I used to think that the two critical governments working on climate change were China and California. China because its government leaders can snap their fingers and create a national carbon reduction program if they want. And California because of the state’s favorable political climate and history of business and technology innovation.

But I now must add Germany to the mix. The country has long pioneered pro-solar policies, with its generous “feed-in tariff” program (essentially a simple contract that pays a building owner cash for the solar power he or she generates). And of course its transit-friendly towns mean people there are less dependent on cars for mobility.

But as this New York Times article makes clear, Germany is in to win it on bringing down the price of renewables, including solar and wind:

Germany’s relentless push into renewable energy has implications far beyond its shores. By creating huge demand for wind turbines and especially for solar panels, it has helped lure big Chinese manufacturers into the market, and that combination is driving down costs faster than almost anyone thought possible just a few years ago.

As a wealthy, industrialized nation, Germany is well-positioned to lead the world in spurring the development of decarbonizing technologies. They’ve used their wealth for good purposes:

The program has expanded the renewables market and created huge economies of scale, with worldwide sales of solar panels doubling about every 21 months over the past decade, and prices falling roughly 20 percent with each doubling. “The Germans were not really buying power — they were buying price decline,” said Hal Harvey, who heads an energy think tank in San Francisco.

Of course, Germany and the rest of Europe have a huge amount to lose as the climate worsens. But whatever the motivation (and it seems out of genuine concern over carbon emissions), the world may soon be glad Germany it taking these steps.

As California faces an increasing need for more energy storage to integrate variable renewables and provide other grid services, used electric vehicle batteries could be a critical – and inexpensive – part of the solution. Sales of electric vehicles in the United States are heading toward a quarter million, with 100,000 of those purchases in California. The thousands of batteries that will be coming out of the vehicles in the coming years will still retain significant capacity, although not enough to provide a sufficient electric driving range. These used, less expensive batteries can be stacked and repurposed by utilities and building owners to clean the grid and reduce costs. Plus, electric vehicle customers could see lower upfront prices if automakers factor in the long-term resale value of the batteries in the sale price.

UCSD “second life” EV battery demonstration project. Courtesy of UC Regents/Rhett S. Miller.

UCLA and UC Berkeley Schools of Law, with the support of Bank of America, will be releasing a new report next Wednesday on policies needed to help boost this market. The report resulted from a one-day convening at UCLA Law that included major automakers, renewable companies, battery experts, and public officials.

On Friday, September 19th, from 10 to 11am, UC Berkeley Law will host a live webinar, featuring representatives of the Governor’s Office and the California Public Utilities Commission to discuss the report findings. You can register here (space is limited). I hope you can join.

This morning in Sacramento, former California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger journeyed back to his old stomping ground to highlight the state’s successes fighting climate change. He joined current governor Jerry Brown and a host of climate experts and business leaders to make the case for the 2015 Paris climate talks that California’s example can be replicated at an international scale.

But for all the dignitaries, politicians, and experts, there was actually very little said about the specific policies that seem to work in California. Nor was there discussion of any of the clean tech businesses that are leading the way to reduce greenhouse gases. Instead, it was a largely symbolic, self-congratulatory event, sprinkled with some useful facts and motivational talks.

First up, the former governator ran through the history of California’s climate fight since he took office, talking about how big business fought the climate agenda at every turn, claiming doom and gloom and seeking to overturn AB 32, the climate law, with a 2010 ballot initiative. “But Californians terminated it” at the polls, he quipped, “saying ‘hasta la vista baby’ to the oil companies.’ Later, Governor Brown echoed this sentiment about big businesses always crying wolf about environmental regulations, noting that Henry Ford himself even came to California to lobby against fuel efficiency standards in the 1970s.

Climate scientists followed, including UC Berkeley’s Dam Kammen and the Pacific Institute’s Peter Gleick. Gleick brought home the impacts of climate change on California when he noted that $100 billion worth of 2000-era buildings are threatened by sea level rise, which could displace 480,000 people living on the coastline and jeopardizing 10,000 megawatts worth of power plants, among other calamities.

