In an antidote to my doom-and-gloom post last week, Jonathan Chait tries to take the positive approach on climate change. He cites the rapidly decreasing cost of solar panels and other technological innovations, including battery storage, to make the case:

The energy revolution has rippled widely through the economy. In the first half of this year, renewable-energy installations accounted for 70 percent of new electrical power. As the energy mix has grown cleaner, people have found ways to use less of it, too. Incandescent bulbs have been replaced with efficient LEDs, in what Prajit Ghosh, director of power and renewables research at energy company Wood Mackenzie, refers to as a “total bulb revolution.” Tesla has introduced a new home battery, the “Powerwall,” and broken ground on a plant in Nevada, called the Gigafactory, with the capacity to churn out 500,000 lithium-ion battery packs per year, which will allow it to cut battery costs by a third and sell less expensive electric cars. And these are only today’s technologies. Laboratories from Cambridge to Silicon Valley are racing to develop next-generation batteries, as well as ultraefficient solar cells, vehicles, kitchen appliances. For more than a century, everything that consumed energy was designed without a thought to the carbon dioxide that would be released into the air. Now everything from buildings to refrigerators is being designed anew to account for scientific reality.

But he ultimately frames the progress as a race against time. Not against nature, but against Republicans taking over the federal government and getting the country to back-track on this progress.

Still, he thinks Obama has locked in much innovation, while UN negotiators in Paris may be able to hammer out the framework of an international deal. All of which puts us on a path to avoid the worst-case climate scenarios.

I share some of the optimism on the technology side, but there’s no denying that humanity has locked in some unpleasant changes in the coming centuries. Like the expression “all politics is local,” all environmentalism is local to some extent: many environmentalists have particular places on Earth that are special to them and that motivate their desire to protect the larger planet. So it can be depressing to think about how favorite places will change forever in the face of this global challenge.

But if Chait is right, we are actually responding pretty quickly with new innovation and policies to encourage it, and it’s worth focusing on that progress and how we can continue it.

Esquire reports on the deepening pessimism that many climate scientists are experiencing:

Among climate activists, gloom is building. Jim Driscoll of the National Institute for Peer Support just finished a study of a group of longtime activists whose most frequently reported feeling was sadness, followed by fear and anger. Dr. Lise Van Susteren, a practicing psychiatrist and graduate of Al Gore’s Inconvenient Truth slide-show training, calls this “pretraumatic” stress. “So many of us are exhibiting all the signs and symptoms of posttraumatic disorder—the anger, the panic, the obsessive intrusive thoughts.” Leading activist Gillian Caldwell went public with her “climate trauma,” as she called it, quitting the group she helped build and posting an article called “16 Tips for Avoiding Climate Burnout,” in which she suggests compartmentalization: “Reinforce boundaries between professional work and personal life. It is very hard to switch from the riveting force of apocalyptic predictions at work to home, where the problems are petty by comparison.”

Most of the dozens of scientists and activists I spoke to date the rise of the melancholy mood to the failure of the 2009 climate conference and the gradual shift from hope of prevention to plans for adaptation: Bill McKibben’s book Eaarth is a manual for survival on an earth so different he doesn’t think we should even spell it the same, and James Lovelock delivers the same message in A Rough Ride to the Future. In Australia, Clive Hamilton writes articles and books with titles like Requiem for a Species. In a recent issue of The New Yorker, the melancholy Jonathan Franzen argued that, since earth now “resembles a patient whose terminal cancer we can choose to treat either with disfiguring aggression or with palliation and sympathy,” we should stop trying to avoid the inevitable and spend our money on new nature preserves, where birds can go extinct a little more slowly.

While my expertise is on the law and policy side and not on the science, I can relate to some extent. You see enough studies and data about the inevitable and largely negative change that this planet will continue experiencing, and it makes for a nagging feeling of despair.

Maybe for that reason I actually enjoy working on the mitigation side of tackling climate change, as opposed to the adaptation or “preparation” side. With mitigation, we can focus on the technology solutions and the policies that enable them, offering some hope that we can manage the decline of our environment in a way that will still allow civilization to flourish.

