It’s taken a long time, but California finally is ready to make a significant change to speed environmental review for new transit and infill projects. The Governor’s Office of Planning & Research (OPR) announced on Monday that a compromise has been reached to implement SB 743 (Steinberg, 2013), a law that made major amendments to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), the state’s law governing environmental review of new projects.

Back in 2013, the legislature passed SB 743 to change how infill projects undergo environmental review. Under the traditional regime, project proponents had to measure transportation impacts by how much the project slowed car traffic in the immediate area. The perverse result was mitigation measures to privilege automobile traffic, like street widening or stoplights for rail transit in urban environments or new roadways over bike lanes in sprawl areas.

But the true transportation impacts are on overall regional driving miles. An urban infill project may create more traffic locally but can greatly reduce regional traffic overall by locating people within walking or biking distance of jobs and services. Meanwhile, a sprawl project may have no immediate traffic impacts, but it typically dumps a huge amount of cars on regional highways, leading to more traffic and air pollution. As a result, the switch from the “level of service” (auto delay) metric to “vehicle miles traveled (VMT)” made the most sense. Most infill projects are exempted entirely under this metric, while sprawl projects would have to mitigate their impacts on regional traffic.

But OPR’s implementing guidelines with this change were held up by highway interests and their government allies, who don’t want the law to apply to highways. You can probably see why: highways are designed to do one thing only — induce more driving. And that would score poorly under this change to CEQA.

State leaders finally reached a compromise this month: the new guidelines could apply statewide to all projects (something only suggested by the statute), but new highway projects can still use the old “level of service” metric, at the discretion of the lead agency (see the PDF of the guidelines for more details at p. 77).

It’s an unfortunate but probably necessary concession to powerful highway interests. Even though freeways have consistently failed to live up to their promise of fast travel at all times, and instead brought more traffic, sprawl and air pollution to the state, many California leaders are still wedded to this infrastructure investment.

My hope is that the compromise won’t actually mean that much new highway expansion in the state. First, California isn’t planning to build a lot of new highways, outside of the ill-advised “high desert corridor” project in northern Los Angeles County. Second, even for new highway projects, CEQA’s required air quality review may necessitate an analysis of (and mitigation for) increased driving miles.

Either way, smart growth advocates can at least celebrate the good news that CEQA will finally be in harmony with the state’s other climate goals on infill development, transit, and other active transportation modes.

The guidelines though still need to be finalized by the state’s Natural Resources Agency, which will take additional months. I’ll stay tuned in case anything changes with the proposal during this time.

California is on track to meet its 2020 climate change goals, to reduce emissions by that year back to 1990 levels. Much of that success is due to the economic recession back in 2008 and significant progress reducing emissions from the electricity sector, due to the growth in renewables.

But the state is lagging in one key respect: transportation emissions. Bloomberg reported on the emissions data compiled by the nonpartisan research institute Next 10:

But the state is lagging in one key respect: transportation emissions. Bloomberg reported on the emissions data compiled by the nonpartisan research institute Next 10:

In 2015, the most recent year for which data are available, the state’s greenhouse gas emissions dropped at less than half the rate of the previous year, according to an August report from the San Francisco-based nonprofit Next 10. Low gas prices and a lack of affordable housing prompted more driving and contributed to a 3.1 percent increase in exhaust from cars, buses, and trucks, the report says. Census data show that more than 635,000 California workers had commutes of 90 minutes or more in 2015, a 40 percent jump from 2010.

The solutions are urgent: we need to reduce driving miles by building all of our new housing (an estimated 180,000 units needed per year) near transit, and we need to electrify our existing vehicle fleet and add in biofuels and hydrogen where appropriate. Otherwise, the state will not be as successful in meeting its much more aggressive climate goals for 2030, with a 40% reduction below 1990 levels called for that year.

First, advocate for a multi-billion transit line that will serve your home neighborhood. Then once it’s built, make sure nobody else can move to your neighborhood to take advantage of the taxpayer-funded transit line. It’s a classic bait-and-switch, and it’s happening now along the Expo Line in West L.A.

What’s at stake is an already-watered down city plan for rezoning Expo Line stations areas. The city’s “Exposition Corridor Transit Neighborhood Plan,” while rezoning some station-adjacent areas for higher density, still leaves a whopping 87% of the area, including most single-family neighborhoods, unchanged, and with too-high parking requirements to boot.

