In my excitement over SB 827, the new bill that would dramatically boost badly-needed new housing in job- and transit-rich areas in California, I overlooked one potentially important source of opposition: low-income renters near transit. As I described, the bill would limit local restrictions on height, density and parking near transit. I assumed that these changes would mostly affect relatively affluent single-family home neighborhoods near transit, whose residents and allied elected officials often prevent new housing for reasons ranging from the deplorable (racism) to the understandable (fear of more traffic and related hassles).

But for renters and their advocates in existing low-income neighborhoods near major transit stops, the SB 827 approach raises different fears: eviction through displacement and gentrification. They fear the relaxed local government rules under SB 827 will prompt developers to gobble up their existing low-income buildings, evict the tenants, tear down the structures, and then build market-rate housing for people with much higher-income levels. In short, they see SB 827 putting displacement and gentrification in these transit-rich, low-income communities on steroids.

The fear is legitimate, though I believe potentially overstated, depending on the neighborhood. And it’s also something that can be mitigated, with the right policy approach. First, it’s probably overstated because development in low-income communities is not necessarily held back only by strict local zoning. For example, as UCLA scholars Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris and Tridib Banerjee described in a report examining neighborhoods around the Blue Line light rail from Downtown Los Angeles to Long Beach, low-income areas near the station stops have received virtually no investment in real estate despite sometimes very relaxed local zoning.

The problem in many of these neighborhoods is that demand is not sufficient to attract developers and capital needed to build multistory buildings. These relatively expensive structures must net high rents to justify the higher construction costs. Compounding matters, many low-income neighborhoods often require significant infrastructure upgrades to accompany any new buildings. All of these factors deter developers from investing — not the local zoning codes. Ultimately, capital will flow to the areas that promise the highest return: which means relatively affluent neighborhoods near transit will see the most construction under the SB 827 approach.

Still, those economic dynamics probably won’t by themselves allay the fears of low-income renters and their advocates. Many of the neighborhoods they care about are at risk of gentrification, which means rents could increase, higher-income residents would move in with new construction, and low-income renters forced out.

So what can be done in these situations? There’s a rich literature on the subject, but one of the best ways to mitigate these impacts is to ensure a percentage of the new homes built are available exclusively to people with low incomes. Furthermore, local residents who have been displaced or are at risk of displacement should have priority access to these new homes.

The state already has policies on the books to encourage this type of affordable housing construction, from a now-stricter regional housing needs process (which requires locals to plan and zone for affordable housing in their jurisdiction) to density bonuses for projects that incorporate more affordable units. Local governments are also free to enact their own additional policies to boost affordable housing.

These and other policies may not help all tenants facing displacement, but they would go a long way toward helping many of them — and providing access to better homes for many of them in the process. And overall, new housing near transit will benefit residents of all income levels, including low-income. It will stabilize home prices to allow more residents to live near jobs and save on transportation costs from avoiding long commutes. It will improve public health by reducing regional driving miles. It will provide high-wage construction jobs. It will reduce economic inequality and lack of access to good jobs. And it will unlock the housing that future generations will need to be able to remain in their home communities.

Ultimately, we know we need new housing in California — and lots of it to make up for decades of shortfalls. We should have policies in place to ensure low-income renters gain from this construction. But if we don’t build these homes near our transit- and job-rich areas, then where are we going to build them? SB 827 provides the clearest solution to this decades-long problem in the making. But policy makers should take care to address the concerns of low-income renters who might otherwise stand to lose under this otherwise badly needed legislation.

With 2018 here, we can now say goodbye to the incandescent light bulb — at least in California and soon nationwide. The inefficient, polluting, and short-lived old bulb from Edison’s day is now required to give way to higher-efficiency LED and flourescent bulbs, per federal and state law.

With 2018 here, we can now say goodbye to the incandescent light bulb — at least in California and soon nationwide. The inefficient, polluting, and short-lived old bulb from Edison’s day is now required to give way to higher-efficiency LED and flourescent bulbs, per federal and state law.

As the Sacremento Bee reported last month:

Driving the change is energy efficiency. Former President George W. Bush signed a law in 2007 that gradually phases in new standards for bulbs, with the latest installment set to take effect across the country in January 2020. The federal law allows California to implement the regulations two years earlier, state officials say.

The new rules don’t explicitly ban incandescent bulbs. Instead, they impose such high energy standards that the incandescent bulbs will become effectively obsolete.

“Incandescents won’t be able to compete,” said spokeswoman Amber Pasricha Beck of the California Energy Commission. “When a consumer goes into a store they will not see an incandescent bulb.”

The change is a positive one, as it will save consumers money and the hassle of having to frequently change bulbs. And as more people buy LEDs, the prices have come way down while the selection has greatly improved.

Meanwhile, the environmental benefits are huge, given that lighting is about 7 percent of the country’s electricity usage. That means we will not need to build as many expensive, polluting power plants.

All in all, this change is a bright idea that will surely illuminate the benefits of cost-effective climate strategies for everyone.

