One of the largest Black-owned real estate companies in the country is working with residents of a co-op in San Francisco’s Fillmore neighborhood to redevelop the current sub-standard homes into a $2 billion mega-project of market-rate and affordable housing, plus an innovation center to spur local jobs. Come hear the story from the developers and community leaders themselves at a free lunch ‘n ‘learn webinar at noon PT on Wednesday, April 7th, which I’ll be moderating.

The $2 billion project will transform the Fillmore District and potentially provide a community-based model for housing redevelopment around the country. Rather than being displaced, the current, predominantly African American co-op residents will be able to move into a new eight-story apartment building at no additional cost. The residents will then receive a 15% profit share in the new market-rate units, which include new buildings rising 12 and 18 stories, as the San Francisco Chronicle reported last year.

The webinar will feature:

- Victor McFarlane, chairman and CEO of MacFarlane Partners

- Mattie Scott, President of the Freedom West board of Directors

- Landon Taylor, Co-founder of Legacy First Partners and lead advisor to Freedom West Homes Corp.

The event is organized by the Council of Infill Builders and sponsored by Allen Matkins. Register here!

President Biden yesterday unveiled his “infrastructure” plan, but it’s really his best and greatest shot to address climate change. I’ll be speaking about the plan and what it means for the climate at 10:20am PT on KQED’s Forum. You can also hear my thoughts on the electric vehicle charging aspect of the plan on yesterday’s NPR Marketplace.

The proposal calls for transformational investments in rail, bridges, and road repair, along with a decarbonized electricity grid, incentives for electric vehicles, an end to fossil fuel subsidies, and home energy retrofits, among other goals. The plan even seeks to end single-family zoning.

Tune in this morning to hear more!

If you’re interested in the past, present and future of rail transit in Los Angeles, check out the video above from my talk this week with Streets For All. My moderated comments begin about 20 minutes in. We covered everything from the dismantling of the Los Angeles streetcar network to delays building current rail lines to whether anyone alive today will ever get to ride high speed rail.

And if you don’t know Streets For All, they’re a volunteer-based organization advocating for equitable redesign of streets and the transportation network to favor transit, walking and biking, as a climate change and quality-of-life necessity in Los Angeles.

Consider becoming a member if you’re interested in these issues. I thank them for hosting me for this talk!

With the presidential election over, Joe Biden faces a U.S. Senate that still hangs in the balance. But even with a Democratic runoff sweep in Georgia next month, it will be very divided. So what will be possible for a President Biden and his administration to achieve on climate change?

Agency action, foreign policy changes, and spending can all make a difference on emissions, with any COVID stimulus and budget deals with Congress, if feasible, providing potential avenues for further climate action. Here are some ideas along those lines, broken out by key sectors of the economy.

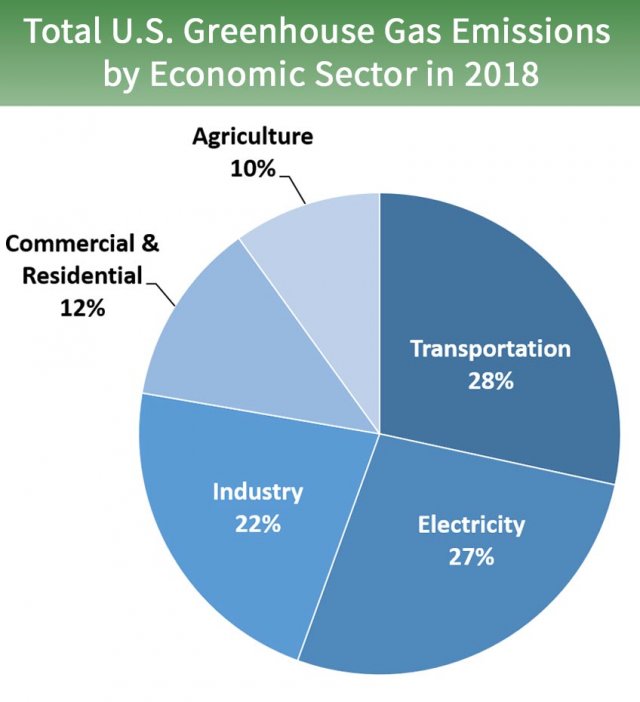

Action on Transportation

As the EPA chart above of 2018 emissions shows, transportation contributes the largest share of nationwide greenhouse gas emissions at 28%. The best way to reduce those emissions is to decrease per capita driving miles through boosting transit and the construction of housing near it, as well as switch to zero-emission vehicles, primarily battery electrics.

