If you want to hear about rail in Pasadena, come out tonight. I’ll be discussing the past and future of the Gold Line light rail to Pasadena and beyond, at the Downtown Pasadena Neighborhood Association’s annual meeting at 7:00 p.m. I’ll also cover Measure M on the county ballot and what it might do for a proposed Gold Line extension beyond the current terminus in Azusa. More info here.

And if you’re a lawyer in need of some environmental law discussion (and continuing legal education credits), come out tomorrow to the Los Angeles County Bar Association’s (LACBA) 15th Annual Environmental Law Fall Symposium: The Courts, the Climate, and the Deal: The Latest Developments. I’ll be on a panel discussing “Climate Change Regulation in California: 2020 and Beyond,” mainly focusing on the murky future of the state’s cap-and-trade program. That conference will be held tomorrow at the InterContinental Los Angeles Century City, from 11:30 to 4:3pm.

Hope to see you at one or both!

The presidential election next week is making most of the news these days, but while the rest of the country flirts with electing Donald Trump as the next president, California is going its own progressive way. The Republican Party has been all but completely marginalized in this state, mostly due to its anti-Latino rhetoric and policies from the 1990s that created a huge voter backlash from that growing segment of the population. In addition, the state’s more progressive metropolitan areas overwhelm voters in the more-conservative inland areas.

The state legislature briefly had a two-thirds supermajority of Democrats in both houses back in 2012. But scandals erased that margin in 2012 pretty quickly, with a few lost incumbents. In the end, not much came of it, policy wise.

So why does two-thirds matter? The number is significant because with two-thirds votes, the legislature can raise taxes and also put constitutional initiatives on the ballot without having to do an expensive signature-gathering effort. Otherwise, simple majority votes on revenues and constitutional initiatives are not sufficient.

Now Democrats have another chance at the two-thirds prize, if they can topple a few Republican incumbents with the big presidential-year turnout. What to do if they get it? Here’s my wish-list:

- Place a constitutional initiative before the voters to lower the voter-approval threshold for local transportation funding measures to 55%, from the current 2/3 requirement. 2/3 is a high bar for locals to attain. It usually results in overly compromised, watered-down measures that aren’t the most efficient use of funds but are necessary to achieve consensus support. 55% is much more reasonable.

- Replace the gas tax with a vehicle miles traveled fee. The gas tax is declining relative to inflation and as vehicles become more fuel efficient. As a result, California’s automobile infrastructure is crumbling and lacking sufficient funds from drivers. A mileage fee would accurately track how much wear drivers actually cause on the roads, plus it would help rein in incentives for sprawl, which autonomous vehicles could exacerbate.

- Re-authorize AB 32 (Nunez, 2006) and SB 32 (Pavley, 2016), California’s landmark 2020 and 2030 climate change laws. With a two-thirds supermajority re-approving those otherwise-majority approved measures, the Air Resources Board (the agency responsible for implementing the law) would be free to continue with its cap-and-trade program or even develop a carbon tax to rein in carbon pollution. Right now, the cap-and-trade auction is facing litigation because the legislature only approved the authorizing legislation by a majority vote. And a carbon tax is not legally permissible. Two-thirds votes would free the program of these legal challenges, particularly post-2020, and give the board more leeway on other carbon pricing mechanisms.

We’ll see what happens next Tuesday, and even with a super-majority it will be hard to keep the Democratic caucus unified. But if it can work, accomplishing these wish-list items would produce some major environmental wins for the state.

On Friday, Elon Musk unveiled a way to make solar panels as sleek and cool as Tesla has made electric cars. You can watch the video above, but it’s hard not to feel like this is the future of solar panels. The panels are broken down into tiles that (according to the video and photos) look pretty much exactly like real roofing material. According to Musk, they are also supposedly sturdier than everyday roofing material. In short, there’s no negative aesthetic impact from the panels, while you get a better roof in the process.

You can see photos here from Tech Crunch. And here’s the slate tile model, in the photo on the right. As you can see, it’s hard to tell that there’s any solar PV modules in there. It looks “real.”

You can see photos here from Tech Crunch. And here’s the slate tile model, in the photo on the right. As you can see, it’s hard to tell that there’s any solar PV modules in there. It looks “real.”

Musk made a point to say that the cost of the solar roof is less than the cost of a new roof plus electricity. That could be the case, but right now we don’t have any cost figures on the solar roof. We also know that the solar roof panels are not as efficient as regular solar panels (as the Tech Crunch article points out), and presumably any homeowner would be paying for panels in inefficient (i.e. shaded) parts of the roof. Plus, they wouldn’t be sized to the demand on-site, so customers may be paying for too much solar production compared to the retail credit they can get to offset their usage.

