California legislators patted themselves on the back when they passed a housing package this sessions raising money for affordable housing. But these tough votes to hike real estate document fees (SB 2) and place a bond measure on the ballot (SB 3) will barely make a dent in subsidizing the state out of its extreme housing shortage.

Real estate developer John McNellis runs through the numbers on The Registry, which are pretty shocking in their paltriness, given the scale of the problem:

According to the Los Angeles Times, San Francisco’s 700-unit Hunters View low-income housing project cost $450 million or $643,000 a unit. While appallingly high, that number sounds about right. Thus, if SB2 actually raises $250 million a year, California could add another 388 low-income units annually. And the whole $4 billion from SB 3 would be gone after 6,220 new units. In a state which needs to add 100,000 new dwellings a year just to keep up with its population growth—and not allow the housing crisis to worsen—this is truly spitting in the ocean.

But it gets worse. As McNellis points out, lack of money is only part of the problem. Neighborhood opposition to new affordable projects — which also affects market-rate projects but with more intensity given antipathy to people who need subsidized homes — makes implementation of these projects more difficult:

The problem is you can’t spend affordable-housing money. Last year, the citizens of Los Angeles generously voted to increase their property taxes by $1.2 billion to build housing for the homeless. This year, the somewhat less compassionate Angelenos in Boyle Heights blocked a proposed 49-unit homeless shelter in their neighborhood, a political scenario that has been played out countless times in nearly every city in the state. Tie-dyed progressives, kind-hearted liberals, even Orange County conservatives are all in favor of low-income housing…in someone else’s neighborhood.

Affordable housing advocates would be smart to respond to this dynamic by fighting for more than just more money to subsidize these few expensive projects. Instead, they should be working to lower construction costs overall and reduce neighborhood opposition to new projects, from market rate to affordable ones.

Otherwise, the problem will continue to worsen. And the money we do spend will become increasingly less effective and wasted.

The story is fairly well known: Los Angeles used to have one of the biggest public transportation systems in the world, with the Red and Yellow trolley cars delivering people from their “streetcar subdivision” homes to the city center and beyond. But the automobile — and not an automaker conspiracy — proved more appealing to Angelenos than sitting on a crowded, tardy, and unreliable streetcar. And thus the system fell into disrepair, disuse, and extinction.

The story is fairly well known: Los Angeles used to have one of the biggest public transportation systems in the world, with the Red and Yellow trolley cars delivering people from their “streetcar subdivision” homes to the city center and beyond. But the automobile — and not an automaker conspiracy — proved more appealing to Angelenos than sitting on a crowded, tardy, and unreliable streetcar. And thus the system fell into disrepair, disuse, and extinction.

Curbed LA delves back into this history and helps dispel the myth that car companies undid the streetcars. In the piece, reporter Elijah Chiland asked me if anything could have been done to avoid abandoning the trolley streetcars in favor of the short-lived functionality of the automobile:

Elkind says the streetcar still could have been saved, but that “it would have taken some imagination and foresight on the part of the public to think, ‘what if we did subsidize this transit service? We might be able to address some of the problems that we have and make it a better service.'”

For whatever reason, that just didn’t happen. “The leadership wasn’t there and the foresight wasn’t there,” he says.

In the matter of the streetcar’s untimely demise, we Angelenos may have no one to blame but ourselves.

Chiland asked a good question. Certainly many European cities decided not to ditch their streetcars during the post-war era, and they are now better off for it (although most American cities did abandon theirs, from Washington DC to the Bay Area).

Chiland asked a good question. Certainly many European cities decided not to ditch their streetcars during the post-war era, and they are now better off for it (although most American cities did abandon theirs, from Washington DC to the Bay Area).

But during a brief moment in the history of the rise of the automobile, Downtown Los Angeles officials experimented with ditching the automobile during peak hours. In the 1920s, they issued a short-lived ban on parking during certain daytime hours. But the public (and downtown business leaders) rebelled, and the policy was scrapped. During that time though when car parking was banned, streetcars evidently regained their prominence downtown and avoided the sometimes 60-minute delays caused by car traffic halting the trains, which had undermined rail service and contributed to its unpopularity.

