I finally had a chance to watch actor Leonardo DiCaprio’s “Before the Flood” documentary on climate change, and it’s a well-done and gripping look at what’s in store for our planet if we don’t act. The actor has made addressing the issue a top personal crusade, and it shows in this film.

The visuals are stunning and alarming, and he spends most of the film meeting with climate scientists, activists, and political and business leaders, from President Obama to Elon Musk to the Pope. His questions to Obama in particular seem even more poignant now that Trump, a climate science denier, is set to be the next president.

You won’t learn a lot about climate science as with Al Gore’s “An Inconvenient Truth,” but Before the Flood touches on the big picture science points and describes the most pressing impacts, including sea level rise, drought and crop failures, and a shutdown of the North Atlantic ocean current with continued ice melt.

In terms of solutions, the big ones preached by the film include eating less meat, buying fewer foods with palm oil, and supporting a carbon tax. Musk also has screen time discussing his battery factory and the need for energy storage. Other solutions are mentioned at the end, such as supporting renewables and keeping fossil fuels in the ground.

DiCaprio is an effective messenger on climate, despite the risk of another Hollywood actor taking on a cause: he’s pessimistic but honest about the situation and aware of his hypocrisy on the issue as a global jet-setter. He also narrates the film effectively, putting climate change in a near-biblical context without explicitly saying so.

The movie is free to watch on National Geographic television, Amazon, and other outlets, and it’s well worth your time.

California’s transportation infrastructure has been steadily declining for years, a victim of neglect from dwindling gas tax revenue. As a result, local governments have been raising their own taxes to fund needed repair and expansion. But these efforts can undermine environmental goals by encouraging driving and more sprawl.

As the state’s just-released 2030 draft scoping plan for greenhouse gas reduction makes clear [PDF], reducing vehicles miles traveled (VMT) is essential to achieve sustainable growth and emissions in California:

While the majority of the GHG reductions from the transportation sector in this Discussion Draft will come from technologies and low carbon fuels, a reduction in the growth of VMT is also needed. VMT reductions are necessary to achieve the 2030 target and must be part of any strategy evaluated in this plan. Stronger SB 375 GHG reduction targets will enable the State to make significant progress towards this goal, but alone will not provide all of the VMT growth reductions that will be needed. There is a gap between what SB 375 can provide and what is needed to meet the State’s 2030 and 2050 goals. More needs to be done through continued land use changes, synergies with emerging mobility solutions like ridesourcing, and changes in travel behavior, especially among millennials.

Transportation investments can either encourage or reduce VMTs, if they go to automobile infrastructure instead of walking, biking and transit projects.

Now that Democrats have a super-majority in both houses of the legislature, they should prioritize new transportation spending in VMT-reducing investments. The best way would be to replace the gas tax with a mileage-based fee, with the revenue going only to maintenance of existing infrastructure and new VMT-reducing projects. The necessary two-thirds vote for that revenue is now possible, at least in theory.

In the long run, it could be the most important environmental legislation for the state to come out of this session of the legislature.

I’m a big believer that islands will lead the way in decarbonizing the economy. Many of them have ample renewables resources, such as geothermal on Hawaii’s Big Island and Iceland, wind and hydro on Kodiak Island, and solar energy on other Hawaiian islands.

Now, on the heels of the big Tesla-SolarCity merger, the American Samoa island of Ta’u used the companies’ products to go 100% renewable. As the Washington Post reported, the island’s leaders wanted to stop depending on expensive, imported diesel fuel to generate electricity:

“[They] basically just put out a solicitation to see if anybody could provide an alternative to diesel, and that’s something that we responded to,” said Peter Rive, co-founder and chief technology officer of solar provider SolarCity, which was recently acquired by Tesla.

The result is a system composed of more than 5,000 SolarCity solar panels and 60 Tesla Powerpack battery storage systems. The new microgrid could save the island nearly 110,000 gallons of diesel fuel each year, which amounts to about 2.5 million pounds of carbon dioxide emissions, according to data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

The microgrid is already up and operating, according to Rive, and covering about 99 percent of the island’s power needs. The battery system can provide three full days of power to the island without sun, he added. And it can fully recharge in seven hours of sunlight.