And perhaps at some level, it’s important to have humility and perspective: Earth will still survive these climate changes, as the history of the planet has been one of great upheaval followed by rapid changes in evolution and redeployment of life. Some species out there now (maybe even some humans) will greatly benefit from these climate changes, and their descendants will probably repopulate the Earth like our mammalian ancestors did following the end of the dinosaur age.

But in the meantime, there’s not much else most of us can do other than trying to reduce carbon pollution through our policies and purchases.

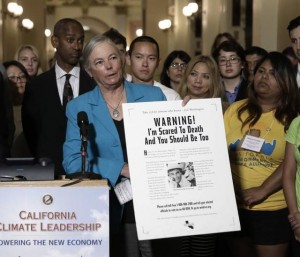

This legislative season in California will rank as a big disappointment for environmentalists. The last-minute failure to secure a 50% petroleum reduction by 2030 goal, followed by the defeat (actually postponing) of the bill to set 2030 and 2050 greenhouse gas reduction targets, was a major blow for environmentalists used to getting what they want out of Sacramento. Many commentators are starting to blame Governor Jerry “above the fray” Brown for not doing more to secure passage in the Assembly.

But lost in these setbacks is the major accomplishment of boosting California’s renewable energy standard to 50% by 2030, coupled with a mandate to double energy efficiency in existing buildings by that year. SB 350 (De Leon) may have been stripped of the petroleum goals, but these other targets are significant accomplishments. The energy efficiency piece set forth a process for the California Energy Commission to set long-term targets and evaluate progress on a regular basis, while the renewable energy mandate essentially just adds the 50% goal into the previous legislation requiring 33% by 2020 — in other words, no new process needs to be created for California to continue down this renewable path.

But lost in these setbacks is the major accomplishment of boosting California’s renewable energy standard to 50% by 2030, coupled with a mandate to double energy efficiency in existing buildings by that year. SB 350 (De Leon) may have been stripped of the petroleum goals, but these other targets are significant accomplishments. The energy efficiency piece set forth a process for the California Energy Commission to set long-term targets and evaluate progress on a regular basis, while the renewable energy mandate essentially just adds the 50% goal into the previous legislation requiring 33% by 2020 — in other words, no new process needs to be created for California to continue down this renewable path.

And finally, SB 350 makes it easier for California to develop a western regional market for renewables that will cover neighboring states and allow California both to import renewables from out-of-state when we need them and export our surplus renewables to other states. The legislation allows the California Independent System Operator, which essentially manages California’s grid, to change its governing rules to allow regional transmission operators to become part of the system. That will facilitate the import and export of renewables, helping California to better balance our in-state supply and ensure that dips in production don’t result in more natural gas-fired power.

So while the legislative season may have largely ended in disappointment, the accomplishments that did occur are worth celebrating for environmentalists.

In another, even bigger setback for the environmental community in California, SB 32 (Pavley), the bill to set greenhouse gas targets for 2030 and 2050, was pulled yesterday and will be tried again next year. The winners are the oil companies, who face tough regulations and competition from California’s climate efforts.

The failure is a big sting for climate advocates in the leading state on this issue. I’m not an expert on the politics, but it appears from press reports that the culprit was oil industry-funded opposition and concern from lawmakers that they won’t have much say in the implementation process. On this score, they are correct: AB 32 was a pretty amazing delegation of authority to the California Air Resources Board, with a bill that clocked in at just twelve pages, leaving the agency with wide rein to implement (compare that to the federal climate legislation back in 2009, which was over a thousand pages of legislated deal-making, rather than being a wide grant of authority to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to implement).

So what does the failure mean for ongoing climate efforts? Well, at the very least, we know AB 32 authority still controls, with the state on track to meet the 2020 targets. AB 32 also binds California to those continuing emissions levels beyond 2020, as Cara explained. So that means we’ll have at a minimum a flat-lining of emissions after 2020.