A business panel followed, although not one with any of the leading clean technology companies. Former EPA head and now Apple Computers Executive Lisa Jackson described the “fun” and “opportunities” of fighting climate change at Apple with their net-zero data centers. Michael Britt of UPS acknowledged that the company is not afraid of higher gas prices under AB 32 and described internal combustion engines as an unsustainable “bridge” to cleaner technologies. The company will deploy 17 fuel cell trucks in the coming months at one-third the maintenance costs of traditional engines.

State Senate President-to-be Kevin De Leon then joined a panel where he discussed his efforts to include low-income Californians in the fight against climate change. His one million constituents live in a district criss-crossed by seven major freeways, and with 40% of the goods in the United States shipped through there, “a little girl’s lungs subsidize” the cheap purchases we make. Moderator Terry Tamminen noted that kids near the port in Los Angeles/Long Beach lose one percent of their lung capacity on average each year. De Leon felt that government should encourage more private investment in clean technologies, because “there isn’t enough public money” to do the job. He specifically cited the need for a stronger state infrastructure bank, one of the few specific policy needs discussed today.

Finally the current governor spoke, bringing laughs when he said that California’s environmental fight began with a Republican actor turned governor — Ronald Reagan of course, not Schwarzenegger. Brown’s point was that under Reagan and President Nixon, California secured a waiver in the federal Clean Air Act to go beyond federal standards, paving the way for California’s continued leadership on environmental issues. Ultimately, Brown described how we need to look to scientists and entrepreneurs to save us, while government can provide them the incentives.

Missing in the discussion today was exactly that: the businesses and the incentives. For example, no mention of Tesla, the California-bred company that is probably doing the most right now to bring down the costs of the technologies needed to clean our economy. And only a brief mention of the solar rooftop incentives in California and cap-and-trade, with nothing about California’s landmark energy storage law.

If California is going to make a case to the world about the policies needed to reduce carbon, we’ll need to do a better job than what our leaders did today. We can certainly brag about the broad goals California has set, and we should do so. But unless we can demonstrate the specific business and health advantages that the California program has brought, it will all seem pie-and-the-sky to outsiders.

In last night’s California gubernatorial debate, Republican candidate Neel Kashkari proposed a major reform to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), which requires environmental review of new projects. But rather than gutting CEQA completely, a la State-Senator-turned-Chevron-lobbyist Michael Rubio, Kashkari proposed to give all projects the same breaks that the Sacramento Kings received in last year’s SB 743 (Steinberg). As Kashkari explained:

When the Sacramento Kings were going to leave, and the NBA said we need a new arena…Governor Brown signed an expedited review, gave them a special deal… But instead of just giving it to those who are politically connected who can hire high-priced lobbyists, why don’t we actually adopt that new standard and make it available to everyone?

And from Kashkari’s website:

[A]ll projects that come under CEQA challenge should be afforded the same injunctive relief and expedited review process that the Sacramento arena warranted.

So what exactly did the Sacramento Kings get? As I described at the time:

SB 743 [gave] Sacramento Kings basketball arena proponents accelerated environmental review and immunity from injunctive relief unless the project is found to jeopardize public health, safety, or archaeological resources. In exchange for these benefits, the new stadium must meet strict environmental performance measures, including net-zero greenhouse gas emissions from passenger trips to the stadium, LEED Gold certification, and compliance with the sustainable land use plan for the region under SB 375. In short, basically the same performance standards required for $100 million projects under AB 900 (2011)

So the Sacramento Kings only received the injunctive relief and expedited review upon pledging to meet high environmental standards related to energy efficiency and greenhouse gas emissions. Somehow I don’t think that’s the standard Kashkari wants to apply to all businesses in California. First of all, it’s unworkable given the range of projects covered by CEQA (a transit line, for example, isn’t even eligible for LEED gold certification, which is limited to “buildings”). Secondly, it would ensure greater environmental protection, which Kashkari doesn’t seem to prioritize. Third, it would place a huge burden on the courts to expedite these projects, and Kashkari doesn’t seem likely to spend more money to boost their staffing to be able to handle the additional caseloads.

