Yesterday’s Superbowl featured two car commercials that couldn’t have been from more opposite ends of the spectrum. The first was from BMW, promoting its new all-electric i3. The spot features Bryant Gumbel and Katie Couric, circa 1994, discussing the internet like they were from a cave. Then they end up in 2015 discussing the all-electric BMW like they still live in a cave — making the point that new, transformative technologies take getting used to at first.

I like the spot because it makes that technology connection to EVs, although I think BMW could have played up the performance of the car rather than focus so much on the wind-powered BMW factory (who hasn’t heard of wind turbines? That’s an old technology). But it’s nice to see all-electrics get Superbowl attention (you may recall the plug-in hybrid Cadillac ELR ran a controversial spot last year). Here’s the BMW ad:

But then Jeep aired an ad for its Renegade SUV that was ultimately galling. Over a pensive rendition of “This Land Is Your Land,” it featured shots of beautiful spots around the world, including Southeast Asian waterways, redwood forests, and North African deserts. At the end, the message is: “The world is a gift. Play responsibly.” And then: “America’s smallest, lightest SUV.”

Only a car company would ask people to celebrate our natural world as a gift while it simultaneously burns the gases that are destroying it. Keep in mind that just 90 companies may ultimately be responsible for two-thirds of the greenhouse gases emitted since the dawning of the industrial age, and the big contributors are oil companies that exist in large part to fuel vehicles like the Renegade.

You can watch the Jeep spot here:

California is poised for a major energy transformation in the coming decades, with Governor Brown pledging to put the state on a path to 50% renewables and 50% less petroleum usage by 2030. Achieving this transformation will require a robust and thriving clean technology sector, including renewable energy and energy storage developers, energy efficiency contractors, smart grid hardware and software purveyors, and electric vehicle automakers, among others.

California is poised for a major energy transformation in the coming decades, with Governor Brown pledging to put the state on a path to 50% renewables and 50% less petroleum usage by 2030. Achieving this transformation will require a robust and thriving clean technology sector, including renewable energy and energy storage developers, energy efficiency contractors, smart grid hardware and software purveyors, and electric vehicle automakers, among others.

But to ensure the success of these industries, as well as a cost-effective energy transition for consumers, California must expand access to energy information. This information ranges from customer access to their long-term usage patterns in an easily-readable, standardized format, to utility statistics on distribution grid needs and pricing, to anonymized, aggregated energy usage patterns on a neighborhood scale. Customers can harness this information to use energy more efficiently, while clean technology companies can use it to improve their services, customer acquisition efforts, and competitiveness with traditional energy providers. Policy makers and nonprofit advocates could also use this information to target energy incentives to the customer groups and regions that would make the best use of them — thereby deploying limited public funds more cost-effectively.

To offer solutions for improved access to energy information, UC Berkeley and UCLA Schools of Law are today releasing the report Knowledge is Power: How Improved Energy Data Access Can Bolster Clean Energy Technologies & Save Money. The report resulted from a one-day gathering of clean technology leaders (including renewable energy developers, battery experts, smart grid suppliers, energy efficiency contractors, and electric vehicle automakers) and public officials. It is the fourteenth in the law schools’ Climate Change and Business Research Initiative, sponsored by Bank of America, which develops policies that help businesses prosper in an era of climate change.

The group identified barriers to expanded information access, from a lack of incentives and funding for utilities to collect and share data to concerns about compromising customer privacy and cybersecurity breaches. The report identifies information that would be most valuable to the clean technology sector and recommends that policy makers:

- Establish customers’ right to improved access to their own usage information through an easily organized, standardized format, including the disclosure of historic building energy audits;

- Develop cost-recovery mechanisms for utilities to collect and share aggregated, anonymized energy and market statistics to researchers and the private sector; and

- Fund the development and maintenance of secure energy information centers.

Most of these and other recommendations in the report will require action from state legislators and regulators, including via existing regulatory efforts at both the California Public Utilities Commission and California Energy Commission. Ultimately, by implementing steps like these, California can ensure a smoother and more cost-effective transition to a clean, efficient, and localized energy and transportation system.

Remember when oil companies cried last year about transportation fuels going under California’s cap-and-trade program in 2015? They tried to scare everyone about the “hidden gas tax” and how prices would rise 76 cents a gallon. As Bruce Maiman in the Sacramento Bee reminisces:

For months, the warnings were endless: Come January, gas prices would jump as much as 76 cents a gallon. “Put the brakes on the Hidden Gas Tax!” implored countless Facebook ads.