Transit-oriented housing is largely governed by local governments, who generally resist construction. Absent state intervention or federal legislation from a divided Congress, the Biden administration will have to make surgical regulatory changes directing more grant funds to infill housing and potentially use litigation and other enforcement tools to prevent and compensate for racially discriminatory home lending and racially exclusive local zoning and permitting practices.

On transit, a Biden administration would be very pro-rail, especially given the President-elect’s daily commuting on Amtrak in his Senate days. If the Senate flips to the Democrats, high speed rail could be a big part of any bipartisan COVID stimulus package, if it happens, which would be a lifeline to the California project that is otherwise running out of money. Other urban rail transit systems could benefit as well, and the U.S. Department of Transportation could favor and streamline grants for transit over automobile infrastructure. Notably, LA Metro CEO Phil Washington, responsible for implementing the nation’s most ambitious rail transit investment program in Los Angeles County, is chairing Biden’s transition team on transportation.

On zero-emission vehicles, Biden may have relatively strong tools to improve deployment of this critical clean technology. First, perhaps through a budget agreement with Congress, he could reinstate and extend tax credits for zero-emission vehicle purchases, which have expired for major American automakers like General Motors and Tesla. Second, he could use the enormous purchasing power of the federal government to buy zero-emission vehicle fleets. And perhaps most importantly to California, his EPA can rescind its ill-conceived attempt at a fuel economy rollback for passenger vehicles and then grant the state a waiver under the Clean Air Act to institute even more stringent state-based standards, toward Governor Newsom’s new goal of phasing out sales of new internal combustion engines by 2035.

Reducing Electricity Emissions

The electricity sectors comes in a close second place, with 27% of the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions. The move toward renewable energy, particularly solar PV and wind turbines, is so strong that even Trump had difficulty slowing it down during his single term in office, in order to favor his fossil fuel supporters. But nonetheless, the Trump administration created some strong headwinds which can now be reversed.

First and foremost, President-elect Biden can drop the tariffs on foreign solar manufacturers, which drove up prices for installation here in the United States. Second, as with the zero-emission vehicle tax credits, a budget deal with Congress could bolster the federal investment tax credit for solar, which steps down from the initial 30% toward an eventual phaseout for residential properties and 10% for commercial properties. The credit could also be extended to standalone energy storage technologies, like batteries and flywheels, if Biden budget negotiators play their hands well (easy for me to say). A Biden administration could also improve energy efficiency by dropping weak regulations on light bulbs and appliances like dishwashers at the U.S. Department of Energy and introducing more stringent ones instead.

Legislatively, any COVID stimulus deal (again, if it happens) could potentially contain money for a big renewable energy buildout, including for new transmission lines, grid upgrades, and technology deployment. In terms of regulations, if Biden is able to get any appointments through the Senate to agencies like the Federal Regulatory Energy Commission (FERC), that agency could make climate progress by simply letting states deploy more renewables and clean tech, including demand response, as well as potentially supporting state-based carbon prices (a move supported by Trump’s FERC appointee Neil Chatterjee, which promptly resulted in his demotion last week).

Slowing Fossil Fuel Production

The two big moves for the Biden administration will be to stop new leases for oil and gas production on public lands (including immediately restoring the Bear’s Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments) and bringing back the methane regulations on oil and gas producers that the Trump administration rolled back. As a bonus, his Interior Department could engage in smart planning to deploy more renewable energy on public lands, where appropriate, including offshore wind.

Other Climate Action

The list goes on for how the Biden administration can embed smart climate policy into all agencies and facets of government, with or without Congress. Of particular note, his appointees at financial agencies like the Federal Reserve and U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission could bolster and require climate risk disclosures for institutional and private investors. The U.S. Office of Management and Budget could ramp back up, based on the best science and economics, the social cost of carbon, which represents the cost in today’s dollars of the harm of emitting a ton of carbon dioxide equivalent gas into the atmosphere. This measure provides much of the economic justification for the federal government’s climate regulations. And of course, President-elect Biden can have the U.S. rejoin the 2015 Paris climate agreement immediately upon being sworn in (though the country will need to set a new national target).

Overall, Biden’s win means the U.S. will regain some climate leadership at the highest levels, with much that can be done through congressional negotiations, agency action, and spending. However, the stalemate in the US Senate likely means that any hopes for big new climate legislation will be dashed. As a result, continued aggressive action at the state and local level, as well as among the business community, will be critical to continue to help push the technologies and practices needed into widespread, cost-effective deployment to bring down the country’s greenhouse gas footprint.

One election certainly won’t solve climate change, and the costs continue to rise to address the impacts we’re already seeing from extreme weather. But given the current political climate, the actions described above could allow the U.S. to still make meaningful progress to reduce emissions over the next four years and beyond, even in an era of divided government.