It may have been easier for this island to go 100% renewable compared to other places, given its ample sunshine and small population. I’m assuming the island lacks energy-intensive industries as well. But the lessons can be applicable to other islands and economies, particularly when you factor in other generation technologies, like wind and hydropower.

Now if Ta’u just switches to all battery-electric vehicles, they’ll pull off the full eco-paradise.

It’s been a guessing game since Election Day about what Trump will do on climate change and renewable energy. Some renewable advocates believe the bipartisan support for solar and wind will inoculate current federal tax credits from getting rolled back. Others believe that the tax credits will be vulnerable in the event of a big congressional overhaul of the tax code. Meanwhile, Trump has surrounded himself with climate science deniers and oil-and-gas tycoons.

But one “clean” energy technology might get favored treatment: nuclear fusion.

Why? One of Trump’s most ardent backers, Peter Thiel, the Silicon Valley billionaire, is a big proponent and investor, as Bloomberg News reports:

Nuclear fusion, which would harness the power of the sun without all the nasty byproducts, is a long-shot—politically, financially, and technologically. Despite relative ambivalence toward fusion by the Obama administration, research has continued apace internationally, and in the American public and private sector. At the head of this pack are venture capitalists like Peter Thiel, the Silicon Valley billionaire who spoke at the 2016 Republican National Convention and is said to be working on the Trump transition team. He has funded a fusion start-up called Helion Energy through his Mithril Capital Management to pursue the ultimate dream of environmentalists the world over.

Fusion has sounded interesting on paper but has never materialized as a practical option. Of course, solar panels used to be prohibitively expensive and impractical until government incentives and pro-manufacturing policies spurred the necessary investment to bring costs down. Thiel’s company is hoping for the same dynamic with fusion:

Helion hopes to make a fusion generator that’s 1,000 times smaller, 500 times cheaper, and 10 times faster than more conventional, massive projects, according to its website. The company is building a “magneto-inertial fusion” generator. It produces power by injecting heated hydrogen and helium at high speed (a million miles an hour) into a “burn chamber,” where a strong magnetic field compresses the plasma to a temperature high enough to initiate fusion. Energy from the reaction is used to generate electricity.

Meanwhile, a potential ally, pro-nuclear environmentalist Ted Nordhaus, is causing a stir with a post arguing that the clean energy industry shouldn’t rush to deal with the Trump Administration given its authoritarian leanings, even if it pursues policies in their interests:

Trump campaigned and won the election fair and square. He has every right to pursue his agenda and vision for the country. When and if it becomes clear that democratic norms will prevail in the new Administration, that Trump does not intend to prosecute his political opponents, squelch dissent, and harass the free press, I will happily praise the Administration when it takes actions that I believe to be consistent with health, prosperity, equity, and environmental protection, and criticize it when it does not.

But the signals have thus far been mixed and that presents complicated decisions for those of us in think tanks, advocacy organizations, and the media. Most of our professional incentives are to act as if some version of normal democratic discourse and policy-making will prevail. There is not much for us to do, at least in the normal way that advocates advocate and analysts analyze, in the event that those norms do not prevail. The risk for all of us is that in our haste to get back to normal politics and advocacy, we normalize a dangerous turn toward authoritarianism.

Lots to chew on for an industry (one of many) now facing complicated and challenging times.

Michael Barnard at Clean Technica is bullish on global climate action, despite the Trump electoral college win last week:

Michael Barnard at Clean Technica is bullish on global climate action, despite the Trump electoral college win last week:

There are multiple reasons for this, but it comes down to inertia and isolationism. International and internal US agreements are hard to unwind, often bipartisan, and won’t be focus areas. The economics of wind and solar are transforming generation globally. Electric vehicles have multiple value propositions besides climate change. The rest of the world and especially China aren’t going to stop, they’ll just pull ahead of the USA. And a military that stays home doesn’t burn nearly as much diesel and aviation fuel. There’s no reason to cheer for a Trump presidency if you care about the climate and the global economic impacts of climate change, but there’s less reason for gloom than most would think.

