Transit ridership is declining nationwide, while driving miles are up. Recent research indicates that increased access to vehicles by lower-income residents is particularly responsible for the transit dip, as lower-income residents tend to ride transit more than higher-income earners. And land use policies that encourage or force low-income residents to move far from jobs may be a determining factor.

First off, as Governing reports, poor people are increasingly able to access vehicles:

Only 20 percent of adults living in poverty in 2016 reported that they had no access to a vehicle. That’s down from 22 percent in 2006, according to a Governing analysis of U.S. Census data. Meanwhile, the access rates among all Americans was virtually the same (6.6 percent) between those two years.

In addition, lower-income earners are now able to get easy access to car loan services, including “subprime” auto loans.

But while economic factors play a role, so does land use:

“The country is becoming more car-oriented, because the country is moving south. If you’re moving from transit-oriented cities in the Northeast and moving to Texas, you’re going to become more car-oriented,” [urban planner and transportation consultant Sarah Jo Peterson] says.

Urban planners who want to push for walkable neighborhoods and transit-oriented development can still make a compelling case for certain areas, particularly urban centers, she says. “What they don’t have is wind at their backs.”

This migration of poor families to the suburbs, where housing is cheaper but transit service is weak, requires them to purchase an automobile to get access to jobs.

In Los Angeles, the Southern California Association of Governments commissioned a study by UCLA researchers on the causes of the ridership decline. The numbers from the report [PDF] are striking in terms of how concentrated transit ridership is in L.A.:

Ten percent of all of the people who commuted to and from work on transit in 2015 lived in 1.4 percent of the region’s census tracts, which covered just 0.2 percent of the region’s land area; the average number of transit commuters in these few tracts was almost 12 times the regional average. Fully 60 percent of the region’s transit commuters lived in 21 percent of the region’s census tracts, which occupied 0.9 percent of the region’s land area. Overall, the most urban and transit-friendly neighborhoods in the SCAG region comprise less than one percent of the region’s land area.

Areas that were heavily populated with transit commuters in the year 2000 became, in the next 15 years, slightly less poor, and significantly less foreign born. Perhaps most important, the share of households without vehicles in these neighborhoods fell notably. All these factors align with a narrative where a transit-using populace is replaced by people who are more likely to drive.

So while researchers are still analyzing the various causes for the ridership decline, the fact that low-income residents are moving to exurban areas may be a prime reason. And that displacement is likely due to high housing costs and gentrification in our prime transit areas. Until we solve that problem, we may not be able to resuscitate the nation’s transit systems anytime soon.

The killing of SB 827 in committee on Tuesday received a lot of media attention, which hopefully furthers this important dialogue. Here are some noteworthy pieces:

San Jose Mercury News: Why did California’s major housing bill fail so quickly?:

The proposal was not the typical stuff of wonky housing policy. A new analysis by the data firm UrbanFootprint found that if every parcel of land along the 45-mile El Camino Real corridor was redeveloped according to the new height limits allowed under SB 827, the number of homes along the route — from San Bruno to San Jose — would triple to 453,000.

But it also found that a potentially less contentious alternative, adding homes to commercial developments along the same corridor, would nearly double the housing stock.

E&E News: Plan to build housing — and cut CO2 — fails in Legislature:

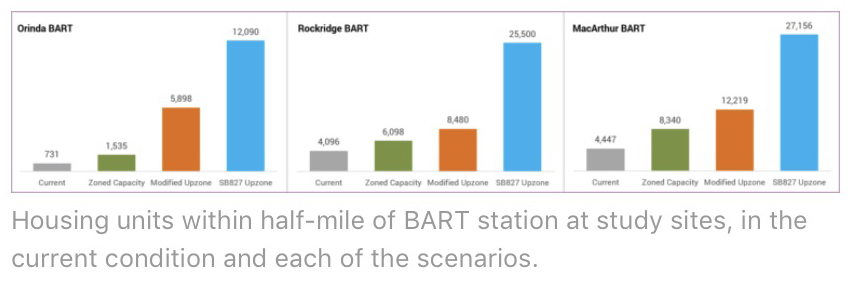

Other housing bills this session that are still moving include Wiener’s S.B. 828, to tighten regional planning requirements for affordable housing, and S.B. 829, which would streamline permitting for farmworker housing. Another that environmentalists are watching is A.B. 2923, which would require the Bay Area Rapid Transit system and local jurisdictions to up zone land within a half-mile of station entrances.