Beyond that authority, many (if not most) of the climate measures under AB 32 come from independent legislative acts, such as renewable energy and energy efficiency mandates (both of which may be strengthened if SB 350 passes today) and SB 375 (Steinberg) on land use, many of which have goals beyond 2020. Incentives for electric vehicles and other renewable fuel technologies will continue, along with federal efforts like the Clean Power Plan and fuel economy standards, plus tax breaks for solar and electric vehicles.

The governor has also issued an executive order that mirrors SB 32 with 2030 goals. But these orders can be changed by future governors, and they ultimately need to be based on legislated authority that may not be there beyond 2020.

Politically speaking, legislators will get one more go at this effort next year. Some say it’s tougher to pass in an election year, but the original AB 32 passed in an election year, and that was a non-presidential one when turnout was lower and presumably more conservative. Maybe SB 32 backers learned some lessons for the next effort.

There’s no denying that a failure in 2016, despite other ongoing measures to tackle climate change, could be a serious setback on reducing emissions — not just here in California but worldwide, given the state’s leadership role. But the state’s climate program will continue regardless. And as extreme weather continues and the benefits of the existing programs are felt by more residents, the politics may improve for these efforts as well.

It was a rare defeat yesterday for California’s environmental community. After major victories in 2006 with AB 32 (to reduce greenhouse gases to 1990 levels by 2020), 2008 with SB 375 (to reform transportation and land use planning), and in 2010 with a voter rejection of the oil industry’s attempt to roll back AB 32 (Prop 23), climate advocates were getting comfortable in the Golden State.

But the Western States Petroleum Association (aka “Big Oil”) trotted out a well-funded and dishonest ad campaign targeted at “moderate” Assembly Democrats, who gutted a provision of SB 350 that would have legislated a goal to reduce petroleum use in California by half by 2030.

So is this a major setback for the environment and public health in California? Well, maybe not. If the Assembly passes and the governor signs SB 32, the state’s effort to continue the progress on AB 32 out to 2030 and 2050, the California Air Resources Board could essentially require the same petroleum reduction goals through regulation. That agency would have broad authority to do so under SB 32, as it currently has under AB 32. Because transportation emissions are the largest wedge in the greenhouse gas emissions pie, the agency has to tackle petroleum fuels at some level to achieve the broader legislated goals.

So is this a major setback for the environment and public health in California? Well, maybe not. If the Assembly passes and the governor signs SB 32, the state’s effort to continue the progress on AB 32 out to 2030 and 2050, the California Air Resources Board could essentially require the same petroleum reduction goals through regulation. That agency would have broad authority to do so under SB 32, as it currently has under AB 32. Because transportation emissions are the largest wedge in the greenhouse gas emissions pie, the agency has to tackle petroleum fuels at some level to achieve the broader legislated goals.

And the state is already well on its way to achieving those goals anyway, thanks to federal fuel economy standards, improving electric vehicle technologies, and greater renewable biofuels deployment, as NRDC points out.

But the downside is real: having these goals legislated, as opposed to being in a regulatory form pursuant to a governor’s executive order, means they would have been more certain and fixed. Now a new administration could force changes to how the Air Resources Board regulates fuels, and Big Oil could use their influence during the regulatory process to water down or gut new rules. Plus, they can more easily turn to the courts to challenge regulations, resulting in delays and extra costs for the agency.

So it’s definitely a loss for the environmental community, but in the long run the path that California has to take is clear. Big Oil will see declining market share as vehicles become more efficient, people drive less, and as electric vehicles take hold. Their victory yesterday will probably be a temporary one.

The intermittent nature of renewables like wind and solar require grid operators to balance these resources without increasing costs and pollution from fossil fuel-based power. There are three main ways to do this: the first is energy storage, to store surplus solar and wind energy for nighttime or windless days. The second is demand response, or flexiwatts, to moderate demand based on renewable availability.

The intermittent nature of renewables like wind and solar require grid operators to balance these resources without increasing costs and pollution from fossil fuel-based power. There are three main ways to do this: the first is energy storage, to store surplus solar and wind energy for nighttime or windless days. The second is demand response, or flexiwatts, to moderate demand based on renewable availability.

But the less-discussed third option for states like California is to harness renewables from across the west.

