California’s cap-and-trade program likely can’t survive in its current form after 2020 without a two-thirds vote of the legislature to reauthorize it. That’s because a central feature of the program involves auctioning allowances to pollute, which courts are likely to consider to be a “fee” that requires two-thirds approval of the legislature under 2010’s voter-approved Prop 26.

With that high hurdle, advocates have been scrambling to get the needed votes. Despite having a Democratic super-majority in both houses of the legislature, a number of key Democrats are opposed to (or at least skeptical of) cap and trade, because they fear the program allows polluters to continue polluting disproportionately in “environmental justice” communities — predominantly low-income communities of color.

So advocates have had to seek a bipartisan two-thirds solution, which requires oil-and-gas industry support. And that means major concessions to the fossil fuel industry.

But at the same time, the fossil fuel industry has lost leverage. The passage last year of SB 32, to extend the greenhouse gas reduction goals from 2020 to 2030, and AB 197, which allows for direct command-and-control regulation of polluting facilities, has put their back against the proverbial wall. And they recently lost their lawsuit challenging the legitimacy of the current auction mechanism. Industry would rather have the more “flexible” cap-and-trade system now, where they can seek reductions in the most economically efficient manner.

So there are some industry concessions and some environmental wins in the apparent consensus bills unveiled on Monday. First, AB 398 would officially extend the cap-and-trade program to 2030. In a big win for industry, the legislation would prevent local air districts in California from imposing their own limits on greenhouse gas emissions from sources already covered under cap and trade. As the San Francisco Chronicle describes, it would “effectively kill long-running efforts by Bay Area air quality regulators to place hard limits on emissions of carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping gases from local oil refineries.”

In another win for industry, the bill puts a ceiling on the price of allowances (permits to emit one metric ton of greenhouse gases under the cap). To date, allowance prices have typically hovered at or near the current price floor. Consider the ceiling a gift to industry by giving them a maximum penalty they’d have to face for polluting.

But in a concession from industry, the bill would reduce the use of “offsets” (projects outside of the capped facilities that help reduce greenhouse gases) and require that half of them occur in California or have a direct environmental impact on the state. The use of offsets weaken the sale of allowances by giving industry a cheaper out, so this is good news for the integrity of allowances.

Finally, the bill would prioritize the kind of state programs that could receive funding from the auction proceeds. The money must first go to efforts to control toxic air pollution from mobile or stationary sources like factories and refineries, second to low-carbon transportation projects, and third to sustainable agriculture programs.

This last provision is potentially a mixed bag on impacts, since it doesn’t necessarily track the highest emitting sources. But it may allow continued funding for high speed rail, which is on financial life support and at this point is only propped up by cap-and-trade proceeds. The governor doesn’t want to see the project die, which was part of his motivation for getting the auction reauthorized.

Meanwhile, AB 167 is a must-pass companion bill would require stricter air pollution monitoring around industrial facilities and tougher penalties for violating pollution regulations. This measure allows environmental justice advocates to claim some victory be securing the promise of direct emissions reductions from nearby polluters.

A number of environmental groups are not happy with the concessions, although the bill has received support from the likes of Environmental Defense Fund and tepidly from billionaire environmental activist Tom Steyer.

For my part, I think it’s an okay but not great deal. It’s probably worth continuing the state’s cap-and-trade program, if nothing else to try to prove the concept in case it can be workable in other states and nationally. And the auction proceeds provide some useful funding for everything from weatherization to transit to low-income housing.

Meanwhile, the state still retains a lot of authority over polluters via SB 32 and the state implementation of the Clean Air Act, and multiple complementary policies are still needed and remain in effect to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, such as the renewable energy, energy storage, energy efficiency, and electric vehicle mandates.

The vote could come as soon as Thursday, so stay tuned for the results.

UPDATE: The vote was just postponed to Monday, which could mean they’re having trouble getting the needed votes.

Electric vehicles (EVs) represent one of the most promising clean technologies, in terms of their potential benefits for the electricity grid, local air pollution, and reducing the greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change. Not to mention they’re fun to drive.

Electric vehicles (EVs) represent one of the most promising clean technologies, in terms of their potential benefits for the electricity grid, local air pollution, and reducing the greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change. Not to mention they’re fun to drive.