San Francisco Chronicle: Yelp CEO calls on Google, Facebook to help housing crisis:

Wiener vowed to bring it back next year. He wouldn’t say in what form, except that “I don’t believe the bill should be further scaled back in terms of density and geography.”

KPCC AirTalk: Senator behind California’s most ambitious housing bill debriefs on its defeat in committee

Interestingly, Sen. Wiener describes in this interview how he was really just one vote short in committee, as one of the “no” votes would have favored it if the votes were otherwise there to pass it.

New York Magazine (Jonathan Chait): The Urban Housing Crisis Is a Test for Progressive Politics:

“The zoning crisis is ultimately a question of whether the most prosperous parts of blue America can be opened up to new entrants, or whether they will remain closed off and increasingly unaffordable.”

Gimmme Shelter housing podcast with Matt Levin and Liam Dillon:

Yesterday afternoon, SB 827 was killed in its first committee. Though a number of legislators acknowledged California’s severe housing shortage, few were willing to risk the political backlash of taking on the local government lobby.

The bill needed 7 votes on the 13-member Senate Transportation and Housing Committee but only got 4. Here were the votes in favor, from the San Francisco Chronicle tally:

- Sen. Ted Gaines, R-El Dorado Hills: Yes

- Sen. Mike Morrell, R-Rancho Cucamonga (San Bernardino County): Yes

- Sen. Nancy Skinner, D-Berkeley: Yes

- Sen. Scott Wiener, D-San Francisco: Yes

Notably, the bill pulled in two Republican representatives (Sen. Gaines and Morrell) from inland areas, as I suspected. Politically, they should have an interest in keeping displaced liberal voters from moving into their districts for super-commutes and cheaper housing. Meanwhile, Sen. Skinner was a bill co-author and Sen. Wiener of course authored the bill.

Then the “no” votes:

- Sen. Jim Beall, D-San Jose (chair): No

- Sen. Anthony Cannella, R-Ceres (Stanislaus County) (vice chair): No

- Sen. Benjamin Allen, D-Santa Monica: No

- Sen. Bill Dodd, D-Napa: No

- Sen. Mike McGuire, D-Healdsburg: No

Most of these senators represent upscale areas with affluent homeowners. Most are Democrats. Surprisingly, Republican Sen. Cannella voted against it, even though the bill only affected 2.4 square miles (or 0.0%) of his entire district. Sen. McGuire and Dodd’s districts were also barely affected by the legislation. Notably, Sen. Allen represents transit-rich Santa Monica, a predominantly wealthy homeowner enclave, while Sen. Beall represents some exclusive neighborhoods in the San Jose area.

And for reasons that are unclear to me, these senators did not vote:

- Sen. Cathleen Galgiani, D-Stockton: Not voting

- Sen. Richard Roth, D-Riverside: Not voting

- Sen. Andy Vidak, R-Hanford (Kings County): Not voting

- Sen. Bob Wieckowski, D-Fremont: Not voting

Given these votes, it’s clear SB 827 has a long way to go (politically speaking) to convince state legislators that even a relatively modest check on local zoning authority to allow more housing near transit is needed.

The fallout from the vote should be obvious. Any hope for big sweeping changes in local restrictions on homebuilding will not happen anytime soon. I’m sure businesses around the state and country have taken note, when it comes to deciding whether to stay in California or locate a new business here. The message from the legislature is now clear: California is not serious about solving its housing shortage anytime soon.

And it’s a tough message for those struggling to pay rent or start a life here. It was always going to take years to repair the damage from decades of under-building homes in the state. And now we’re delayed yet another year or longer from getting going on real solutions.

The displacement problem will also worsen. Despite opposition from tenants rights groups, SB 827 was their best hope at addressing the root causes. The bill would have helped reduce regional housing shortages that push wealthier residents to buy up existing units in the absence of new ones, and, as this letter from noted fair housing experts explains, it would have helped open up wealthier, racially homogeneous enclaves to more diverse residents. Instead, tenants rights groups focused on boosting rent control as a solution. But this policy is really just a last-ditch effort to protect the dwindling low-income renters left in our cities, hanging on against the tide of gentrification unleashed by the regional housing shortage.

