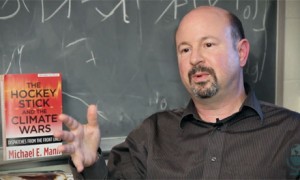

Dr. Michael Mann, one of the country’s leading climate scientists, has been harassed, threatened, and berated for his views that human actions are contributing to global climate change. But not just from anonymous commenters on websites — from leading publications like the National Review Online. After being compared to Jerry Sandusky and having the credibility of his work questioned, Mann finally has had enough. He is suing Rand Simberg of the Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI) blog and Mark Steyn at National Review Online for defamation.

So what is defamation and how do you prove it? To be sure, this is not my area of legal expertise. But the basics are fairly straightforward. As an overview, defamation means a public attack, based on false facts, on a person’s professional character or standing on an issue of public interest. The attacks have to cause damage to the plaintiff.

You can defend yourself against charges that you defamed someone by proving that you spoke the “truth.” You can also defend yourself by saying it was just an “opinion” as opposed to fact, although some jurisdictions have eliminated that distinction.

In this case:

Mann alleged that four phrases in Simberg’s post were defamatory: “data manipulation,” “academic and scientific misconduct,” “posterboy of the corrupt and disgraced climate science echo chamber,” and accusing the Penn State professor of molesting his data and thus being the “Jerry Sandusky of climate science.” He also cited a subsequent CEI press release that called his research “intellectually bogus.”

Trevor Burris of Forbes penned a full-throated defense of National Review and the other defendants, arguing that their words amounted to nothing more than name-calling:

While some of these phrases might be impolitic and unprofessional, they are not defamatory. Pugnacious rhetoric is still protected by the First Amendment, especially in matters of public debate.

Furthermore, he thinks the lawsuit will hurt the cause of climate change advocacy:

Proponents of the theory of catastrophic climate change should think twice before they support Dr. Mann’s lawsuit. In fact, anyone who engages in vigorous intellectual debate should be afraid that Mann’s lawsuit wasn’t immediately dismissed as a nuisance suit that is attempting to stifle First Amendment-protected speech. If Mann wins this lawsuit, he or his friends could easily find themselves on the other side of a defamation suit. Climate-change catastrophists consistently accuse climate-change “deniers” of intellectual and professional malfeasance.

I disagree. First, the comments against Mann aren’t just name-calling — they are name-calling to further false challenges to Mann’s work. They misleadingly call into question the accuracy of Mann’s research and methodology. In reality, there’s no real scientific debate on the overall facts. Sure, you can debate the scale of the warming and the precise amount of impact that human activity is having, but an astounding 97% of scientists have reached consensus on the overall issue. The courts should rightly investigate how factually plausible the challenges to Mann’s work are.

But should climate advocates be afraid of riding the defamation tiger, in case it turns around and bites them, as Burris suggests? I think there’s nothing to fear from judicial scrutiny if advocates label the fossil fuel-funded campaigns against their work phony and misleading. After all, a court wouldn’t sanction someone for calling people crazy who deny that smoking causes lung cancer or HIV causes AIDS. These are areas of broad scientific consensus with overwhelming supportive evidence. The link between human-caused greenhouse gas emissions and global warming is as equally supported.

Burris also seems to miss the point that this is a debate about science and numbers — not just values or general opinions. He cites Paul Krugman as potentially slanderous for calling Paul Ryan‘s budget a “fraud,” but Krugman has substantial evidence to back up his assertion that the Ryan budget was filled with misleading numbers that contradicted its stated effect. Like the Ryan budget, the dispute over Mann’s work is based on hard numbers, not intangible values or perspectives. Courts should be well-suited to see through these kinds of ideologically motivated, phony attacks.

Most importantly, from a purely strategic perspective, a court victory here would be a major public relations win for climate change advocacy. For climate deniers to lose in court would send the signal to the public that they are not to be trusted. That’s a great headline and PR win for climate change advocates, confirming a narrative that advocates have been emphasizing for years. Of course, a court loss for Mann could have the opposite effect, but given the facts, I think Mann may be on safe ground here.

