As 2018 nears its end, here are my Top 6 developments in climate & energy policy this year:

-

- Worldwide greenhouse gas emissions increase. Let’s start with the bad news for 2018: emissions are rising like a “speeding freight train,” primarily due to more coal-fired power coming on line for India and China, plus more energy use in the United States. Emissions are expected to increase 2.7 percent in 2018, according to research published by the Global Carbon Project. Meanwhile, a U.N. report in October indicated that the world may have just about a dozen more years to get emissions under control enough to avert disastrous warming. These reports should be concerning to everyone.

- Solar PV hits policy and deployment bumps but with long-term growth potential. With declining policy support worldwide, including costly tariffs on solar PV in the U.S., solar PV leaders have seen a downturn in 2018, for the first time in recent memory. Globally, according to the Frost & Sullivan (F&S) report Global Renewable Energy Outlook, 2018, the world saw 90 gigawatts (GW) of new solar installations for 2018, which was a slight year-on-year decrease. Overall though, renewable capacity will see 13.3% annual growth in 2018. The report authors expect global investment in renewable energy for the year to be $228.3 billion, a slight increase of 0.7% over 2017. In the U.S., according to latest industry figures, the third quarter saw installed solar PV capacity experience a 15% year-over-year decrease and a 20% quarter-over-quarter decrease. However, total installed U.S. solar PV capacity is expected to more than double over the next five years. Overall, the picture is concerning but with a potentially positive long-term outlook.

- EV sales increase worldwide, with 1 million in the U.S. and the Tesla Model 3 finally unveiled. The chart below tells the largely encouraging story:

China leads the pack with 40% of all sales. Here in California, sales just reached half a million, with one million nationwide. Prices continue to fall, and the Tesla Model 3 became the #6 top-selling car in the U.S. in November. Of all the climate change news, this progress on vehicle electrification may be the most hopeful, although we’ll need to see even more rapid deployment over the next decade to get growing worldwide transportation emissions under control.

China leads the pack with 40% of all sales. Here in California, sales just reached half a million, with one million nationwide. Prices continue to fall, and the Tesla Model 3 became the #6 top-selling car in the U.S. in November. Of all the climate change news, this progress on vehicle electrification may be the most hopeful, although we’ll need to see even more rapid deployment over the next decade to get growing worldwide transportation emissions under control. - Electrification of transportation spreads to trucks, buses and scooters. The EV revolution has spread, with cheaper, more powerful batteries now making electric “micromobility” options feasible, such as e-bikes and e-scooters. 2018 was truly the year of the e-scooter, when it comes to city streets. And on the heavy-duty side, companies are unveiling previously unheard of electric models, such as Daimler Trucks North America making the first delivery of an all-electric delivery truck, the Freightliner eCascadia, while the California Air Resources Board last week enacted a new rule requiring transit buses to be all-electric by 2040. All told, it’s a positive development for low-carbon transportation.

- Movement to legalize apartments near transit in California and across the U.S. All the electrification we can muster on transportation won’t matter much if we don’t decrease overall driving miles. It’s a particular problem in the U.S., with so many of our major cities built around solo vehicle trips. So it was encouraging to see California attempt to legalize apartments near major transit with Scott Wiener’s failed SB 827 earlier this year (which started a productive conversation) and now a potentially viable version in SB 50. The movement is catching on around the country, as Minneapolis just voted to end single-family zoning. It’s long overdue and our only real hope to decrease driving miles.

- Trump rollback proposals increase but face judicial setbacks. Trump’s attack on environmental protections made news all year, particularly his attempted rollback of clean vehicle fuel economy standards. The only bright spot is that many of his regulatory rollbacks are sloppy and getting shot down in the courts, as my colleague Dan Farber noted in a report and recent Legal Planet post. And with Democrats set to control the House of Representatives next month, pro-environment legislators are set to have more negotiating power on everything from the budget to enforcement to policy oversight.

So the trends overall are uneven, with a lot for concern and also promising technology and policy momentum still in effect. 2019 could also greatly change this picture, with a potentially slowing economy and more private sector innovation on clean technology.

Overall, those who care about these issues have a lot to digest and ponder this holiday season, along with the cookies. See you in 2019!

The California housing debate took me to KQED-TV’s “Newsroom” program on Friday. You can watch my discussion with host Thuy Vu and State Sen. Scott Wiener, author of SB 50 to upzone areas near major transit, at the 18-minute mark:

This has been a relatively eventful year in California land use, given the state’s severe housing shortage, and I’ll be speaking about it this morning at the 14th Annual “CEQA Year In Review” Conference in San Francisco. The morning panel will cover “Streamlining CEQA for Housing Approvals.”