The result is the further exodus from the state of middle class residents, as well as the displacement to the fringe of our megacities of our working class residents. From these exurban areas, they’ll continue “super-commuting” into job-rich city centers, spewing air pollution from their cars, congesting our freeways, and sprawling out in cheap housing over former farmland and open space.

And this isn’t some dystopian future. This dynamic is already happening right now. The failure of SB 827 just means we’ve locked this future into place for years to come.

So what is the path forward? Big reform is likely dead. Incrementalism will replace it. But the basic approach shouldn’t change, because the problem (housing shortages with high demand) and its cause (local government restrictions on housing) will persist.

Here are some options:

- Focus an SB 827-type approach on allowing more housing on commercial and mixed-use zones near transit. Since these lands are commercial in nature, there won’t be any concerns about displacement of existing residents. Think redevelopment of strip malls and parking lots to allow housing and mixed-use development as the highest and best use.

- Narrow the scope of SB 827 to major rail transit stops only. The original bill included high-quality bus stops, which greatly expanded the geography of the bill, thus expanding an opponent base of hostile local governments. Conceivably, a narrower scope might help the chances of passage (although the “no” votes of representatives with almost no land affected by the bill in their districts should provide some caution on this point).

- Move forward incrementally with parking and density relaxations near transit. The bill originally included these provisions but also allowed higher height limits. Neighbors tend to react most reflexively against taller buildings, in my experience. A focus on parking and density may be less controversial (although previous efforts to deregulate local parking requirements failed, so this would by no means be an easy lift).

I’m sure other ideas will come forward in the days and months ahead. Pro-housing advocates will only grow in rank and intensity as the housing affordability problem worsens, and they’ll be back with new proposals. The setback yesterday was decisive but temporary.

Credit is due to Sen. Wiener and the co-authors: they have finally gotten Californians to focus on the true source of the housing problem. And the first step to solving any problem is identifying its cause. With all the national attention and conversation, SB 827 certainly accomplished that goal.

SB 827, to relax local restrictions on home-building near transit, faces a big test this afternoon at its first Capitol committee hearing. As the hearing draws near, it’s worth noting how disappointing the reaction to the bill has been from some advocacy groups that are supposedly in the pro-climate and transit worlds.

Scott Lucas at San Francisco Magazine has a lengthy piece exploring one of those groups’ opposition to the bill: the Sierra Club California. The article features this exchange with the head of the organization:

Although [Sierra Club California director Kathryn] Phillips says she supports infill development around mass transit, it’s hard for her to locate an actual place in California where she supports new buildings. This is also true of the Bay Area chapter, which in recent years has opposed the 8 Washington condo tower near the Embarcadero, the redevelopment of Treasure Island and the Hunters Point Shipyard, the expansion of Park Merced, and the new Golden State Warriors stadium. Recently, the chapter opposed a 66-unit development in the Western Addition because it would replace an auto repair shop it deemed historic.

With regard to upzoning near transit, Phillips rules out Sacramento, where some neighborhoods, she thinks, would use upzoning as an excuse to block new transit, concealing what she calls “racist” reasons under a civilized veneer. Nor does she think it’s appropriate in more outlying areas like Folsom, where a transit stop under the bill would lead to an upzoning too near wilderness areas. She doesn’t think it’s a good idea in San Diego, where taller buildings would block views of the ocean, nor does she support it in major cities like Los Angeles or San Francisco, where “people who live in rent-controlled buildings worry about bigger and bigger buildings coming toward them.”

As she finishes enumerating those exceptions, she adds, echoing the national organization’s policy line, that “we see the value of infill higher-density development around transit.”

SB 827 has revealed a lot about the politics behind our current housing dysfunction in the state. We knew wealthy homeowners and their allies in office would oppose allowing more homes built in their transit-rich communities. But the bill has also pulled the curtain back on the hypocrisy, confusion and cowardice within much of the climate and transit advocacy community about how to deal with the massive housing shortage in the state.

