The “Gimme Shelter” podcast, a regular show dedicated to all things housing in California, interviewed me for a new episode releasing today on the tension between infill housing advocates and some environmental groups.

Specifically, the hosts, Los Angeles Times state policy report Liam Dillon and CalMatters Matt Levin, asked me about the 2017 UC Berkeley/Next 10 report Right Type, Right Place on infill housing, SB 827 (Wiener), CEQA, and other climate & housing topics. They cover other housing issues in the first half of the podcast (my interview starts about 29 minutes in).

Tune in here (and don’t forget to subscribe to their podcast if you haven’t already):

One of the common knocks on allowing new home-building near transit (as SB 827 would allow) is that it will displace low-income renters and gentrify low-income neighborhoods. The nightmare scenario for these tenants is that a developer buys and demolishes their low-income, single-family or small multi-unit building and then builds a luxury mid-rise in a fast-gentrifying neighborhood. The tenants are kicked out and can’t find comparably priced housing in their neighborhood.

One of the common knocks on allowing new home-building near transit (as SB 827 would allow) is that it will displace low-income renters and gentrify low-income neighborhoods. The nightmare scenario for these tenants is that a developer buys and demolishes their low-income, single-family or small multi-unit building and then builds a luxury mid-rise in a fast-gentrifying neighborhood. The tenants are kicked out and can’t find comparably priced housing in their neighborhood.

But let’s explore why this dynamic might happen. A neighborhood is more likely to “gentrify” if higher-income people can’t find new housing elsewhere. They’ll buy up existing buildings in places like San Francisco’s Mission or Venice in Los Angeles, which otherwise house predominantly low-income residents.

And why can’t any of these tenants who are kicked out find comparably priced housing nearby? Primarily because local governments haven’t allowed enough new home-building, particularly subsidized affordable units, to stabilize prices and give low-income residents a chance to stay in their communities. So the current housing shortage puts displacement and gentrification on steroids.

Yet many advocates for low-income renters continually shoot down options to build new market-rate housing, even if that market-rate housing would include fees and requirements to build a certain amount of affordable units. Their argument is that the “luxury housing” that would result will only contribute to gentrification and displacement.

So what does the academic literature have to say on this subject? The Urban Displacement Project at UC Berkeley (in collaboration with researchers at UCLA and Portland State) tackled this question in a research brief last year. Here are their key findings, based on a study of the relationship among housing production, affordability and displacement in the San Francisco Bay Area:

- At the regional level, both market-rate and subsidized housing reduce displacement pressures, but subsidized housing has over double the impact of market-rate units.

- Market-rate production is associated with higher housing cost burden for low-income households, but lower median rents in subsequent decades.

- At the local, block group level in San Francisco, neither market-rate nor subsidized housing production has the protective power they do at the regional scale, likely due to the extreme mismatch between demand and supply.

The key takeaway here is that new affordable housing provides the most “bang for the buck” in terms of reducing displacement and gentrification pressure.

But the study also indicates that new market-rate housing may have three primary benefits for low-income tenants:

- It can reduce displacement pressure overall (although less so than new affordable units).

- This housing stock eventually “filters” over the coming decades into low-income housing, as it gets older and therefore less desirable to higher-income earners. As a result, it provides an investment in the unsubsidized housing of the future (most low-income residents live in market-rate housing, not subsidized units).

- New market-rate development can provide local governments with the revenue they need to fund new subsidized units, via impacts fees, inclusionary zoning, or higher tax revenue.

There’s no denying that displacement is a genuine concern, and policies to promote new housing need to take that concern into account. But opposing new market-rate housing, particularly near transit, is not a solution. In fact, it’s part of the problem.

Housing more Californians near transit and not in sprawl areas represents one of the most crucial ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Senate Bill 827 (Wiener) would help do just that, by preventing local governments from zoning people (and homes) out of these prime transit areas. So it was surprising to see an environmental organization like Sierra Club California come out against the bill (here is a PDF of their letter).