I’m all in favor of a debate about climate science, but it can’t be a debate where journalists intentionally print misleading and false attacks based on transparently phony evidence. That stenography of lies is precisely the dynamic that sets back climate advocacy — and not this lawsuit.

Back in 2013, there was significant discussion about reforming the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), with the business community and its attorneys arguing that CEQA is nothing more than a litigation tool for opponents of new projects. Some environmentalists and labor unions countered that CEQA is necessary for decision-makers to adequately assess the environmental impacts of new projects and mitigate negative outcomes where feasible.

So of course the result of this debate was to streamline environmental review of a new basketball arena in downtown Sacramento.

But when California legislators passed SB 743 (Steinberg), they included an important provision related to CEQA review of project transportation impacts. Despite CEQA having an “E” for “Environmental,” transportation impacts basically meant auto-delay, or “Level of Service” (LOS). If your project slowed traffic anywhere, that was a negative impact, even if you were building a bus rapid transit line or new infill development that would reduce sprawl and traffic overall. Sprawl projects benefited, and infill and transit was penalized.

SB 743 directed the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research (OPR) to ditch this counter-productive LOS metric for something like a “vehicle miles traveled” standard (SB 743 gave OPR discretion to evaluate other metrics, too). OPR just released their draft proposal for the SB 743 guidelines and has settled on VMT.

Bus rapid transit shouldn’t get dinged for slowing cars

Why VMT? In short, the overall goal of our development patterns should be to provide housing, jobs and retail/services within convenient access of each other, without forcing long and frequent drives and creating more pollution. If we can reduce traffic overall, we’ve succeeded. VMT is the best and simplest metric to determine progress. Free VMT calculators exist, and many lead agencies already use it to calculate greenhouse gas emissions from projects.

Under the new proposed guidelines, OPR directs lead agencies to find less than significant transportation impacts if a project is located 1/2 mile from high-quality transit or in areas of less than the regional average for VMT. Local governments can set more stringent requirements if they want, but this will be the new floor. By 2016, OPR will phase in this standard across California, not just in infill areas.

The statute — and OPR — is basically trying to give infill projects a pass on transportation impacts under CEQA, while simultaneously dinging sprawl projects for creating more regional traffic. As Streetsblog LA observed:

When the state measured transportation impacts of a project based on car delay, it was fighting against its own environmental goals. Using LOS, it was easier and cheaper to build projects in outlying areas where individual intersections would show less delay resulting from new development. At the same time it was much harder and more expensive to build in dense areas where there was already a lot of traffic, and where measured LOS impacts would require expensive mitigations or reduced project size — but also where higher density would make transit, walking, and bicycling more viable transportation choices.

Planning expert Bill Fulton also noted:

Almost as bold as the proposal to switch to a VMT standard is OPR’s suggestion that expanded roadways in congested areas – currently often a mitigation under CEQA – should actually be examined as a possible growth-inducing impact under CEQA.

So while the focus now is on making infill projects easier to get entitled, the real action will be to slow or stop sprawl projects under CEQA, using the new VMT provision. Perhaps that’s why the big builders are worried about this change to VMT. In any event, the guidelines are not final, and OPR welcomes comments, which are due by October 10th. Yet while we can expect changes, the overall framework of VMT is unlikely to change, for the betterment of the state.

The fight over keeping transportation fuels under California’s cap-and-trade program is heating up. Assemblyman Henry Perea (D-Fresno) has an op-ed in the San Francisco Chronicle today arguing that delaying the fuels phase-in is a moral imperative to keep gas prices from rising:

Californians have a right to live healthy lives in a clean environment. But in areas like the Central Valley, people need to drive long distances, and thus would be affected disproportionately by rising gas prices. Delaying this action for three years to create greater public awareness and time for a more thorough discussion about viable climate change policy is not only responsible, but imperative to protect those most vulnerable.

But economist Severin Bornstein at the UC Berkeley Haas School of Business notes that the likely price increase for a gallon of gas will be 9-10 cents, which could be offset by the following consumer measures:

- Drive 70 mph instead of 72 mph on the freeway. That difference would improve your fuel economy by about 2.5%. The savings are much larger if you actually drive the speed limit.