This has been a relatively eventful year in California land use, given the state’s severe housing shortage, and I’ll be speaking about it this morning at the 14th Annual “CEQA Year In Review” Conference in San Francisco. The morning panel will cover “Streamlining CEQA for Housing Approvals.”

I’ll cover the state’s relatively lackluster effort to date to streamline environmental review for infill housing projects, which has had limited success in allowing environmentally beneficial infill projects to avoid costly and time-consuming environmental review. And as my colleague Eric Biber has found, much of the problem traces to local government decisions to make approvals discretionary for larger projects, which automatically triggers the environmental review process.

I’ll also discuss potentially promising state-level effort to require upzoning around major transit, such as this past year’s AB 2923 to upzone BART-owned parcels as well as this coming session’s SB 50 debate. But even if the state can accomplish mandatory upzoning, locals will still try to stop new projects by instituting lengthy approval processes with multiple veto points. So the next phase in the battle to address the housing shortage will probably be to limit local permitting discretion over projects near major transit.

I look forward to the discussion and hope to see you at the conference today!

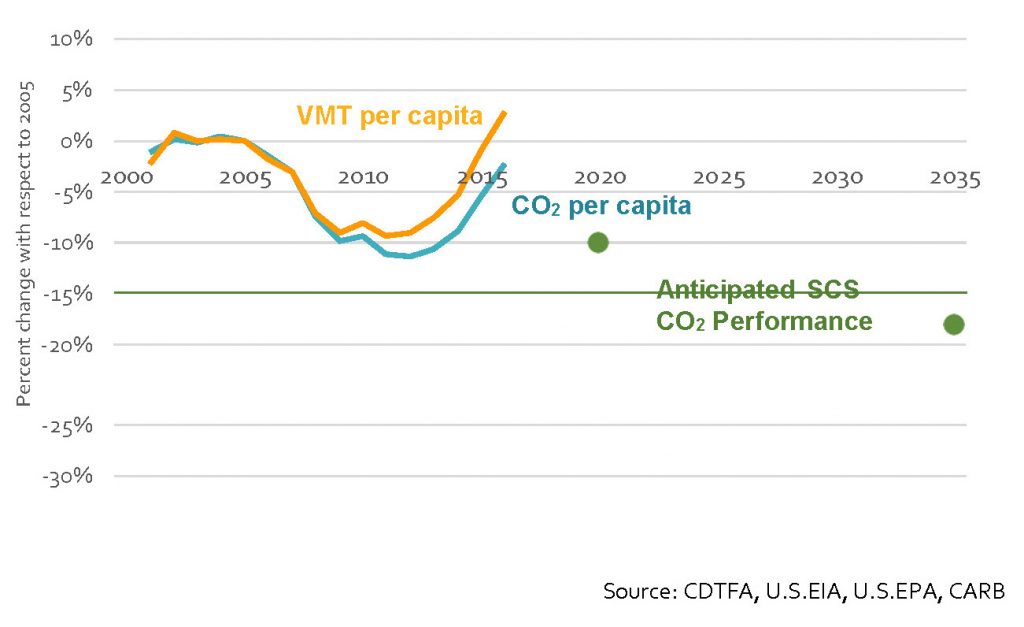

California’s major urban regions are falling behind in getting people out of their solo drives in favor of walking, biking, transit and carpooling, according to a major report last month from the California Air Resources Board. In short, the state will not meet its 2030 climate goals without more progress on reducing vehicle miles traveled (VMT):

This result comes despite the decade-old passage of SB 375 (Steinberg, 2008), which promised to reorient land use and transportation around reduced driving. The lone exception appears to be the San Francisco Bay Area, which has seen steadily increasing transit ridership and decreasing solo driving to work as a percentage, according to the report.

This result comes despite the decade-old passage of SB 375 (Steinberg, 2008), which promised to reorient land use and transportation around reduced driving. The lone exception appears to be the San Francisco Bay Area, which has seen steadily increasing transit ridership and decreasing solo driving to work as a percentage, according to the report.

What are the stakes if California can’t start solving this problem in the next decade? A U.N. report on climate change recently concluded that limiting global warming to 1.5 C would “require more policies that get people out of their cars — into ride-sharing and public transportation, if not bikes and scooters — even as cars switch from fossil fuels to electrics.” In order to keep the world on track to stay within 1.5 Celsius, the report stated that emission reductions would have to “come predominantly from the transport and industry sectors” and that countries couldn’t just rely on zero-emission vehicles alone.