If SB 827 is successful, it will unfortunately be in spite of many of these advocates. And that’s not a good sign, given how much work needs to be done to improve California’s land use policies in an era of climate change.

California can’t meet its long-term climate goals without reducing its overall driving miles, per a state analysis of greenhouse gas emissions through 2050. This point was echoed in a recent New York Times article on SB 827, the measure to lift local restrictions on transit-adjacent housing. In the Times piece, bill author State Senator Scott Wiener said:

We can have all the electric vehicles and solar panels in the world, but we won’t meet our climate goals without making it easier for people to live near where they work, and live near transit and drive less.

Wiener isn’t just making that claim up. According to the California Air Resources Board’s staff report on regional greenhouse gas emission reduction targets, the state will need a reduction in vehicle miles traveled (VMT) through 2035 and 2050, even with more zero-emission vehicles sold and renewable energy deployed. They have a simple chart showing the calculations:

Basically, if by 2035 half of all new cars sales are zero emission, with half of all electricity (and thus transportation fuels) coming from renewable sources, we will still need a 7.5% reduction in baseline VMT.

The good news is all that clean technology means there would be slightly less pressure to reduce driving miles. But as the staff report pointed out:

The GHG emissions reduction contribution from VMT is a comparatively smaller in share than the GHG emissions reductions called for by advances in technology and fuels, but necessary for GHG emissions reductions in other sectors such as upstream energy production facilities and natural and working lands, and are also anticipated to lead to important co-benefits such as improved public health.

My one critique of the analysis is that it is conservative on the renewable mix by 2035. California has a statutory requirement to achieve 50% renewables by 2030, and we’re already over 35%. I would guess we’ll be at 60% renewables by 2030 and maybe 65% by 2035, not including greenhouse-gas free hydropower. In addition, bullish estimates of zero-emission vehicles could have the state at 75% battery electric vehicle sales by 2035.

Still, the point remains that VMT reductions are crucial. And worse, these VMT efforts could be badly undermined by autonomous vehicles, which could encourage more driving as people take advantage of having robot chauffeurs for every little errand and trip.

All of this analysis points to the need for much more housing production near transit and jobs — an outcome that SB 827 would directly promote. Because clean technology alone won’t be sufficient when it comes to reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

California State Senator Scott Wiener’s SB 827, to relax local restrictions on housing adjacent to transit, is a revolutionary step in the history of California land use. The initial version of the bill was clearly an opening salvo, reflecting a general statewide principle that locals should no longer squash housing in prime transit areas.

So it was inevitable that the legislative process would chip away at this broad framework, sometimes for good (recognizing that context matters in a state as large and diverse as California and that some changes might actually improve implementation and achievement of the larger goals) — and sometimes for bad (appeasing key legislators who don’t care much about building new housing near transit, to get their votes).

And now the first significant round of amendments were just introduced last night as the bill faces its first committee hearing and vote, with the promise of potentially another dozen rounds of amendments as SB 827 works its way through Capitol hearing rooms.

Below is the rundown on amendments, as Senator Wiener outlined in an accompanying Medium post. I’ll start with the good (or at least not horrible) and end with the unfortunate.

Good or Harmless Amendments:

- No net loss of affordable or rent-controlled housing provision: if a developer seeks to use SB 827 to build on a site with rent-controlled or subsidized affordable housing, the developer must replace each of these units with a permanently affordable housing unit on a 1:1 basis. This is a good provision because a loss of low-income residents near transit is not only unfortunate for those residents, it undermines transit usage. Low-income residents tend to use transit more than upper-income people. So we don’t want a situation where 30 low-income residents are replaced by 30 affluent residents under the bill. Otherwise, there could be a net loss in transit ridership and usage.

- Scale back qualifying bus stops: in its original form, SB 827 would apply equally to rail transit stops and any bus stop with 15-minute headways during commute hours. The provision might have been too generous, as many bus stops may have those headways during commute times but otherwise don’t provide enough service to truly allow car-free living for those nearby. The amendments now make the bill apply only to transit stops that have “consistent, high-quality transit during the week and on weekends, from early morning to late night.” Specifically, they must have at least 20 minute average service intervals between 6am and 10pm and 30 minute intervals on weekends from 8am to 10pm. The upside is that we won’t be building a lot of homes near transit stops that don’t really provide sufficient service to allow car-free living (or at least significantly reduced car trips).