Anyone seeing pump prices skyrocketing?

Never mind that oil prices plummeted last year as a gallon of regular dropped in California from $4.13 last summer to $2.59 now – $2.48 in the Sacramento region. I’m sure most of the many thousands who hit the Facebook “like” button didn’t bother to investigate the California Drivers Alliance, or 15 other groups harping the same sky-is-falling message. A casual observer likely believed their claims of being a grass-roots group rising up against devious bureaucrats trying to sneak another tax past you.

In truth, what was hidden was the real identity of these front groups, all funded by the oil industry – the Western States Petroleum Association and the California Independent Oil Marketers Association, longtime opponents of Assembly Bill 32, California’s 2006 landmark legislation to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2020. The cap-and-trade system expanded this year to cover vehicle fuels.

Luckily for environmental advocates, the global oil glut has kept the political pressure off this issue, allowing California to greatly expand the cap-and-trade system.

Now let’s hope that advocates can use these big price drops to finally end the subsidies for oil and gas around the country, as the Economist called for today:

The most straightforward piece of reform, pretty much everywhere, is simply to remove all the subsidies for producing or consuming fossil fuels. Last year governments around the world threw $550 billion down that rathole—on everything from holding down the price of petrol in poor countries to encouraging companies to search for oil. By one count, such handouts led to extra consumption that was responsible for 36% of global carbon emissions in 1980-2010.

Falling prices provide an opportunity to rethink this nonsense.

To paraphrase Rahm Emanuel, never let a period of cheap oil go to waste.

With a name straight out of a WALL-E future, it’s ARPA-E, also known as the “U.S. Advanced Research Projects Agency – Energy” (don’t confuse them with DARPA-E, its cousin that focuses on defense).

Why is ARPA-E so important? Because this Department of Energy group is searching out and funding those moonshot — or sunshot — technologies that will give us the energy breakthroughs we need to fight climate change. If we’re going to find the better battery to finally wean us off oil and into electric drives, or build the cheap energy storage device to capture surplus renewables and truly decarbonize the grid, or make our solar panels even more efficient and cheap, chances are ARPA-E will be involved in making that happen. From its website:

Since 2009, ARPA-E has funded over 360 potentially transformational energy technology projects. Many of these projects have already demonstrated early indicators of technical success. For example, ARPA-E awardees have:

- Developed a 1 megawatt silicon carbide transistor the size of a fingernail

- Engineered microbes that use hydrogen and carbon dioxide to make liquid transportation fuel

- Pioneered a near-isothermal compressed air energy storage system

Technical achievements like these have spurred millions of dollars in follow-on private-sector funding to a number of ARPA-E projects. In addition, many ARPA-E awardees have formed start-up or spin-off companies or partnered with other parts of the government and industry to advance their technologies.

If I were in charge of the federal budget, I would fund this agency to the brim. So I’m pleased to see ARPA-E announcing another round of funding, this time for $125 million for “renewable and non-renewable electricity generation, transmission, storage and distribution, as well as energy efficiency technologies.” The funds can also go to transportation-oriented projects, including those focused on fuels, electrification, and energy efficiency. You can read more here.

While I know it’s a huge stretch to imagine happening, I hope this new congress supports the agency in the budget process. It just may be the best hope we have for finding and developing the technologies needed to truly solve climate change.

After Tuesday’s groundbreaking, Eric Holthaus of Mother Jones now decides high speed rail isn’t worth it anymore:

That $68 billion California plans to spend on its high-speed rail system could buy 82,000 state-of-the-art electric buses, 55 times Greyhound’s entire nationwide fleet. And they could start operating immediately. Dedicated bus lanes and congestion pricing have done wonders for reducing commute-hell in many cities, like London. There are ways to make intercity bus travel more appealing, too, as evidenced by the expansion of carriers like wifi-enabled MegaBus in recent years. Similar “curbside” buses are the fastest growing mode of intercity transport and are the most carbon-friendly way to travel medium to long distances in the United States.

He also recommends funding self-driving cars and regulating airplane emissions. He’s motivated by the urgency of climate change:

Given the incredible pressure that global warming is inflicting, we can’t waste precious resources on high-speed rail. It’s impractical to hope that truly high-speed rail—the kind that will compete with air travel—will arrive in time to do much good.

I appreciate Holthaus’s concern for time running out on the Earth’s climate and his willingness to search for low-cost, immediate transportation solutions. But his piece is misguided in slamming the decision to go forth with high speed rail.