- Buy a car that gets 31 MPG instead of 30 MPG. That will get you more than a 3% savings in fuel cost, more than offsetting the price increase.

- Keep your tires properly inflated. The Department of Energy estimates that underinflated tires waste about 0.3% of gasoline for every 1 psi drop in pressure.

The real motivating force for Perea’s efforts seems to be politics, and particularly the scare tactics of the oil and gas industry. As E&E Publishing reported last week (subscription required) from a Sacramento event on climate policies:

Assemblyman Mike Gatto (D) appeared in Perea’s stead and defended his position, saying that elected officials are under more scrutiny than appointees and have to respond to the will of the people as well as political pressures. If gasoline prices rise, Assembly members, who run for office every two years, will be punished, he said.

“We might recognize the price of oil is something that is set by the world commodity markets, but do the people understand this?” he asked. “If the price of gas spikes and the press picks up on it … and people start tying it into these regulations, it will not matter what the truth is.”

“They can’t vote [Air Resources Board Chairwoman] Mary Nichols out of office, but you know who they can vote out of office?” he asked.

Keeping transportation fuels under the cap will have significant benefits for the working poor as well as for the environmental and economic climate in California. Auction revenues from the program will fund public transit, low-carbon transportation options, and affordable housing, while the slight increase in gas prices may spur efficiency gains to reduce emissions that often harm low-income communities the most. Perea’s effort to delay the fuels phase-in is a step backward for all Californians, and I hope the legislature see through this counter-productive attempt to weaken California’s otherwise successful climate program.

California recently committed to spending $50 million on 28 public hydrogen fuel cell charging stations, throwing gasoline (bad pun) on the fire of a growing debate: electric vehicles vs, hydrogen fuel cells as the carbon-free vehicle technology of the future. California policy makers seem to think it may be both, based on their spending to support the two technologies.

But the evidence to date suggests that hydrogen fuel cells, which automakers like Toyota are committed to, may actually be “fool cells,” as Tesla CEO Elon Musk calls them derisively. Joe Romm, expert on alternative fuels from the US Department of Energy and author of a 2004 book on the debate, takes a strong position against hyrdogen fuel cells. His point? The fuel (hydrogen) will come from dirty sources for the foreseeable future, compared to clean, electric-powered battery vehicles:

Converting cheap fracked gas into hydrogen is very likely going to be substantially cheaper than practical, mass-produced carbon-free hydrogen for decades, certainly well past the point we need to start dramatically reducing transportation emissions (which is ASAP).

For EVs, on the other hand, unsubsidized renewable electricity is already directly competitive with grid electricity in many parts of the country — and poised to continue dropping in price. In places where carbon-free power is on the rise, such as California, the electricity is already far less carbon intense than the nation as a whole. That’s why EVs in a state like California is already super-green.

In terms of climate change impacts, Romm is clear:

So from a greenhouse gas perspective, there is no competition between pure electrics and hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles. EVs win hands down and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future.

I’m all in favor of fostering competition among promising clean vehicle technologies, but Romm’s critique points to the significant environmental disparity between these technologies, at least in the short term. In addition, there is a huge expense associated with developing an entirely new fuel infrastructure for hydrogen. EVs, by contrast, can access ubiquitous electricity throughout our developed areas. It’s also disappointing to see California commit to spending so much public money on a technology that consumers are not demanding, particularly given the ongoing need for investment in new EV charging stations in the state.

EVs certainly have a ways to go in terms of decreasing costs and increasing battery range. But automakers are making progress and consumers are responding. If companies like Toyota think hydrogen fuel cells are a better deal for California drivers and the environment, then let them spend their own money to prove it.

On the heels of my blog post last week about the growth in local PACE financing programs for clean energy, California is unveiling a massive 17-county PACE program today. As I discussed in the original blog post, PACE programs give building owners access to capital for clean energy improvements, such as rooftop solar and energy efficiency upgrades and appliances. The owners pay the money back as an assessment on their property tax bill.