The good news is that as EV prices have dropped by nearly half the last few years, the number of Californians driving them has gone way up, with almost 300,000 EVs now on the state’s roads (up from about 10,000 just five years ago). The batteries in these vehicles can be used to soak up surplus renewable energy, and the use of electricity instead of petroleum as a fuel means significant reductions in air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions.

But all this progress is threatened by the lack of reliable and accessible charging stations, particularly for the 40 percent of Californians who live in apartments, townhouses, and condominiums without dedicated on-site parking spaces with charging capability (including even just a simple wall outlet).

Researchers estimate that California may need up to 220,000 publicly accessible charging ports by 2020 to meet projected demand, way beyond the roughly 12,000 available today. Hundreds of thousands of additional charging stations may be necessary at those multi-unit dwellings.

Private investment alone won’t be enough to make it happen: the business model for charging stations is currently not strong enough to attract sufficient private capital. Simply put, many charging stations are too expensive to build and operate right now, without dependable near-term revenue to cover costs and produce a profit.

“Plugging Away” Report Releasing Today

To address the challenge, UC Berkeley and UCLA Law convened experts from the EV charging sector in 2016, including automakers, utilities, and charging companies, as well as government officials, academics, and nonprofit advocates.

To address the challenge, UC Berkeley and UCLA Law convened experts from the EV charging sector in 2016, including automakers, utilities, and charging companies, as well as government officials, academics, and nonprofit advocates.

Based on those discussions, the law schools are today releasing the new report “Plugging Away: How to Boost Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure.” It is the eighteenth report from our Climate Change and Business Initiative, generously supported by Bank of America since 2009.

Among a number of detailed solutions, the report recommends:

- More robust and strategic electric utility investments in charging infrastructure, at least for any new wiring to the charging station, in key locations such as workplaces, multi-unit dwellings, and fast-charge “plazas” to stimulate maximum EV convenience and adoption;

- Revised commercial electricity rates to encourage charging at the right places and times to best meet grid needs, including options to reduce high demand charges related to peak usage at remote fast-charging sites; and

- Targeted rebates and grants for office and multi-unit dwelling building owners to install charging stations, as well as expedited permitting to allow more curbside charging.

Free Lunch Event & Webcast at UCLA Law, Noon to 1:30pm

To launch the report, UCLA Law is hosting a free lunch event from noon to 1:30pm today, featuring a keynote by California Energy Commissioner Janea Scott and a panel including:

- Tyson Eckerle, Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development (GO-Biz)

- Terry O’Day, EVgo

- Dean Taylor, Southern California Edison

For those not in the Los Angeles area or unable to attend in person, the event will be webcast live.

I hope you can tune in or join. With a more robust and reliable charging network, policy makers and businesses can help ‘pave the way’ to more electric vehicle adoption in California and beyond.

The California Chamber of Commerce has just lost its case against the state’s cap-and-trade auction, with the news from the Los Angeles Times that the California Supreme Court has refused to hear an appeal from the state appellate court. This means the auction mechanism in the cap-and-trade program is valid at least through 2020.

As we’ve covered on this blog before (most recently with Ann’s post from last fall, which links to our other posts), industry plaintiffs had argued that the auction represented a tax that required two-thirds approval of the legislature, under Proposition 13. But the auction isn’t like a tax, the courts have now consistently and definitively ruled, allowing the current mechanism to continue through 2020.

After 2020, the auction may be subject to a different legal analysis under 2010’s voter-approved Proposition 26, which legally converted many “fees” to taxes and therefore extended the reach of the two-thirds bar. AB 32, the law that authorized the cap-and-trade program, passed in 2006 and therefore wasn’t subject to Proposition 26, which came later. Since AB 32 authorized the program specifically through 2020, it can now continue at least through that year without needing two-thirds vote in the legislature or facing further court challenges.

This is a significant win for the state for two reasons: first, it allows the auction to continue, which is a crucial feature for distributing allowances to pollute under the cap. It holds businesses economically accountable for on-site emissions reductions, rather than allowing them to get allowances for free (although there may be other, more convoluted ways that they could purchase auctions and avoid court challenges). Perhaps more importantly from a political perspective, the auction generates proceeds for the state that have been used to fund everything from high speed rail to transit and weatherization for low-income households.