So local policies on critical automobile issues like parking, as well as support for auto-oriented infrastructure, ultimately sealed the streetcars fate.

It’s too bad, because now Los Angeles is trying to rebuild much of that streetcar system at a huge cost, while also trying to retrofit existing car-oriented neighborhoods into more compact, walkable development. It’s hard to undo what’s already been done, but a growing population and demand for new housing presents the region with an opportunity to correct some of these past mistakes.

The frenzy is over. The California legislature finished its session last week and sent its approved bills onto the governor. Casual observers note the big “victories” on housing:

The frenzy is over. The California legislature finished its session last week and sent its approved bills onto the governor. Casual observers note the big “victories” on housing:

- A supermajority vote to raise fees on real estate documents to fund affordable housing;

- Another supermajority vote to approve a bond measure to go before the voters to fund even more affordable housing;

- A win for SB 35, to streamline local approvals for new housing in cities and counties that aren’t providing enough of it also passed; and

- The “sleeper” AB 1568 (Bloom), which will improves infrastructure financing for infill projects under the acronym NIFTI (Neighborhood Infill Finance and Transit Improvements Act).

But as I wrote last week, SB 35 is the one that really gets to the heart of the problem of the housing shortage in California. The new revenue measures are drops in a seemingly bottomless bucket, as local governments consistently prevent new housing from getting built, particularly in job-rich infill areas. SB 35 instead starts to deregulate housing at the local level. California will need much more of that approach to solve this crisis.

Finally, on renewable energy, the state suffered a setback. SB 100, to increase the renewable mandate to 60% by 2030 and 100% by 2045, was kicked into next year, as was the plan to regionalize California’s grid to encourage more renewables across the west and lower electricity rates for all. But the stalling of these bills gives the legislature and climate advocates a good place to start on next year’s priorities.

Next up: we’ll see what the governor signs in the coming weeks.

California legislators are in the final week of the session, and there’s a scramble on bills related to housing and renewable energy. Here’s a rundown:

California legislators are in the final week of the session, and there’s a scramble on bills related to housing and renewable energy. Here’s a rundown:

Housing

What was supposed to be the “Year of Housing” to address the state’s severe, decades-long undersupply of homes, is turning out to be pretty weak. There are basically three bills in play, out of the 150 or so to start the session:

- SB 2 (Atkins) would impose a $75-225 fee on individual California real estate transactions (which requires two-thirds vote);

- SB 3 (Beall) would authorize a $4 billion bond measure for California’s November 2018 general election ballot (which requires two-thirds vote and then approval by voters); and

- SB 35 Wiener) to force recalcitrant cities and counties to approve new infill housing projects without discretionary review.

SB 35 is the most promising, although its prevailing wage requirement will make it essentially worthless in under-performing markets in the state. All three bills are being bundled, and Democrats in the Assembly are skittish about voting for the SB 3 real estate fee in particular. If SB 2 goes down, will legislative leaders peal off SB 3 and SB 35 for separate votes, which might be successful on their own? And if they do strip SB 2 from the package, will the other two bills lose support? Stay tuned.

Meanwhile, a sleeper bill on housing is AB 1568 (Bloom), which improves infrastructure finance districts for infill projects. Using the acronym NIFTI (Neighborhood Infill Finance and Transit Improvements Act), the bill would allow these districts to capture future increases in revenue from sources like sales and occupancy taxes to pay for infrastructure improvements up front. It’s up for a floor vote shortly.

But in the end, of the big housing bundle, only SB 35 shows real promise for lasting reform by removing authority from local governments on land use. The affordable housing money is otherwise badly needed, but it’s ultimately not going to solve much of the problem. And affordable housing suffers from increased costs due to the same local land use policies that thwart market-rate housing, such as high parking requirements and limits on density. So much of these dollars will be wasted without broader land use reform.