In 2010, the federal government essentially quashed residential PACE with an unfortunate regulatory ruling calling into questions mortgages with PACE liens. However, today’s announcement represents a significant bounce-back for PACE. As the San Francisco Chronicle reports:

17 California counties will announce the launch of the nation’s largest PACE program yet, CaliforniaFirst. Backed by a new insurance fund created by the state, they are confident they can put the federal government’s concerns to rest. And cut energy use in the process.

“We always knew that this could be a very powerful tool to help people save energy and save money,” said Cisco DeVries, CEO of Renewable Funding, an Oakland company that will run CaliforniaFirst. “It’s exciting and it’s gratifying to see this come back around.”

The 17 participating counties represent 14 million residents, more than a third of California’s population. Bay Area counties taking part include Alameda, Marin, Napa, Santa Clara, San Mateo and Solano. San Francisco and Sonoma counties already have their own PACE programs.

The implications could be huge. Not only does it mean a lot more local energy efficiency improvements and economic savings, it means more local jobs, contributing to a growth industry of labor and business leaders that is becoming more politically powerful. It could also disrupt industries like solar leasing. After all, if you can buy your own solar array with semi-annual payments spread out over years that are less than your savings, why lease and not get the full value of the system?

Let’s hope this announcement will also encourage the feds to change their misguided policy, once they see their fears of mortgage losses will not materialize. Overall, it’s a good sign for California and the country.

California’s cap-and-trade program is an important part of the overall effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2020. The cap went into operation in 2012 with compliance required in 2013. So far, the program has generated close to a billion dollars in annual auction revenue from regulated sources that need to buy allowances to emit greenhouse gases. The cap is phasing in over time, and so far only large, industrial-type emitters and utilities are included.

That will change on January 1, 2015, when transportation fuel providers come under the cap. Or I should say “if” they come under the cap. The oil and gas industry is launching a big campaign to keep that from happening. They already won this two-year reprieve from the launch. At stake is a huge amount of auction revenue and a relatively small increase in gas prices that would spur innovation for more fuel-efficient vehicles.

That will change on January 1, 2015, when transportation fuel providers come under the cap. Or I should say “if” they come under the cap. The oil and gas industry is launching a big campaign to keep that from happening. They already won this two-year reprieve from the launch. At stake is a huge amount of auction revenue and a relatively small increase in gas prices that would spur innovation for more fuel-efficient vehicles.

Perhaps seeing the writing on the wall, State Senator Darrell Steinberg earlier this year proposed a preemptive retreat by removing fuels from the cap and creating a carbon tax as compensation. Environmentalists shot that proposal down, but they may now have a tough time keeping fuels under the cap. If they fail, they will be left with nothing, making Steinberg’s proposal seem like a missed opportunity.

Billionaire climate-fighter Tom Steyer is pledging to spend what it takes to keep fuels under the cap, according to the Los Angeles Times. Let’s hope he and the environmental community have success. Otherwise it will be a lot harder for California to meet its climate goals and encourage the technological innovation we need to wean ourselves off polluting fossil fuels in favor of cheaper, clean energy.

Energy efficiency upgrades and renewable energy arrays for homes and businesses pay for themselves over time through savings on the utility bill. But the big obstacle for many is finding the upfront cash. PACE (Property Assessed Clean Energy) programs overcame that barrier by allowing local governments to pay for this work and have property owners repay them via additional assessments on their property tax bills. Big win-win: communities get more energy efficient and clean energy neighborhoods, limiting pollution and creating good local jobs, while homeowners get access to low-interest financing.

But the federal agency that underwrites over half of the mortgages in the U.S. freaked out in 2010 over the program. The Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) put a stop to its rapid growth across the United States by telling property owners that they might jeopardize their mortgage if they take out a PACE lien. Basically the FHFA didn’t like the idea of local governments having lien priority on these payments in the event of a foreclosure, despite the numerous protections and safeguards included in the program. Since then, some PACE programs have continued, notably in Sonoma County and Riverside. California even created a statewide loan-loss reserve to protect federal interests, but it didn’t satisfy the feds.