Second, it means industry loses a bit of leverage to shape cap-and-trade going forward in the legislature, which is debating proposals to extend the program now. The case has loomed in the background on these debates, with industry potentially wielding it as a negotiation piece to extract concessions, implicitly if not explicitly. Coming on the heels of the passage of SB 32 and AB 197 last year, which directed more command-and-control type approaches to emissions reductions at regulated facilities, it represents another loss of leverage for industry going forward.

Meanwhile, cap-and-trade post-2020 debates are heating up at the Capitol, with the governor determined to extend the system before the August auction and solidify the program’s place through 2030, in part to ensure a continued revenue stream for high speed rail. Industry is now on board as well (although they’re trying to weaken the program as much as they can), as they’ve lost their fall back option of killing the auction completely in court and simultaneously face much more draconian command-and-control regulation if cap and trade doesn’t continue.

It makes me wonder what might have happened had the Obama Administration chose to use the Clean Air Act more aggressively back in 2009, which (if successful in court) would have made cap-and-trade at the federal level similarly more appealing for industry.

We’ll never know. But in the meantime, we can watch the political dynamic play out at the state level here in California, with one less card for industry to play at the negotiating table, courtesy of the state Supreme Court.

Few clean technologies are as central for meeting climate change goals as electric vehicles. Yet in places like California, which leads the U.S. with approximately 300,000 EVs on the road, the needed charging infrastructure is lagging.

Few clean technologies are as central for meeting climate change goals as electric vehicles. Yet in places like California, which leads the U.S. with approximately 300,000 EVs on the road, the needed charging infrastructure is lagging.

Analysts estimate that the state will need as many as 220,000 publicly accessible EV charging ports by 2020 to meet demand, well beyond the roughly 12,000 available in the state today. So how will California meet this challenge?

Join the UCLA and UC Berkeley Schools of Law for a free lunchtime forum on policy options to boost California’s EV charging infrastructure on Thursday, June 29th at UCLA Law. The two law schools will release a major joint report at the event as part of the Climate Change and Business Research Initiative, entitled “Plugging Away: How To Boost Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure.”

WHEN: Thursday, June 29th, 12 noon to 1:30 p.m. (registration and lunch begin promptly at 11:30am).

WHERE: Room 1447, UCLA School of Law, 385 Charles E Young Drive, Los Angeles, CA 90095

Keynote Address:

The Honorable Janea Scott, Commissioner, California Energy Commission

Panel presentations:

- Tyson Eckerle, Office of Governor Jerry Brown, Business and Economic Development (GO-Biz)

- Terry O’Day, EVgo

- Dean Taylor, Southern California Edison

RSVP by Friday, June 23rd. Space is limited, and MCLE credit is available.

Funding for the Climate Change and Business Research Initiative is generously provided by Bank of America.

Republicans tend to be skeptical of climate science and actions to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions out of concern for the negative economic impacts and the potential for more government regulation.

Republicans tend to be skeptical of climate science and actions to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions out of concern for the negative economic impacts and the potential for more government regulation.

But the reality is that fighting climate change represents a generational business opportunity for the United States. As I wrote recently, the required action will necessitate huge investments in everything from the electricity grid to the automobile sector.

Renewable energy in particular may be the “gateway drug” to get Republicans to support these investments. Take wind energy, as the New York Times reports:

The five states that get the largest percentage of their power from wind turbines — Iowa, Kansas, South Dakota, Oklahoma and North Dakota — all voted for Mr. Trump. So did Texas, which produces the most wind power in absolute terms. In fact, 69 percent of the wind power produced in the country comes from states that Mr. Trump carried in November.

So it’s not surprising that representatives and senators from these states have been some of the strongest supporters of federal tax credits for renewables in congress.

Overall, the electricity sector is one area where states have a lot of sovereignty to push for low-carbon technologies. Blue states in turn can encourage red-state action, which will help change the politics on clean technology in these states, as the clean tech industries mobilize and lobby their representatives.

A good example is the effort to integrate California’s grid with western states, as the New York Times story describes:

California and other Western states are discussing linking their electricity markets more closely, which would allow more renewable energy generated in the red states to flow to California consumers — and move California money into the pockets of red-state landowners.