To echo the governor’s words last night, this “glib” proposal belies the true nature of the deal that the Kings received. Coupled with Kashkari’s plan to shift high speed rail bond funds to additional water storage projects (a move that would be illegal — not to mention a betrayal of the majority of voters who approved those funds in 2008 for high speed rail only), the candidate appears to be playing fast and loose with the facts, at least on environmental issues.

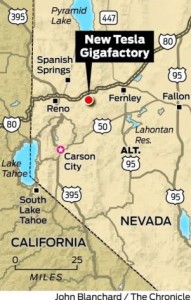

Some California environmentalists may be celebrating now that Tesla has apparently decided to build its $5 billion “gigafactory” in Nevada instead of California. Lawmakers here had toyed with the idea of weakening the state’s signature environmental law, the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), to help expedite review on the factory and therefore encourage Tesla to locate in-state, possibly in Stockton. But those plans fell through last week.

But Tesla’s decision could be an overall setback for the environment, compared to building a factory in California. To be sure, the idea of a gigafactory is a huge win for the environment overall. The cheaper batteries will encourage more adoption of electric vehicles and also help clean our grid by enabling inexpensive storage of surplus wind and solar energy.

So why is Nevada so bad, compared to California? First, the siting of the gigafactory will likely launch a major manufacturing program, with an attendant industry likely to spring up around it, in a state with much weaker regulation than California. Nevada ranked 20th among US states in a George Mason University survey of the most lax regulatory states when it comes to land use decision-making, with California ranked 49th. And a recent comprehensive survey of business owners gave Nevada an “A” on the impact of environmental regulations on business, which is not a good sign for environmental protection. California of course received an “F.” So the factory itself, as well as any future co-located suppliers, will operate with less future oversight for environmental health and safety protection.

In addition, the thousands of workers who will be employed there will likely end up in new subdivisions that sprawl over the high desert countryside, if Reno’s past growth is any indication. And they will likely commute to work by car, a lifestyle that Californians are rapidly abandoning. California meanwhile is engaging in regional transportation plans that will offer alternative, more environmentally friendly housing and transportation for workers, and its environmental laws are now encouraging growth closer to jobs and services.

Finally, from a shipping perspective, the factory in Nevada will have to transport the batteries by train to the major population centers in San Francisco and Los Angeles, which are the leading markets to buy electric vehicles. Locating the factory in Stockton would have reduced this shipping distance significantly, along with its associated environmental impacts, while placing the factory only a negligibly farther distance from the East Coast markets.

Tesla CEO Elon Musk has said that he plans to build more such factories. And as I say, the gigafactory is an overall environmental win. Yet while California’s economy would certainly benefit from locating it in-state, the environment would as well, compared to the site announced today.

The California Legislature passed SB 1275 (De Leon) last week, which would give the California Air Resources Board authority to eliminate the cash rebate incentive for wealthy people who buy electric vehicles. It would then use that revenue to increases the cash incentives for lower-income Californians.

I debated the merits of this approach on KPCC radio last month on the Airtalk program. My write-up of the debate is here. Meanwhile, Grist celebrates that electric vehicles won’t be “pretentious” anymore, as if the Nissan LEAF and Chevy Volt were glamor cars.

As I noted in my write-up, half of all Tesla Model S purchasers reported that the rebate made no difference in their decision. So why not use those funds for people who are truly on the fence without additional rebate money? The goal here for everyone should be to maximize the effectiveness of these limited rebate dollars and spur the greatest adoption possible of electric vehicles. The details will be figured out by agency experts, and that sounds fine to me. The governor has until the end of the month to sign.