But this weak plan is still too much for Los Angeles City Councilmember Paul Koretz and his homeowner allies, including an exclusionary group of wealthy homeowners assembled under the name “Fix The City.” They oppose even these modest changes to land use in the transit-rich area. Essentially, they’ll get the financial and quality-of-life benefit of the Expo Line, while working to ensure no one else does.

As Laura Nelson details in the Los Angeles Times:

Koretz told the Planning Commission this month that the areas surrounding three Expo Line stations in his district “simply cannot support” more density without improvements to streets and other public infrastructure.

It’s a view shared by advocates from Fix the City, a group that has previously sued Los Angeles over development in Hollywood and has challenged the city’s sweeping transportation plan that calls for hundreds of bicycle- and bus-only lanes by 2035.

“It’s like when you buy a new appliance, you’d better read the fine print,” said Laura Lake, a Westwood resident and Fix the City board member. “This is not addressing the problems that it claims to be addressing.”

If Koretz and his allies have their way, their homeowner property values will go up with the transit access, but taxpayers around the region have to continue subsidizing the line even more because neighbors are not allowing more people to ride it. And to boot, they will keep regional traffic a mess by not allowing more people to live within an easy walk or bike ride of all the jobs near their neighborhood. Essentially, they force everyone else into long commutes while keeping housing prices high — an ongoing environmental and economic nightmare.

Thankfully there are others mobilizing against these homeowner interest groups, such as Abundant Housing L.A. But two things need to happen now: first, the Expo neighborhood plan needs serious strengthening, including elimination of parking requirements and an end to single-family home zoning near transit stops. Second, L.A. Metro needs to hold the hammer over these homeowners by threatening to curtail transit service to the area. I see no reason why taxpayers should continue to support service to an area that won’t do its part to boost ridership on the line.

Single-family zoning near transit is an idea that should have died long ago. It has no place in a bustling, modern, transit-rich environment like West L.A. The Expo Line bait-and-switch must end.

Scott Wiener, San Francisco’s state senator elected in 2016, has already authored some landmark legislation on housing (SB 35), and he’s co-authored other measures related to transportation and leading the state resistance to the Trump administration.

Scott Wiener, San Francisco’s state senator elected in 2016, has already authored some landmark legislation on housing (SB 35), and he’s co-authored other measures related to transportation and leading the state resistance to the Trump administration.

I’ll be interviewing him tonight on City Visions at 7pm to discuss these issues and what Sen. Wiener sees on tap legislatively and politically for the state in 2018. Tune in on KALW 91.7 FM in the San Francisco Bay Area or stream it live. We welcome your questions and comments!

California’s Central Valley is the state’s defining geographical feature. It’s the country’s breadbasket, with over 400 commodity crops, including all the almonds grown in the country. At the same time, it’s poverty-stricken, with Fresno the second poorest city in the U.S., and yet oil rich down by the deeply Republican Bakersfield.

California’s Central Valley is the state’s defining geographical feature. It’s the country’s breadbasket, with over 400 commodity crops, including all the almonds grown in the country. At the same time, it’s poverty-stricken, with Fresno the second poorest city in the U.S., and yet oil rich down by the deeply Republican Bakersfield.

It’s also one of the most environmentally vulnerable region in the state, with one of the most polluted air basins in the country. And as the Los Angeles and San Francisco Bay Area regions say no to new housing, sprawl is spreading into the Valley from these areas, as workers choose cheap housing and super commutes. Sprawl is also the norm around the Valley’s large cities along Route 99 on the eastern side. Like Los Angeles before it, the flat terrain means the region has no real geographical impediments to sprawl.