- New residential percentage thresholds: any project under SB 827 must now be at least two-thirds residential by square footage.

The Not Terrible Amendments:

- Restriction on demolitions: a developer could not use SB 827 to demolish a building if the properties have had an Ellis Act eviction (kicking rent-controlled people out of their units with legal justification) recorded in the last five years. This provision provides an additional disincentive for property owners to evict rent-controlled residents, beyond what’s already in the bill. As with the “no net loss” provision, it might reduce the chances of displacement of low-income residents.

- Scale back relaxation of parking minimums: high parking requirements are a major disincentive to more dense development and essentially a tax on all homebuyers and renters. One of my favorite parts of the bill was that it eliminated parking requirements for any project within .5 mile of transit. But the new amendments allow cities to impose a .5 parking spot requirement per new residential unit in the .25 to .5 mile zone around transit. A developer must also provide recurring monthly transit passes to all residents at no cost. I don’t love the scaling back of the parking provision, but .5 in this outer radius is still a win. It mirrors the big parking victory under AB 744 (Chau, 2015), sponsored by the Council of Infill Builders, which reduced parking minimums to .5 for all affordable housing projects near transit, including in the 0-.25 mile zone that SB 827 relaxes completely. I’ll file this change as “not terrible” for now, barring any future weakening.

The Unfortunate Amendments:

- Lower height restrictions: the original bill allowed construction up to 85 feet within .25 miles of transit, under certain conditions. Now, around rail and ferry stations, only buildings up to 55’ tall can be permitted in the first .25 mile and 45’ in the second .25 mile zone. Furthermore, no building height increase will take place around any qualifying bus lines. The one upside is that parking and density restrictions will still be relaxed. For me, reducing the height limits means fewer units will be built, which is too bad. But if I had to give on either density, parking or height, I would probably give up on height, among the three. Density relaxations can help make up for many of the lost units that would have been built in the upper stories.

- Requirements to include affordable housing: it was pretty clear that SB 827 would have to include some kind of affordable housing mandate to pass, and here it is. If a community does not have a local “inclusionary housing” requirement (i.e. mandate for any market-rate developer to include some affordable units), the amendments offer a detailed set of options for developers to comply, ranging from 20% inclusionary if it’s a 50+ unit building to 10% low income or 5% very low income for 10-25 units. I don’t like inclusionary zoning because it’s a tax on new homebuyers and renters and not an equitable way to fund affordable units. It also depresses home production. A more equitable way to build affordable housing is through property taxes or broad-based taxes or bonds. But as far as things go, this isn’t a horrible formula.

- Delay of implementation by 2 years: SB 827 was set to go into effect this coming January 1st, if it passes. Now the operative date is two years later on January 1, 2021. A local government can also apply for a one-time, one-year extension if they can “prove to the Housing and Community Development Department that they have made significant good-faith progress.” The argument in favor is that local governments will have more time to “conduct studies, update inclusionary housing ordinances, and adopt specific transit oriented development plans.” Cities also won’t be able to use the time though to reduce or eliminate residential zoning to avoid SB 827 requirements. I don’t like the delay for two reasons: first, we need to get going on new home building right away, and local compliance with SB 827 really shouldn’t be that complicated. Second, I worry this gives opponents time to figure out a counter-strategy, or at least delay other needed measures to boost housing under the guise of “let’s see what happens in 3 years when SB 827 is finally in effect.”

Overall, a half a loaf is better than no loaf, and SB 827 is still a no-doubt landmark bill, even with these changes. The big worry is what happens in future rounds as more legislators require appeasement for their votes. But advocates can cross that bridge when they come to it. The main thing at this point is ensuring that there are still bridges to cross, with a worthy bill. And these amendments keep that effort going with only some loss and even some gain.

The great California housing debate over SB 827 (Wiener) has mostly been depressing to witness. The bill would essentially upzone areas adjacent to major transit, leading to badly needed housing production mostly in our affluent and transit-rich areas that can support more expensive multifamily construction.