I appreciate Holthaus’s concern for time running out on the Earth’s climate and his willingness to search for low-cost, immediate transportation solutions. But his piece is misguided in slamming the decision to go forth with high speed rail.

First, these aren’t “limited public transportation” funds that are being used. They are funds that were raised and dedicated solely for high speed rail. California voters in 2008 didn’t vote on a $10 billion bond initiative for 82,000 electric buses — they voted for high speed rail. Based on that political will, politicians in Washington specifically set aside stimulus funds for high speed rail (as well as electric vehicles) to help fund the system. And state politicians followed suit with cap-and-trade funds.

We can debate the wisdom of the voters and our leaders, but there’s no doubt that high speed rail is what they wanted, and they raised the funds to make it happen. In other words, high speed rail attracted its own constituency that found the funds for it. It’s not politically or legally feasible at this point to redirect those monies to other transportation forms, as Holthaus desires.

Second, there’s no reason why we can’t do what Holthaus recommends and still go forward with high speed rail. High speed rail doesn’t stop congestion pricing from happening, or more bus-only lanes, or regulation of airlines. California has an aggressive set of policies to encourage more electric vehicles, including buses. True, the cap-and-trade money that goes to high speed rail could have been used for other things. But it’s a relatively small amount of money, and a majority of those dollars go to other important greenhouse gas-reducing options. Even the stimulus, which is helping to support high speed rail, is also funding huge advancements in battery technology — which is critical for deploying more electric buses, cars, and grid storage.

Finally, Holthaus doesn’t engage with the potential greenhouse gas upsides for high speed rail. Most significantly, the system will divert the most polluting airplane trips as well as car traffic for a growing population that is already hemmed in by congestion and crowded airports. It will also entail a large investment in renewable energy to power the trains. Perhaps even more importantly, high speed rail could stimulate much more transit-oriented development in the Central Valley, which is otherwise susceptible to the same sprawl over its flat, agricultural-rich landscape that paved over the Los Angeles basin. The benefits of reducing per capita vehicle miles traveled in the Central Valley by providing an organizing infrastructure for more pedestrian and transit-friendly growth could be immense.

So while I’m sympathetic to the sentiment behind Holthaus’s arguments, I don’t think it’s fair to come out now and slam high speed rail. It’s going to happen, the money is there for it at this point, and we need to be thinking about a range of solutions to limit transportation emissions and not pit one technology against others. High speed rail is one important piece of the puzzle, and we should focus our efforts on making sure it gets built as efficiently for the taxpayers and climate as possible.

Jerry Brown was inaugurated today for his record fourth term as governor of California, and his address offered refreshing specifics on his environmental and climate goals:

In fact, we are well on our way to meeting our AB 32 goal of reducing carbon pollution and limiting the emissions of heat-trapping gases to 431 million tons by 2020. But now, it is time to establish our next set of objectives for 2030 and beyond.

Toward that end, I propose three ambitious goals to be accomplished within the next 15 years:

1. Increase from one-third to 50 percent our electricity derived from renewable sources;

2. Reduce today’s petroleum use in cars and trucks by up to 50 percent;

3. Double the efficiency of existing buildings and make heating fuels cleaner.

The 50% renewable standard by 2030 is the most striking of these recommendations, putting California on pace to lead the nation in renewable deployment (with Hawaii as a possible rival, given that state’s expressed goal of 65% renewables by 2030). As Berkeley and UCLA Law discussed in the November 2013 report Rewable Energy Beyond 2020: Next Steps for California, such a standard should be accompanied by a policy to ensure actual greenhouse gas reductions from the power sector. Otherwise, an increase in renewables could be offset by an increase in fossil fuel-based power, which might be needed to balance the intermittent renewables when the sun isn’t shining and the wind isn’t blowing — but demand remains high.

Governor Brown seems to acknowledge that risk when he called for specific measures to help ensure proper integration of these renewable power sources:

I envision a wide range of initiatives: more distributed power, expanded rooftop solar, micro-grids, an energy imbalance market, battery storage, the full integration of information technology and electrical distribution and millions of electric and low-carbon vehicles. How we achieve these goals and at what pace will take great thought and imagination mixed with pragmatic caution. It will require enormous innovation, research and investment. And we will need active collaboration at every stage with our scientists, engineers, entrepreneurs, businesses and officials at all levels.