He also makes a similar argument that I made last week, that a likely economic downturn caused by Trump policies could slow emissions.

I’m less optimistic than Barnard about what Trump will do to the Paris accord, but his point about clean technologies is an important one. Have these technologies, like renewables and electric vehicles, reached the economic tipping point to be viable even without federal tax credits and other support?

I’m reading mixed things. Utility Dive reports on the optimistic case:

“Our industry will be fine,” Sunnova CEO John Berger told Utility Dive. Sunnova is one of the leading national rooftop solar providers. “Business models will change and the companies that can’t deliver a better service at a better price won’t make it.”

Losing its 30% federal investment tax credit (ITC) might even provoke constructive change, Berger said. “But with or without the ITC, this industry will thrive and that is because we are quickly driving down the cost of solar and solar components and now the cost of batteries is coming down as fast.”

And yet Greentech Media forecasts some major retrenching in the renewable industry, if Trump and his congressional allies kill federal support:

The tax credit was expected to support 25 gigawatts of additional solar installations — a 54 percent increase that amounted to $40 billion in new investment through 2020. By the time the ITC falls to 10 percent in 2020, GTM Research expects the industry to be adding 20 gigawatts of new capacity yearly. By comparison, 6 gigawatts of natural-gas power plant capacity were added in 2015.

Reversing those figures provides a rough estimate of what might happen to solar if the tax credit is cut. Installations could fall by roughly half.

As for electric vehicles, the tax credits will help determine if new models like the 238-mile range Chevy Bolt, to be released next year, will sell for $37K or $29K — a very big difference for most consumers. But at some point they are scheduled to be phased out anyway, so it could just be a short-term setback to the industry, particularly with California’s strong policies on zero-emission vehicles.

And of course, we don’t really know what Trump and congress will do. We know many Republicans favor renewables, but we also know that a revision of the tax code in general could be in the works. And the last time that happened in 1986, renewable tax credits disappeared. They’ll need to save money somewhere to pay for their tax cuts for upper-income earners.

So it will be a wait-and-see situation, but it’s cause for states like California to start thinking immediately about backup support at the state level, such as through fees on polluters to cover clean tech support. As on many issues related to this election, it’s time to gear for the worst.

I’ve spoken to many people who are having trouble focusing after last week’s election. A Trump victory, with a multi-month transition process before he actually takes office, provides plenty of mental fodder for imagining disaster scenarios. Certainly on environmental issues, with a compliant congress, there’s virtually no limit to what he can do to unravel environmental protections.

But fear not — all that mind-wandering may actually be good for you, as a recent UC Berkeley/University of British Columbia study found:

“Everyone’s mind has a natural ebb and flow of thought, but our framework reconceptualizes disorders like ADHD, depression and anxiety as extensions of that normal variation in thinking,” said [study co-author and postdoctoral scholar Zachary] Irving. “This framework suggests, in a sense, that we all have someone with anxiety and ADHD in our minds. The anxious mind helps us focus on what’s personally important; the ADHD mind allows us to think freely and creatively.”

In the months and years to come, we will likely need that creative thinking as we figure out how to protect the environment and stabilize planetary temperatures in the face of this new political order.

This might sound crazy, but Donald Trump’s presidency could actually have a temporarily positive impact on climate change. How? Nothing reduces emissions like a recession, and according to economists, Trump’s stated policies are likely to cause one.

Specifically, if Trump follows through on his promise to start a trade war with countries like China, he could end up reducing the U.S. carbon footprint significantly. Imagine higher tariffs on goods from China, U.S. cars manufactured in Mexico, and stuff from the myriad other places that export items we buy. The result will be higher prices on those goods, which will mean less consumption. Less consumption means fewer carbon emissions.

Then think of the result on those producing countries. We could see a slowdown in the economy of places like China, where growth is in large part due to sales of cheap stuff to the U.S. market. Because China itself is now a major emitter of greenhouse gases, a slowdown there will also reduce global emissions.