Renewable Energy

The big bill is SB 100 (de Leon) to boost the renewable mandate in the state to 60% (from 50%) by 2030, plus a new 100% target by 2045. The goals have broad support, but the details are now creating opposition from utilities. A defeat on this bill would be a big blow, as utilities (despite their opposition) need the stronger market signal and legal permission to procure more renewables now while the federal tax credit — set to sunset soon — is still in effect.

Meanwhile, AB 726 (Holden) to restart the process of integrating California’s grid with other western states is apparently stalling. Some environmental groups and labor unions are concerned with how it would get implemented. It’s too bad, because a regional grid is going to be necessary to meet California’s long-term climate and energy goals in an affordable manner. Plus, it could help solidify political support for renewables in the states that join us, by building up a domestic clean tech industry in each of those states. If it fails this year, climate advocates should prioritize it for next year.

So on both housing and energy, there’s a lot to follow in the Golden State this week. I’ll blog again on any successful bills once the dust settles.

UPDATE: The original employee numbers from the San Francisco Chronicle that I used to make the calculations below have since been significantly revised downward. As Geekwire reports, the numbers I cited were for Amazon company-wide, not just Seattle. In fact, Amazon employees 40,000 in Washington state, not the 340,000 I cited below. While this changes the single impact of Amazon’s move, my original post was perhaps conservative in underestimating the overall demographic impact, as Amazon’s move will attract other tech companies to the region, plus spouses. So the original point of the article stands, although the impact of Amazon’s move alone will not be as significant as I originally calculated.

Amazon.com just announced that its seeking a city for its second headquarters, outside of Seattle. Could an influx of Democratic-voting tech workers to a city in a red state be enough to turn that state blue? I ran through the list of reported city contenders and their respective state vote tallies below. My goal was to find out which city, if chosen, would have the greatest effect on the state’s (and therefore the nation’s) presidential politics.

The bottom line, as you’ll see below: Democrats should be rooting for Amazon to move to Tucson, Pittsburgh, or Detroit, which would flip those states from red to blue (or in the case of Pennsylvania and Michigan, back to blue).

But first: the criteria for Amazon and the potential job numbers. According to the Chicago Tribune:

Whichever city wins Amazon’s “HQ2” will host up to 50,000 workers with salaries that could reach $100,000 annually.

The company said it’s aiming for a metropolitan area of at least 1 million residents, opening up, theoretically, a few dozen cities in the U.S., from New York to Tucson, Ariz., and a handful more in Canada. It’s unclear whether Amazon would consider a bid from a Mexican city.

But the employment — and therefore the voter — numbers could be far bigger than that. As the SF Chronicle reports:

Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos said the company plans to make the second headquarters — dubbed HQ2 — “a full equal” to its Seattle home base [which employs more than 340,000 people].

And any new Amazon home would also bring additional tech workers from other companies that would locate nearby to do business with Amazon. In short, the headquarter decision could result in a major influx of educated tech workers who could greatly affect the state’s voting results, given that tech workers vote Democrat by potentially large margins (as Nate Silver documented in 2012). The key would be for Amazon to locate in a city that could grow just enough relative to the number of Republican-leaning rural residents.

So for this exercise, I assumed that the Amazon move would eventually result in 300,000 tech workers moving in (less than Seattle’s current headquarter count and including potential workers from other tech companies). I also assumed their voting rate would be 80%-20% Democrat vs. Republican, which would roughly track the financial contributions from this sector, as a proxy for their voting habits.

That means the Amazon move could bring 240,000 new Democratic voters to the state, along with 60,000 new Republican voters. The net gain would be 180,00 new votes for the Democrats.

Could that be enough to turn a state from red to blue?

We should first note that in 2016, Trump beat Clinton by 306 to 232 electoral votes, leaving a gap of 74 electoral votes for Democrats to regain. No single state switch will reverse that gap. But a switch in one sizeable state could alter the presidential calculations going forward. Demography is destiny.

Here are the reported city candidates and the potential impact of an Amazon move on their state election results, based on the 2016 election (I left out the blue state candidate cities, because a move there would simply improve existing Democratic majorities):

FLIPPING TO BLUE

Tucson, Arizona

The state has 11 electoral college votes.

