California law now requires developers of new projects, like apartment buildings, offices, and roads, to reduce the amount of overall driving miles the projects generate. Senate Bill 743 (Steinberg, 2013) authorized this change in the method of analyzing transportation impacts under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), from auto delay to vehicle miles traveled (VMT).

California law now requires developers of new projects, like apartment buildings, offices, and roads, to reduce the amount of overall driving miles the projects generate. Senate Bill 743 (Steinberg, 2013) authorized this change in the method of analyzing transportation impacts under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), from auto delay to vehicle miles traveled (VMT).

In response to SB 743, some state and local leaders are seeking to create special “banks” or “exchanges” to allow developers to fund off-site projects that reduce VMT, such as new bike lanes, transit, and busways. These options could be useful when the developers lack sufficient on-site mitigation options.

A new report from Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE), Implementing SB 743, provides a comprehensive review of key legal and policy considerations for local and regional agencies tasked with crafting these innovative mechanisms, including:

- Legal requirements under CEQA and Constitutional case law;

- Criteria for mitigation project selection and prioritization;

- Methods to verify VMT mitigation and “additionality”; and

- Measures to ensure equitable distribution of projects.

The report recommends that decision makers launching new VMT banks and exchanges consider including:

- Measures to verify the legitimacy of claimed VMT reductions, as well as their “additionality”;

- Prioritization of individual mitigation projects, in order to ensure that reductions are achieved as quickly and efficiently;

- Rigorous backstops to ensure that disadvantaged communities are not negatively impacted by—and ideally can benefit from—the ability of developers to move mitigation off-site; and

- Demonstration of both a reasonable substantive relationship and financial proportionality between the proposed development and the fee or condition placed on it.

Ultimately, SB 743 implementation will require a range of approaches from jurisdictions of varying sizes, densities, and development patterns throughout California. Local, regional, or even statewide mechanisms may evolve as mitigation programs mature and potential efficiencies are identified. Implementing SB 743 offers a guidebook to agencies and developers navigating the law’s new approach.

For more information, join CLEE’s webinar on Tuesday, October 30th from 10-11am with Governor’s Office of Planning and Research senior planner Chris Ganson and report co-author Ted Lamm and me. You can register for the free webinar today.

California’s legislature may have whiffed this year on SB 827, a comprehensive measure to boost housing near major transit stops this year. But state leaders ended up passing a significant and pioneering bill (now law, with Governor Brown’s signature on Sunday) that forces development on land owned by BART around its rail stations. It could be a precursor to future state efforts to limit local restrictions on development near transit.

AB 2923 (Chiu) requires the BART board to adopt new development standards for height, density, parking, and floor area ratios on land the agency owns within one-half mile of each of its stations. Local governments then have two years to conform their zoning with these standards — or else the standards become de facto land use policy.

AB 2923 (Chiu) requires the BART board to adopt new development standards for height, density, parking, and floor area ratios on land the agency owns within one-half mile of each of its stations. Local governments then have two years to conform their zoning with these standards — or else the standards become de facto land use policy.

The agency standards are limited to some extent, as height can only go as high as a certain percentage of surrounding buildings, and any net loss of parking for commuters has to be addressed through improved access. Furthermore, the parcels have to be owned by BART as of July 1, 2018, so BART can’t go on a buying spree to develop more land down the road.

So why was this law successful where the statewide SB 827 approach failed? Three reasons:

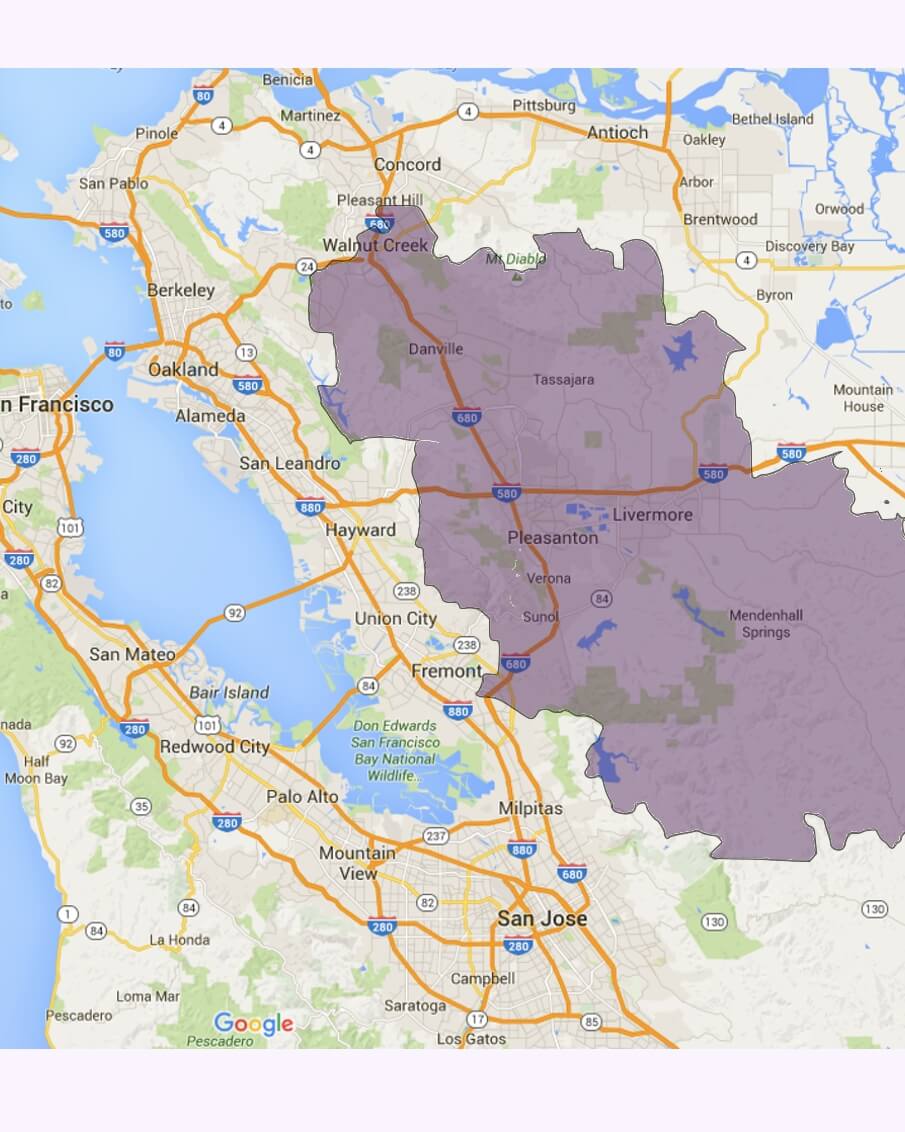

- AB 2923 covers a relatively tiny geographical area, just within the San Francisco Bay Area, thus minimizing potential opposition with a smaller scope (although suburban BART communities certainly freaked out to no avail); see map above;

- It includes mandatory affordable housing requirements for any new housing built under these standards, plus union workforce requirements, bringing two crucial constituencies on board to support it; and

- It only affects BART-owned land of primarily non-residential parking lots, which means there is no risk of displacing existing residents and raising the ire of groups dedicated to protecting low-income renters.

So what’s next? First, opponents are likely to sue to overturn the law, although I don’t think they’ll have a strong legal case given that other state-charted agencies have similar land use authority.

But more importantly, this legislation could encourage other California transit agencies in cities like Sacramento, Los Angeles and San Diego to request similar land use authority, broadening the scope of its application significantly. Furthermore, it could encourage the state to get more involved in limiting local regulation of land use near transit in general.

So while the legislature did not manage a comprehensive housing fix this term, it may have laid the conceptual foundation with AB 2923 for a new statewide approach to boosting housing near transit.