This isn’t just theoretical: we have experience on this issue from the Great Recession. That slowdown caused a dip in the nation’s carbon footprint, according to a UC Irvine study. The recession also made it easier for California to meet its 2020 emissions goals, as E&E News reported:

“California had a pretty soft economy for many years after its goal was set,” said Severin Borenstein, an economics professor at UC Berkeley and a member of a committee that the California Air Resources Board (ARB) set up in 2012-13 to advise it on the design of its cap-and-trade market. “Although it’s heating up now, we will easily make the 2020 goal, and that will in large part be due to the weak economy for many years.”

Now to be clear, an economic downturn is not something to root for, and it would cause all sorts of hardship and potentially more political instability. To avoid that outcome, California regulators have been meticulous and careful about making the transition to a clean economy without shocking the economy. Indeed, the state is instead focused on ways to benefit economically from clean technology, contrary to the usual conservative complaints about environmental action costing jobs and economic growth.

But Trump’s policies on trade, immigration and other economic issues may lead us to a recession regardless of what California does. And if that happens, the one silver lining for those concerned about climate change is that it will likely offer a temporary pause to the emission of heat-trapping gases. And that could buy the world more time to emerge from a post-Trump era with still a fighting chance to limit climate change.

After last night’s presidential election results, it’s easy to despair that we’ve lost the fight against climate change. Trump will likely kill the federal Clean Power Plan and pull the U.S. out of the Paris agreement. He’ll also probably pull back regulations that make it harder to permit coal-fired power plants and conduct other business activity that furthers a fossil fuel-powered economy.

Yes, California’s climate program will continue, as a bright spot. But the state relies on the federal government in crucial ways to lessen the economic burdens to Californians of the transition to a clean economy. The immediate examples that come to mind are the federal tax credits and research on solar and wind energy, tax credits for electric vehicles and associated charging infrastructure, and general support for and research on energy storage technologies. Without that support, California’s climate policies will likely become more expensive and potentially politically unpopular.

So where do climate advocates go from here? My colleague Dan Farber’s post on Legal Planet is right on: use political leverage, the courts, and continued state action. But I fear the first two options will be made more difficult given the potential for a coming breakdown in our governance system, as the full weight of “11/8” is felt in our institutions, from the courts to congress to the media.

That leaves state action. And in this respect, as Dan described, there may be cause for hope. In fact, given the hostile national politics during even the Obama years with a Democratic congress, this election may be an important wake-up call about the most viable path forward, politically speaking — even had Clinton won. Especially since the federal Clean Power Plan, which represents the high-water mark for federal action given congressional resistance, has pretty weak targets that won’t set in for years.

California is the obvious state leader here, but so are other west coast and northeast states. We’re long past the time when those states should join together for unified policies to boost clean technologies and price carbon. Those coalitions are happening fitfully but need to be accelerated. That means unified carbon markets, incentives for renewables, and a common market for electric vehicles, among other policies.

Internationally, the Paris agreement was always just a paper commitment. Action to achieve the ambitious international targets will still require courageous policies at the state and subregional level. And now that the Paris agreement is called into question under a Trump administration, we can see the wisdom of California’s approach to sign up subnational entities to commit to this fight. The “Under 2 Coalition,” as it’s now called, represents 136 cities and states with 832 million people and $22 trillion in GDP. It’s the brainchild of Governor Jerry Brown’s senior advisor Ken Alex, and it may represent the world’s best hope to achieve the goals spelled out in the Paris accord.

So while many climate advocates will be playing defense at the federal level for the foreseeable future, the offensive play, to my mind, is through state coalitions and bolstering of the Under 2 Coalition. It’s not going to be easy, but it was always an uphill battle anyway. And while the climb is now steeper, we still have a way forward.

California’s housing affordability crisis gets worse by the day. The lower and middle classes are squeezed, due to decades of under-building as a result of restrictive local zoning and permitting. Since at least the 1970s, local communities up-and-down the state have simultaneously decided they don’t want newcomers to live anywhere near them.

Now two new studies are out to chronicle the problem and offer solutions.