And of course, how many people are replacing their roofs in any given year? If the average roof lasts 25 years, that means just 4% of the market, and probably less given that many people are renting or living in multi-unit dwellings without access to their roof.

But Musk knows that the incentives around rooftop solar are diminishing across the country. As his PowerWall battery gets cheaper, solar customers are going to want to bundle solar with storage, effectively making any utility credit system pointless. After all, why be dependent on regulators giving you retail credit for any surplus solar you generate, when you can just use all your solar energy on-site as you store it for nighttime and cloudy days in your battery?

So lots of unanswered questions, but one thing is clear: solar panels just became sleek and cool — something you couldn’t necessarily say before Friday.

Ever since California was invaded in the nineteenth century and eventually absorbed by the U.S., our land management practices have been atrocious. Mining and lumber companies went to work clear cutting most of the forests, including even rare giant sequoias, using the wood for mine shafts and other infrastructure.

Then, compounding matters, land managers have actively suppressed forest fires, leading to overgrown forests ripe for catastrophic fires and now intense tree die-offs due to drought and climate change.

Contrast this to Native California land management, which involved regular burns that cleared out the forest understory and left giant, well-spaced trees to thrive.

Now a new UC Berkeley study documents how controlled fires can provide all sorts of benefits for forest health and water supply:

“When fire is not suppressed, you get all these benefits: increased stream flow, increased downstream water availability, increased soil moisture, which improves habitat for the plants within the watershed. And it increases the drought resistance of the remaining trees and also increases the fire resilience because you have created these natural firebreaks,” said Gabrielle Boisramé, a graduate student in UC Berkeley’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and first author of the study.

You can see more in the video above from the San Francisco Chronicle.

Meanwhile, the forests in the central and southern Sierra Nevada are experiencing an unprecedented pine tree die-off, due to the drought and climate change, as I mentioned above. Had these forests been managed properly, the pine trees would not have been able to grow back in water-competing clumps and might have been better able to withstand the drought.

Below is a photo I took from Yosemite National Park last weekend, where towering dead pines are going to be cleared out soon, leaving the area almost unrecognizable, and perhaps permanently altered. Let’s hope this situation motivates more responsible forest management practices going forward (tree thinning and controlled burns), as well as a stepped up fight against climate change.

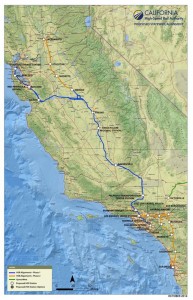

California’s high speed rail system has been moving at a low speed since voters approved a bond issue to launch it in 2008. That ballot measure authorized a bullet train from San Francisco to Los Angeles and eventually Anaheim, at speeds of 220 miles per hour and stops in Central Valley cities like Fresno and Bakersfield. The total trip time would be no more than 2 hours and 40 minutes between the two big cities, at fares less than airplane travel.

California’s high speed rail system has been moving at a low speed since voters approved a bond issue to launch it in 2008. That ballot measure authorized a bullet train from San Francisco to Los Angeles and eventually Anaheim, at speeds of 220 miles per hour and stops in Central Valley cities like Fresno and Bakersfield. The total trip time would be no more than 2 hours and 40 minutes between the two big cities, at fares less than airplane travel.

The rationale for the system is that it will provide a cheaper way to move a growing population around the state than expanding airports and highways. It will connect the relatively weak economies of the Central Valley with the prosperous coastal cities, providing an economic boost, all while enabling low-carbon transportation and promoting car-free lifestyles for communities connected to the system.

But since 2008, legal and political battles have slowed the system’s progress, as everyone from farmers in the Central Valley, wealthy homeowners in the San Francisco peninsula, and even equestrians in the hills above Burbank have fought to push the route away from their land. It’s local NIMBY politics on a statewide scale.

These legal and political challenges have in turn created funding headaches for the system. The original price tag of $40 billion ballooned to a projected $118 billion, before a revised business plan reduced it to an estimated $62 billion, as described in the 2016 business plan. Of that amount, the 2008 bond issues provides almost $10 billion, federal funds provide another $3.3 billion, and cap-and-trade funds may provide another few billion. System backers hope the rest come from private sources, but so far none have stepped up.