Battery and other energy storage technologies (also detailed in this 2010 Power of Energy Storage report) are vital to balancing renewables on the grid by storing surplus renewable power for later dispatch. California is making great progress on deployment so far. And an energy imbalance market, linking renewable sources across the Western United States, as well as “demand response” technologies that encourage energy usage during times of peak renewables, will also help decrease greenhouse gases from the power sector as well as increase grid reliability and decrease costs.

Finally, the governor’s electric vehicle and energy efficiency goals represent the two other critical pieces in the effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions without having to return to the stone age. After all, it’s not enough just to clean our electricity sector — we need to electrify our transportation and be much more efficient with the energy we do use. All told, Governor Brown is reinforcing through policy the critical initiatives we need to grow the economy without overheating the planet beyond repair.

The next stage will be the administration’s goal for greenhouse gas reduction legislation for 2030 — a sequel to the AB 32 2020 goals. The governor set a timetable of March 2015 to unveil those targets, so we’ll stay tuned for that next big speech on the environment.

Here’s my take on the biggest environmental victories in 2014:

5. Continuing strength of the electric vehicle market. Sales are going well, new models are being introduced, and automakers are on notice that this trend isn’t going away. No technology is more important for reducing our greenhouse gas emissions than electric drives, so let’s hope the progress continues.

4. Transportation fuels stay under California’s cap-and-trade program. There was some debate about whether or not fuels would stay under the cap, given oil-and-gas industry machinations and legislative action. But the California Legislature stayed strong. Including fuels under the cap will mean more auction revenue for climate-fighting strategies and a statement that gas prices should include at least some of the cost of pollution. Nationally, it means California is showing how to make a cap-and-trade program work without hurting the economy, providing a model for other states and one day the nation.

3. EPA’s clean power rule. It was long overdue and probably too weak, but the Obama Administration developed a power sector rule that gives states flexibility to innovate in how they reduce emissions from power plants. That can include more renewables but also more energy efficiency (of course, all this assumes the plan doesn’t get gutted in the courts). As states respond, the price of renewables will decrease and states can start to share markets to make further reductions.

2. Continued solar energy boom. Prices of panels are falling, the efficiency is increasing, and solar is now becoming cost-competitive with fossil fuels in some areas. This technology is a crucial part of the solution to decarbonize the electricity supply and enable electrified transportation.

1. Climate agreement with China. While the specifics of the deal were very weak, it’s a major symbolic and psychological victory that can be improved over time. China is the major emitter of carbon in the world, and they have now committed themselves to reducing these emissions. That sets up Paris in 2015 for a potentially meaningful international agreement and also bolsters arguments to reduce emissions here in the United States.

Honorable mention: the advent of cost-effective, viable energy storage deployment in California.

Happy New Year! Let’s hope 2015 brings even more progress as we race against time on climate change.

The falling prices at the pump have been welcome news for drivers and consumers. It’s hard not to feel like gas prices are the ultimate determinant of our economic well-being. When they go up, the economy stalls, such as in the 1970s, early 2000s, and then the recent economic malaise following the Great Recession. And when they go down, the economy seems to hum, like in the 1990s and now with our increasingly robust economic recovery. Cheap energy underpins virtually everything we do, and transportation fuels are the key inputs for our industrial machine.

We know this industrial production and activity comes at an environmental cost. But is there reason to believe this time is different? There’s no doubt cheap gas means more pollution, at least in the short run. It’s encouraging less efficient vehicle purchases (SUV sales are up although electric vehicle sales so far are holding steady), more driving, and more economic activity that tends to produce more carbon emissions.

But there are environmental positives, some immediate and some more potential. In the immediate future, cheap oil means environmentally destructive oil and gas extraction methods, such as fracking, become too expensive to continue relative to the cheap global price of oil. The decrease in investment in these methods could have long-term consequences on supply, once this oil boom fades. And since these extraction methods often produce both oil and natural gas, the slowdown could drive up natural gas prices as a byproduct. That in turn could make renewables more cost-competitive and possibly discourage wasteful gas consumption, spurring efficiency overall.

But there are environmental positives, some immediate and some more potential. In the immediate future, cheap oil means environmentally destructive oil and gas extraction methods, such as fracking, become too expensive to continue relative to the cheap global price of oil. The decrease in investment in these methods could have long-term consequences on supply, once this oil boom fades. And since these extraction methods often produce both oil and natural gas, the slowdown could drive up natural gas prices as a byproduct. That in turn could make renewables more cost-competitive and possibly discourage wasteful gas consumption, spurring efficiency overall.