2016 presidential election results:

Trump 1.25M votes

Clinton 1.16M votes

Democrats therefore need approximately 90,000 more votes to flip the state.

Verdict: The 180,000 new votes from an Amazon move would be enough to flip the state to blue, leaving 90,000 extra Democratic votes.

Detroit, Michigan

The state has 16 electoral college votes

2016 presidential election results:

Trump 2.279M votes

Clinton 2.268M votes

Democrats therefore need approximately 11,000 more votes to flip the state

Verdict: The 180,000 new votes from an Amazon move would be more than enough to flip the state to blue, leaving a cushion of 169,000 extra Democratic votes.

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

The state has 20 electoral college votes.

2016 presidential election results:

Trump 2.970M votes

Clinton 2.926M votes

Democrats therefore need approximately 45,000 more votes to flip the state

Verdict: The 180,000 new votes from an Amazon move would be more than enough to flip the state to blue. It would leave a cushion of 135,000 extra Democratic votes.

CUTTING THE REPUBLICAN LEAD

Kansas City, Missouri

The state has 10 electoral college votes.

2016 presidential election results:

Trump 1.594M votes

Clinton 1.071M votes

Democrats therefore need approximately 520,000 more votes to flip the state.

Verdict: The 180,000 new votes from an Amazon move would not be enough to flip the state to blue. It would cut the Republican lead by about one-third though.

Nashville, Tennessee

The state has 11 electoral college votes at stake.

2016 presidential election results:

Trump 1.5M votes

Clinton 870K votes

Democrats therefore need approximately 650,000 more votes to flip the state

Verdict: The 180,000 new votes from an Amazon move would not be enough to flip the state, but it could cut the lead for Republicans by about a quarter.

Austin, Texas

The state has 38 electoral college votes.

2016 presidential election results:

Trump 4.685M votes

Clinton 3.878M votes

Democrats therefore need approximately 810,000 more votes to flip the state

Verdict: The 180,000 new votes from an Amazon move would not be enough to flip the state to blue. It would cut the lead by about one-fifth though.

Bonus Analysis: Boise, Idaho

Note: this city does not fit Amazon’s reported criteria for a move, but the city has the makings of a future tech hub, given the low-cost of living and proximity to a lot of outdoor recreation.

Idaho otherwise has 4 electoral college votes.

2016 presidential election results:

Trump 409K votes

Clinton 190K votes

Democrats therefore need approximately 220,000 more votes to flip the state.

Verdict: The 180,000 new votes from an Amazon move would not be enough, by just 40,000 extra votes, to flip the state to blue. But it would make a significant difference in Idaho politics.

Bottom line: if Amazon moved to Tucson, Pittsburgh, or Detroit, it could potentially flip those states to blue in 2020. A Boise move would come close to flipping the state, falling short by 40,000 votes. And a move to Kansas City, Nashville or Austin would chip away at Republican voter leads in those states by the following: one-third in Missouri, one-quarter in Tennessee, and one-fifth in Texas.

So for those who care about politics, Amazon’s move could have a significant effect on the 2020 election (not to mention House and Senate races, which would need to be covered in a different post).

Now that’s the kind of prime delivery that would make Democrats happy.

Infill development offers many advantages for people: more housing, jobs and retail options closer to transit, so people don’t have to drive long distances; affordable rents and home prices as more housing is built to match demand; and climate and air quality benefits as less driving and paved open space means less pollution.

Infill development offers many advantages for people: more housing, jobs and retail options closer to transit, so people don’t have to drive long distances; affordable rents and home prices as more housing is built to match demand; and climate and air quality benefits as less driving and paved open space means less pollution.

But Hurricane Harvey and the destruction in Houston is now crystallizing another critical benefit of infill: resilience in the face of extreme weather events. As observers have noted, the devastating floods were exacerbated by land use policies that prioritized sprawl over flood control and “green infrastructure” that could have soaked up excess rainwater. More infill development would have saved this open space and avoided building homes that are now essentially destroyed and unlikely to be rebuilt.