Last year, the California legislature passed badly needed reform to change how agencies evaluate a project’s transportation impacts under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). The Governor’s Office of Planning and Research (OPR) was tasked with coming up with new guidelines for how this analysis should be done going forward. As I blogged about, the new proposed transportation metric, vehicle miles traveled (VMT), will inherently benefit infill projects and punish sprawl projects, because infill by its nature decreases VMT.

But you would never know that if you just read the misleading diatribe against the new guidelines by the influential large law firm Holland & Knight. Right off the bat, Holland & Knight attorneys get it wrong on both the legislation and the guidelines:

OPR proposes to dramatically expand CEQA by mandating evaluation and mitigation of “vehicle miles traveled” (VMT) as a new CEQA impact and single out certain infill projects as the first category of projects that must comply with this new VMT regime before it becomes mandatory for all projects in 2016.

In fact, the opposite is true. The guidelines essentially exempt any project within a half-mile of transit — or in areas that are below the regional average VMT levels — from any transportation analysis under CEQA. And lest you think that’s a small area, keep in mind that almost the entirety of urban Los Angeles is within a half-mile of a high quality transit stop, due to the extensive bus network.

A little less of this, please

What OPR is actually doing is eliminating the existing “level of service” (LOS) transportation analysis (which basically means auto delay) from CEQA in infill areas first and statewide by 2016. OPR is then replacing it with a VMT study requirement only in areas with high average VMT. Projects in low average VMT or transit areas either won’t need to do any transportation study whatsoever or won’t need to mitigate at all. That hardly equals an “expansion” of CEQA. Furthermore, the 2013 CEQA legislation specifically required OPR to come up with a replacement for LOS and called out VMT as the most likely substitute.

Holland & Knight attorneys then attempt to scare infill developers and their advocates by claiming that the new metric will lead to additional litigation. First of all, as mentioned, most infill projects won’t even need a transportation analysis under CEQA anymore, eliminating expensive and contentious traffic studies. Second, these traffic studies already trigger litigation all the time under the existing LOS transportation analysis, so it’s not like these guidelines are ruining the wonderful world for infill under the status quo. And finally, and most importantly, the OPR guidelines make lead agency decisions as bulletproof as possible on how to analyze transportation impacts under the new metric. How? By giving lead agencies discretion to pick the VMT model of their choice and to use their professional judgment in applying it to projects. LOS analysis certainly doesn’t have that kind of legal protection, as traffic studies are challenged all the time based on their methodology and assumptions.

But Holland & Knight attorneys protest that lead agencies lack affordable and easy-to-use VMT models, leading to more uncertainty:

[I]t must be acknowledged that we have few, if any, models that purport to be able to accurately characterize VMT at a project-specific level for infill projects. The absence of such models will lead to increased study costs (at a minimum) and litigation/enforcement uncertainty as “NIMBY” opponents will have a new tool to use in CEQA lawsuits aimed at stopping or delaying a project.

The reality is that agencies around the state are using off-the-shelf VMT models all the time, most notably for local climate action plans and for regional plans under SB 375. This is not a new field, and dozens of models exist for lead agencies to use their discretion to use.

Finally, Holland & Knight attorneys complain that the measures required to mitigate high VMT levels “go beyond CEQA’s statutory scope and delve into socioeconomic and land use policy planning issues that the legislature has repeatedly declined to include in CEQA.” I disagree. OPR’s suggested mitigation measures are sensible and targeted to reducing VMT, such as by improving access to transit, providing transit passes and bike-sharing, and reducing or unbundling parking. Ultimately, how else could a project with high VMT mitigate this impact? The goal here, after all, is to reduce driving and to use CEQA as a tool to encourage that reduction where feasible.

It’s unfortunate that Holland & Knight attorneys are attempting to spread this misinformation to their clients and beyond. The state needs to leave behind the old framework of prioritizing autos over transit, bicycling, and walking. At the same time, CEQA should require sprawl project developers to account for their impacts on regional traffic and air pollution. VMT is the most sensible metric to accomplish these goals, and OPR’s guidelines are well thought out, with opportunity for continued refinement from stakeholder input. Yes, it will involve a new framework and some getting used to. Yes, LOS will still exist in some local plans and agency analyses. But this is the beginning of a long overdue transition, and Holland & Knight should cease with the misinformation and let the state move forward.