Housing policy is at the center of all of our major societal problems in the United States:

- Care about racial justice? Restrictive housing and land use policies are responsible for our deeply segregated towns and cities.

- Climate change? Bad housing policies are the reason why so many people are forced into long, emission-spewing commutes, because they can’t afford to live close to their jobs.

- Economic inequality? Inflated home prices and rents increasingly force middle- and low-income residents into low-opportunity areas, while shutting them out of the wealth-generating possibilities of home ownership. Just to name a few issues affected by housing.

So why can’t we address the high cost of housing, particularly near transit and jobs? There are two culprits: high-income homeowners who support exclusionary local land use policies that restrict housing supply, which prevents others from moving into their communities and deprives them of the educational and economic opportunities that come with living in these areas. Second, the state and federal government is unwilling to provide sufficient public subsidies for affordable housing (though the scale of the need at this point is simply massive, especially given the country’s inability to build housing at a reasonable price).

Perhaps with these dynamics in mind, then-Lieutenant Governor Gavin Newsom campaigned for governor in 2018, promising 3.5 million new housing units to address the state’s severe housing shortfall. But after two legislative sessions, the Governor so far has no meaningful legislative accomplishments on increasing housing production. Like 2019, this just-concluded 2020 legislative session proved to be a bust (yes, Covid-19 interfered, but housing was one of the few remaining priorities that the legislature was committed to addressing this year).

Here are the gory details of the housing bills from the original legislative “housing package” in January that did not survive:

Assembly defeats:

- AB 1279 (Bloom): would have identified high-resource areas with strong indicators of exclusionary patterns and require zoning overrides to encourage production of small-scale market-rate housing projects and larger-scale mixed-income affordable projects.

- AB 2323 (Friedman): would have expanded CEQA infill exemptions to projects in low-vehicle miles traveled (VMT) areas.

- AB 3040 (Chiu): would have incentivized cities to upzone to allow for fourplexes in neighborhoods currently zoned solely for single-family housing.

- AB 3107 (Bloom): would have allowed streamlined rezoning of commercial land for housing.

- AB 3279 (Friedman): would have amended administrative and judicial review for various projects under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA).

Senate defeats:

- SB 899 (Wiener): would have streamlined review for religious institutions seeking to build housing on their property.

- SB 902 (Wiener): would have streamlined approval for up to 10 housing units per parcel near transit.

- SB 995 (Atkins): would have fast-tracked CEQA review for environmentally beneficial infill projects.

- SB 1085 (Skinner): would have expanded density bonus law by allowing rental housing developers to increase the size of their projects 35% if at least 20% of the units were moderately priced (rent at 30% below market rate for the area).

- SB 1120 (Atkins): would have allowed two homes on every property zoned for single-family homes in California; would have also allowed single-family properties to be split into two lots.

- SB 1385 (Caballero): would have made it easier to rezone commercial land for housing and streamline approval for projects on that land.

- SB 1410 (Caballero): would have provided rental relief through tax credits to landlords to fill unpaid rent.

It’s also worth reiterating that the senate voted down in January an amended version of Senate Bill 50 (Wiener), which would have reduced local restrictions on apartments near major transit and jobs.

And strangely, SB 995, SB 1085, and SB 1120 all passed the Assembly at the last minute, but Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon scheduled the vote too late for a concurrence vote in the Senate. As a result, the bills died.

But the news was not all bad. Some housing bills did pass, including:

- AB 725 (Wicks): requires that no more than 75 percent of a city’s regionally assigned above-moderate income housing quota can be accommodated by zoning exclusively for single-family homes, with the remainder on sites with at least 4 units.

- AB 1851 (Wicks): requires local governments to approve a faith-based organization’s request to build affordable housing on their lots and allows faith-based organizations to reduce or eliminate parking requirements.

- AB 2345 (Gonzalez): increases the density bonus and the number of incentives available for a qualifying housing project.

- SB 288 (Wiener): temporarily exempts from CEQA review infill projects like bike lanes, transit, bus-only lanes, EV charging, and local actions to reduce parking minimums, among others, until 2023 (disclosure: I helped Assemblymember Laura Friedman and Assembly Natural Resources Committee chief consultant Lawrence Lingbloom draft the parking provision, along with Mott Smith of the Council of Infill Builders).

So there we have it in 2020. A few successes, but mostly a wipeout. Perhaps recognizing the urgency after two failed sessions, Governor Newsom appeared this week to offer something of a belated endorsement of SB 50 and SB 1120, two of the more consequential bills that failed in the legislature this year:

But absent strong leadership from the Governor’s office and legislative leaders, this pattern of failure on housing production will likely continue, exacerbating all the challenges I discussed above that are affected by dysfunctional housing policy. That means we can expect worsening racial injustice and segregation, greenhouse gas emissions, and economic inequality, to name just a few, until the state can finally, meaningfully address this problem.