The other long-term potential environmental good is that a booming economy is a big factor in making voters more likely to support environmental measures (the so-called “affluence hypothesis”). So as many people experience rising income or more disposable cash from cheaper energy, environmental leaders should take the opportunity to solidify environmental policies. In California, that would mean legislating 2030 and maybe even 2050 greenhouse gas reduction goals to extend AB 32 (the state’s climate law) authority beyond 2020. That could also mean switching from the gas tax to a vehicle miles traveled tax to develop a more stable source of funding to repair existing roads and pay for new transit, pedestrian and bike infrastructure. Legislators could develop a permanent funding source to help build more affordable housing near transit. And it could also mean reforming Proposition 13 to allow local governments to raise voter-approved revenue for transit with a 55% majority.

At the national level, a booming economy could undermine efforts to rollback EPA regulations to reduce pollution from power plants, while correspondingly lead to more support for a nationwide vehicle miles traveled tax to fund transportation. (I’d love a national policy on carbon, too, but I don’t think that even a booming economy could overcome the structural impediments that disproportionately empower rural, fossil-fuel dependent states in the federal decision-making process.) And maybe a booming economy could make it easier for the Obama Administration to negotiate a more meaningful international climate treaty in Paris next year.

So the potential upsides of cheap gas are huge, while the known immediate downsides may be unavoidable. Let’s hope our environmental leaders capitalize on this opportunity while they have it. Because if history teaches us anything, it’s that cheap gas never lasts.

The article covers the debates raging over siting these large projects in pristine desert regions:

These projects are so big, they create their own ecologies and economies. “We’re not talking about a small project, we’re talking about a city the size of San Francisco,” says David Lamfrom, who runs the National Parks Conservation Association’s (NPCA) California Desert Program. “You’d just plop down a city in the middle of the wildest parts of the U.S.”

And these new wind and solar farms—cities, call them, since they aren’t like any farm you’ve seen—are only going to multiply in the coming years. The need for clean energy is expected to increase dramatically in the next decade, particularly after the U.S. and China recently announced a historic agreement to lower greenhouse gas emissions in their respective countries. At the core of the pact are two sets of commitments: The U.S. will lower emissions 26 to 28 percent by 2025 from the initial 2005 baselines, while China has agreed to set an emissions peak for 2030 and then commit to lowering emissions.

The piece also features some context-setting quotes from yours truly. Overall, I think it does a nice job describing what’s at stake, especially given the new international climate context.

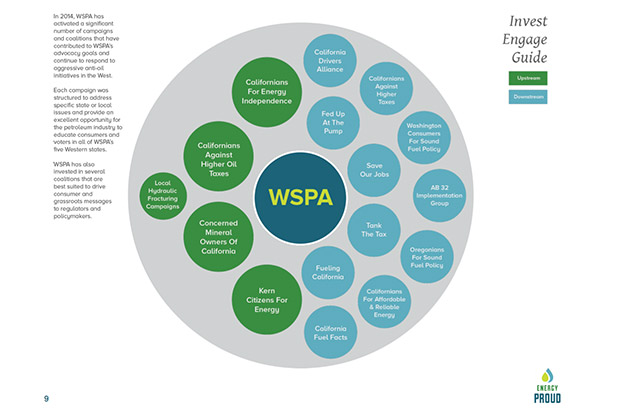

Whoopsie. The Western States Petroleum Association accidentally let slip its strategy document detailing how the oil and gas lobbying front seeks to undermine clean energy laws, especially California’s effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 2020:

Specifically, the deck from a presentation by WSPA President Catherine Reheis-Boyd lays out the construction of what environmentalists contend is an elaborate “astroturf campaign.” Groups with names such as Oregon Climate Change Campaign, Washington Consumers for Sound Fuel Policy, and AB 32 Implementation Group are made to look and sound like grassroots citizen-activists while promoting oil industry priorities and actually working against the implementation of AB 32.

It’s a similar strategy pursued by chemical interests, when they set up a fake firefighter group to keep in place California’s counter-productive flame retardant regulation, which retarded no flames while poisoning kids and firefighters alike when buildings burned.

It’s nice to see this approach exposed for everyone to see. The front groups have thankfully so far failed to motivate the public, but advocates should be wary of this tactic. In the right political climate, it could make a big difference in undermining public support for vital environmental laws. Here’s a hard-to-read chart from the slide deck of all the fake groups they fund (hard to read because they fund so many phony groups):