Unfortunately, infill development is too often stymied by political barriers — not economic or environmental ones. As Paul Krugman described in an op-ed over the weekend:

In practice, however, policy all too often ends up being captured by interest groups. In sprawling cities, real-estate developers exert outsized influence, and the more these cities sprawl, the more powerful the developers get. In NIMBY cities, soaring prices make affluent homeowners even less willing to let newcomers in.

Krugman compared Houston to San Francisco as two sides of these extremes. Both cities will need infill as a climate resilience strategy: Houston for the flooding we just saw, and San Francisco in the face of sea level rise and more severe droughts (residents in infill developments use less water per capita), among other looming environmental challenges.

So perhaps one bright spot from this tragedy is that infill advocates can now point to Houston as a clear symbol of why infill is also an important adaptation strategy in a world with a rapidly changing climate.

California is on the verge of passing three big bills to address the severe housing shortage, as Rick Frank writes on Legal Planet. Two of the bills will help fund affordable housing and one will streamline local review of projects in cities and counties that haven’t met their regional housing goals, as set by the state and regional agencies.

California is on the verge of passing three big bills to address the severe housing shortage, as Rick Frank writes on Legal Planet. Two of the bills will help fund affordable housing and one will streamline local review of projects in cities and counties that haven’t met their regional housing goals, as set by the state and regional agencies.

While the affordable housing bills will help, even the billions they would set aside would be essentially a drop in the bucket compared to the need. The state is not in a position to subsidize its way out of a multi-decade long process of under-building homes.

That’s why the most effective solution is also the cheapest: take the shackles off homebuilders and let them build. That is the approach of the streamlining bill, Sen. Scott Weiner’s SB 35. Those shackles primarily involve local government policies that restrict development. They also involve myriad fees placed on developers to fund infrastructure improvements that used to be paid for by local governments, in the pre-Prop 13 days. And in other instances, they involve duplicitous, counter-productive “environmental review” mandated by a CEQA process that hasn’t caught up with current environmental needs.

But these shackles also involve high construction costs. Some of these costs are unavoidable impacts of the market and land scarcity. But many in the development community cite California wage standards as a major hurdle for building new units. And it’s greatly affected the debate around SB 35 to streamline project review, which includes a controversial prevailing wage provision (unions are still opposed to the bill though because without the local review, they lose a bargaining point to extract more worker benefits).

Liam Dillon in the Los Angeles Times has a helpful rundown of the impact of these “prevailing wage” standards that construction unions have helped put in place. Here’s a chart showing what this means in practice in a market like Los Angeles:

The article notes how challenging it is to estimate how much prevailing wage requirements add to construction costs, but it cites the following studies:

| Author | Percent Cost Increase |

|---|---|

| UC Berkeley | 9% to 37% |

| The California Institute for County Government | 11% |

| National Center for Sustainable Transportation | 15% |

| San Diego Housing Commission | 9% |

| Smart Cities Prevail | 0%* |

| Beacon Economics | 46% |

The bottom line is that prevailing wage adds costs, although we don’t know quite how much. But we do know it will slow housing production to some extent.

Of course, these requirements also bring significant benefits in paying good wages and helping to overcome the severe income inequality in the state. We want construction workers who are paid fairly for their work. But we also need more housing to lower costs for everyone else in the state. Hence the controversy.

More research on the impact of these wages would be helpful, as would discussions about alternative policies that could achieve the same ends without limiting housing production. For example, prevailing wage in hot markets like Los Angeles and the Bay Area probably won’t impact construction much. But in some of our more challenging markets that are most in need of infill development, like the Central Valley, and which are also most at-risk for sprawl, any additional requirements can sink a project before it starts.

In some ways, the prevailing wage debates fit into a larger discussion about how we ensure better living standards and wages for all in this country. Do we do it through mandates on the private sector? Or through taxes that we redistribute through social programs, to supplement private wages and benefits without directly burdening companies?