Greentech Media now has a hopeful article on how PACE programs are rebounding from the federal hysteria:

It’s not illegal for homeowners backed by Fannie or Freddie to participate in the program. They are simply required to pay off the loan first if they move or refinance their mortgage. That may deter some homeowners from considering a PACE loan, but a lot of them are still making the decision to finance a retrofit through PACE.

Stacey Lawson, the CEO of Ygrene, another large PACE administrator, said in a previous interview that it all comes down to communicating the implications of taking on the loan: “There’s been a lot of fear, uncertainty and misinformation in the marketplace around the risk to homeowners. But it’s really just a simple business decision they have to make.”

Turns our PACE program administrators and homeowners are forging on, undeterred by the federal threats. This is good news for the climate fight and for the economy. And once the federal government reverses its stance (we can hope), the program should proliferate and become a top source for financing clean energy building improvements.

I just returned from a road trip through the Pacific Northwest, including Oregon (Cascades, Willamette Valley and Portland) and Washington (Seattle and the San Juan Islands). So of course I’m now an expert on the environmental trends there, as seen from the window of my car and my conversations with friends and strangers there. Based on this purely anecdotal evidence, I’ve compiled my list of top five environmental trends in the Pacific Northwest.

5) Farm-to-Fork: Lots of great agriculture in the Northwest, and they take advantage of it. Much of the food we ate on our trip, whether purchased at farmers markets, restaurants, or eaten at friends’ houses, came from hyper-local sources. At one cafe in the San Juan islands, all food was either grown at the farm on-site or traded/purchased from other local farms, including a nearby brewery.

4) Rail Transit: Portland and Seattle are undergoing a light rail construction boom. Seattle just recently began theirs, and we saw new tracks going in near the downtown, while Portland’s MAX system is extending south of the city. Plus Portland has a cool-looking (although I gather cost-ineffective) gondola tram linking two parts of their hospital complex that are separated by a hill.

3) Renewable Energy: Particularly in Oregon, we saw some innovative renewable energy arrays. Portland State University features the first solar “arch” that I’ve seen (photo right),

while another building in downtown had cool-looking wind turbines up top (photo left).

Bonus points for its energy efficient ventilation system through windows that can open to the street (remarkably unusual in most skyscrapers).

2) Infill Development: Portland and Seattle featured cranes galore on multistory apartment buildings near their downtowns. Seattle’s trendy Eastlake neighborhood and Portland’s Pearl District stood out to me for construction in these transit-friendly neighborhoods. One negative: Seattle’s Safeco Field baseball park has failed to stimulate much development in the otherwise industrial area south of downtown. I can only assume it’s a failure of planning and financing, but maybe it’s just not a great area for homes and businesses given the industrial activities going on.

1) Electric Vehicles: while California is still the leader here, Oregon features great signage for EV charging stations along the highway (see photo on the right).

Washington State also seemed to have a good presence of EVs on the road. We even saw a Tesla Model S on Orcas Island in the San Juans (an hour ferry ride from the mainland) with California plates! If that car wasn’t shipped there, then that’s a real coup for Tesla’s supercharger network along I-5.

Overall, it’s great to see other West Coast states making such progress on environmental and energy needs. One area of improvement: Washington State should definitely improve its tailpipe regulations — cars and trucks there are quite smelly and polluting. And of course we need both states to join California’s cap-and-trade market. But I’m confident that in the long run, the West Coast will help lead the country in smart policies to clean the environment and build a sustainable economy.

Greenhouse gas emissions from electricity production represent almost one-third of the total emissions from the United States. Today the Obama Administration finally used its authority under the Clean Air Act (required by a 2007 Supreme Court decision) to regulate this pollution. The Environmental Protection Agency set a proposed goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions from the electricity sector by 30% from 2005 levels by 2030. States will have significant leeway to meet these goals, including setting up cap-and-trade programs and using energy efficiency and natural gas to switch from coal.