Yet as the report shows, California’s current land use policies are not helping with this goal. We need to discourage development in car-dependent areas while promoting growth close to jobs, as SB 50 would allow. And at the same time, we need to invest in better transit service. Otherwise, California and jurisdictions like it around the world will fail to avert the coming climate catastrophe.

Climate change exacerbates the droughts, floods, and wildfires that Californians now regularly experience, making them even more extreme and unpredictable. Gavin Newsom, California’s next governor, faces the urgent challenge of simultaneously preparing for inevitable disaster, improving the quality of life for residents, and minimizing the greenhouse gas emissions of a society of nearly 40 million people.

Climate change exacerbates the droughts, floods, and wildfires that Californians now regularly experience, making them even more extreme and unpredictable. Gavin Newsom, California’s next governor, faces the urgent challenge of simultaneously preparing for inevitable disaster, improving the quality of life for residents, and minimizing the greenhouse gas emissions of a society of nearly 40 million people.

In that spirit, UC Berkeley School of Law’s Center for Law, Energy & the Environment (CLEE) and Resources Legacy Fund (RLF) have given Governor-Elect Gavin Newsom three detailed sets of actions he can take immediately to address wildfire and forest management; drought, flood, and drinking water safety and affordability; and the stubbornly high carbon pollution of our transportation systems.

Specific recommendations include:

- Creating comprehensive, data-driven maps that identify the highest-risk wildfire areas to help the state target investments in emergency response programs and vegetation treatment;

- Accelerating the consolidation of small water systems in disadvantaged communities that consistently do not receive adequate supplies of safe drinking water; and

- Giving local governments incentives to change commercial zoning to increase transit-accessible, affordable housing and reduce the number of miles people drive.

The report also recommends creating incentives for local governments to limit development in high-risk fire areas, designing a system that dedicates a volume of water for the environment to be managed for ecosystem recovery, and setting stringent housing, transportation and greenhouse gas reduction criteria for cities looking to expand or change their boundaries.

Each set of recommendations arose from separate, half-day symposia involving a dozen or more practitioners and experts with perspectives on wildfire, water, and the nexus of climate change, housing, and transportation. Experts included local government officials, former state agency heads, environmental advocates, industry leaders, and academic researchers.

RLF and CLEE organized the panels, moderated by me and Sacramento Mayor and former Senate President pro Tempore Darrell Steinberg. Despite often divergent perspectives, panelists worked to find agreement on near-term actions. After the discussions, CLEE and RLF distilled the top recommended actions with participant input.

RLF and CLEE delivered the recommendations to Governor-Elect Newsom, Chief of Staff Ann O’Leary, and Cabinet Secretary Ana Matosantos last week.

A few themes emerged in the discussions and recommended actions:

- Cities and counties hold primary authority for deciding whether people live in harm’s reach of wildfire, drought, or flood and whether they can get to jobs and services without long vehicle commutes. Wherever possible, the state should use incentives to spur local government actions that align with statewide goals such as reducing vehicle emissions or hardening communities against fire risk. But some situations – such as the provision of clean drinking water – warrant state regulation.

- The new governor should align the way state agencies spend money in order to achieve his priorities. Federal and state transportation dollars, for example, should be directed to projects that help reduce the number of miles people drive.

- Strong leadership and systematic coordination from the governor’s office are crucial to driving progress across departments toward a common goal. The new governor should appoint leaders in each area who can spearhead cohesive, rapid action across agencies and throughout state government.

The specific recommendations and panel members can be found here. Hopefully these recommendations will help the new governor and the public be better prepared for the environmental threats we face in California.

Last year, State Senator Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco) went right to the heart of California’s massive housing shortage in its job-rich centers with SB 827, which would have limited local restrictions on housing near transit. The bill went down in committee, a victim of election year politics and diverse opposition from wealthy homeowners, tenants rights advocates, and even a few misguided environmental organizations.

Last year, State Senator Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco) went right to the heart of California’s massive housing shortage in its job-rich centers with SB 827, which would have limited local restrictions on housing near transit. The bill went down in committee, a victim of election year politics and diverse opposition from wealthy homeowners, tenants rights advocates, and even a few misguided environmental organizations.

Now Senator Wiener is back at it with Senate Bill 50, which retains most of the heart of SB 827 but with a few changes to address the anti-displacement concerns over low-income tenants who might be evicted with new infill development.

Here is a summary of the provisions:

- Easing local zoning restrictions on new housing: SB 50 would eliminate local restrictions on density and on-site parking requirements greater than 0.5 spaces per unit for residential projects within one-half mile of “major transit” (rail and ferry) stops, as well as projects within one-quarter mile of major bus stops. It would also reduce the minimum floor-area ratio (percentage of the parcel that is developed) and height restrictions to nothing less than 45 feet within one-half mile and 55 feet within one-quarter mile of rail and ferry stops. Notably, these height limits are lower than the original version of SB 827 but basically consistent with the amended version before it was killed in committee.