Just how high are the environmental stakes of SB 827? Berkeley Law, together with the Terner Center and Next 10, recently analyzed the impact of putting all new residential development in California through 2030 within three miles of transit or in low-vehicle miles traveled neighborhoods (areas without rail but where residents drive at low rates) and found the following impacts:

Annual reductions of 1.79 million metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions compared to the business-as-usual scenario, which is the equivalent of taking 378,000 cars off the road and almost 15 percent of the emissions reductions needed to reach the state’s Senate Bill 375 (Steinberg, 2008) targets from statewide land use changes.

Significantly, the geography we examined was farther from transit than what SB 827 encompasses, which only covers up to one-half mile near major transit. So the greenhouse gas savings and air quality improvements from building new homes near transit will be significantly greater under SB 827.

So why would Sierra Club oppose what is arguably the state’s most important climate bill this term (as the New York Times couches it)? Let’s go through their arguments:

First, they argue the SB 827 will fuel neighborhood opposition to new transit. Why would neighbors want to support a new rail line, Sierra Club argues, if it will force them to allow new people in their community who will want to live near it? Perhaps the Sierra Club doesn’t realize it, but they just made an important point in favor of SB 827. The better question is: why should we build expensive new rail lines through low-density communities, when they refuse to provide the ridership necessary to support these taxpayer investments? SB 827 is actually a great way to weed out bad rail projects with weak ridership in favor of more sensible transit investments, like bus-only lanes or rail in areas that can actually support it.

Second, they argue that bus routes and service changes all the time, so frequent transit service now might be reduced, leaving SB 827-style dense development underserved by buses. But if you look at the maps of bus routes served with 15 minute peak headways, they cover major arterials that would be among the last places a transit agency would peg for service reduction, like Van Ness Avenue in San Francisco and Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles. And if Sierra Club is really concerned about service reductions, why not recommend an amendment that the bus routes must have been in service at 15 minute commute headways for a minimum period of time for SB 827 to qualify? Otherwise, this seems like a weak reason to oppose the bill outright.

Third, they are worried about displacement of low-income renters near transit. As I’ve blogged before, this is a legitimate yet overblown concern. Gentrification and displacement is happening now like crazy, precisely because we’re not building enough housing overall. Furthermore, developers will build in upscale transit areas where they can get higher returns, not in low-income neighborhoods. For example, a UCLA study examining low-income neighborhoods around the Blue Line light rail from Downtown Los Angeles to Long Beach showed virtually no investment in these areas, despite some very relaxed local zoning.

But if Sierra Club is truly concerned about displacement, why not recommend policies to address it in the bill, such as requirements for inclusionary zoning or density bonuses? Instead, they offer no solutions, while failing to recognize the massive displacement already occurring due to the existing housing shortage. My question for Sierra Club: what do they propose to combat the gentrification and displacement currently happening now? And where do they want new homes to be built, if not in these prime transit areas?

Fourth, they argue for more incentives on growth instead of a state-based approach like SB 827. But incentives only go so far when you’re up against well-heeled homeowner groups who will vote out elected officials who don’t toe the exclusionary line. What incentives does Sierra Club believe might entice Westwood to upzone their single-family zoning around the Expo Line? Or Rockridge around its BART station? Let’s face it — local control in transit-rich, upscale areas mean the forces of exclusion win. Hence the critical need for approaches like SB 827.

Finally, Sierra Club complains that some of these new buildings near transit won’t need to undertake environmental review under the California Environmental Quality Act, based on last year’s SB 35. This is a bit of a convoluted argument. SB 35 only applies to jurisdictions behind on affordable housing production. The projects that are then eligible for SB 35 CEQA streamlining must otherwise meet strict requirements and be compliant with local zoning, including providing a significant amount of affordable housing on-site (addressing the displacement concerns Sierra Club raised earlier). So the universe of projects that escapes CEQA review under SB 35 is already pretty minimal.

But more importantly, if you follow this line of argument, now that SB 35 is in effect, Sierra Club is basically saying they won’t favor any zoning changes to allow new housing in communities that are behind on producing affordable units because it might mean CEQA doesn’t apply to projects consistent with that zoning. I don’t think that’s a position Sierra Club really wants to take.