Republican-led Wyoming, the nation’s largest coal-producing state, could be a prime beneficiary, with a proposed wind farm that would be one of the biggest in the world. The governors of Wyoming and California are discussing a deal, though both are nervous about giving up some control of their electricity markets.

That plan is held up by politics in California and a fear among these other states of having their grids controlled by California interests. But for climate advocates, it could be not only a long-term energy strategy, but a political one as well.

Jennifer Hernandez of the law firm Holland & Knight and John Gamboa of the Greenlining Institute criticized our recent UC Berkeley report on 2030 housing scenarios for California that could help meet the state’s long-term greenhouse gas goals.

Jennifer Hernandez of the law firm Holland & Knight and John Gamboa of the Greenlining Institute criticized our recent UC Berkeley report on 2030 housing scenarios for California that could help meet the state’s long-term greenhouse gas goals.

Their piece in the Fox & Hounds website makes the hard-to-argue-with point that California policy makers should design climate policies — and particularly cap-and-trade — with an eye toward the costs on average Californians.

From my perspective, the state is already moving in that direction, with detailed assessments of the impacts of these programs on everything from gas prices to electricity rates. The state is also mitigating the impact for residents, with “climate credits” on our electricity bills, a guaranteed set-aside of cap-and-trade auction revenue for disadvantaged communities, and greater electric vehicle rebates for low-income residents, among other efforts.

But sure, more could be done, and it’s smart to examine these policies critically. Certainly from a pure political perspective, California’s climate efforts won’t retain support if they cause price and other shocks to residents.

So I’m all with Hernandez and Gamboa on the general point, although I think they fail to acknowledge how much care and analysis the state has already put into the programs involved.

But then the article singles out “Right Type, Right Place” report for criticism for being obtuse on the impacts of climate-friendly housing on everyday Californians:

In one recent report, for example, some of the most respected housing policy thinkers in the state make the case that if California could only build more high-density housing in a narrow subset of urban areas along the coast—where transit is already in place—greenhouse gas emissions from cars could be reduced by nearly two million metric tons per year, household utility bills trimmed by $5 a month, and monthly transportation costs lowered by $58. All while requiring people to spend only $38 more per month on rent—and less than $14,000 more for an average home.

Where do we sign up, right? What the study, like so many others, fails to account for is the social cost—and the economic unlikelihood—of this “infill-only” scenario actually coming to pass. The authors’ housing cost data doesn’t factor in the cost, for example, of relocating hundreds of thousands of people already living in existing lower-cost, lower-density homes in these areas. The study doesn’t account for the fast-growing fees many coastal jurisdictions are imposing to slow this very type of housing (as much as $100,000 per unit in some places). Nor does it account for the stark differences in the cost of land, which is between three and 10 times higher in coastal areas than inland California (and which is the biggest reason so many workers slog through three-hour commutes each day).

Most importantly, the study seems to accept the fact that this “preferred,” coastal-focused housing scenario will produce an average monthly rent of $2,702. Even without factoring in massive displacement, rising local exactions, and land costs that are likely to push development elsewhere, this number alone should give everyone pause. To pay that much rent, an “average” household would need to earn $97,200 a year! The median income in California today is only $62,000.