- Geographic applicability: SB 50 is both more and less restrictive in its applicable geography than SB 827. The one-half mile radius is consistent, but now it no longer applies to all half-mile areas around major bus stops. Instead, the bill only applies its basic provisions to one-quarter mile of high-quality bus stops (defined as having peak commute headways of 15 minutes or less). It’s more expansive though in that it now applies to communities that are determined to be “job rich” and affluent, but not necessarily close to transit. The Governor’s Office of Planning and Research and Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) are charged with making the determination of what constitutes such a community, based on loose factors like proximity to jobs, high area median income relative to the relevant region, and high-quality public schools. And notably, the bill now applies to housing not just on residentially zoned land but land that may also be zoned commercial or mixed-use but allows for housing, too. But off the table (more below) are “sensitive communities” at risk of gentrification and displacement.

- Tenant protections & affordability requirements: the final amended version of SB 827 contained some strong anti-displacement provisions, and this bill picks up on those changes and expands them. For example, the bill does not apply to any properties that have tenants or have had a tenant within the last seven years. It also delays implementation in “sensitive communities” at risk of displacement until 2025, giving these areas from 2020 to 2025 to develop community-led plans to address growth and displacement. These communities would be determined by HCD based on factors like percentage of tenants below the poverty line, although it’s otherwise unclear how HCD would determine them. Finally, the bill includes minimum affordable housing requirement for projects requesting these local waivers (although that percentage is not yet determined yet in the bill).

With these changes, Sen. Wiener has already expanded the initial coalition in support — or at least not opposed at this point. For example, the powerful State Building & Construction Trades Council of California is supportive, as the bill explicitly allows existing local wage standards to remain unaffected. And tenants’ rights groups like Strategic Actions for a Just Economy in Los Angeles have not opposed the bill yet and have been in ongoing discussions with Sen. Wiener’s office. It otherwise seems inevitable though that the League of California Cities will oppose. So the question will be: will the coalition in support be powerful enough to override wealthy communities and their elected representatives, who will inevitably oppose?

In terms of the bill’s effectiveness, like SB 827 it would be a monumental shift in California housing policy that would address one of the core impediments to new housing construction: restrictive local zoning in job-rich areas.

Yet two provisions could undermine its effectiveness greatly, depending on how they are shaped during negotiations. First, the requirement to include a percentage of affordable homes in the buildings could render the provisions meaningless if that percentage is too high. For example, San Francisco’s voter-mandated inclusionary percentage of 25% affordable units for new development projects has contributed to a significant recent decrease in building permit applications (although other factors are at play as well), as SPUR recently documented.

In addition, placing off limits “sensitive communities” could also greatly limit its applicability without stricter and clearer criteria on how HCD will determine these communities and a sense of how many communities would be taken off the table. Otherwise the concept at first glance appears sound, as a way both to minimize opposition and reduce displacement risks in high-priority areas.

But overall, the bill retains the promise of SB 827 with a more inclusive process to bring on board more supporters. If SB 50 passes in something like its current form, it holds the potential to address the state’s housing shortage (and the emissions that result from long commutes from job-rich but housing-poor areas) in a fundamental way.

Two new infill-focused reports are out, with analysis and recommendations to improve deployment of transit-oriented buildings in both Los Angeles and Sonoma County, in the wake of the devastating wildfires there last year.

Two new infill-focused reports are out, with analysis and recommendations to improve deployment of transit-oriented buildings in both Los Angeles and Sonoma County, in the wake of the devastating wildfires there last year.

First, UCLA Lewis Center and LAPlus offer a report on how to encourage more transit-oriented development along rail transit lines in Los Angeles, while minimizing displacement of low-income renters. The report conducts seven case studies in rail neighborhoods around Los Angeles and assesses how various land use policy changes affect development going forward in these locations.

Second, the Council of Infill Builders offers recommendations on how Santa Rosa and Sonoma County can rebuild in a sustainable, downtown-oriented manner, in the wake of the wildfires there that destroyed 5% of the housing stock in Santa Rosa alone. The report discusses the need for greater local support from businesses and cities to promote downtown-oriented living.

While both reports have tailored recommendations for their target geographies, they make similar points. Among them: more zoning for mixed use and denser housing in rail-adjacent areas, with reduced on-site parking requirements.