I’m glad the president finally decided to take this step after Congress failed to pass a comprehensive federal approach and “cap-and-trade” and “climate change” suddenly became dirty words. Business groups and conservatives are already panning the proposed rules, but in fact they’ve already extracted significant concessions.

The biggest concession is that the baseline year is 2005. As a result, ta-da! We’re already halfway to the 2030 goal, because emissions fell 15% from 2005 to 2012. So we’re really talking about a 17% reduction. It’s not nothing but it’s unlikely to create the kind of reductions we need to avert the worst impacts of climate change, according to what scientists tell us. In addition, the rules will benefit from the retirement of many coal-fired power plants in the coming decades that were reaching the end of their useful lives anyway. They will likely be replaced by natural gas plants, due to falling natural gas prices and separate, stringent Clean Air Act regulations on new coal-fired plants. This process would have happened even without EPA action on carbon.

The economic impact is also negligible. The Chamber of Commerce predicted a doom-and-gloom scenario of $50B lost to the economy from these regulations by 2030. Of course, the Chamber is always wrong with these predictions. And as economist Paul Krugman pointed out, even if the Chamber is right, that’s only 0.2% of GDP in a $21.5T economy.

I wish Obama had used his Clean Air Act Authority more aggressively and much sooner, but better late and weak than never and nothing. It’s also important to lay the groundwork for future improvements to the system. For example, once state cap-and-trade programs are up and running under these rules, state leaders may incorporate additional greenhouse gas sources under the caps, possibly leading to a national program based on state-by-state groundwork and experimentation. And if it looks like we’re well on our way to meeting the 2030 targets sooner than expected, perhaps there will be political momentum to tighten the screws a bit more on the targets. Finally, the rules give the United States a tiny bit more credibility with other countries on climate change action when we sit down at the UN climate change conference in Paris late next year.

So overall, the new rules are a positive and long overdue step. Let’s hope they portend future action, both at the state and federal levels. Because by themselves, they’re not enough to get the job done.

Yes, federal cap-and-trade legislation went down to defeat in 2010, along with most of Obama’s progressive agenda. The once-Republican idea instead morphed into a political kill phrase for the right-wing, which they successfully branded as both taxation and regulation in one big ball of awful. But as Politico points out, cap-and-trade is actually alive and well at the state level, and it could be poised for expansion with EPA’s coming rule to reduce greenhouse gases from coal-fired power plants. California launched — and will be expanding — its program to reduce greenhouse gases, while nine northeastern states take part in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) trading program. As Politico notes:

Yes, federal cap-and-trade legislation went down to defeat in 2010, along with most of Obama’s progressive agenda. The once-Republican idea instead morphed into a political kill phrase for the right-wing, which they successfully branded as both taxation and regulation in one big ball of awful. But as Politico points out, cap-and-trade is actually alive and well at the state level, and it could be poised for expansion with EPA’s coming rule to reduce greenhouse gases from coal-fired power plants. California launched — and will be expanding — its program to reduce greenhouse gases, while nine northeastern states take part in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) trading program. As Politico notes:

Those ranks could grow because of EPA’s upcoming climate regulation, which is expected to give states wide latitude in how they reduce the greenhouse gas pollution from existing power plants.

If EPA, as expected, allows states to develop cap-and-trade programs to reduce carbon from their coal-fired power plant sector, then many states may begin setting up trading platforms that could go a long way to detoxifying the political attitude about cap-and-trade. And once the political opposition melts with the realization that the economy won’t crash with emissions credit trading, it will be politically and structurally easier to incorporate more sources under the cap. Eventually, with a strong network of states using cap-and-trade to minimize greenhouse gas emissions, the federal government may even find it politically safe to develop a national trading platform, with the state markets as a foundation.

Back in 2009, I opposed the cap-and-trade program developed in the federal Waxman-Markey bill because I thought it gave away too much to industry, while undercutting both California’s and EPA’s more promising efforts. While I’m disappointed the US didn’t act faster and better on climate change at the national scale, I’m hopeful that this state-by-state approach, prompted in part by long-overdue EPA action, and unfettered by the industry giveaways we saw at the federal level, will have a better chance of delivering sound policy and actual carbon reductions.