Overall, Sierra Club California appears to be at a reputational crossroads here on smart growth. Their image on this issue took a big hit when wealthy property owners used the San Francisco chapter to oppose new housing in the city, precisely the low-carbon area where new housing should go. So is Sierra Club an organization of wealthy homeowners who want to keep newcomers out of their upscale, transit-rich areas? Or are they actually committed to fighting climate change by providing enough housing for Californians in low-carbon, infill areas? Because their opposition to SB 827 unfortunately indicates more of the former than the latter.

If passed as is, SB 827 (Wiener) could have a big impact on neighborhoods adjacent to rail and major bus transit in California by requiring local governments to relax development restrictions there. But simply stating “one-quarter mile” or “one-fourth mile” radius from these stops is not that helpful for most people to visualize where the affected neighborhoods are located, particularly when the bill currently includes some areas with “transit corridors” — and not just transit stops.

Fortunately, a tech-savvy (former Redfin CTO) SB 827 fan with time on his hands developed a very useful interactive map. If you live in California (or interested in what happens here), you can now click on Sasha Aickin‘s map and see how any particular city or county might be affected by the bill.

But perhaps more importantly, regardless of what happens with SB 827 during this legislative process, the map shows the battleground in California where we desperately need more housing to be built. All of the highlighted areas are prime transit-oriented spots, where residents can easily bike or walk to access transit. Study after study shows that development in these areas is what makes or breaks transit ridership.

And for a place like California, with its longstanding housing shortage, it also shows where badly needed new residential development would be most appropriate from an environmental perspective.

Happy viewing!

Scott Wiener’s revolutionary SB 827 proposal to ease local restrictions on transit-oriented development is part of a growing legislative trend to tie development incentives to proximity to major transit stops. These stops are defined to include those with frequent bus service. As a result, some pro-growth advocates worry that NIMBYs will respond by lobbying their transit agencies to decrease bus service in their neighborhoods so developers can’t access these benefits and build more in their area.

But what about the opposite problem, where developers lobby transit agencies to increase bus service, merely to get some of the permit streamlining and density boosts that would follow? The danger is that transit agencies would comply, perhaps as a favor to a politically connected developer, but the project at issue wouldn’t actually be transit-oriented or otherwise justify the increased transit service.

And a worse situation might involve the transit agency increasing bus service only temporarily to qualify the project for the land use and permitting benefits, and then later reduce the service. The consequence could be a type of “density sprawl” with projects that wouldn’t serve transit (or have transit serve them) and instead increase overall driving miles and pollution.

And a worse situation might involve the transit agency increasing bus service only temporarily to qualify the project for the land use and permitting benefits, and then later reduce the service. The consequence could be a type of “density sprawl” with projects that wouldn’t serve transit (or have transit serve them) and instead increase overall driving miles and pollution.

To be clear, we want to encourage development near major bus stops. And this policy trend of tying incentives to transit proximity started before SB 827. For example, SB 375 (Steinberg, 2008) provides permitting relief through streamlining provisions under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) for projects within 1/2 mile of a major transit stop, including frequent bus stops. Similarly, SB 743 (Steinberg, 2013), also relaxes CEQA’s transportation impact analysis for projects in these areas.

But both possibilities of manipulating bus service either to 1) avoid new development in the right transit-oriented areas or 2) facilitate car-oriented projects in less transit-friendly areas would be bad.

What’s the solution? Transit agencies will need to develop strong and transparent standards governing their decisions about when to expand or retract major bus service (defined as 15 minute peak headways during commute times). Follow-up state legislation could potentially accomplish this outcome by mandating such standards on local transit agencies (something these transit agencies would probably hate). Or transit agencies that don’t already have such policies on the books could adopt such standards on their own, perhaps using some best practice examples from around the state and country.

Right now, I don’t think this kind of transit service manipulation is a serious problem, although I’ve started to hear some anecdotes from local transit agencies. But if SB 827 passes in anything like its current form, it may become an issue that policy makers at either the local or state levels will need to address.