The big fossil fuel companies wanted to avoid paying for the carbon pollution from their products via California’s cap-and-trade program. They tried to scare California residents about the looming gas price increases. They found an ally in Assemblyman Henry Perea (D-Fresno), who introduced AB 69 to delay including fuels under the cap. As I blogged about a few weeks ago, the money for the fuel pollution allowances would fund transit and electric vehicle programs, among other pollution-reducing technologies.

Now good news: State Senate President Darrell Steinberg prevented Perea’s bill from even coming up for a vote. That avoids the messy political problem of forcing legislators to weigh in on this issue during an election year. As I wrote about, the gas price increase is likely to be negligible, and there’s no reason oil companies can’t simply absorb the cost from their $200 billion annual profits, rather than passing it along to consumers.

Steinberg wrote a forceful letter to Perea explaining his logic, worth reading in full. So now fuels will come under the cap on January 1st, and California will use the revenue from the pollution allowances to fund the ongoing transition to a cleaner, cheaper and more sustainable form of transportation. And once under the cap, it will be difficult for the oil and gas interests to remove it later. Overall, this is excellent news for California’s fight to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and bolster our clean tech sector.

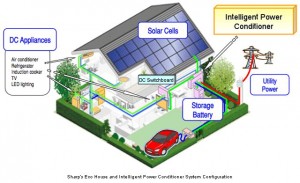

The best hope we have on Earth for averting the worst impacts of climate change is a pretty simple formula: a huge amount of renewable energy, with surpluses stored in technologies like cheap batteries, and all our transportation running on electricity.

Well, actually there’s another solution: we could de-industrialize and return to the Stone Age. Or humans could die off suddenly from disease or war. But I prefer the first approach.

The critical piece to this energy and transportation transition is bringing the cost of these technologies down, and two articles this week indicate that we’re making progress. First, solar prices have come down dramatically, leading to huge new demand which is now causing a shortage of panels. Analysts don’t expect solar panel prices to rise in response, but it is prompting companies like SolarCity to invest heavily in new solar PV production facilities. Underlying this dynamic is the fact that panels now sell for 76 cents a watt, compared with $2.01 at the end of 2010 (including a 12 percent price drop just this year).

The critical piece to this energy and transportation transition is bringing the cost of these technologies down, and two articles this week indicate that we’re making progress. First, solar prices have come down dramatically, leading to huge new demand which is now causing a shortage of panels. Analysts don’t expect solar panel prices to rise in response, but it is prompting companies like SolarCity to invest heavily in new solar PV production facilities. Underlying this dynamic is the fact that panels now sell for 76 cents a watt, compared with $2.01 at the end of 2010 (including a 12 percent price drop just this year).

Second, wind prices are falling, making wind energy competitive with natural gas in some parts of the country:

After topping out at nearly $70 per megawatt hour in 2009, the national average levelized price of wind purchase agreements fell to around $25 last year, the [U.S. Department of Energy] report sad. That means wind electricity costs about 2.5 cents per kilowatt hour, a highly competitive price in some parts of the country.