As the midterm election nears next Tuesday, California’s restrictive housing policies in its urban job centers could play a central role. As residents in these major job-producing cities on the coast close their communities to new housing construction, they have forced Democratic-leaning middle- and low-income residents into “super commutes” in far-flung, inland areas. Middle class Californians are also fleeing the state altogether to lower-cost states, like Nevada or Texas.

As the midterm election nears next Tuesday, California’s restrictive housing policies in its urban job centers could play a central role. As residents in these major job-producing cities on the coast close their communities to new housing construction, they have forced Democratic-leaning middle- and low-income residents into “super commutes” in far-flung, inland areas. Middle class Californians are also fleeing the state altogether to lower-cost states, like Nevada or Texas.

And now we see that these lower-cost regions are becoming battlegrounds for control of the United States House of Representatives and possibly the United States Senate, with the influx of these new Democratic-leaning voters. For example, the Modesto district of Republican U.S. Rep. Jeff Denham is now a competitive race with challenger Josh Harder. But that district is mainly competitive because it’s had an influx of Bay Area super-commuters seeking lower-cost housing in some of those new sprawl communities.

Or take competitive Senate races in Nevada (Democrat Jacky Rosen challenging Republican Dean Heller) and Texas (Democrat Beto O’Rourke challenging Republican Ted Cruz). The influx of priced-out Californians who tend to vote Democrat could be a difference maker.

Of course, it’s not economically, environmentally or morally healthy for California’s job-producing cities that this exodus is happening. But the effect is already reverberating across the country in this coming election, as exclusive coastal housing policies re-distribute Democrats across national political battlegrounds.

Legendary urban planner Peter Calthorpe has a spooky Halloween warning for Silicon Valley types eager to disrupt transportation with autonomous driving technology:

Legendary urban planner Peter Calthorpe has a spooky Halloween warning for Silicon Valley types eager to disrupt transportation with autonomous driving technology:

When it is easier to travel in a city in self-driving cars, Mr. Calthorpe said, everyone will want to do so. And when self-driving vehicles are more affordable — which could take years to happen — people who currently rely on public transit while running their errands will instead send their cars to pick up the groceries and the dry cleaning, adding significantly to what [co-researcher] Mr. Walters and other urban planners call “total vehicle miles.”

The resulting traffic congestion could greatly imperil quality of life and our climate goals. The warning is even more urgent as Waymo recently received approval in California to operate without a driver in the vehicle.

So what’s the upside — the treat for this otherwise scary scenario? Calthorpe advocates for Autonomous Rapid Transit (ART), which would basically involve driverless buses operating in dedicated rights-of-way in urban areas. It would save labor costs, thereby allowing quick deployment and cheap operation, while fostering the density we need to meet climate goals.

ART is probably the most promising response to harnessing autonomous technology for a climate-constrained, urban world. It could turn the trick of AVs into a treat for urban dwellers.

People who don’t like infill development cite electric vehicles as an excuse to continue to sprawl. People who don’t like cars like to point out the environmental limitations of electric vehicles.

People who don’t like infill development cite electric vehicles as an excuse to continue to sprawl. People who don’t like cars like to point out the environmental limitations of electric vehicles.

And so we have a simmering tension, recently manifested in Alissa Walker’s otherwise engaging Curbed piece “When Electric Isn’t Good Enough” on the need to reduce vehicle miles traveled and reliance on single-occupancy vehicles — even if they’re electrically powered.

Reducing driving and building more walkable, bikeable and transit-friendly neighborhoods are obviously imperatives. Environmentally, we need the reduced emissions and more compact buildings that use less energy and water. Health-wise we need the exercise and social interaction. And economically, we need the savings on housing, transportation and utility bills. Walker’s piece helps makes that case.

But electric vehicles are still a crucial technology. Driving will continue regardless of development patterns, and we must decarbonize it. We should think of it as a “loading order” (to borrow an energy phrase for prioritizing efficiency over new electricity generation): first we try to reduce driving miles, then we decarbonize all remaining driving. Walker’s article is helpful in emphasizing the need for action on the first priority.

But missing from the article is mention of the crucial co-benefits of vehicle electrification. The battery revolution propelled by EV purchases means cheap energy storage to balance intermittent renewables like solar and wind power on our grid, which helps to decarbonize our electricity sector. Cheap batteries also mean we can now have battery-powered transit buses, not to mention e-bikes and e-scooters — some of the emission-reducing technologies hailed in Walker’s piece.

Overall, the article is a helpful reminder that we need to build better neighborhoods and encourage efficient modes of transportation. But we shouldn’t downplay the significance of electric vehicles as a crucial clean technology. In short, EVs are a necessary — but not sufficient — climate-fighting technology.