In my excitement over SB 827, the new bill that would dramatically boost badly-needed new housing in job- and transit-rich areas in California, I overlooked one potentially important source of opposition: low-income renters near transit. As I described, the bill would limit local restrictions on height, density and parking near transit. I assumed that these changes would mostly affect relatively affluent single-family home neighborhoods near transit, whose residents and allied elected officials often prevent new housing for reasons ranging from the deplorable (racism) to the understandable (fear of more traffic and related hassles).

But for renters and their advocates in existing low-income neighborhoods near major transit stops, the SB 827 approach raises different fears: eviction through displacement and gentrification. They fear the relaxed local government rules under SB 827 will prompt developers to gobble up their existing low-income buildings, evict the tenants, tear down the structures, and then build market-rate housing for people with much higher-income levels. In short, they see SB 827 putting displacement and gentrification in these transit-rich, low-income communities on steroids.

The fear is legitimate, though I believe potentially overstated, depending on the neighborhood. And it’s also something that can be mitigated, with the right policy approach. First, it’s probably overstated because development in low-income communities is not necessarily held back only by strict local zoning. For example, as UCLA scholars Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris and Tridib Banerjee described in a report examining neighborhoods around the Blue Line light rail from Downtown Los Angeles to Long Beach, low-income areas near the station stops have received virtually no investment in real estate despite sometimes very relaxed local zoning.

The problem in many of these neighborhoods is that demand is not sufficient to attract developers and capital needed to build multistory buildings. These relatively expensive structures must net high rents to justify the higher construction costs. Compounding matters, many low-income neighborhoods often require significant infrastructure upgrades to accompany any new buildings. All of these factors deter developers from investing — not the local zoning codes. Ultimately, capital will flow to the areas that promise the highest return: which means relatively affluent neighborhoods near transit will see the most construction under the SB 827 approach.

Still, those economic dynamics probably won’t by themselves allay the fears of low-income renters and their advocates. Many of the neighborhoods they care about are at risk of gentrification, which means rents could increase, higher-income residents would move in with new construction, and low-income renters forced out.

So what can be done in these situations? There’s a rich literature on the subject, but one of the best ways to mitigate these impacts is to ensure a percentage of the new homes built are available exclusively to people with low incomes. Furthermore, local residents who have been displaced or are at risk of displacement should have priority access to these new homes.

The state already has policies on the books to encourage this type of affordable housing construction, from a now-stricter regional housing needs process (which requires locals to plan and zone for affordable housing in their jurisdiction) to density bonuses for projects that incorporate more affordable units. Local governments are also free to enact their own additional policies to boost affordable housing.

These and other policies may not help all tenants facing displacement, but they would go a long way toward helping many of them — and providing access to better homes for many of them in the process. And overall, new housing near transit will benefit residents of all income levels, including low-income. It will stabilize home prices to allow more residents to live near jobs and save on transportation costs from avoiding long commutes. It will improve public health by reducing regional driving miles. It will provide high-wage construction jobs. It will reduce economic inequality and lack of access to good jobs. And it will unlock the housing that future generations will need to be able to remain in their home communities.

Ultimately, we know we need new housing in California — and lots of it to make up for decades of shortfalls. We should have policies in place to ensure low-income renters gain from this construction. But if we don’t build these homes near our transit- and job-rich areas, then where are we going to build them? SB 827 provides the clearest solution to this decades-long problem in the making. But policy makers should take care to address the concerns of low-income renters who might otherwise stand to lose under this otherwise badly needed legislation.

As I blogged yesterday, the proposed SB 827 is the first truly revolutionary approach to boosting housing in the most environmentally and economically friendly places in California.

As I blogged yesterday, the proposed SB 827 is the first truly revolutionary approach to boosting housing in the most environmentally and economically friendly places in California.

And this morning on Southern California’s KPCC radio program Airtalk, I discussed the bill with host Larry Mantle, Los Angeles City Councilmember Paul Koretz (5th District), and Mark Ryavec, president of the Venice Stakeholders Association.