With strong support from the governor, the state was able to dedicate 25% of cap-and-trade auction proceeds to high speed rail construction. But the auction faces legal uncertainty going forward, due to a pending court case brought by the California Chamber of Commerce. An adverse verdict could mean that the money will halt either immediately or post 2020.

Meanwhile, the federal government has been unusually stingy with this infrastructure project. After Republicans took over Congress in the 2010 midterms, the federal dollars dried up, leaving the state to fund the project on its own. Only the 2009 stimulus provided some federal money for the train, but nowhere close to a match for the state contribution. By comparison, the federal government typically contributes 50% of the money for urban rail systems and between 90 and 100% for highways.

The funding picture has now affected the route design. The initial connections were going to be from the Central Valley to somewhere north of Los Angeles, hooking into the commuter Metrolink train to deliver passengers to Union Station in downtown Los Angeles. Now there’s not enough money to get the train through the Tehachapi mountains that separate Southern California from the Central Valley. So the initial connection will now go to San Jose from the Central Valley, with a link to the commuter Caltrain to get passengers to San Francisco. High speed rail bond money will then pay for upgrades to Caltrain and Metrolink, to prepare those systems for eventual high speed rail connections.

So with all the controversy and politics for this important project, I look forward to interviewing California High Speed Rail Authority chair Dan Richard tonight on City Visions, on NPR affiliate 91.7 FM KALW radio in San Francisco, from 7-8pm. For those out of the area, you can stream it or listen to the archived broadcast after the show here. I’ll ask Dan for more information on the funding, politics, and current construction status. And listeners are free to call in or email with questions. Hope you can tune in and ask your questions about the system’s future!

When people want to act to limit climate change and reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, solar panels, LED bulbs, and electric cars may come to mind. But an often overlooked step is changing your diet.

Meat production worldwide is a major contributor of greenhouse gases, particularly red meat. Cows emit methane, but they also require a ton of feed (usually corn) that in turn requires a lot of fertilizer produced from natural gas. Some studies indicate that you can make a bigger impact reducing your carbon footprint simply by avoiding meat consumption — even more than driving a hybrid.

Meat production worldwide is a major contributor of greenhouse gases, particularly red meat. Cows emit methane, but they also require a ton of feed (usually corn) that in turn requires a lot of fertilizer produced from natural gas. Some studies indicate that you can make a bigger impact reducing your carbon footprint simply by avoiding meat consumption — even more than driving a hybrid.

So leave it to Silicon Valley to address the challenge. A number of startups are figuring out alternative, cleaner ways to produce meat from plants, per the San Francisco Chronicle:

Impossible Foods, based in Redwood City, is one of two California companies racing to build a beefless burger so good that it fools carnivores. Impossible Foods’ Impossible Burger debuted in one New York restaurant in July and arrives in California this week. The company’s rival, Beyond Meat, has produced a Beyond Burger that is on sale in Whole Foods stores in the mountain states and may make it to the Bay Area by the end of the year.

Most manufacturers of processed food market their products as if they’re one cardboard box away from grandma’s best dish. Not Impossible Foods or Beyond Meat. Their methods are nakedly high tech. Their funding comes from tech-sector investors. And though both companies are emitting a tremendous amount of hype in the food world, their intended audience isn’t the organic-minded or even the vegetarian. Like most of Silicon Valley’s unicorn aspirants, Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat say they’re out to change the world.

If Silicon Valley can “science the hell” out of meat production (to paraphrase Matt Damon in The Martian), it would be a major win for the environment. Convincing people not to eat meat is an almost impossible sell, and as more of the world industrializes, meat consumption is only increasing.

Sure, policy makers might be able to tax meat enough to discourage consumption, or meat prices may rise so much that it achieves the same effect, but that may be politically difficult or simply take too long. So it would be much better if we could instead provide people an alternative that tastes just like the real thing.

A guilt- and emissions-free burger? I for one certainly wish these companies well.

In Fortune, former Tesla VP Cristiano Carlutti dishes on the company and the upcoming Model 3 (Tesla’s first mass-market EV, due in 2017):

As far as the downsides of the Tesla Model 3, let’s try to look at things from a different perspective: the biggest downside of Model 3 in my opinion is that it doesn’t exist yet. Lots of things can change until the launch date and I would assume that, when it was presented earlier this year, Model 3 was probably nowhere near a decent stage of development.

In order to understand this perspective, you have to take a different look at the way the company operates: in my opinion, it’s fundamentally a very focused marketing machine that until now has been focused on selling shares, with car sales instrumental to that. Before some fans attack me because of this comment, let me tell you that… it was the right thing to do!