High housing costs are driven by two factors: increasing demand from a booming economy and lack of new supply to keep up. Now we have data that show how the rising costs are affecting low-income people of color the most in the greater San Francisco Bay Area.

UC Berkeley’s Urban Displacement Project and the California Housing Partnership document how rising housing costs between 2000 and 2015 have displaced these populations into new concentrations of poverty and racial segregation in the cheaper outskirts of the region, while prompting many to move out of the area altogether.

As an example from the study:

Between 2000 and 2015, as housing prices rose, the City of Richmond, the Bayview in San Francisco and flatlands areas of Oakland and Berkeley lost thousands of low-income black households. Meanwhile, increases in low-income black households during the same period were concentrated in cities and neighborhoods with lower housing prices—such as Antioch and Pittsburg in eastern Contra Costa County, as well parts of Hayward and the unincorporated communities of Ashland and Cherryland.

What can we do about these trends? Well, there’s little to do on the demand side, in terms of slowing the economy (which will happen during a business cycle downturn at some point anyway). Perhaps there are demand-suppressing options such as taxing vacant property or second homes at higher rates in the meantime. But there are no simple solutions.

So that leaves addressing the supply side, which means building more homes close to jobs (subsidies for affordable housing could help, too, but wouldn’t come close to meeting demand unless in the hundreds of billions dollars). And ironically the solution of building more infill homes is anathema to many advocates against displacement, who worry — sometimes rightly — that infill projects will displace existing low-income renters.

But by wholesale blocking solutions to more infill housing generally, such as SB 827 earlier this year, these same advocates are worsening the problem they care about, as the new data show. Unless we get a handle on high housing costs, the problem will only intensify.

It’s a conundrum that has to be addressed, if the state is ever to fix this economic, moral and environmental crisis brought on by the housing shortage.

As our political divide worsens into tribal camps, Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff argue in a New York Times op-ed that our isolated and over-supervised upbringing is to blame:

As our political divide worsens into tribal camps, Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff argue in a New York Times op-ed that our isolated and over-supervised upbringing is to blame:

But during the 1980s and 1990s, children became ever more supervised, and lost opportunities to learn to deal with risk and with one another. You can see the transformation by walking through almost any residential neighborhood. Gone is the “intricate sidewalk ballet” that the urbanist Jane Jacobs described in 1961 as she navigated around children playing in her Greenwich Village neighborhood. One of us lives in that same neighborhood today. His son, at the age of 9, was reluctant to go across the street to the supermarket on his own. “People look at me funny,” he said. “There are no other kids out there without a parent.”

The result of this isolation is in inability to get along with and respect others of different viewpoints. And it’s no accident that this time period in this research coincides with the rise of suburban sprawl — and the tremendous isolation it brings to children raised in that environment.

A suburban home with an enclosed backyard maximizes convenience for parents. They can supervise their kids outside without fear of strangers intruding or the kids running off, as they’re all safely penned in the backyard. A nice single-family home also provides a quiet respite for the working adult who commutes by car and can therefore the home leave whenever he or she wants for errands, socializing, and the like.

But for children, these backyards stifle the kind of random social interactions and independence that Haidt and Lukianoff cite as necessary for emotional development. And the car-dependent environment means the children lack self-sufficiency and mobility until they get their license and access to an automobile. They’re otherwise completely dependent on caregivers to ferry them around.

It’s yet another argument against the suburban sprawl model — beyond its unsustainable environmental impacts.

California has a poverty problem. Its poverty rate is by some measures the highest in the country. But while conservatives blame the state’s tax and social welfare structures, university researchers David Brady and Zachary Parolin pin the blame on high housing costs:

California has the highest supplemental poverty measure rate simply because of our highest-in-the-nation home prices. If housing prices in California were at the median seen across the rest of the United States, the state’s supplemental poverty measure rate would drop by nearly a third — to 11.7 percent from 17.1 percent. California would then rank 30th among the states based on 2015 data. This might not be surprising, as 29 percent of Californians spend more than half their monthly income to keep a roof over their heads.