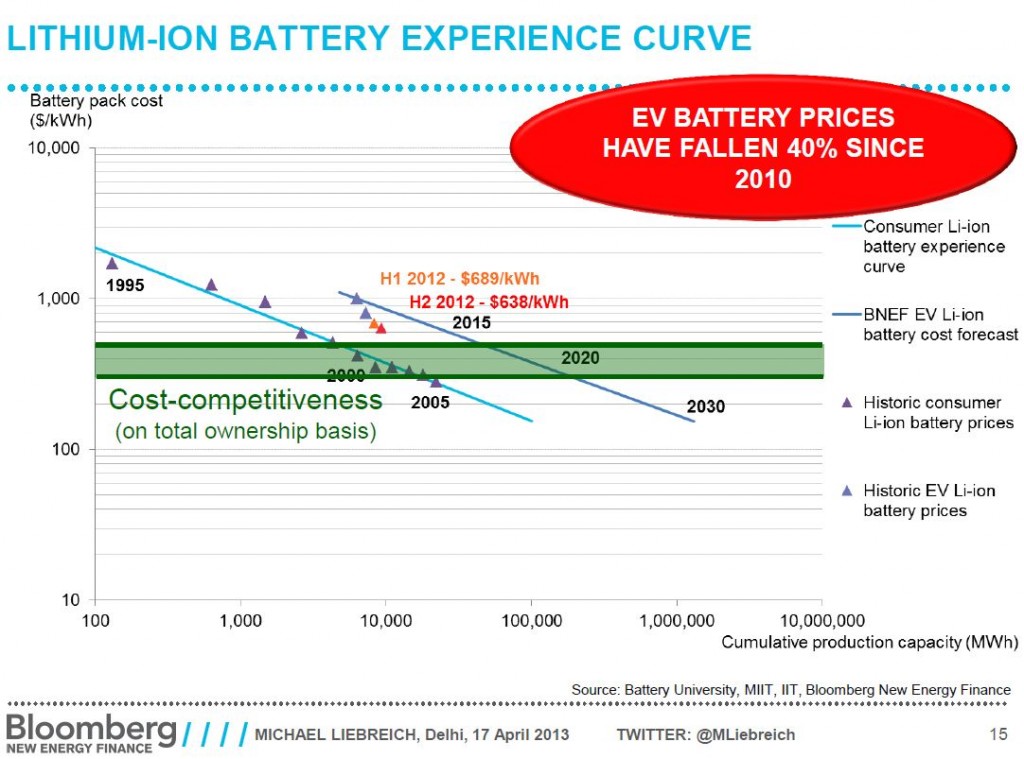

Finally, as I blogged about earlier this week, electric vehicle battery prices have dropped 40% since 2010.

This is all great news for the possibility of an economically painless transition to a sustainable economy. Credit so far is due to the private sector for the innovation and investment. But this is also a clear sign that government policies around the world to boost these markets are having success. On the solar and wind side, the federal government offers tax credits for investors, while many states have renewable energy mandates, financial incentives, and utility programs that reward customers for installing renewables. The federal government also provides a tax credit for electric vehicle purchases and loans and grants for clean technology startups (in some ways, the 2009 economic stimulus was Obama’s true climate change bill, given the support that legislation gave to game-changing companies like Tesla). And states like California offer cash rebates and other incentives for EV purchases, as well as a mandate for utilities to buy more energy storage.

Obviously we still have a long way to go, but the cost trends are very encouraging. And they should reinforce the political will to keep the incentives going while the private sector continues to do its part to bring down costs.

I posted a few weeks ago about the hydrogen fuel cell versus battery electric vehicle debate, citing alternative fuel expert Joe Romm’s evidence. Romm is back at it, highlighting the high costs and lack of environment benefits of hydrogen fuel cells:

The biggest problem hydrogen fuel cell vehicles face is that they deliver no obvious major consumer (or societal/environmental) benefit compared to the competition, but have a bunch of obvious consumer defects. These defects include high first cost, high fueling cost (compared to both gasoline and electricity), lack of fueling stations and lack of a nationwide fuel-delivery infrastructure — especially for renewable hydrogen.

Romm also describes the significant price decreases seen over the past few years in lithium ion batteries:

[M]assive amounts of money were poured into improving batteries and related components, not just by governments, car makers and clean energy venture capitalists, but also by portable device and phone manufacturers who wanted to improve performance while cutting costs. The results in the case of batteries have been impressive:

Between these highly encouraging battery cost reductions and the corresponding steep mountain to climb on hydrogen fuel cells, I continue to wonder why California just invested $50 million in this dubious technology.