The 30-minute discussion surfaced most of the predictable yet flawed objections to the bill, typically raised by homeowners and their allies:

- These new residents in housing near transit won’t really ride the transit, they’ll just add to the local congestion. Mostly false: proximity to transit is a major determinant of how likely people are to ride it. However, it is true that lower-income residents are more likely to ride. But even locating middle-income residents near transit is still better than locating them far out of the city, where they’d have long drives leading to more overall traffic and pollution, or encouraging them to gentrify existing neighborhoods due to the lack of new housing supply. And as we’ve seen in urban areas like the San Francisco Bay Area and Washington DC, professionals will ride transit if it’s convenient to their work.

- New housing near transit will only add to parking and traffic congestion in my neighborhood. Yes, possibly in the immediate areas. But if the new developments don’t oversupply and under-price parking (and SB 827 relaxes minimum parking requirements) and instead offer better transit, walking and biking access, people will be more likely to choose to avoid the traffic. And overall traffic across the region will decrease with more in-town housing, which means less pollution and regional congestion for everyone. Otherwise, the alternative is more sprawl housing.

- Transit isn’t functional in L.A. right now, so there’s no need to build more housing near it. This is to some extent a circular argument. If there’s not sufficient housing (or other development) near transit, then as a result it won’t serve many of the places people want to go. Only by encouraging that development near rail and other high-quality transit — as opposed to waiting decades for rail to go to the right places — can the system be successful. We see this all around the world with well-functioning transit lines.

The discussion and listener comments are worth hearing, because they track the typical objections to the bill’s proposals. As I wrote yesterday, SB 827 will be a huge political effort. But at the same time, it presents an opportunity to discuss the facts with the persuadable part of the electorate.

California State Senator Scott Wiener just introduced the bill I’ve probably been waiting for since I started following land use and transit in California. SB 827 would dramatically scale back local government restrictions on housing near major transit stops (see the fact sheet PDF).

These restrictions by local governments have prevented new housing from being built in precisely the job- and transit-rich locations where we need housing the most. They’ve also prevented transit from performing well, in terms of greater ridership and reduced public subsidies, as light rail lines like Expo in Los Angeles serve neighborhoods that don’t allow anything but a single-family, detached home to be built.

Overall, the effect on housing supply from these exclusionary zoning policies has caused severe environmental degradation in the state by encouraging more sprawl and traffic. And it’s caused an economic crisis of unaffordable homes and rents that has squeezed the middle class right out of the state and led to gentrification of low-income neighborhoods.

SB 827 puts a bullseye on these policies. First, among other reforms, it would remove all density limits and parking requirements on any project within a half-mile of a major transit station, defined as anything from rail to a bus stop with at least 15 minute intervals during peak commute times.

As if these changes aren’t enough, SB 827 would prevent local governments from imposing a height limit of less than 85 feet if the development is within one-quarter mile of a “high-quality transit corridor” or within one block of a major transit stop (with a few exceptions), and 55 feet if within a half-mile.

As Sen. Wiener explained in a Medium post:

California has a number of communities with strong access to transit, and we continue to invest in public transportation. Too often, however, the areas around transit lines and stops are zoned at very low densities, even limiting housing to single family homes around major transit hubs like BART, Caltrain, Muni, and LA Metro stations.

Mandating low-density housing around transit make no sense.