James Bushnell (Energy Institute at Haas) and Benjamin Hobbs (Johns Hopkins University) describe the benefits of California expanding its “energy imbalance market” to cover renewables in other states. While some fret that the expansion could create governance headaches and possibly open the door to California importing dirty out-of-state coal power, they knock down these arguments and also discuss the huge benefits of an export market for California’s renewables:

There are triple benefits to being able to more easily export this excess power. First, it will actually lower costs for Californians by improving the efficiency of those other plants. Second, it will lower costs for other states because they can reduce output from their conventional plants. Third, air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions will go down because California plants will operate more efficiently while plants elsewhere will operate less.

The state is overdue for integrating its grid into the west in this way, and it’s encouraging to see California’s grid operator take steps to launch the expanding market.

Well, it doesn’t take a brain surgeon to figure out which industries stand to lose if California transitions to a low-carbon economy. Judging by the latest attacks on SB 350 and SB 32, sprawl developers and the oil industry are feeling a little panicked.

First oil. They sent out a deliberately misleading mailer claiming that SB 350, which seeks to reduce California’s oil consumption in half by 2030, will lead to gas shortages and higher prices. Under the fake pro-consumer-sounding group the California Drivers Alliance, they claim the following:

The Gas Restriction Act of 2015 (SB350) will restrict the use of gas and diesel by 50 percent. This law will limit how often we can drive our own cars. The state will also be collecting and monitoring our personal driving habits and tracking how much gas we use. They’re now reviewing regulations to force automakers to include data monitoring systems in all cars so that regulators will be able to penalize and fine us if we drive too much or use too much gas.

The Sacramento Bee then shot this lying fish in its barrel with a fact check:

The ad exploits a lack of specificity in Senate Bill 350 about what measures the California Air Resources Board could take to reduce petroleum use. But it misleads by suggesting gas rationing, surcharges and citations based on driving habits are in store.

Bottom line: California will be pursuing fuel economy measures, electric vehicles, hydrogen fuel cells and biofuels to meet these objectives — not gas rationing. With battery costs declining, battery electrics should be the dominant vehicles in production by then anyway.

Next comes big sprawl in the guise of the Building Industry Association. The BIA claims SB 32, to extend our greenhouse gas reduction goals to 2030 and 2050, will be an automatic “zero net energy” mandate, leading to an additional $58,000 in costs for each new housing unit, or a price increase of over 12 percent.

However, these numbers once again mislead. First off, the bill is no such mandate for new construction. The California Energy Commission will continue to develop new ways to reduce pollution from new buildings, but it will be on the same trajectory it’s been on for decades, which has saved Californians billions since the 1970s.

Second, most of the costs the BIA tallies are attributed to oversized, expensive solar PV arrays for each new home. Even if all new buildings had to have those arrays (which they don’t), prices will come down by 2030 significantly (80% in the last five years or so), while most neighborhoods would likely pool together on community solar rather than purchasing it individually. Finally, any increase in efficiency measures and solar will only save California residents in reduced energy bills.

For more on the BIA arguments, NRDC has a nice take-down here.

I guess it’s good news these industries are fighting back. If we have any hope of a cleaner, more prosperous and sustainable economy, it will only happen if these industries go the way of the fossils they help burn.

Well, it was bound to happen. With California’s renewable industry taking hold and prices declining, the broader pushback had to begin sometime. Sure, utilities and some ratepayer groups have been decrying renewables for a while.

Well, it was bound to happen. With California’s renewable industry taking hold and prices declining, the broader pushback had to begin sometime. Sure, utilities and some ratepayer groups have been decrying renewables for a while.

But now we’re seeing a new attack from conservatives: renewables will cause “energy poverty” by driving up electricity prices.

Here’s Terry Jones in Investors Business Daily:

California’s policies are, by current engineering and scientific standards, insane. Under its current rules, 25% of the state’s electricity consumption will have to come from renewable sources by 2016. It won’t happen, but it’s the law. By 2020, 33% will have to come from renewable resources. And if Gov. Jerry Brown has his way, it’ll jump to 50% by 2030.