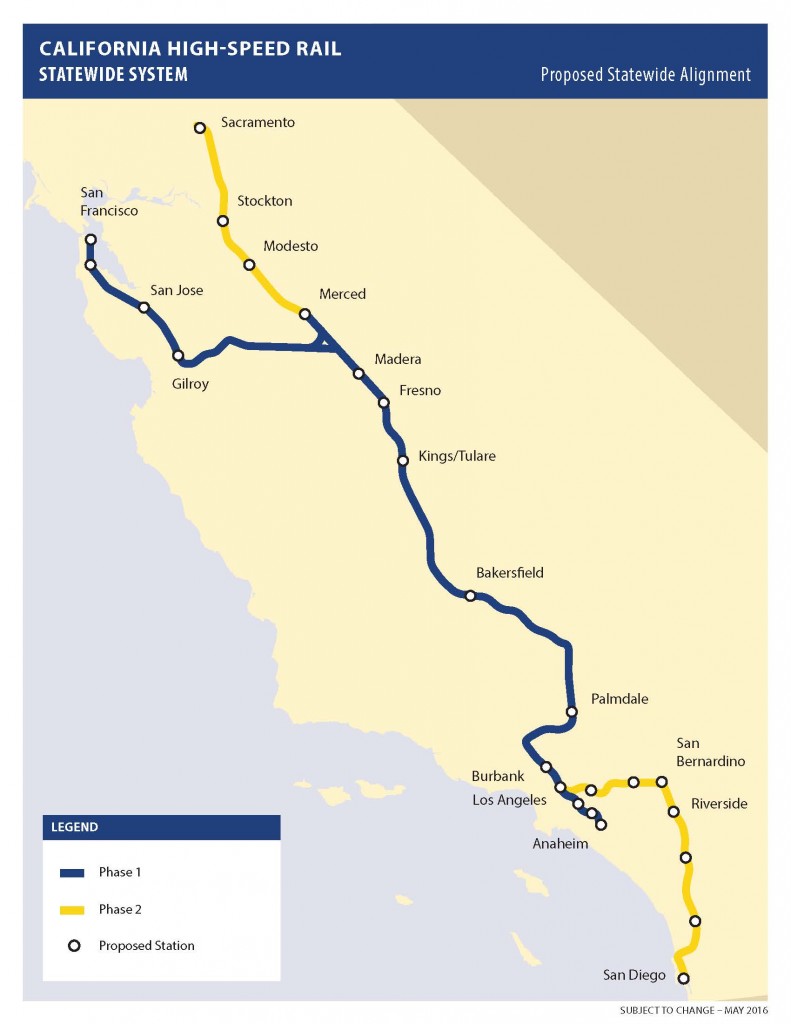

High speed rail could make the sprawl even worse, as the train will spur growth in places like Fresno, which will be just an hour or so from the booming coastal job centers (Berkeley and UCLA Law released a report on the subject in 2013, along with recommendations to combat the problem).

High speed rail could make the sprawl even worse, as the train will spur growth in places like Fresno, which will be just an hour or so from the booming coastal job centers (Berkeley and UCLA Law released a report on the subject in 2013, along with recommendations to combat the problem).

People in the Valley are well aware of the risk. Former Fresno mayor Ashley Swearengin, a rare Republican high speed rail supporter, tried to do the right thing to encourage more downtown-focused growth in Fresno and not allow the urban core to get hollowed out by competition from nearby cheap sprawl.

But Mayor Swearengin and other downtown booster’s efforts are threatened by Fresno’s neighbor Madera County next door, whose leaders prefer the model of continued sprawl over productive farmland and open space. The result will be the usual negatives we see elsewhere in the state: more traffic, worse air quality, and lost natural resources.

Marc Benjamin and BoNhia Lee detailed the new sprawl projects in the Fresno Bee last year:

Madera County is on the verge of a building boom that creates the potential for a Clovis-sized city north and west of the San Joaquin River, with construction starting this spring.

Riverstone is the largest of the approved subdivisions in the Rio Mesa Area Plan. It’s underway on 2,100 acres previously owned by Castle & Cooke on the west side of Highway 41 and north and south of Avenue 12. Castle & Cooke had plans to build there for about 25 years.

It’s the first of several subdivisions in the county’s area plan to be built. Over the past 20 years, Riverstone and other projects were targeted in lawsuits, many of which have been settled, but some still linger. But some critics contend that the new developments will worsen the region’s urban sprawl.

Principal owner Tim Jones’ vision for his nearly 6,600-home development a few miles north of Woodward Park is a subdivision with six separate themed districts. Riverstone will compete for home buyers with southeast Fresno, northwest Fresno, southeast Clovis and a new community planned south and east of Clovis North High School.