High housing costs in this state are due to high demand, unmatched by available housing supply, particularly in our job-rich cities.

If Sacramento legislators really wanted to address poverty in the state, the single most important step they could take would be to increase housing production in these job centers to meet demand. Let’s hope the next legislative session brings some bold, meaningful solutions for this problem to the table.

The political battle over smarter land use development boils down to two sides: those like me in favor of development in existing neighborhoods to boost housing supply and limit sprawl and air pollution vs. those who protect the ‘character of their neighborhoods’ from any change. The latter are called NIMBYs — Not In My Backyard; the former are YIMBYs — Yes In My Backyard.

So what do I do when a song I like takes the NIMBY viewpoint? Death Cab For Cutie’s “Gold Rush” is explicitly about the sadness brought out by neighborhood change, with the title alluding to the profits made from redevelopment. Here’s the official “lyrics” video, complete with an infill construction site in the background:

Of course, there’s a strong metaphorical component to the song, about the ultimate disillusionment we’ll feel if we become too strongly attached to the present and to physical buildings to hold onto our memories and sense of identity.

But as much as I bash on NIMBYs as being selfish and sometimes racist, you’d have to be heartless not to respect the sadness that a resident can feel seeing the change in his or her neighborhood with redevelopment. It doesn’t mean that policy makers should always defer to those feelings, but more YIMBYs could also acknowledge the legitimate fear of (and sadness about) change in one’s hometown.

And perhaps while we’re at it, those on the NIMBY side who like to cite greed (“gold rush”) as the motivator for the YIMBY position could likewise acknowledge the legitimate concerns about poverty and the environment that underlie pro-redevelopment arguments.

A good song, after all, should help bring people of all persuasions together.

It’s not just Trump’s border taxes on solar panels that hurt the environment. The administration’s trade policies are now affecting residential infill construction, which we need to house a growing population in a sustainable manner, close to jobs and transit. As the Associated Press reports:

Trump’s tariffs on several categories of goods have prompted a trade war. Tariffs are currently just more than 20 percent on imported Canadian lumber and 25 percent on steel imported from some countries.

…

California Building Industry Association President Dan Dunmoyer said contractors tell him that the tariffs alone could add $8,000 to $10,000 to the lumber costs for a typical single-family home and about the same amount for steel products such as nails, other fasteners and wire mesh.Tariffs also are boosting the cost of appliances, drywall and solar panels, which will be required on all new homes in California starting in two years.

These border taxes make a bad situation for housing development even worse. UC Berkeley’s Terner Center is researching a report to analyze some of these economic challenges, including a dramatic labor shortage in residential construction:

All in all, together with labor shortages and bad local land use policies, these self-inflicted trade wars will significantly slow residential construction at a time when we need it the most.

San Francisco is about to open its new $2.2 billion Transbay Terminal in downtown, current home to transbay bus service and future home to Caltrain and high speed rail. I had an opportunity to tour the facility last week ahead of its big public opening on August 12th (photos below).

The new terminal replaces a 1930s era bus depot that used to receive San Francisco’s since-shuttered intercity electric trains coming off the lower deck of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge. But the eight-year construction project has been mired in controversy over the typical delays and budget-busting that you see with big new infrastructure projects. And it also has been blamed for contributing to the nearby Millennium tower sinking and shifting, based on the dewatering practices used to excavate the site.

My takeaway from the tour? It’s a beautiful building that will really help smooth bus transportation access to this growing neighborhood south of Market Street. And the other immediate benefit will be the rooftop park, which is reminiscent of Manhattan’s highly successful “high line” walkway.

But the long-term payoff will be if and when Caltrain and High Speed Rail begin service to its now empty basement level — though that may take more than a decade to come to fruition.

Below are some photos I took from above, within, and below the site.