As the United States grapples with racism and police brutality in the wake of the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers, environmentalists need not be bystanders in the debate over solutions. Environmentalism has multiple opportunities to help address institutional racism, and few issues cross cut racism and environmentalism more than housing policy.

Environmentally, housing policy that encourages urban development is crucial to reducing emissions from automobiles through decreased commute times and car dependency, as well as limiting development pressure on open space and agricultural land. And from a racial and economic justice perspective, more inclusive housing policy is vital to undoing pervasive residential segregation in America today.

While the Civil Rights movement and the resulting laws helped make explicit racism illegal in housing, predominantly white local governments and their allies can still legally practice housing racism through restrictive local zoning and permitting processes. As Michael C. Lens and Paavo Monkkonen from UCLA’s Luskin School of Public Affairs documented in a recent study, local restrictions on housing density and complex housing approval processes are highly correlated with wealthy residents walling themselves off from those with diverse incomes and of different races. And the more hands-off a state government is on housing policy in favor of “local control,” the more segregated the state will be.

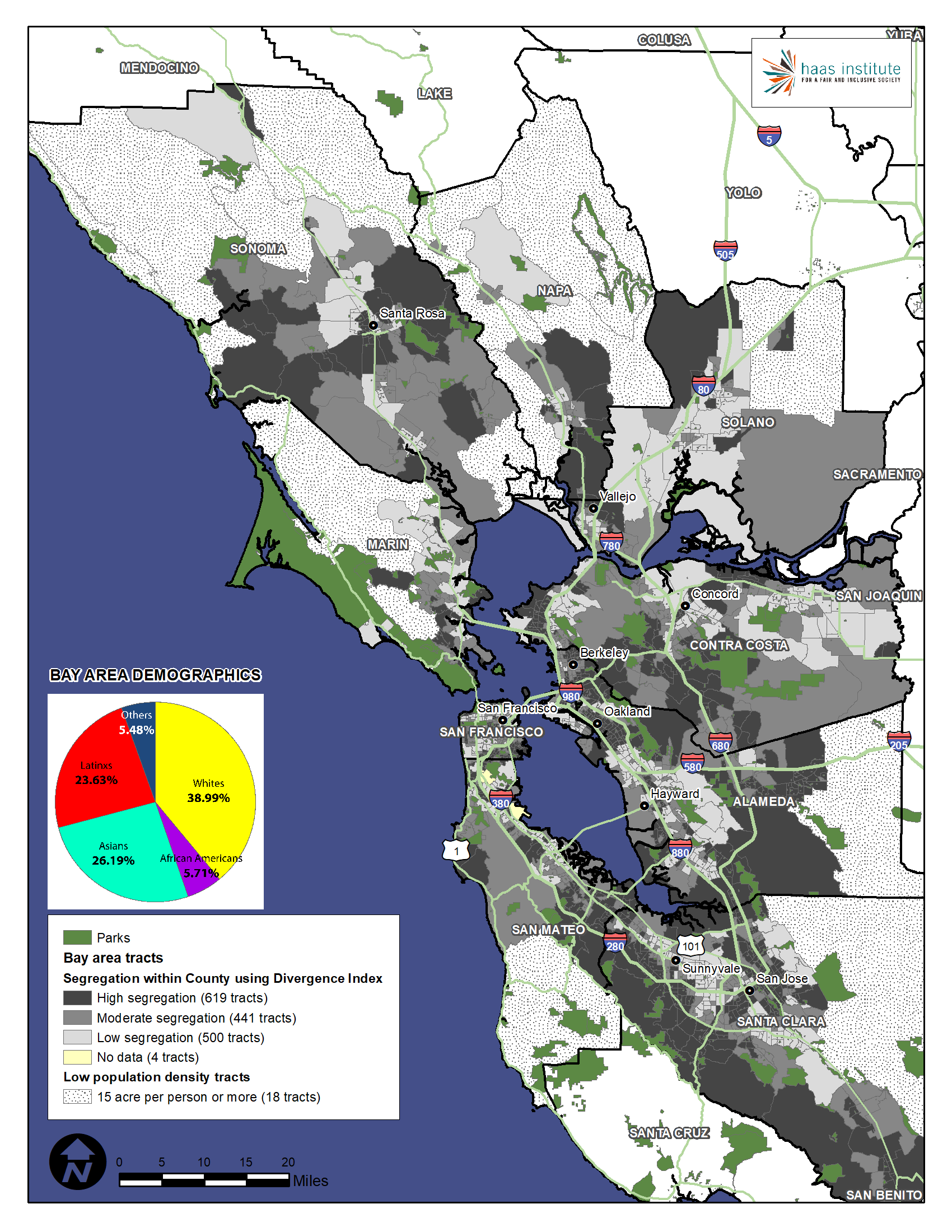

You can see this dynamic in stark terms in the San Francisco Bay Area. UC Berkeley researchers Stephen Menendian and Samir Gambhir comprehensively mapped racial demographics throughout the region, and found that whites are the most segregated racial group in the region. Although whites are just under 40 percent of the Bay Area’s population, 184 of 1582 census tracts are more than 75 percent white, with 359 tracts more than 66 percent white and 663 tracts more than 50 percent white (see map below). Contra Costa County alone in the East Bay features some of the most racially segregated white neighborhoods in the entire Bay Area: Walnut Creek (63 percent white) and Martinez (69 percent white), with Lafayette at 77 percent white (a city that was a recent New York Times poster child for exclusionary local land use policies).

The Los Angeles metro area fared no better, as the 10th most segregated metropolitan area in the country, according to one index.

So what can be done to address this fundamental form of racial segregation? Simply put, the state and federal government need to intervene to ensure that local governments cannot practice racially and economically exclusionary local zoning. By limiting the number of apartment buildings and affordable homes that are built in their communities, high-income whites are limiting racial diversity in their communities, while sending a message to people of color with incomes to afford to live in these areas that they are not welcome.

Earlier this year, the California State Senate debated a bill (SB 50 by Sen. Wiener) that would have accomplished just that: making it illegal for high-income areas to prevent apartment buildings and affordable homes near major transit. Yet a majority of state senators — many from these segregated, high-income areas, including Contra Costa, Malibu, West LA, and Silicon Valley — voted against it.

If Black Lives Matter, then surely black neighbors should too. California, like many other states around this nation, needs to address this root cause of segregation — to achieve outcomes of both environmental sustainability and racial justice.