Riding to the rescue of anti-growth affluent communities have been various advocacy groups focused on or allied with low-income tenants. These advocates mistakenly assume that the upzoning will lead to a building boom in low-income areas and contribute to gentrification and displacement. In reality, the upzoning will encourage development in high-rent areas and reduce pressure on displacement and gentrification overall.

So it was somewhat refreshing to see an advocacy group actually engage with the substance of SB 827, rather than react ideologically against it. TransForm has been focused on bolstering smarter land use around transit since it originally formed as the awkwardly named Transportation and Land Use Coalition (TALC) over 20 years ago. SB 827 in many ways should be the organization’s dream bill, as it seeks to reverse the exclusionary, low-density housing policies that have created the environmental and economic mess that California now finds itself in.

But TransForm is not entirely pleased with the bill. Their concerns revolve around preventing displacement of low-income residents, adding more affordable housing, and engendering a backlash against infill. In a blog post, they recommend:

- Value capture to increase affordable housing stock, likely through a requirement that a certain percentage of homes built under the bill be affordable (scaled to the size of the project)

- Stronger, enforceable renter protections, such as through ensuring no net loss of affordable housing in transit station areas

- More inclusive conversations about potential improvements

- Greater sensitivity to local context, such as different height limits on different land use types

- Consider “Missing Middle” housing types for low-density neighborhoods, such as designs that get over 80 units per acre with 25- to 30-foot buildings

- Place a maximum unit size on developments to avoid vertical McMansions

- Refine criteria for transit capacity, with different requirements for zoning based on transit types — BART, light rail, bus rapid transit, ferry, etc.

- Ensuring traffic and climate benefits by avoiding traffic congestion through parking maximums, providing on-site transportation amenities for residents, and maximizing affordability

- A clearer understanding of the bill’s geography and impact

Some of their recommendations are relatively harmless, such as a more inclusive process (which is what the legislative process is usually all about anyway) and better mapping. Some seem likely to engender the backlash they fear, such as parking maximums. And some seem overly fear-based, such as the need to “protect” single-family home neighborhoods to avoid a backlash — as if there isn’t already a big backlash against any new development.

In particular, it’s worth looking at differentiating land use requirements in the bill based on transit capacity, as well as increasing the enforceability of anti-displacement measures.

But TransForm should acknowledge that efforts to require more affordable housing through inclusionary zoning, even just in upscale areas, are essentially a tax on new housing to pay for more affordable units. This tax will depress housing production overall and put the burden of subsidizing affordable housing on new home buyers, rather than on existing homeowners who benefit from the status quo. Density bonuses would make more sense to boost affordable housing supply, as well as funding these units through increased taxes on current homeowners.

Still, it’s nice to see some substantive critiques from a land use advocacy group, particularly given how unproductive the nonprofit sector has generally been when it comes to finding actual solutions to the housing shortage. We’ll have to stay tuned to see if any of these recommendations make it into the bill.

I’ll be on KQED radio’s Forum this morning at 10am discussing SB 827 (Wiener) to relax local restrictions on transit-oriented housing. We’ll discuss what the bill might mean for California’s cities, environment and economy.

Please tune in at 88.5 FM in the San Francisco Bay Area and weigh in with your questions. Even if you don’t live in the Bay Area, you can stream it live.

We know that city dwellers have a smaller carbon footprint that suburbanites. But now we have a real case study with carbon measurements to document the phenomenon.

14 scientists at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, the University of Utah and several other universities set up a network of carbon dioxide sensors across Salt Lake City and its suburbs. The Washington Post reported on the results:

As suburbs have expanded southwest of Salt Lake City over the last 10 years, carbon dioxide emissions have spiked…

It’s the latest indication that suburban expansion takes an environmental toll, with people driving greater distances and building larger homes that use more energy for heating and cooling.

Similar population growth in the center of Salt Lake City didn’t take the same toll, according to the research. Carbon dioxide emissions in the city center were already higher than in nonurban places. But as the population there grew by 10,000 people, the emissions didn’t increase further.

It’s yet more evidence that encouraging urban growth is one of the most important steps we can take to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. And it’s also a reason why supposedly “environmental” organizations like Sierra Club California that oppose pro-infill measures like SB 827 are actually damaging the environment by doing so.