Ultimately, the state will need more creativity about how to address both challenges: wage growth and housing production, as well as more information about the scale of the impact and the potential alternative solutions available. But for now, the controversies are slowing the progress of major housing bills and potentially limiting their scope.

Joel Kotkin and Wendell Cox recently tried to explain falling transit ridership in the Orange County Register, offering an inaccurate diagnosis of the cause, along with counter-productive, infeasible solutions.

First, the problem of falling transit ridership they describe is definitely real and pressing:

[S]ince 1990, transit’s work trip market share has dropped from 5.6 percent to 5.1 percent. MTA system ridership stands at least 15 percent below 1985 levels, when there was only bus service, and the population of Los Angeles County was about 20 percent lower. In some places, like Orange County, the fall has been even more precipitous, down 30 percent since 2008.

Yet they attribute falling ridership solely to the sprawling “urban form” of Southern California, which they argue is too spread out to support much transit, particularly rail. But this factor doesn’t necessarily explain why transit ridership is down nationwide. While researchers are still examining it, it is likely due to a combination of larger trends such as low gas prices, more congestion from increasing vehicle miles traveled (which slows down buses), higher fares and decreasing service, and the rise of venture capital-subsidized Uber and Lyft.

Still, Cox and Kotkin are right that Los Angeles is generally a “spread out” city, with the downtown area employing just two percent of the region’s workers (although it has pockets of density to rival any eastern city, such as the Wilshire Corridor). As a result, transit — particularly rail — has a tougher time attracting sufficient riders in low-density areas. This decentralized pattern has also been the cause of the region’s severe traffic (and air quality) problems.

But then Kotkin and Cox — pardon the expression — go off the rails. In their view, Los Angeles’ sprawling urban form is the result of collective individual preferences, as expressed in a free market for housing — and not public policy interventions. They see the single-family home with a two-car garage and a driving commute as the dream that virtually every American wants to achieve.

According to this logic, any effort that makes it harder to live in suburban-type housing must be a form of social engineering by heavy-handed government officials or greedy developers, trampling the will of the home buyer. They use expressions to characterize this dynamic like “a growing fixation among planners and developers” and “the urbanist fantasies of planners, politicians and developers.”

And yet the evidence does not support their vision of the ideal housing situation. Land use is in fact one of the most regulated sectors of the economy, not the perfect expression of free market demand. The lack of density in economically thriving parts of Los Angeles has little to do with people’s aversion to “stack-and-pack” housing, as Kotkin and Cox term it. It is instead largely the result of highly restrictive zoning practices that prevent new multifamily housing near transit and jobs from getting built.

And yet the evidence does not support their vision of the ideal housing situation. Land use is in fact one of the most regulated sectors of the economy, not the perfect expression of free market demand. The lack of density in economically thriving parts of Los Angeles has little to do with people’s aversion to “stack-and-pack” housing, as Kotkin and Cox term it. It is instead largely the result of highly restrictive zoning practices that prevent new multifamily housing near transit and jobs from getting built.

Similarly, the suburban homes in communities far from job centers, like in the Inland Empire, are made feasible by public policies that subsidize the automobile and its related infrastructure. Basically, most home buyers have little choice: if you’re raising a young family, you’re likely priced out of expensive, job-rich neighborhoods due to the lack of new housing supply there. And you’re unlikely to want to live in high-crime urban areas with underperforming schools. As a result, your only option is cheap land in a far-flung suburban area.

Now to be sure, a sizeable percentage of home-buyers do want to live in suburban-style homes, but there are limits to that demand. In survey after survey, consumers report their strong preference for walkable neighborhoods and housing in proximity to jobs and schools. For example, a 2015 survey showed that 68% of Bay Area residents place a high or top priority on walkability for a home, while 50% want convenient access to transit from their home.

Furthermore, demographics run against the trend of suburbanization that Kotkin and Cox favor. Between 1970 and 2012, the share of households with married couples with children under 18 decreased by half, from 40 percent to 20 percent. Over that same period, the average number of people per household also declined from 3.1 to 2.6. To put it simply, these are not trends that argue for building more single-family, far-flung homes.