With the COVID-19 virus shutting down cities and countries all over the world, anti-urban advocates are seizing the moment to argue that pandemics prove density is bad. For example, longtime sprawl booster Joel Kotkin argues that shelter-in-place orders and fear of contagion will push people to demand more lower-density homes, far from crowded and ailing cities.

These advocates have some support from scientists. Some public health experts point to density as a factor in spreading the disease, as the New York Times recently reported:

“Density is really an enemy in a situation like this,” said Dr. Steven Goodman, an epidemiologist at Stanford University. “With large population centers, where people are interacting with more people all the time, that’s where it’s going to spread the fastest.”

But at the same time, some of the densest nations around the world have had the most success fighting the spread of the virus, such as Taiwan, Japan, Korea, and Singapore. In particular, Taipei and Saigon city leaders (among others) have been extremely effective in controlling the contagion.

By contrast, low-density suburbs have been among the first sites where the virus took hold in the U.S., such as in Kirkland, Washington, and New Rochelle, New York. Similarly, the outbreak in Italy began in small towns outside of Milan.

Given this evidence to date, governance appears to be far more important a factor than density in limiting the spread of the virus. Furthermore, density could actually be more helpful in controlling the spread, as governments can more easily enforce sheltering in place in smaller zones, while emergency response times and trips to the hospitals are typically faster than in far-flung rural areas (which also suffer a dearth of available medical facilities, as my colleague Dan Farber pointed out).

But the question remains: could the pandemic dampen demand for housing in dense urban environments, regardless of the science? People may still (perhaps irrationally) fear a dense environment as a disease-spreader. Or they may emerge scarred from this era of “sheltering in place” and prefer larger homes with outdoor space, just in case another pandemic requires a new round of society-wide house arrest.

History may provide some guide in answering this question, as low-density homes in the 1920s were certainly sold to the public as antidotes to disease-ridden, crowded cities. As Emily Badger noted in the New York Times, “[r]espiratory diseases in the early 20th century encouraged city dwellers to prize light and air, and something that looked more like country living.”

But as policy makers weigh options to boost density, they should keep in mind the myriad public health benefits that density can provide. It can foster more physical fitness from increased walking and biking instead of sedentary, automobile-based sprawl; mental health benefits from strong and frequent community interactions; and stronger health care from pooling resources for big public hospitals.

Furthermore, in an era of climate change, living in more compact environments can guard against extreme weather events. In California, for example, urban neighborhoods are among the most fire-safe during destructive and worsening wildfires, while also largely avoiding the electricity shut-offs needed to avoid igniting fires in high-fire sprawl zones. From a public safety perspective, density can now save lives during wildfires.