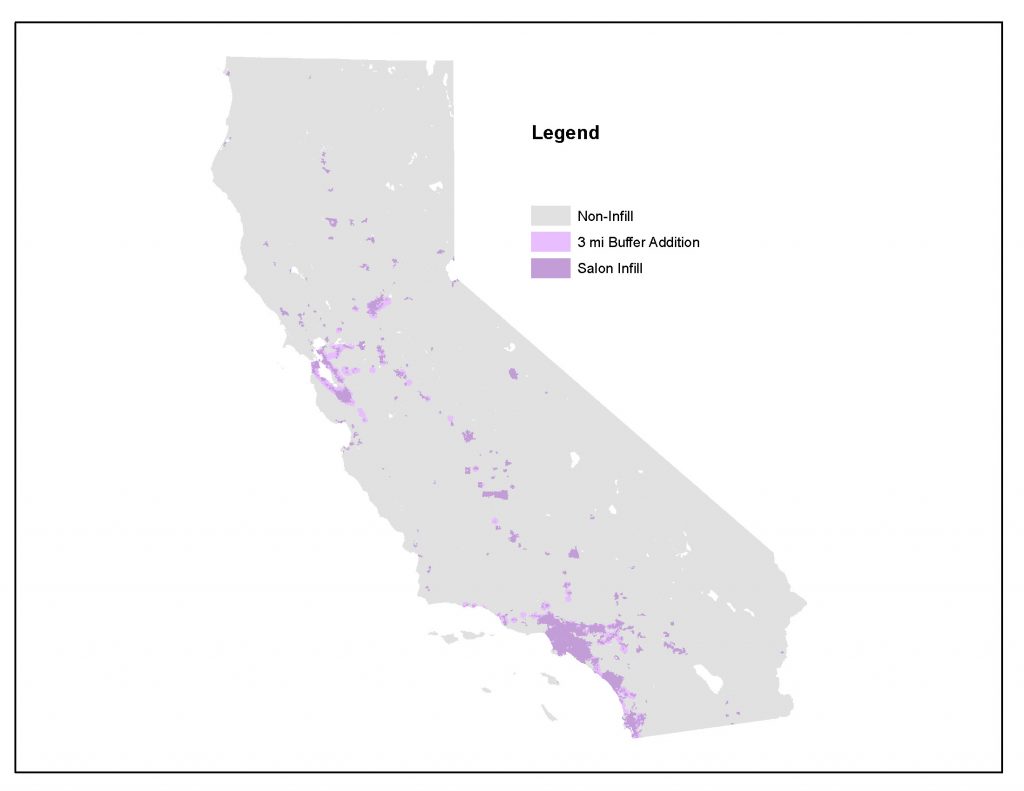

First, let’s look at the claim that our study limited development in the infill scenario to just a “narrow subset of urban areas along the coast.” One look at the map below of “purple” infill areas should dispel that characterization:

Sure, some of the purple areas are near the coast, but so is the vast majority of California’s population. This map shows that there’s actually a lot of land that could meet the preferred criteria all around the state.

Second, while it’s true our report methodology didn’t include a way to measure “social costs,” our policy recommendations addressed concerns around gentrification and displacement from infill development. And we offered ways to mitigate those impacts.

Third, the policy recommendations in the report also addressed the need to remove local barriers to housing in prime infill areas, such as the escalating fees on urban development that Hernandez and Gamboa mentioned.

Finally, Hernandez and Gamboa’s effort to compare the average rent in our infill scenario to median household income seems less important than comparing that rent amount to what Californians are actually paying today, when you combine average current household and transportation costs. That would be a more interesting comparison.

I should also note that if California actually succeeded in building enough housing to meet population growth, as our scenario assumed but as is not happening in reality, my personal view is that the extra housing supply would stabilize prices and rents in these infill areas (although we didn’t model that effect in our report).

As a general response to this criticism, our report did not do a financial feasibility analysis of the scenarios, so I think critiques related to that lack of information are valid. But we were up front about missing that level of analysis and recommend that future research build on this work. After all, this is the first comprehensive, academic effort to look at 2030 housing scenarios and how they can fit with the state’s greenhouse gas reduction goals. This report is an important starting point for this discussion, and we hope others build on it.

But it’s not accurate to suggest we didn’t think about these “social” and other economic costs. And this criticism also misses the added benefit of more infill housing for low-income residents which we also didn’t quantify: access to high-paying jobs in cheaper overall housing. Right now, with lower-cost housing out in sprawl areas, these residents not only face long commutes at high cost to access good jobs, they’re contributing to environmental degradation for everyone.

Solving that problem would be an environmental and economic win-win for all of California’s residents. And in any back-and-forth over details, we should not lose sight of that larger, more important point.

With so much noise coming out of Washington DC these days, from phony bill signing ceremonies to endless provocative tweets and misinformation, it’s easy to lose sight of the real, consequential policy battles going on at the moment.

On the environment, the big battle in Congress will take place over the budget late this summer. A temporary stopgap measure helped preserve funding for key environmental initiatives, such as clean energy research and transit projects like Caltrain electrification. But that bill just kicked the can down the road to September, when the government must act to avoid a shutdown.