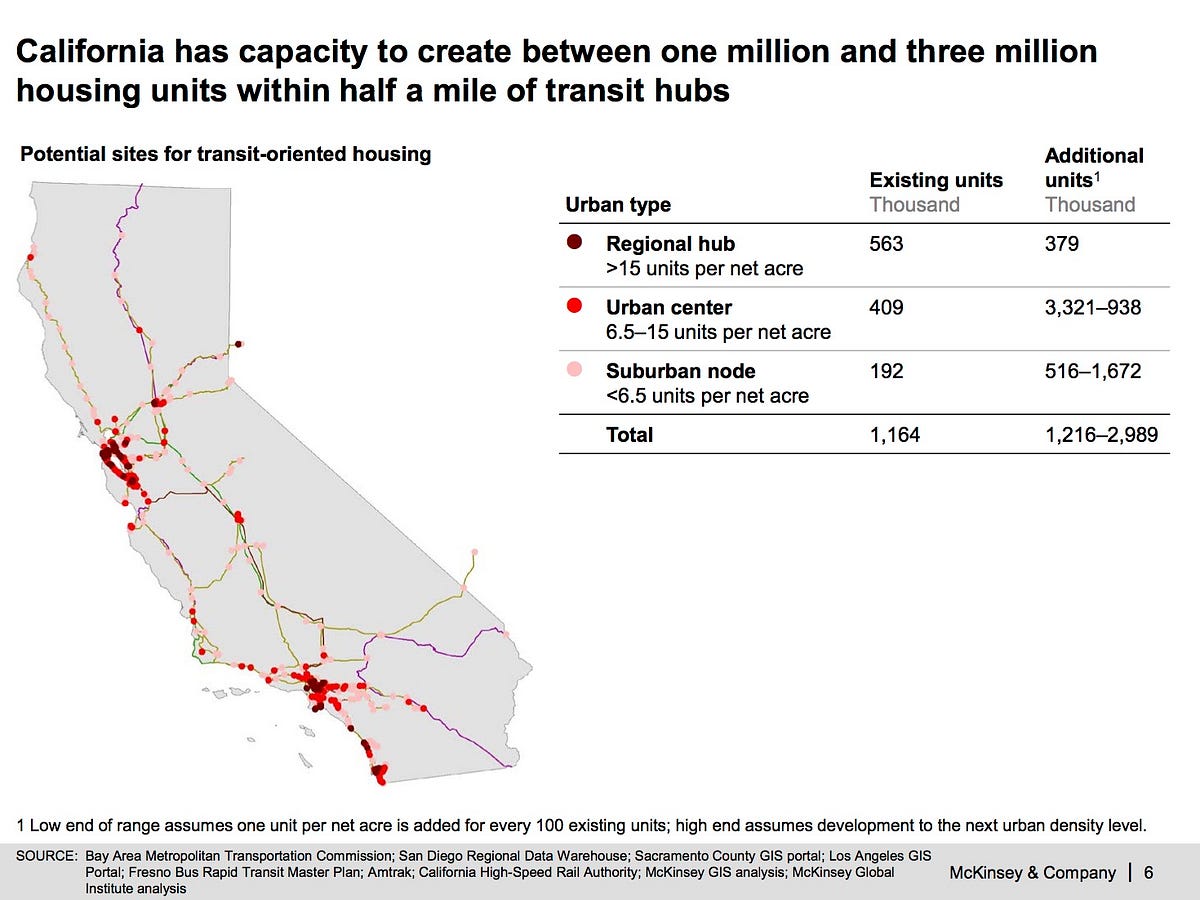

Sen. Wiener went on to cite a recent California analysis by the consulting firm McKinsey, which concluded that California could build up to three million new transit-accessible homes in these transit-rich areas:

Along these lines, our analysis at CLEE and UC Berkeley’s Terner Center in the 2017 report Right Type, Right Place found that California could achieve annual greenhouse gas reductions of 1.79 million metric tons if we built all new residential development within a few miles of major transit (not to mention additional savings if you factor in new commercial development in those areas plus reduced driving and pollution from existing residents there).

California has attempted to address this environmental and economic challenge from the multi-decade long underproduction of housing legislatively over the past few years. But most of those bills have been largely ineffectual reforms to planning or way-too-limited streamlining that only adds up to a drop in the bucket. Meanwhile, even relatively robust efforts to subsidize affordable housing are miniscule compared to the scope of the problem. SB 827 is the first one that could really, truly be a game-changer for housing and the environment.

To be sure, SB 827 faces an uphill battle to passage. Wealthy homeowners in single-family neighborhoods, along with their elected representatives and lobbyists, will be out in full force to defeat this bill. They may even have help from advocates of subsidized affordable housing, who often rely on processes to relax these exclusionary local policies as a way to gain concessions to build more affordable units. The parking requirement relaxation provision alone was already attempted back in 2011 as a standalone bill and went down to defeat in the legislature at the hands of the League of California Cities.