First up, the view of the 5.4 acre rooftop garden from the Transbay Terminal project office:

Here’s a small-scale model displayed in the project office:

Here’s a small-scale model displayed in the project office:

Once inside the “Grand Hallway” of the terminal on the ground floor, the design team planned a mosaic floor covered in bright California poppies:

Once inside the “Grand Hallway” of the terminal on the ground floor, the design team planned a mosaic floor covered in bright California poppies:

In the basement, possibly the most hopeful yet depressing sight: where Caltrain and possibly high speed rail trains will arrive and depart (probably in the 2030s), serving downtown San Francisco with thousands of passengers each day (pending the funding to complete these multi-billion dollar projects):

On the second floor, you’ll find the new bus bridge from the terminal on that level, taking buses directly onto the Bay Bridge for service to the East Bay and beyond:

On the second floor, you’ll find the new bus bridge from the terminal on that level, taking buses directly onto the Bay Bridge for service to the East Bay and beyond:

And on the top floor, the aforementioned 5.4 acre rooftop park. Although it’s not as convenient to access as a street-level park, the concert series in this future bandstand and other activities should attract people, plus the nice views:

The half-mile bike- and scooter-free walkway around the top feels like a West Coast high line:

The park also features a fun access feature: a new gondola that will ferry people to the top from the street, hopefully in an efficient manner. The gondola won’t open until late August or early September:

Families with children will be welcome at this playground on the rooftop:

Overall, the terminal will be a real jewel for this part of San Francisco and a nice way to take transit. But it’s full potential won’t be realized until federal, state and local officials find the money first to extend Caltrain into it and then one day to bring in high speed rail to downtown San Francisco.

The Bay Area’s “Tri-Valley” region

High housing costs aren’t just pushing residents into far-flung exurbs in seek of affordable homes. Businesses, too, are locating far from city centers to take advantage of cheaper rents and lower housing costs for their employees.

The business groups Bay Area Council Economic Institute and Innovation Tri-Valley Leadership Group released a new report documenting the effect in the San Francisco Bay Area, as the San Francisco Chronicle reported:

The East Bay’s Tri-Valley region saw jobs grow 35 percent between 2006 and 2016, outpacing San Francisco and Silicon Valley, according to a new report.

During the same period, San Francisco had 31 percent job growth, Silicon Valley had 19 percent and California overall had 8 percent.

The Tri-Valley cities of Danville, Dublin, Livermore, Pleasanton and San Ramon benefited from the presence of two federal laboratories, along with less expensive housing and office costs compared to the Bay Area’s urban centers, the report said. At the same time, the Tri-Valley and the rest of the Bay Area continue grappling with low housing supply and traffic congestion.

Some of this dynamic is the natural progression of cities. As space in traditional city centers comes at a premium, employers seek to find more affordable regions in outlying areas.

But much of it is attributable to the failure of local governments in job-rich areas to allow enough housing to be built to keep pace with jobs. As a result, employers find themselves needing to go to outlying areas not just for cheaper office rents, but to meet middle class employees where they can find a relatively affordable home.

From an environmental perspective, this job sprawl means worsening traffic, air pollution, and paving over of valuable open space and agricultural land. Yet another reason to change our land use policies in job-rich urban centers to allow sufficient housing.

Due to work- and vacation-related travel most of this month, I plan to take June off from blogging.

In the meantime, some stories worth following on some of the issues I’ve been covering on this blog:

- Solar PV: Are the Trump solar tariffs actually bringing more solar manufacturing to the U.S.? Or does automation mean it’s just a different location for foreign-owned factories, as I originally suspected? Bloomberg reports.

- Electric vehicles:Tesla addressed Consumer Reports’ concern about braking distance on the new Model 3 with a pretty amazing over-the-air software update. Ars Technica thinks that’s good but also a bit troubling about the quality of the car’s braking system.

- Housing bills in California: SB 828 (Wiener) and AB 2923 (Chiu), two bills I’ve blogged about that will boost housing near transit, both passed their houses of origin. The Real Deal covers SB 828, and Greenbelt Alliance supports AB 2923.

See you in July!