National Public Radio’s environmental reporter Abrahm Lustgarten investigates the history of the Colorado River water allocations and finds that bad policy is as much to blame as drought and climate change for the current shortages:

Lustgarten says conservation and increased efficiency in farming could reintroduce enormous quantities of water back into the Colorado River system. By Lustgarten’s estimate, if Arizona farmers switched from growing cotton to growing wheat, it would save enough water to supply about 1.4 million people with water each year.

But, Lustgarten adds, “There’s nothing really more politically touchy in the West than water and the prospect of taking away people’s water rights. So what you have when you talk about increasing efficiency or reapportioning water is essentially an argument between those who have it, which are the farmers and the people who have been on that land for generations, and those who don’t, which are the cities who are relative newcomers to the area.”

Notably, the area features one of the country’s largest coal-fired power plant at the Navajo Generating Station, dedicated almost exclusively to moving water around the Colorado River states. So the drought and water situation affects our energy supply and related pollution as much as anything. Re-examination of water rights, coupled with better financing mechanisms and rate structures, could therefore go a long way to solving both the water shortages and pollution from energy generation.

With more solar panels, internet connected home appliances, electric vehicles, and small-scale batteries, California will soon have millions of “distributed” energy resources it can tap into to make the grid more efficient and clean. The entity in charge of managing the grid just made it much easier to connect and aggregate these items as a bulk resource:

With more solar panels, internet connected home appliances, electric vehicles, and small-scale batteries, California will soon have millions of “distributed” energy resources it can tap into to make the grid more efficient and clean. The entity in charge of managing the grid just made it much easier to connect and aggregate these items as a bulk resource:

California is already busy creating new regulations and market structures to integrate rooftop solar, behind-the-meter batteries, plug-in electric vehicles and fast-acting demand response systems into its grid. This week, California’s grid operator took another step down this path — one that could allow these resources to tap the state’s grid markets as a revenue-generating resource, possibly as early as next year.

On Wednesday, the California Independent System Operator (CAISO) published a proposal (PDF) for creating a new class of grid market players, known as distributed energy resource providers — DERPs for short. In simple terms, the proposal sets rules for how DERs can be aggregated and dispatched to serve the same grid markets open to utility-scale energy installations today.

As the rules roll out and get refined, the state will become an international leader on integrating these resources into the grid, while providing owners of these assets with an additional revenue stream — further encouraging their deployment.

Former Representative Henry Waxman breaks down the options for the president’s final 18 months in office:

Former Representative Henry Waxman breaks down the options for the president’s final 18 months in office:

Executive authority, especially under the Clean Air Act, provides numerous paths for meaningful climate action. It can deliver popular, pro-growth, business-friendly pollution reductions that today are not possible through legislation. That is the legacy of one of our most important laws, and it can shape the legacy of this administration and the next.

Waxman goes on to list potential options to reduce emissions in aviation, cars and trucks, and other industrial sectors outside of electricity. It’s worth reading the whole thing.

I’ll be on Warren Olney’s show tonight at 7pm on KCRW Radio (89.9 FM in Los Angeles), discussing the Pope’s apparent bashing of cap-and-trade as a means to address climate change. Joining the roundtable discussion will be David Baker from the San Francisco Chronicle, who wrote an article describing the Pope’s comments, and Scott Edwards of Food & Water Watch, who doesn’t like cap-and-trade and was pleased with the Pope’s position.

Meanwhile, here’s what the Pope wrote to stir this particular issue up:

171. The strategy of buying and selling “carbon credits” can lead to a new form of speculation which would not help reduce the emission of polluting gases worldwide. This system seems to provide a quick and easy solution under the guise of a certain commitment to the environment, but in no way does it allow for the radical change which present circumstances require. Rather, it may simply become a ploy which permits maintaining the excessive consumption of some countries and sectors.

Hope you can listen in or stream. I’ll post a link later.

UPDATE: you can listen to the show here.

The Pope weighed in on Thursday with strong moral arguments in favor of addressing climate change. But in his landmark encyclical, he apparently bashed cap-and-trade as a means of addressing carbon pollution:

“The strategy of buying and selling ‘carbon credits’ can lead to a new form of speculation which would not help reduce the emission of polluting gases worldwide,” Francis wrote in his wide-ranging encyclical on the environment and global warming.

“This system seems to provide a quick and easy solution under the guise of a certain commitment to the environment, but in no way does it allow for the radical change which present circumstances require,” he wrote. “Rather, it may simply become a ploy which permits maintaining the excessive consumption of some countries and sectors.”

I have been a critic of cap-and-trade in the past, particularly the federal version proposed in 2009. The evidence to date for cap-and-trade at that point wasn’t great, with failed programs in Southern California and the European Union and a seeming success in the Northeast that had more to do with a technological fix than program design.