The Rio Mesa Area Plan will result in more than 30,000 homes when built out over 30 years. About 18,000 homes have county approval. The contiguous communities could incorporate to create a new Madera County city that could dwarf the city of Madera and have a population greater than Madera County’s current population of 150,000.

In the coming years, an additional 16,000 homes are proposed in Madera County. On the east side of the San Joaquin River, in Fresno County, about 6,800 homes are approved in the area around Friant and Millerton Lake.

Defenders of these sprawl projects claim that some are mixed-use developments located close to distributed job centers, minimizing the chances that they will become merely bedroom communities of Fresno. But as the development continues outward, it undercuts the market for infill housing, leading to a vicious downward spiral that we saw hit downtowns throughout the country in the middle of last century.

The best way to solve these growth issues is better regional cooperation, particularly around some type of urban growth boundaries. The growth boundaries can be de facto through mandatory farmbelts, rings of solar facilities, and possibly better pricing on sprawl projects to account for their externalities. Or they can be actual limits on growth and urban expansion outside of already-built areas.

Without concerted action, and with the high speed rail coming from Fresno to San Francisco soon, we may soon find that it’s too late to undo the damage in the Central Valley.

Halloween may be over, but the climate frights this week continue. Here are the scary highlights:

- Electric vehicle incentives in trouble: the Republican tax plan would eliminate the $7500 tax credit for EV purchases, which would likely torpedo sales for all but the luxury EVs in the short term. States might be able to dig deep to make up some of the difference, and the tax credit is set to phase out anyway for automakers over certain sales amounts, but nonetheless this would be a big blow to demand.

- Infill tax credits at risk: the Republican tax plan also targets federal programs that help revitalize infill neighborhoods. It would eliminate key programs like New Markets Tax Credits (NMTC), Historic Preservation Tax Credits (HTC), and the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program. As Smart Growth America and their infill group Locus writes in a newsletter today, “community development projects almost invariably rely on federal programs like these to fill a critical financing gap, often making the difference between a go and a no-go decision for a project penciling out.”

- Tesla Model 3 stuck in production “hell”: Tesla’s third-quarter earnings call brought bad news about the Model 3, the $35,000 mass-market EV that is struggling to meet its production targets. The company’s goal of producing 5,000 units a week by the end of 2017 has slid to the first quarter of 2018. The normally upbeat Elon Musk was apparently in a bad mood, per E&E News [paywalled]:

The call’s tone was a swing to the dark side for Musk, who on quarterly earnings calls often minimizes problems and instead trumpets the company’s successes, or announces or at least hints at some bold new initiative.

- Earth passes a carbon milestone: scientists report that the rate of carbon dioxide being released into the atmosphere accelerated at an unprecedented pace last year, reaching levels not seen in 800,000 years. Per E&E news [paywalled]:

Current levels of CO2 correspond to the Pliocene period from 3 million to 5 million years ago, when the climate was 3.5 to 5.5 degrees Fahrenheit warmer, the report found. At that time, the ice sheets of Greenland and West Antarctica were melted. Sea levels were 30-60 feet higher than they are now.

I’d say this is not a good time to invest in ocean-front property. Happy Frightful Friday!

The tide is turning against people who claim to be environmentalists but oppose urban development. Grist ran a nice profile on the burgeoning YIMBY (yes in my backyard) movement of people frustrated with high housing costs and the environmental impacts of pushing new development further out over open space.

The piece features State Senator Scott Wiener, who has taken up the legislative mantle for these YIMBY efforts and authored SB 35, one of the first state laws to start limiting local discretion over infill projects:

Environmentalists are usually thought of as folks who are trying to stop something: a destructive dam, an oil export terminal, a risky pipeline. But when it comes to housing, new-school environmentalists — like Wiener — understand that it’s necessary to support things, too. To meet California’s ambitious goals to cut pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, regulators say the state must build dense, walkable neighborhoods that allow people to ditch their cars.

The article includes a wonderfully succinct quote about why promoting infill is pro-environment, and why fighting infill is an anti-environmental act:

If you slow down development in cities, houses will sprawl out over farmland, and people will wind up making longer commutes. “You can’t legitimately call yourself an environmentalist,” Wiener says, “unless you support dense housing in walkable neighborhoods with public transportation.”