But on the upside, the politics in Sacramento around housing have changed in the past few years, as the scale of the problem has become more clear and as constituent groups like the “YIMBYs” have been organizing politically. That means that the bill may eventually survive to passage, albeit in a potentially stripped-down form.

If it goes down to defeat, it will be interesting to see how much support it gets. Because this issue isn’t going away, and neither are pro-housing advocates. They’ll keep coming back until California starts to take steps to address decades of terrible land use policies.

SB 827, as introduced, is the first truly significant step in that direction.

Transit advocates never really liked Elon Musk anyway. The billionaire entrepreneur behind Tesla has almost single-handedly made electric vehicles cool and desirable. But as I’ve blogged before, the cleaner cars become, the more that progress undermines one of the crucial arguments in favor of transit: that it can reduce air pollution as an alternative to dirty cars. On top of that, many transit advocates simply hate cars. So the idea that cars can now be an environmental “good” (or at least dramatically less bad for air pollution) is hard to stomach (of course, electric vehicles also include buses).

Transit advocates never really liked Elon Musk anyway. The billionaire entrepreneur behind Tesla has almost single-handedly made electric vehicles cool and desirable. But as I’ve blogged before, the cleaner cars become, the more that progress undermines one of the crucial arguments in favor of transit: that it can reduce air pollution as an alternative to dirty cars. On top of that, many transit advocates simply hate cars. So the idea that cars can now be an environmental “good” (or at least dramatically less bad for air pollution) is hard to stomach (of course, electric vehicles also include buses).

The resentment has popped up numerous times on social media and pro-transit articles, particularly around Musk’s plan for tunneling underneath Los Angeles. The plan seems to mimic existing publicly funded rail transit lines, as Curbed LA described. But instead of transit, the tunnels would feature private vehicles and larger shuttles with “between 8 and 16 passengers” that would ferry through the tunnels on sled-like “electric skates” up to 150 miles per hour.

Transit advocates largely found the vehicle-focused proposal threatening and referred to it as a waste of money that will not solve congestion and likely only induce more of it. They also noted it conveniently serves Musk’s house and office, insinuating that he’s building it to enrich himself.

The tension then boiled over when Musk recently went on a rant against transit:

“There is this premise that good things must be somehow painful. I think public transport is painful. It sucks. Why do you want to get on something with a lot of other people, that doesn’t leave where you want it to leave, doesn’t start where you want it to start, doesn’t end where you want it to end? And it doesn’t go all the time. It’s a pain in the ass. That’s why everyone doesn’t like it. And there’s like a bunch of random strangers, one of who might be a serial killer, OK, great. And so that’s why people like individualized transport, that goes where you want, when you want.”

Transit consultant and persistent Musk critic Jarrett Walker attacked in kind:

In cities, @elonmusk‘s hatred of sharing space with strangers is a luxury (or pathology) that only the rich can afford. Letting him design cities is the essence of elite projection. https://t.co/gtSVgPkfPo https://t.co/CmCpoIJ5NE

— Jarrett Walker (@humantransit) December 14, 2017

Musk responded on Twitter by calling Walker a “sanctimonious idiot.” Transit advocates in turn had Walker’s back, questioning whether Musk is an “elitist jerk” and generally amping up criticism of his urban mobility vision.

For my part, I question why transit advocates feel so threatened by Musk’s tunneling plans. First and foremost, at this point it doesn’t involve any public dollars. If Musk wants to spend his own money on an ultimately doomed plan to reduce traffic, then what’s the harm to the public? And if he’s successful, why would it be any more of a threat to transit than the current regime of publicly funded roads and highways? And isn’t there the possibility that his work could lead to innovations in tunneling and transport that might actually benefit transit and related development?

I’d also note that it’s somewhat unclear what Musk truly intends with these tunnels. They might end up being more practical for Musk’s beloved “hyperloop” idea, which in turn might be better suited for goods movement rather than people movement, given the potential danger and risk of nausea in the tubes.