And sheltering in place in a more compact environment can bring elements of joy and community during a time that can otherwise feature crushing physical and emotional isolation. Witness scenes of a balcony opera performance in Florence to help neighbors cope with the lockdown or police in Mallorca, Spain singing songs for neighbors while enforcing the quarantine.

The human connection found in dense neighborhoods can not only help us get through this particular challenging time in human history, it can build the foundations for a healthier, more sustainable future. The current pandemic won’t change that reality.

Sen. Scott Wiener is back trying to boost California housing production again, after his SB 50 legislation to upzone for apartments around transit died in the State Senate in January. This time, he’s proposing a “lighter touch” approach, salvaging an SB 50 provision that would end single-family zoning across the state.

Senate Bill 902 would authorize minimum residential zoning of duplexes in unincorporated county areas or cities under 10,000 residents. Triplexes would be the minimum density for cities between 10,000 and 50,000 residents, while fourplexes would be allowed for cities of 50,000 or more.

Furthermore, while local standards on height, setbacks, and fees, etc. would remain in place, any approval for these multiplexes would be “by right,” meaning environmental review would not apply under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) and permits would not be discretionary. In addition, the bill would not apply to parcels with renters any time in the last seven years, historic structures, or high-fire zones.

But wait, there’s more — and this time with a more explicit transit and environmental hook.

SB 902 would also allow local governments the option of rezoning any parcel (including for commercial uses) for up to 10 units in density, provided the parcel is located in a “transit-rich area, a jobs-rich area, or an urban infill site.” The definition of transit-rich means within one-half mile of any rail station or major bus stop, and urban infill site essentially means a previously developed spot surrounded by existing uses on at least 3 or 4 sides. “Jobs-rich” would need to be defined by the state’s planning and housing agencies. Like the multiplex provision, all permitting for these 10-unit parcels would be by-right and therefore not subject to CEQA.

This 10-unit opt-in provision holds the most promise to boost transit ridership and reduce vehicle miles traveled (aka “traffic”), the reason the state is now falling behind on transportation emissions. By allowing an opt-in for greater density, SB 902 provides off-the-shelf tools for local governments that actually want to see more housing near transit and jobs.

That said, the problem in California is that too many transit-rich, high-income local communities want nothing to do with more density. So many of the most critical transit-rich communities (San Francisco Bay Area suburbs and Westside Los Angeles cities like Beverly Hills) likely won’t budge on this tool. Their property-rich residents are just fine with their neighborhoods as they are.

The upside for the environment on the multiplex provision is that accommodating more residents in existing residential neighborhoods could also boost transit, if those new multiplexes are near rail stations and bus stops. And if those new residents drive, at least they would presumably have a shorter commute than if they lived in new exurban sprawl communities (the primary affordable housing alternative, short of leaving the state altogether).

The potential downside is that many of these multiplexes might be in far-flung subdivisions, meaning the new residents will have longer commutes than if SB 50 had passed and they could have lived in an apartment near transit. But the SB 50 opportunity, and all the mandatory affordable housing that would have come with it, is now passed.

As for the politics on SB 902, it seems likely it will be similar to SB 50. Wealthy suburbanites that sank SB 50 will be back en masse to oppose SB 902. Labor may not like the by-right provision (they use CEQA to force project labor agreements on developers) but may appreciate the construction jobs.

The political wildcard will be equity and affordable housing groups, which helped sink SB 50. Will they care about suburban upzoning? Some of these affected areas will have low-income tenants. While as mentioned the bill doesn’t allow redevelopment with renters present anytime in the last seven years, many tenant advocates may not care. Some are even hostile to market-rate development of any type, hoping instead for a government takeover of housing production. So it will be critical to see what positions they take on SB 902, as their opposition to SB 50 provided important political cover for wealthy opponents.

In addition, will environmental groups step up to support the measure? Most were MIA on SB 50, with the exception of NRDC, ClimateResolve and a few others. Some were even opposed, cowed by the tenant group opposition or beholden to NIMBY constituents. So SB 902 gives them a fresh opportunity to finally develop a coherent position on this most pressing environmental issue.

Ultimately, if Sen. Wiener can at least limit tenant group opposition, along with the wealthy NIMBYs who may be more scandalized by the prospect of an apartment building than a triplex, he may have a chance to get the bill passed. And ultimately, it will require the governor, who campaigned on 3.5 million new housing units but has instead seen backwards progress, to step up and get more involved in the political process.

Either way, if the bill has legs, we’ll likely see many changes as it winds its way through the process of political compromise. I’ll be following them closely.