In many ways, this fight is generational and class-based, as older homeowners fight to preserve their artificially inflated and low-taxed real estate investments by choking off new supply. But as more people find themselves in the “have-nots” camp, homeowner groups will lose more battles to these YIMBYs.

So says a new study by researchers Jesper Ingvardson and Otto Nielsen from the Technical University of Denmark, as reported by The City Fix:

Ingvardson and Nielsen compare 86 metro, light rail transit (LRT) and bus rapid transit (BRT) corridors using several variables: travel time savings, increase in demand from riders, modal shift, and land use and urban development changes. In some cases, the much more economical BRTs matched and even outperformed rail.

The key for buses to match or exceed all of these major benefits of rail is to have “buses done right.” That means bus rapid transit in its own dedicated lanes, with fast boarding and frequent service.

The benefits for transit advocates and the public are huge: bus rapid transit is far cheaper than rail (often 1/5 the price) and can get built much more quickly (sometimes in 1/5 the years).

To be sure, rail is appropriate in densely populated environments and travel corridors. But most cities in the United States have many more moderate-density corridors than high-density ones. In these areas, the case for true bus rapid transit is looking more and more like a no-brainer.

This has been a tough year for the planet and our climate. With rising air and sea temperatures across the globe, we’re seeing more intense hurricanes and wildfires. But the flooding from Hurricane Harvey in Houston and the devastating fires in California’s wine country are made worse by our land use patterns.

This has been a tough year for the planet and our climate. With rising air and sea temperatures across the globe, we’re seeing more intense hurricanes and wildfires. But the flooding from Hurricane Harvey in Houston and the devastating fires in California’s wine country are made worse by our land use patterns.

As I wrote about during the Harvey floods, the Houston sprawl exacerbated the damage by paving over natural floodplains that could have absorbed some of the excess rainwater. And now in the Napa and Sonoma wine country, we’re seeing sprawl neighborhoods of single-family homes adjacent to fire-prone wilderness areas taking the brunt of the destruction.

Both types of disasters are going to become more common and intense in the coming years, as the planet warms even more. And that means we’re going to need to re-adjust our land development patterns with less sprawl and more infill.

Both types of disasters are going to become more common and intense in the coming years, as the planet warms even more. And that means we’re going to need to re-adjust our land development patterns with less sprawl and more infill.

In flood-prone areas, we’ll need more natural floodplains by concentrating development in the urban core and not allowing more sprawl. And in fire-prone areas, we’re going to need more defensible space between wildlands and sprawl, with more focused growth in our city centers that are protected somewhat from these fires by the urban ring.

How do we achieve these goals? Absent strong land use controls, such as urban growth boundaries and deregulation on local land use policies, we can achieve them through pricing. Examples include ending subsidized insurance for sprawl in flood- or fire-plains and levying higher fees on developments in these areas to cover the costs of the inevitable disasters.

Ultimately, more compact infill development and less sprawl will help make our cities and towns more resilient in the face of worsening climate change. It will take political will, perhaps motivated by these recent disasters, to get us there.

The impact of ride-hailing companies like Uber and Lyft on transit ridership hasn’t been clear. Anecdotes and personal hunch suggests that they’ve hurt transit ridership nationwide and increased driving miles.

The impact of ride-hailing companies like Uber and Lyft on transit ridership hasn’t been clear. Anecdotes and personal hunch suggests that they’ve hurt transit ridership nationwide and increased driving miles.

Now we finally have a study to document that impact, courtesy of UC Davis’s Institute of Transportation Studies. As the San Francisco Chronicle summarized:

•Urban ride-hailing passengers decreased their use of public transit by 6 percent. Bus and light rail service were both used less often by Uber and Lyft riders, while commuter rail saw a 3 percent bump in usage.

•Many ride-hailed trips (49 to 61 percent) would have not been made or would have occurred via walking, biking or transit.

“Ride-hailing is currently likely to contribute to growth in vehicle miles traveled in the major cities represented in this study,” the report authors wrote.

This is an important step in understanding the cause of falling transit ridership. It’s also an argument in favor of policy action, like congestion pricing and switching from the gas tax to a mileage fee to discourage extra car trips.

But fundamentally, transit agencies still need to do what they can to improve ridership, which includes requiring more development adjacent to transit stops and re-evaluating their fare structure and service network.