for their externalities. Or they can be actual limits on growth and urban expansion outside of already-built areas.

Without concerted action, and with the high speed rail coming from Fresno to San Francisco soon, we may soon find that it’s too late to undo the damage in the Central Valley.

A double shot of autonomous vehicle news this morning should be a wake-up call for those who don’t think fully self-driving vehicles will get here anytime soon:

- Waymo announced that it is ditching the backup drivers for its “robot cars” in Chandler, Arizona, and will offer them to the public as an autonomous taxi fleet, per the San Francisco Chronicle.

- Also in the Chronicle, Las Vegas is hosting a driverless shuttle for a half-mile, all-day loop in the downtown Fremont East district. AAA of Northern California, Nevada, and Utah is sponsoring the yearlong pilot program, along with French companies Keolis (a global transportation company that already runs Las Vegas’ public bus system) and Navya, which manufactures the driverless shuttle.

With this news, the urgency of the situation should be clear to policy makers concerned about runaway sprawl and traffic. Having a robot chauffeur will encourage significantly more driving, if we don’t take policy steps to curb usage. I outline some of the options here, such as pricing driving miles as opposed to fuel.

The future is upon us with autonomous vehicles, and this single technology (which otherwise promises tremendous benefits for the public) could end up being an environmental and quality-of-life disaster if we don’t get ahead of it.