Of course utilities will not meet the standard. But they will try. And doing so, says Lesser, will make electricity more expensive. “When retail consumers subsidize electricity supplies at above-market costs, retail prices inevitably rise, even if the fuel is ‘free,’ ” Lesser wrote. They already have: Since 2004, residential electricity prices are up by more than 30%.

What’s insane is that Jones doesn’t know that California is on pace to well exceed the 33% target by 2020, given all the projects in the pipeline. It’s also insane that Jones doesn’t acknowledge the remarkable price declines in solar (10-20% just last year).

Jones may have a point, however, that rates may increase to reflect the cost of incorporating these new energy sources. It’s unclear by how much, but we should keep in mind two things: 1) low-income ratepayers already are eligible for heavily discounted electricity and other utilities, so they will not be affected, and 2) eligible residents, including the working poor, can get solar on their roofs with no-money down, thanks to the proliferation of solar leases. Those panels can offset rate increases.

And in the long run, what’s the alternative? Keep relying on large-scale, low-employment dirty power, which often pollutes most in the poorest neighborhoods? Or keep pushing on distributed, job-rich solar and wind resources that produce power cleanly and ever more cheaply?

What’s more, the end game here could have a major upside for California’s poor. In addition to the solar jobs that can’t be outsourced and the energy savings from going solar, even with a solar lease, decreasing solar and battery costs means more and more Californians will be able to un-tether from the grid completely. We’re not there yet, but at this rate we’ll be there in the next few decades.

And when that day arrives for everyone, energy will be cheap, clean, and providing major job opportunities for the state that helped make it happen with its forward-thinking policies.

What in the world is going on in America? According to a global poll on climate attitudes, we are an outlier:

What in the world is going on in America? According to a global poll on climate attitudes, we are an outlier:

In the U.S. — unlike everywhere else — being better educated doesn’t guarantee that you are more likely to believe that climate change is a real thing that is actually happening. Instead, education seems to polarize in the United States: More education is correlated with greater concern about climate change among liberals and Democrats, and less concern from conservatives and Republicans. It seems that being better educated just means you have more ammo for defending the belief that your existing partisan identification bequeaths to you.

Although maybe I should be surprised that people in other countries actually allow new facts to change their minds. Either way, this should bolster the idea that we need to rely more on personal stories of climate impacts rather than citing evidence.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) will finally release its “Clean Power Plan” today to regulate carbon emissions from the power sector. The agency was required to do so by a 2007 Supreme Court decision. Yet due to what must be the brutal politics of trying to regulate coal-fired power plants, the Obama Administration dragged its feet until now — six years into the Obama presidency.

The final rules require a 32 percent drop in emissions by 2030 from 2005 levels. But this target is extremely watered down, to the point where it actually projects a slower rate of progress going forward on carbon emissions than we’ve been experiencing since 2005 to date, given that we’re already halfway to those targets with business-as-usual progress. Yet this is still better than the draft rules, which had targets so low that five states (!) were actually already in compliance with the 2030 goals.

Michael Grunwald pretty much sums it up in Politico:

If you’re really ranking them, the Clean Power Plan is at best the fourth-strongest action that Obama has taken to combat climate change, behind his much-maligned 2009 stimulus package, which poured $90 billion into clean energy and jump-started a green revolution; his dramatic increases in fuel-efficiency standards for cars and trucks, which should reduce our oil consumption by 2 million barrels per day; and his crackdown on mercury and other air pollutants, which has helped inspire utilities to retire 200 coal-fired power plants in just five years. The new carbon regulations should help prevent backsliding, and they should provide a talking point for U.S. negotiators at the global climate talks in Paris, but the 2030 goals would not seem overly ambitious even without new limits on carbon.

I couldn’t agree more with Grunwald on his rankings. The stimulus in particular is underestimated in its impact on boosting the clean technology sector. The sad part is that even this weak action today on climate will provoke endless litigation. And if a Republican wins the presidency in 2016, expect the EPA to gut and delay these rules and approve weak state implementation plans.

All relatively depressing, but these rules are still better than nothing. And maybe we can hold out hope that they will be strengthened over time.