In other words, Elon perfectly knew since the beginning that he would need a massive amount of money to become a car OEM and that, in order to raise that money, he had to create and sustain excitement in investors even more than in clients. Another way to look at it is that at this prices, the purchase of Tesla stock is more irrational than the purchase of a Model S: the latter is a very good car, competitive in its market, while the stock is more of a bet (or a gamble) on future dividends that nobody knows if they will ever appear. Car sales and car fans are just instrumental to raise the money Tesla needs to reach the point where it will be self-sustainable: the gamble is that financial markets keep drinking the company’s kool-aid at least until the company becomes self-sustainable. If they stop drinking it too soon, it will be game over and an historical failure, if believers sustain the company long enough, it will be a masterpiece of entrepreneurship and a tremendous success.

A lot is at stake with the future of Tesla. The company is, in my view, the most important private sector clean technology purveyor out there. Elon Musk has almost single-handedly pushed EVs to the forefront of the public imagination, spurring other automakers to follow suit. He also is betting big on energy storage and its marriage with solar PV, which will be essential to decarbonizing the grid. Combined with electric transportation, Tesla’s technology deployment promises to help the world decarbonize at a much greater rate than we otherwise would.

I don’t want to overstate it, but Tesla is making a strong claim to being in position to quite literally save the world (at least from out-of-control climate change).

So we need the company to succeed and raise the capital it needs for the deployment it envisions. If Carlutti is to be believed, let’s hope Musk can keep stoking the imagination of investors — and more importantly, that he and his team can deliver on their big promise with the Model 3. They’ll need a car that meets expectations at the right price and delivery time, without some of the quality issues plaguing the Model S.

It’s possible to do, but not certain. Reason for us all to be nervously optimistic.

In the effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, glitzy technology like solar panels and electric vehicles get a lot of attention. But often times there are some simple and relatively cheap technologies that can make just as much difference, particularly when looking at the costs.

Energy efficiency measures are a great example. Conserving energy is just as powerful, if not more so, than buying emissions-free energy like solar power. But it’s much cheaper. Case in point: updating your cable box to take advantage of new efficiency features can save you a lot on your utility bill.

Energy efficiency measures are a great example. Conserving energy is just as powerful, if not more so, than buying emissions-free energy like solar power. But it’s much cheaper. Case in point: updating your cable box to take advantage of new efficiency features can save you a lot on your utility bill.

Now David Roberts at Vox.com flags another promising technology: the heat pump.

A heat pump is a “mechanical-compression cycle refrigeration system” that can serve as both a furnace and an air conditioner (indeed, many air conditioners are just one-way heat pumps). From manufacturer Trane:

Even in air that seems too cold, heat energy is present. When it’s cold outside a heat pump extracts this outside heat and transfers it inside. When it’s warm outside, it reverses directions and acts like an air conditioner, removing heat from your home.

Because it merely moves, rather than generates, heat, it is far more efficient than combustion furnaces.

They key feature for our purposes is that heat pumps run on electricity. When Siemens modeled shifting 80 percent of citywide heat consumption over from natural gas to electric heat pumps, emissions declined another 14 percent…

Switching natural gas appliances to electric will be critical in the long term to reducing emissions from buildings. Right now, most furnaces and ranges are natural gas powered, but heap pumps can make the transition to electric heating much easier. Then when you combine it with emissions-free electricity such as from solar power, you’ve suddenly got a major climate win.

My guess is that with the right policy-based incentives (rebates and cheap financing), we could greatly spur consumer adoption of these technologies and ultimately bring the price down as economies of scale kick in. It would be a big win for the climate and potentially a cost-effective use of our resources.

Self-driving cars are already here. Automakers and software companies are testing them like crazy, and people like Elon Musk predict that they could be the norm within a decade.

There’s a lot to like about the technology: it can potentially make car accidents a thing of the past, allow us to avoid the pain and stress of driving and instead do something productive with that time, and potentially free up a lot of space in our built environment that is presently dedicated to parking cars, particularly if we switch to on-demand type ownership models (the “Netflix of cars” approach).

But from an environmental perspective, there’s a huge potential downside. If driving is made easy, the technology could encourage more driving and therefore more traffic. Just imagine how convenient it might be for people to live far from their jobs if the commute can involve a robot driving for them while they nap or work on a laptop.