Finally, I think it’s worth acknowledging that while Musk’s comments about public transit are inaccurate (not ‘everyone’ hates riding transit), he speaks for a large percentage of people, like it or not. Check out Eric Jaffe’s article on the subject from a few years ago:

Every transit advocate knows this timeless Onion headline: “98 Percent Of U.S. Commuters Favor Public Transportation For Others.” But the underlying truth that makes this line so funny also makes it a little concerning: enthusiasm for public transportation far, far outweighs the actual use of it. Last week, for instance, the American Public Transportation Association reported that 74 percent of people support more mass transit spending. But only 5 percent of commuters travel by mass transit. This support, in other words, is largely for others.

Public transit, particularly buses, do not poll well or have a very positive image among vast segments of the public, as I’m guessing a transit consultant like Walker knows. The recent nationwide ridership dip proves the point to some extent, as former transit riders are now choosing more convenient options like Uber and Lyft (or purchasing a vehicle or driving one more frequently).

For multiple reasons, we should all want public transit to succeed: it can foster more sustainable, transit-oriented development, it can provide people of all incomes with car-free travel options and therefore reduce pollution and sprawl, and it can enhance quality of life by supporting dynamic, equitable, community-oriented neighborhoods.

But many people have a negative view of transit, and not without good reason. Musk not only speaks for them, he’s speaking to them. And as long as that public attitude and its underlying causes persist, attacking Musk is at best a waste of time and at worst a failure to address some core challenges facing transit.

Republicans from the House and Senate last week unveiled their compromise conference tax bill. Due to intense lobbying efforts, Republican negotiators seem to have reduced some of the harm I described for renewable energy, electric vehicles, and affordable housing. As Brad Plumer in the New York Times writes, support for renewables is now bipartisan, as Republican states like Iowa produce a lot of wind power, while states like Ohio and Nevada with Republican senators manufacture a lot of clean technology equipment.

Republicans from the House and Senate last week unveiled their compromise conference tax bill. Due to intense lobbying efforts, Republican negotiators seem to have reduced some of the harm I described for renewable energy, electric vehicles, and affordable housing. As Brad Plumer in the New York Times writes, support for renewables is now bipartisan, as Republican states like Iowa produce a lot of wind power, while states like Ohio and Nevada with Republican senators manufacture a lot of clean technology equipment.

Most of the changes in the bill involve corporate tax credits, which are used to finance renewables and affordable housing. First, the conference bill removes the corporate “alternative minimum tax,” which would have made tax credits essentially moot with corporations unable to reduce their taxes below a certain amount. Second, it minimizes the damage from a new provision called the Base Erosion Anti-Abuse Tax (BEAT), which seeks to prevent multinational companies from claiming a portion of production or investment credits. The conference bill allows the credits to offset up to 80 percent of the BEAT tax, which helps preserve the market for the credits among multinational companies (Utility Dive offers a good overview of the details of these provisions).

Wind power is still hurt by the bill, given that the new provisions do not cover the full duration of production tax credits that finance these projects. And by reducing corporate tax rates overall, the bill decreases corporate “tax appetite” that helps drive demand for the tax credits. But it could have been much worse.

Meanwhile, the conference bill continues the tax credit for electric vehicle purchases, which is set to phase out for each automaker anyway based on sales (but the bill reduces tax incentives for transit and biking). This credit has been very important to boosting demand, as University of California, Davis transportation researchers have documented.

Finally, on affordable housing and other infill projects, the draft legislation would preserve most of the tax credits used to finance these projects. It retains the low-income housing tax credits (LIHTC), continues tax-exempt private activity bonds, including multifamily bonds, which are used to finance all sorts of infill infrastructure, and saves the 20% historic tax credits. It also retains new markets tax credits and of course reduces the corporate tax rate to 21%, which presumably benefits many infill developers. You can read more on the provisions affecting housing and land use from Smart Growth America.

Presuming no new issues arise, votes on the compromise bill could come this week and possibly be signed into law before Christmas. Overall, it’s a bill that will add at least $1.5 trillion to the debt, starve government of funds to provide basic services and infrastructure, and mostly benefit the wealthy and large corporations at the expense of middle-income earners.

But for clean technology and housing at least, it went from devastating to just bad.