But I’ve been impressed with California’s efforts to implement it. First, it’s been executed well so far, with no apparent market manipulation and some real results in terms of emissions reductions. Second, it’s been an important backstop to other state climate policies, such as for renewable energy, low-carbon fuel, and energy efficiency. And third, it’s generated a lot of revenue (up to $4 billion this year) that will be used in significant amounts for pollution reduction in low-income communities, including for weatherization and affordable housing.

So why is the Pope a hater? My guess is that his criticism is more about the European cap-and-trade system, which did not work as planned and resulted in windfall profits for some sectors, particularly electric utilities.

I think if the Pope were to look closely at California’s program, he would come away with a better feeling about it. And in any event, California’s climate efforts involve much more than cap-and-trade. But to be sure, the program provides a critical safety net to ensure the state meets its 2020 greenhouse gas targets. It may not be as elegant as a carbon tax or as forceful as command-and-control regulations, but it will get the job done. And that should be worth some papal love.

A highly entertaining and informative (and long) read on the history of energy, climate, cars and Tesla by Tim Urban at “Wait But Why.” Elon Musk participated in the drafting of the post. I was particularly struck by this nugget on climate history:

18,000 years ago, global temperatures were about 5ºC lower than the 20th century average. That was enough to put Canada, Scandinavia, and half of England and the US under a half a mile of ice. That’s what 5ºC can do.8

100 million years ago, temperatures were 6-10ºC higher than they are now—and there were palm trees on the poles, no permanent ice anywhere, ocean levels were 200 meters higher, and this kind of shit was happening:

So we’re currently in this not-that-big window we probably should try to stay in:

I recommend reading the whole thing. Happy Friday!

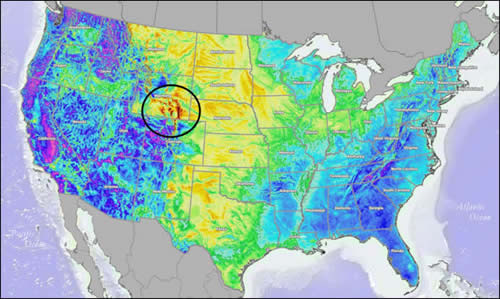

As California deploys more and more renewable energy, we’re going to have a problem integrating all that variable sun- and wind-powered electricity. One of the key solutions is to create a renewable energy market across the western United States. For example, if we need more morning renewable energy, maybe Arizona or New Mexico can export their solar power to us, since the sun will be higher there.

And if wind and sun are both down in California, maybe Wyoming wind can help us? Along those lines, the federal government just released a draft environmental review document for a transmission line to bring Wyoming wind power to California. It’s sad and ironic that Wyoming, a state heavily dependent on coal power and largely backwards when it comes to acknowledging climate science, will be exporting that clean energy anywhere but domestically.

Still, perhaps it will help ease a political transition in that state if locals in Wyoming realize there’s money to be made off clean energy. And for California, it means another step toward a deep decarbonization of our electricity supply.

But at the sub-national level, certain states within Germany are pushing the envelope even more. One of those states is Baden-Württemberg, led by the Green Party minister-president Winfried Kretschmann. Together with California, these sub-national climate hawks could play a powerful role at the upcoming UN climate talks in Paris.

Minister-President Kretschmann will be speaking at UC Berkeley’s Institute of European Studies tonight at 6pm at 100 Genetics & Plant Biology Building to discuss the climate synergies with these two subnational leaders.

In his lecture, he promises to make a “special announcement in the field of renewable energy and climate policy that will also affect California.” Let’s hope it’s something that will push the global community into action, instead of the wheel-spinning we’ve seen to date.

Big news in the climate world yesterday as California Governor Jerry Brown announced ambitious 2030 targets for greenhouse gas emissions for the state:

The target, contained in an executive order and expected to be folded into pending legislation, seeks to reduce emissions in California 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030.

The goal is in line with one adopted by the European Union last year, and proponents characterized it as the most aggressive in North America.

“With this order, California sets a very high bar for itself and other states and nations, but it’s one that must be reached – for this generation and generations to come,” Brown said in a prepared statement.

California is well on pace to meet our 2020 goals set forth by AB 32. But admittedly, we’ve had some winds at our back. The recession significantly cut energy demand and also seems to have reduced driving miles, although there could be multiple factors there. Cheap natural gas has also helped.

But make no mistake, California has encouraged significant progress on renewables and electric vehicle deployment, and is starting to make strides on energy storage as well. These will be critical technologies to meeting the governor’s 2030 goals. But the other big challenge will be the less sexy energy efficiency efforts, which so far the state has made only moderate progress on.

Still, with these goals, the path is now laid out for businesses, regulators and the public to follow. And California will provide a strong example for other states and countries by showing how to decarbonize the economy without hurting economic growth.