The first up is from McKinsey & Company, in a study called “A Tool Kit to Close California’s Hoursing Gap: 3.5 million Homes By 2025.” They describe the problem in a few snapshots:

In Anaheim, Long Beach, and Los Angeles, households earning up to 115 percent of area median income, or $69,800 per year, are unable to afford local housing costs. In the city of San Francisco, a household earning $140,000 per year, or 179 percent of area median income, is squeezed.

They then went about figuring where new homes could go, with an eye toward more low-carbon infill homes:

We identified physical capacity to add more than five million units in “housing hot spots.” This is more than enough to close the state’s housing gap. More than a quarter million of these units could be built on urban land that is already zoned for multifamily development and is sitting vacant. Up to 3 million units could be built within a half-mile of high-frequency public-transit stations. More than 600,000 could be added by homeowners to existing single-family homes.

But of course identifying sites is not the same as getting the homes built. To that end, the study authors recommend a bunch of solutions, such as more funding for affordable housing and cheaper construction through modular units. But here are the main ones:

To unlock these units, California needs both public and private sector innovations. Shortening the land use approval process in California could reduce the cost of housing by more than $12 billion through 2025 and accelerate project approval times by four months on average. Reducing construction permitting times could cut another $1.6 billion, and raising construction productivity and deploying modular construction techniques up to another $100 billion. Governments could reallocate $10 billion a year in developer impact fees to other forms of revenue generation in order to lower housing costs. California could also incentivize local governments to approve already-planned-for housing to achieve 40,000 more units annually.

This study is helpful in shedding light on just how many units we need and where they could go to minimize environmental impact. But notably, the study lacks a financial feasibility analysis, and the solutions are, per usual, much easier said than done. Still, it’s a great addition to the housing conversation in California.