The Trump administration’s proposed budget would zero out basically all environmental programs, including all new transit projects. I’m following the fate of clean energy research at the uber-successful ARPA-E in particular, at the Department of Energy:

September is now the new showdown date for the future of federally-funded breakthrough energy research in the United States. And if Trump has his say, the September fight could be waged in a higher-stakes, post-filibuster, 51-votes-to-pass-a-bill Senate. (Regardless, apparently, of any consequences for Republicans when Democrats next control the White House and/or Congress.)

On transit, the administration wants to end all federal support for urban transit projects, essentially ending a half-century of federal involvement in this area. As Transportation for America writes:

The administration reiterates their belief that transit is just a minor, local concern.

“Future investments in new transit projects would be funded by the localities that use and benefit from these localized projects,” they write, making it clear that they see no benefit in providing grants to cities of all sizes to build new bus rapid transit or rail lines, or expand existing, well-used lines so they can carry more passengers.

The administration even uses the example of local cities approving their own funding measures for transit as a reason to discontinue federal support, when those local measures were actually sold as ways to leverage federal dollars in this longstanding partnership.

The good news is that many of these programs and initiatives have bipartisan support. We saw that in action with the stopgap measure passed this spring. But that support will be put to the test as we witness an assault on federal dollars for the environment and public health like we’ve never seen before.

Trump’s announcement yesterday that the U.S. will withdraw from the Paris climate agreement (although technically not for another three years or so) was a big victory for his die-hard political supporters. A significant percentage of Republican voters simply discount climate science and hate the idea of global cooperation to address it.

Why do they feel that way? There’s been a fair amount of research on the question, but the bottom line is that they must feel like climate policies and programs will have no benefit for them — and may instead drive up their costs and undermine their employment opportunities.

At the same time, the U.S. economy has experienced an uneven recovery since the last recession, which has essentially only benefited the urban, knowledge-based parts of the country while almost completely leaving behind the rest with stagnant or declining wages. And that’s where these Trump voters made their stand and determined the election last year.

The irony though is that climate policies and related investments have a huge potential to benefit these rural areas and compensate for the tectonic economic changes that have left them behind. Just take California’s San Joaquin Valley, a poor and economically challenged part of the state. Our recent Berkeley Law report with Next 10 and UC Berkeley’s Labor Center showed that California’s three major climate programs — cap-and-trade, renewable energy, and energy efficiency — boosted the San Joaquin Valley’s economy by more than $13 billion and created thousands of new jobs to date.

The irony though is that climate policies and related investments have a huge potential to benefit these rural areas and compensate for the tectonic economic changes that have left them behind. Just take California’s San Joaquin Valley, a poor and economically challenged part of the state. Our recent Berkeley Law report with Next 10 and UC Berkeley’s Labor Center showed that California’s three major climate programs — cap-and-trade, renewable energy, and energy efficiency — boosted the San Joaquin Valley’s economy by more than $13 billion and created thousands of new jobs to date.

Or take high speed rail, which is a long-term effort to move people around the state on low-carbon electricity rather than petroleum-guzzling cars and airplanes. The Sacramento Bee editorial writers argued in support of the project precisely for its economic benefit to the San Joaquin Valley:

The $20 billion Central Valley to Silicon Valley leg won’t carry commuters until 2025, give or take. But once it does, the forgotten part of California that coastal residents fly over or zip past en route to Yosemite will become connected to the rest of the state and gain their share of California’s bounty. That’s not a boondoggle. That’s fair.

Nationally, a “deep decarbonization” strategy for the entire U.S., with its attendant investments in the electricity grid and vehicle electrification, could generate up to 2 million jobs by 2050, according to ICF International. Many of those jobs would happen in the economically challenged parts of the country that supported Trump and his decision yesterday.

So the solution to building more political support for climate change policies therefore rests within the solutions to combat climate change in the first place. But given recent events, that message is simply not coming across to the parts of the country that need to hear it.

If it’s true, as reported, that Trump will withdraw the United States from the international climate change accord negotiated in Paris in 2015, it will be a symbolic abdication of U.S. leadership on clean technology and climate. And if the U.S. does not get a more climate-friendly president in January 2021 (or sooner), or somehow get a change of heart from this current one, it could have serious environmental consequences for the planet.

If it’s true, as reported, that Trump will withdraw the United States from the international climate change accord negotiated in Paris in 2015, it will be a symbolic abdication of U.S. leadership on clean technology and climate. And if the U.S. does not get a more climate-friendly president in January 2021 (or sooner), or somehow get a change of heart from this current one, it could have serious environmental consequences for the planet.