In short, Kotkin and Cox miss the policy support for decentralization and sprawl that contributes to the transit ridership problem. To reverse these negative ridership trends, policy makers should instead be lifting the barriers to new housing and commercial development near transit. They should also provide equitable funding for non-automobile infrastructure, such as bike lanes, pedestrian walkways, and transit. And they should price the externalities created by long-distance car commutes, such as through gas taxes that pay for the pollution and congestion pricing on crowded freeways and arterials.

But Kotkin and Cox instead advocate for unworkable solutions to address the ridership and mobility challenges. Specifically, they want more people to work from home, more Ubers and Lyfts, and a Hail Mary from autonomous vehicles to shuttle everyone around in robot cars.

First, working from home is not a viable long-term solution for many workers, given that only a certain percentage of jobs allow for this kind of arrangement, specifically office workers. Second, relying on Ubers and Lyfts, as well as autonomous vehicles, will only increase overall vehicle miles traveled in the region. This means more traffic overall, more lost open space, and more air pollution — all counter-productive results. And even if autonomous vehicles temporarily speed up freeway traffic, history has shown us time and again that increased road capacity only induces more car travel to fill it.

While Kotkin and Cox decry the worsening congestion from more “densification,” more compact neighborhoods actually decrease overall driving miles, even if congestion might worsen in the immediate areas. Along with sensible local parking policies, congestion pricing, and enhanced investments in transit, biking, and pedestrian infrastructure, the real solution is to create viable, compact neighborhoods close to jobs and transit, without forcing residents to be car dependent.

More of these transit-friendly communities would meet market demand and provide an alternatives for the growing demographic that is sick of business-as-usual housing options. It would also boost ridership on our buses and trains. But more of the status quo, as Kotkin and Cox propose, simply doubles down on failed policies that created the region’s mobility, economic, and quality-of-life problems in the first place.

Los Angeles County is a big place, with lots of urban centers to connect with rapid rail transit. Funding is limited for these expensive trains, despite the passage of two recent sales tax increases and two others passed in 1980 and 1990 respectively.