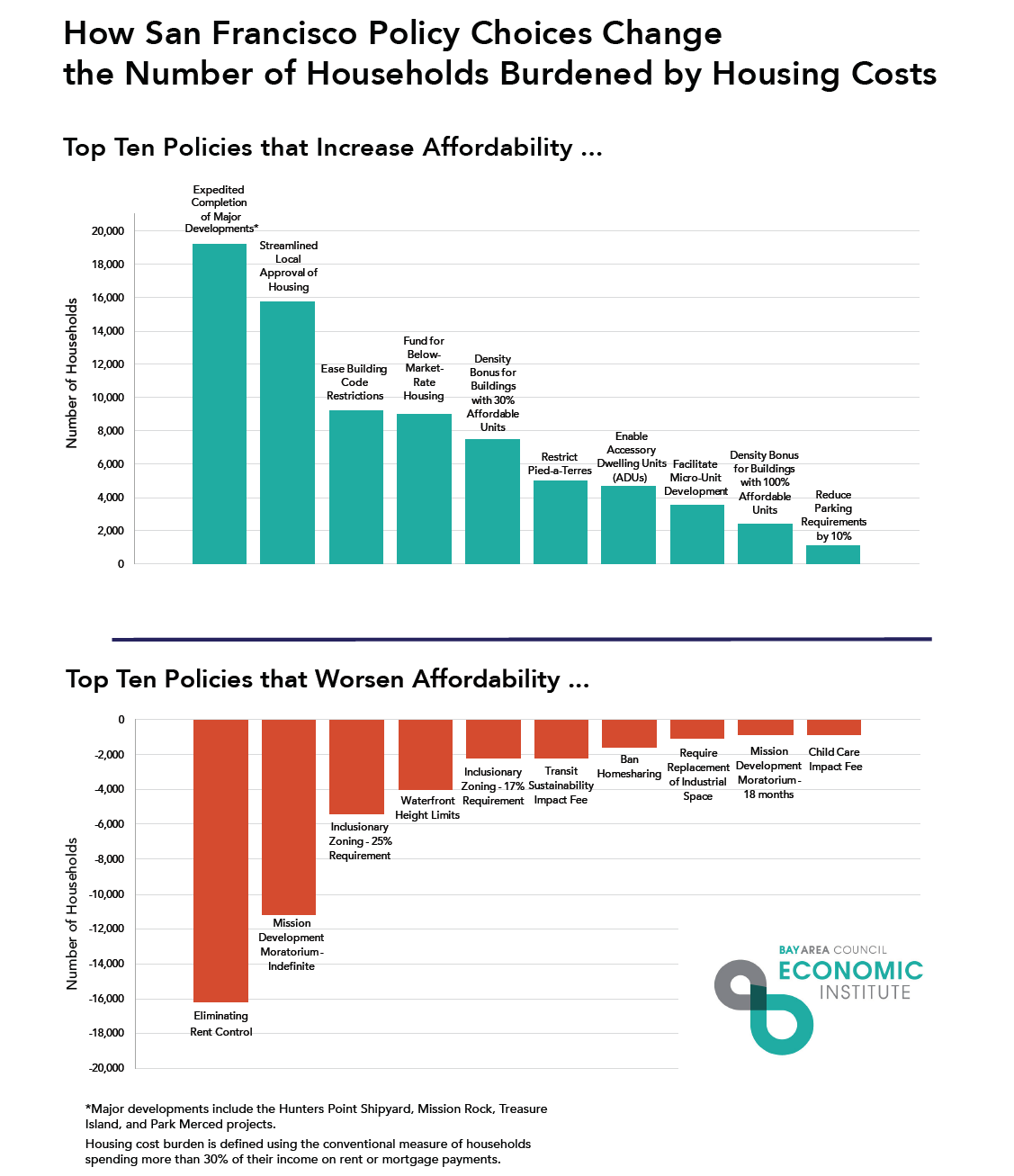

Meanwhile, the Bay Area Council conducted a similar study, “Solving the Housing Affordability Crisis: How Policies Change the Number of San Francisco Households Burdened by Housing Costs.”

Their bottom line? As with McKinsey, policy makers need to streamline and shorten the housing permitting process. Here’s the handy chart on high-impact local policies (for better and for worse):

Both studies should lend support for speeding up local approval processes, such as the governor’s failed “by-right” approval process for any project consistent with local zoning. Expect local representatives and their homeowners to put up a big fight. But if we continue to defer to them, the problem will only get worse, putting our economy and environment in continued jeopardy.

Both studies should lend support for speeding up local approval processes, such as the governor’s failed “by-right” approval process for any project consistent with local zoning. Expect local representatives and their homeowners to put up a big fight. But if we continue to defer to them, the problem will only get worse, putting our economy and environment in continued jeopardy.

To meet the challenge of climate change, California and other governments will need to adopt a suite of policies affecting multiple sectors. Reducing economy-wide greenhouse gas emissions will take reforms in energy, land use, transportation, and agriculture, to name just a few.

Since 2009, UC Berkeley and UCLA Schools of Law, with the generous support of Bank of America, have been developing policy recommendations for California and other jurisdictions to meet ambitious greenhouse gas reduction targets. In California and increasingly in other jurisdictions, these targets are legally mandated and based on what climate scientists tell us is needed to reduce the threat of catastrophic climate change.

Please join us for a free webinar on Wednesday, November 9th, from 2-3pm, to launch the two law schools’ new climate policy website. The site contains all the recommendations from our work since 2009 on reducing carbon emissions in multiple sectors of the economy. It features easy-to-navigate pages organized by issue topic (renewables, fuels, etc.). It also groups solutions around the specific challenges they address and lists them by the actors who can implement them (state officials, local representatives, businesses, etc.)

All of the policy recommendations result from a series of workshops the law schools have convened since 2009. They included key stakeholders from the business, academic, and policy sectors of the affected industries. The recommendations are also contained in reports accessible via CLEE or the UCLA Emmett Institute.

The webinar will feature:

- Mary Nichols, chair of the California Air Resources Board

- Nancy Pfund, founder and managing partner, DBL Investors

- Amanda Eaken, transportation & climate director, Natural Resources Defense Council

We will also include a demonstration of the website, now available at www.climatepolicysolutions.org

Register today at this link and to receive instructions about how to participate. Note that attendance will be capped. Hope you can join!