So what can policy makers do to head off this dystopia? The solutions look a lot like what we need to do to address traffic and sprawl anyway, even without the new technology taking over:

- First, we should stop investing in highway expansion projects and instead use available dollars to maintain existing roads and highways. We shouldn’t build more capacity to accommodate endless self-driving traffic, which will only encourage more sprawl and congestion.

- Second, we should build more alternatives to traffic, such as bus-only lanes, bike and pedestrian infrastructure, and rail transit. When we do build highways, we should include congestion pricing features, with the revenue reinvested in mobility options for that corridor. With viable and plentiful alternatives to driving, people won’t opt for self-driving cars as readily.

- Finally, and most importantly, we need to price transportation better to reflect the true costs. If people truly want to live far from job centers and use self-driving to navigate long commutes, that’s fine. But they should then pay for the costs to us all from the increased traffic and environmental degradation. That means switching from a gas tax to a vehicle miles traveled, or fee-per-mile, tax. As cars get more fuel efficient and transition to battery electric models, gas tax revenue will decline. Self-driving car owners will then need to help pay for the infrastructure they’re using.

There are other policy options to consider, but these three would be a great start to heading off a potential nightmare scenario of self-driving traffic and sprawl misery. And in the meantime, we can encourage the environmentally positive features of self-driving technology by encouraging more car- and ride-sharing business models and the development of “right sized” vehicles that fit the vehicle size to the trip.

In the end, it’s always better to be prepared for the future than overwhelmed by it.

Last night’s presidential debate was a real low for American democracy, with the audience cheering Donald Trump’s threat to jail his political opponent, Hillary Clinton, once he’s elected. Members of the media seemed to highlight the shocking claim almost in passing, perhaps because they don’t quite realize that they’d be next in jail.

Last night’s presidential debate was a real low for American democracy, with the audience cheering Donald Trump’s threat to jail his political opponent, Hillary Clinton, once he’s elected. Members of the media seemed to highlight the shocking claim almost in passing, perhaps because they don’t quite realize that they’d be next in jail.

But aside from these chilling words, there was actually a bit of substantive discussion in the debate, too. The second-to-last question on energy policy in particular caught my attention. Trump answered first, and Grist helpfully broke down the amazing amount of falsehoods in his reply:

• Trump: “[E]nergy is under siege by the Obama administration. … We are killing, absolutely killing, our energy business in this country.”

In fact: Total U.S. energy production has increased for the last six years in a row. The oil and gas sector has been booming during the Obama presidency, as have the solar and wind industries. Coal companies have been struggling — but that is largely not the fault of President Obama, just as the oil boom is largely not something he can take credit for.

• Trump: “I will bring our energy companies back. … They will make money. They will pay off our national debt. They will pay off our tremendous budget deficits.”

In fact: There is no remotely credible economic analysis to suggest that Trump’s proposals for expanded domestic fossil fuel extraction would generate enough additional tax revenue to close the budget deficit, much less pay off the existing national debt. It’s particularly implausible when you consider Trump’s massive tax-cut plans that would make both the deficit and debt considerably larger.

• Trump: “I’m all for alternative forms of energy, including wind, including solar, etc.”

In fact: Trump’s energy plan offers nothing to increase solar or wind energy production, but instead focuses on boosting fossil fuels.

• Trump: “There is a thing called clean coal.”

In fact: The hope that coal plants’ carbon emissions can be drastically reduced — either through technology that captures and sequesters the emissions or that converts coal to synthetic gas — burns eternal for the coal industry’s cheerleaders. But no one has actually significantly cut emissions at an economically viable coal plant. The promises of “clean coal” projects have not been fulfilled.

• Trump: “Foreign companies are now coming in and buying so many of our different plants, and then rejiggering the plant so they can take care of their oil.”

In fact: What is Trump trying to say with this gibberish? We have no idea.

But lest we automatically assume Clinton’s answer pleased the environmental community, she made two comments that raised some hackles. First, she described natural gas as a “bridge” to cleaner fuels, which many environmentalists dispute due to the methane and other emissions involved. Second, she described the United States as “energy independent” when we’re still a net importer of crude oil and petroleum.

Still, the candidates are miles apart on this issue, as my colleague Dan Farber describes on Legal Planet, with Clinton the only real choice for those who care about the environment.

This is not a typical election with the usual policy disagreements among the candidates. Instead, it’s a race between two major party candidates with vastly different levels of respect for our American democracy and values. We shouldn’t overlook that fundamental difference, but we should also still use the occasion to talk about important issues like energy — and note the stark differences among the candidates’ views.