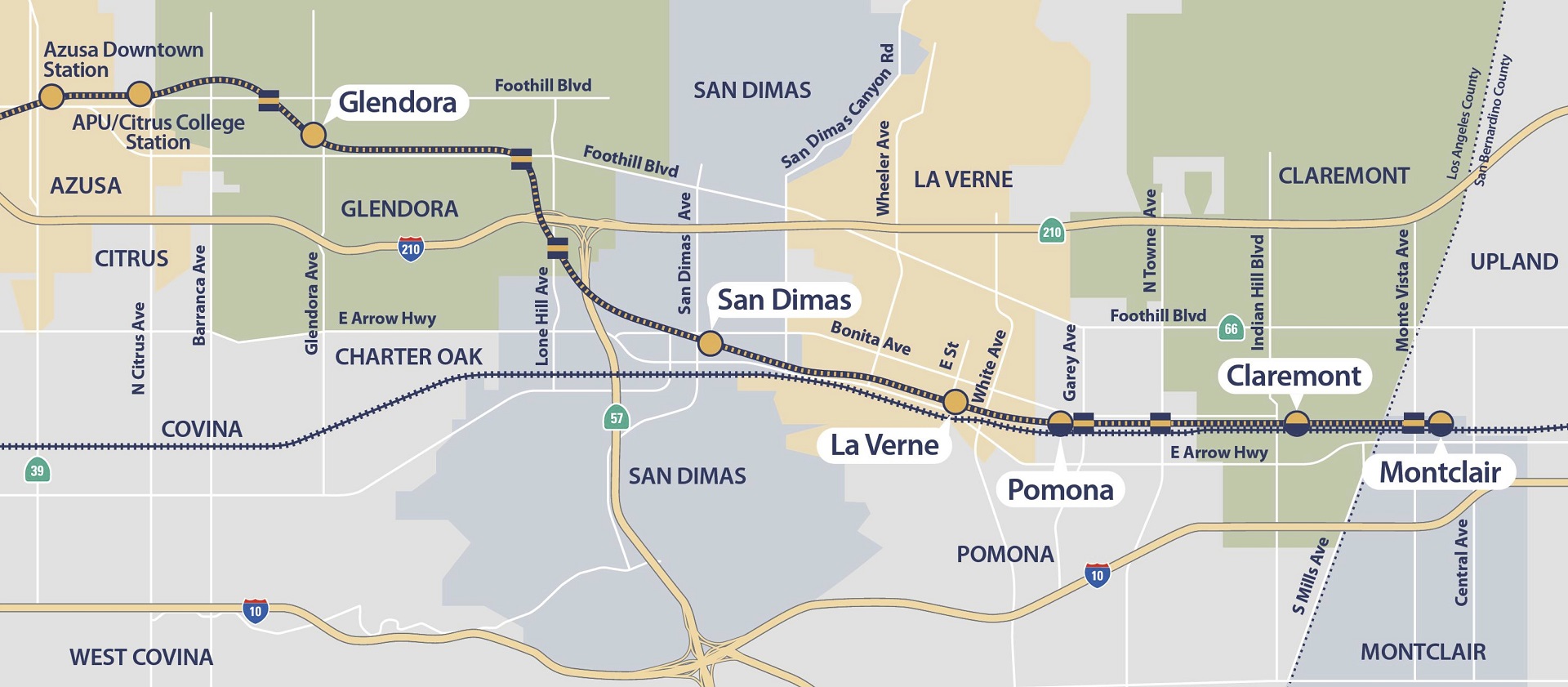

So why is the region spending these limited dollars on two rail lines in the mostly suburban, auto-oriented, low-density San Gabriel Valley? The issue is now front-and-center with the June approval of a $1.4 billion extension of the Foothill Gold Line light rail to Montclair.

The problem is that the line dovetails with an existing Metrolink line, which is a diesel train for commuters into downtown Los Angeles. This map tells the story:

The existing Gold Line extension to Azusa already is cannibalizing nearby Metrolink service, as Urbanize LA reported:

In a report prepared for the Planning and Programming Committee, Metro staff notes that there has been a precipitous drop in ridership at a nearby station on the San Bernardino Metrolink line. In the year since the completion of the extension, which Metro calls the Gold Line Extension Phase 2A, boardings at Covina station have fallen 25 percent, despite being several miles from the Gold Line terminus at Azusa Pacific University.

Even more worrying for the future of Metrolink’s highest ridership line is the Gold Line Extension Phase 2B, which will extend the light rail line from Glendora to Claremont, and with a potential contribution from the County of San Bernardino, across the County line into Montclair. Three of the new stations, in the cities of Pomona, Claremont and Montclair, will be built in the Metrolink right-of-way and have stations directly adjacent to their commuter rail counterparts, offering perhaps an alluring alternative to the existing service. While Gold Line trains will take about 15 minutes longer to travel from Montclair to Union Station, they will be far cheaper and offer service every 7-12 minutes for most of the day.

I discussed this issue with KPCC radio recently, explaining that the reason for this extra rail service is simply politics. To secure two-thirds voter approval on the recent sales tax measures for transit, local leaders had to essentially buy off San Gabriel Valley leaders with a gold-plated rail line promise, even though the region doesn’t have the ridership to justify the expense.

That’s not to say that duplicative rail service is a bad thing by definition. If the population and job density is sufficient, two rail lines in proximity can make sense. But in this case, the density isn’t there. Metro leaders should have stood up to the San Gabriel Valley and funded a right-sized transit line. That would have most likely meant bus rapid transit and not light rail, which still would have been a big transit win for the region.

It may be too late to downsize the train route, but perhaps in the meantime Metro can develop adequate policies to ensure that San Gabriel Valley and Inland Empire leaders encourage maximum densities along the route. More dense development will not only give local residents more housing and commercial service options, it will provide more riders to minimize the losses on this unfortunate decision.