California (and the nation as a whole) is getting worse in our efforts to reduce emissions from transportation (i.e. driving). Last week, I gave a talk in the UC Berkeley Institute of Transportation Studies lecture series on what we can do about it. You can view the recording here:

In brief, we’re failing because driving miles are up while transit usage is down, in part due to poor land use policies that pushing housing farther from jobs. We need to encourage housing near transit and encourage electric vehicle usage for all other driving.

And on the subject of how we’re failing to build enough housing near transit, you can view a recording of a January 30th symposium at UC Hastings School of Law on this topic, featuring two panel discussions (I spoke on the second) and a closing keynote from State Senator Scott Wiener. You can also read a summary of the symposium from Hastings student Leigha Beckman, who helped organize the event.

Happy viewing!

The California State Senate this morning (for a second time after an initial vote last night) narrowly and finally killed SB 50, a major climate-land use bill that would have allowed apartment buildings near major transit stops and job centers. Despite high-profile opposition from some low-income tenants groups, the senators voting against the bill largely represent affluent suburbs.

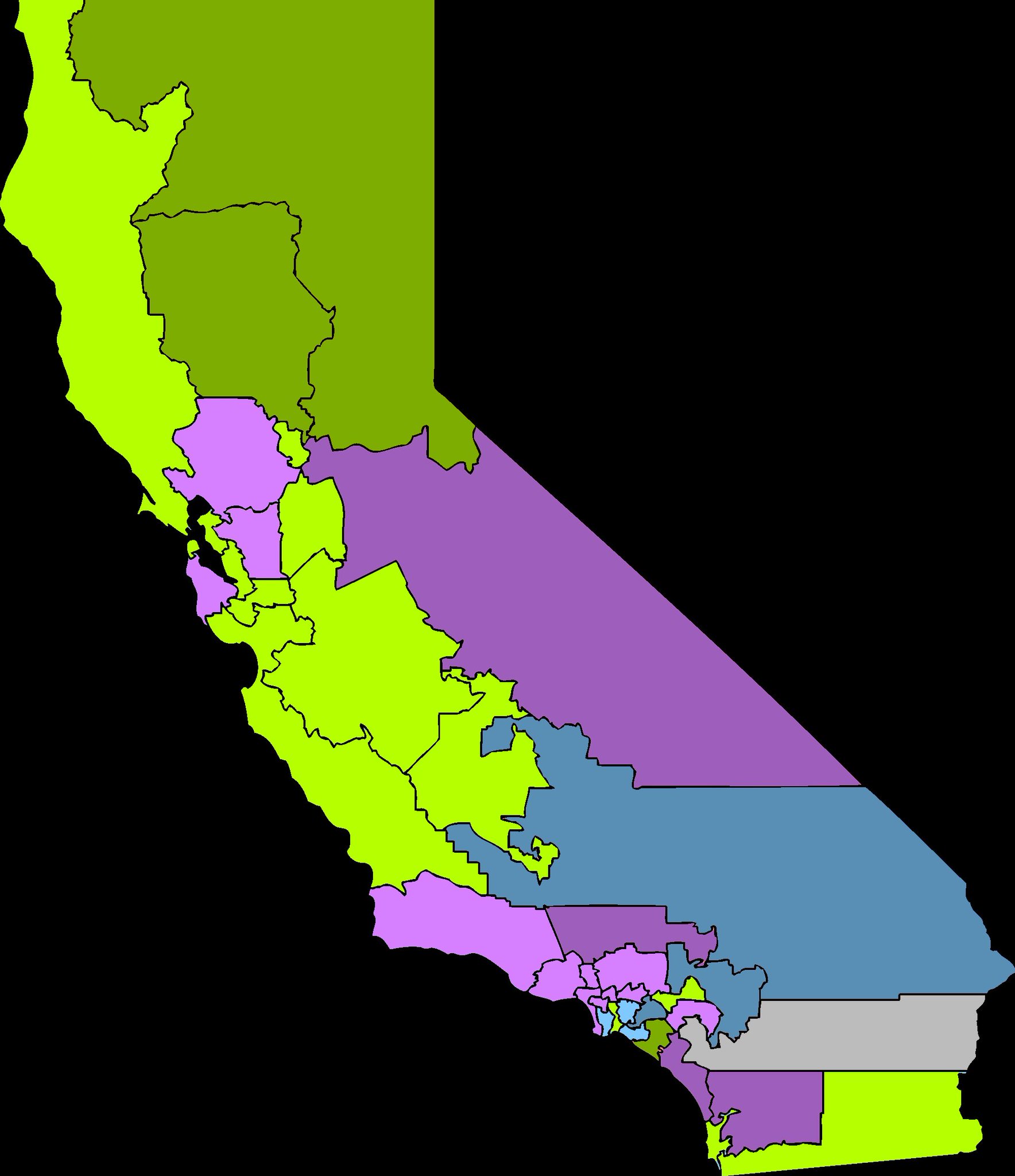

To illustrate the geographical divide, a Twitter user put together this map of the senate districts and votes, with purple opposed, green in support (light for Democrat and dark for Republican), and blue abstaining:

As you can see, the “opposed” senators largely cluster along on the affluent coastal and suburban areas. This dynamic is particularly apparent in the San Francisco Bay Area, where representatives of the urban core supported the bill (including bill author Sen. Scott Wiener and Sen. Nancy Skinner). But the senators representing the suburban, high-income Silicon Valley communities (Sen. Jerry Hill), affluent East Bay suburbs (Sen. Steve Glazer), and the Napa area (Sen. Bill Dodd) were all opposed.

Meanwhile, Southern California Democrats representing high-income coastal suburbs were almost uniformly opposed:

- Sen. Hannah-Beth Jackson, representing Santa Barbara communities;

- Sen. Henry Stern, representing Malibu and suburbs north of urban Los Angeles;

- Sen. Ben Allen, representing the Westside of Los Angeles, including Manhattan Beach and Beverly Hills;

- Sen. Anthony Portantino, representing La Cañada Flintridge and who had unilaterally shelved the bill last year in his committee; and

- Sen. Bob Hertzberg, representing the San Fernando Valley.

Notably, there were some standout “profiles in courage” votes in favor of the bill, including:

- Sen. Lena Gonzalez from Long Beach, despite opposition from city leaders in her district;

- Sen. Brian Dahle from the conservative, northern inland part of the state, who recognized the damage sprawl does to farmland;

- Sen. Bill Monning of Carmel who spoke passionately about the inequality and devastating commutes wrought by exclusive local land use policies; and

- Sen. John Moorlach of coastal Orange County, a Republican (and bill co-author) who appreciated the legislation giving more property rights to landowners.

What were the argument of opponents? They largely involved these issues:

“The bill will not produce enough affordable housing.” The bill in fact contained minimum requirements that projects receiving benefits under the bill include affordable units. As a result, SB 50-type reform would result in the biggest boost to subsidized affordable units in the state’s history, at possibly a seven-fold increase.

“SB 50 takes away local control.” To the contrary, the bill would give low-income communities five years to develop local plans for infill housing and two years for other communities to plan to meet these standards. Locals would be free to set more aggressive standards on affordability and relax restrictions even more if they wanted to do so. SB 50 also did not alter local permit approval processes. Furthermore, for senators who profess to care about the housing shortage, local control is the single biggest cause of the shortage, particularly through restrictive zoning.

“The bill will lead to gentrification and displacement.” This is a real, yet overstated, concern that the bill addressed with numerous provisions to protect against new developments displacing low-income tenants (a massive, ongoing problem that predates SB 50 and is made worse by the exclusionary housing policies SB 50 was designed to prevent). Furthermore, local governments were free to go beyond those protections. Second, as UC Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation documented, any projects under the bill only “pencil” in high-income areas where developers get higher returns. Finally, as the Urban Displacement Project at UC Berkeley (in collaboration with researchers at UCLA and Portland State) found, new market-rate and affordable housing at a regional scale reduces gentrification and displacement overall.

Finally, Sen. Henry Stern uniquely argued against the bill for encouraging development in high-fire zones. It was an odd argument, considering that the SB 50 zones around transit are in some of the only non-fire, urban zones in the state, while the bill contained explicit language preventing application in high-severity zones. Furthermore, encouraging growth in infill areas reduces pressure to sprawl into the same wildlands Sen. Stern is worried about. Yet Sen. Stern was convinced that the protections weren’t strong enough and conceivably was worried that the provision in the bill allowing conversion of single-family homes into fourplexes would put more people into harms way. Given this logic, will Sen. Stern now support a bill banning new construction in high-fire zones? Or would he have supported the bill with an amendment banning such construction? He did not respond to these questions on his Facebook page.

So what’s next? The bill or some form of it could be brought back this legislative session as a “gut-and-amend” of an existing bill. Indeed, Senate pro tem Toni Atkins vowed shortly after the vote to bring a housing production bill back before the legislature this session. Supporters could also try a more limited approach, such as exempting controversial parts of the state from the bill.

Otherwise, given the long-term problem and entrenched opposition to change, the fact that such a landmark bill only fell three votes short is quite an accomplishment. Since the problem will only get worse, the political pressure to act will increase. That means that something like SB 50 will ultimately pass in California. It will be too late for those priced out in the near term, and possibly too late to address our 2030 climate goals, which will require reduced driving miles from housing closer to jobs and transit absent major technological innovation. But it will happen, because reforming our land use governance is the only way to solve this problem.