It’s important to note that the agreement itself was essentially symbolic, although it provides an important structure for global cooperation on greenhouse gas emissions reduction and can be strengthened over time. The agreement isn’t binding, and the U.S. contributions to the global emissions reduction effort are predicated on domestic policies like the Clean Power Plan, which the Trump administration is now trying to roll back anyway.

As my UCLA Law colleague Ann Carlson notes, staying in the agreement would mean masking the administration’s full-scale attack on domestic climate change programs. So in some ways, the agreement itself is a distraction from the administration’s policies on everything from expanded oil-and-gas exploration on public lands, rollback of vehicle fuel economy standards, and efforts to undermine renewable energy and public transit, among others.

In terms of actual emissions reductions though, the Paris agreement — and the policies supporting it like the aforementioned Clean Power Plan — weren’t really meant to start immediate changes to our energy system. The real action for most of these efforts begins in the 2020s. So the good news is that substantively, there’s still some time to make progress on climate, even with a four-year (or less) pause in federal climate action.

But the bad news of course is that we lose these years of taking action, with no guarantee that the U.S. will change course politically anytime soon. And time is already running out to avert the worst impacts of climate change.

But one other silver lining to the administration’s anti-climate actions: it has motivated states like California and cities across the country to do more to reduce emissions, while also emboldening the European Union and China to step in and become economic leaders in the effort to transition to low-carbon technologies. While that’s a political loss for the U.S. as a whole, it points to the potential for much more decentralized, global action on climate.

The more I learn about hydrogen fuel cells as a potential alternative (or competitor) to battery electric vehicles, the more confused I become.

Hydrogen as a fuel source (as opposed to electricity) is much more energy intensive to produce and much less efficient as a result, given the energy input to make the hydrogen that will power the vehicle. It also requires building an entirely new fueling infrastructure to reach drivers, whereas electricity is ubiquitous (although does require a lot of new charging stations).

Hydrogen also isn’t cheap (per paywalled Greenwire):

Hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles could offer advantages over the electric cars on the road now, including higher travel distances between refuelings. Filling up the tank is basically the same as filling a car with gasoline, and in California, most hydrogen pumps are at existing gas stations. While the hydrogen fuel is significantly more expensive — filling a tank costs about $75 — Toyota and Honda give their customers credit for $15,000 worth of fuel over three years of ownership.

So why the big push for hydrogen in places like California, when battery electric vehicles have taken hold with billions of investment from companies around the world?

The answer appears to be Japan, and the automakers in that country, specifically Toyota and Honda. States like California have had to include hydrogen incentives in packages with battery electric vehicles in order to get the political buy-in from these Japanese automakers.

So with all the hurdles associated with hydrogen fuel cells, why is Japan so invested in the technology? Per ClimateWire (also pay-walled):

A big part of the answer is that the shift toward hydrogen plays to Japan’s strengths as a technology developer and exporter, and the country makes an ideal laboratory to test the hydrogen economy.

The country spends more than $100 billion on foreign oil every year, and fuel prices tend to be high, so hydrogen fuel doesn’t have to be as cheap as it does in other countries to compete. More than 93 percent of Japan’s population is concentrated in urban areas, so fewer fueling stations are needed to sustain a hydrogen fleet than among populations that are more spread out.

For drivers, a fuel cell fill-up takes only a few minutes, compared with hours of charging for a battery-electric vehicle.

Another factor is that much of the supply chain for the hydrogen economy is domestic, and Japanese companies like Toyota have a track record of bringing fuel-efficient cars to the masses.

In particular, Toyota has built the Prius, a mass-market hybrid gasoline-electric car that has dominated the segment for more than 20 years. It took 10 years to sell the first million units, then two years to sell the second million.

With patience and know-how, Toyota hopes to replicate some of that success in fuel cells in Japan and in other parts of the world where energy prices, environmental concerns and driving styles align to make fuel-cell-powered cars a preferable option.

I suppose it’s fine to have another “clean” vehicle technology in the mix, in case breakthroughs help it leapfrog battery electric vehicles. But I would prefer that policy makers don’t share too much of the limited available incentive dollars with this technology and instead focus on the more optimal solution.