With a rough 2017 on the environment now in the books, here are the top issues I plan to follow in 2018 on climate change:

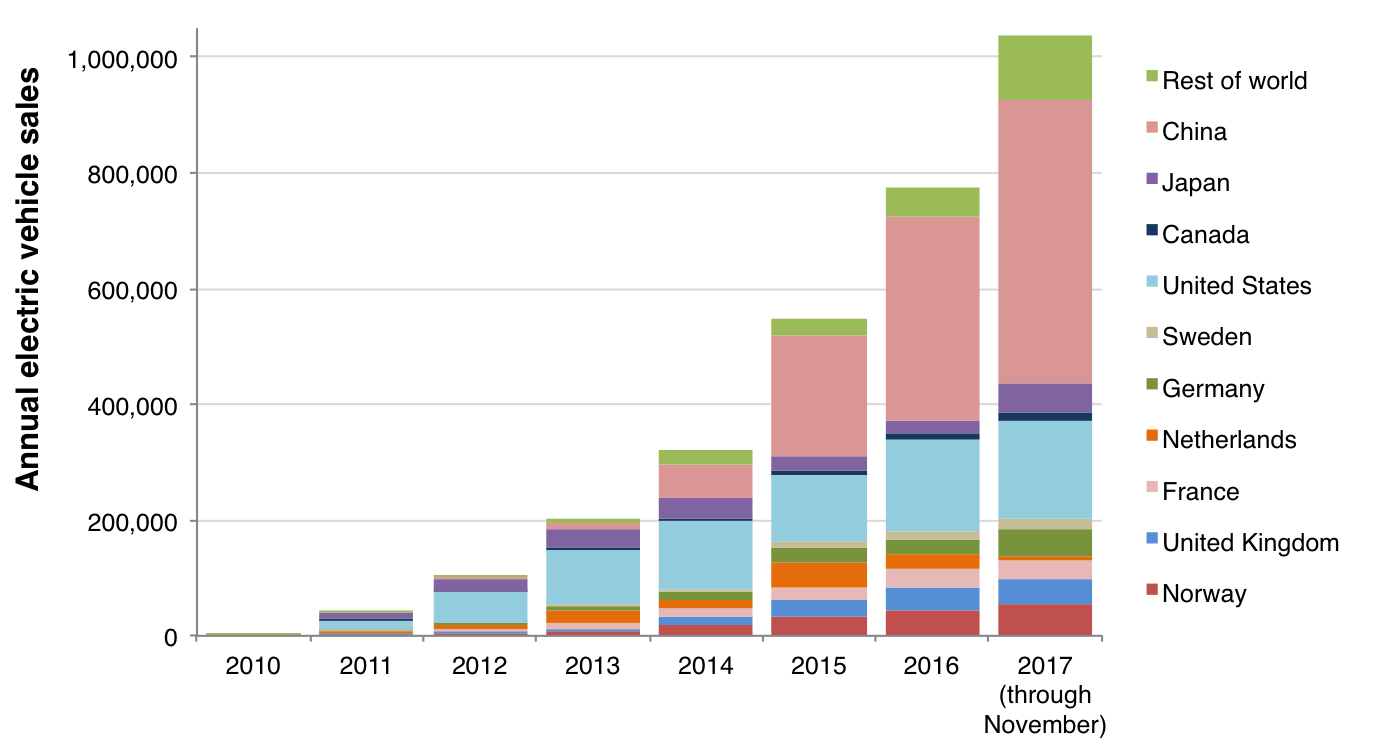

- A possible boost for electric vehicles from new models and global demand: With the more affordable Tesla Model 3 finally trickling out, plus aggressive EV policies in countries like China, hopefully we will see continued increases in demand for electric vehicles. Here’s an interesting chart on EV adoption worldwide, illustrating in particular the pivotal role that China is playing:

- Impacts of potential oil price increase: OPEC nations have already decided to cut oil production, which could mean that prices will increase with less supply (perhaps even despite more pumping from the U.S. and Russia). If oil prices rise, gas prices will go up, possibly leading to more demand for electric vehicles and other fuel-efficient vehicles and a decrease in pollution.

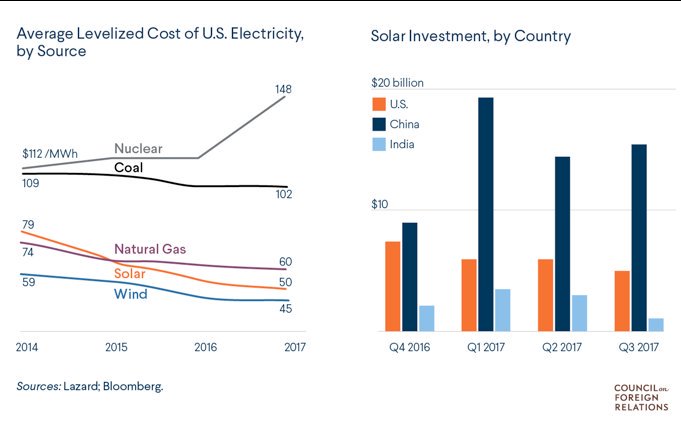

- Renewable energy’s political headwinds and tax uncertainty, coupled with falling costs: The Trump administration is doing everything it can to boost coal and undercut renewables (particularly with likely tariffs coming on foreign solar panels). And the 2017 federal tax legislation creates uncertainty for wind and solar tax credit financing going forward. But the economics of renewables continues to defy expectations. Here’s a chart with some more details on the rapid progress made in the past few years, including just in 2017:

- More extreme weather & environmental challenges: 2017 was a doozy on extreme weather, with another record-breaking temperature year that included brutal wildfires and hurricanes like we’ve never seen. As the climate continues to warm, expect more of these events, with the potential for them to change the politics around climate. Special mention: the impact of Puerto Rican refugees on Florida politics.

- U.S. state action to fill the federal void on climate leadership: States (and many cities) are continuing to move aggressively on climate. Will we see more states join California’s cap-and-trade program or implement strong greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets, including carbon taxes? Will we see multi-state collaborations on climate? This year could provide some opportunities for state gains on climate leadership, particularly in states like Oregon and Washington, plus the continued possibility a regional western-wide grid to facilitate renewable deployment across the western U.S.

- 2018 mid-term elections: A Democratic takeover of at least the House, if not the Senate, would dramatically change the prospects for climate policy in the country. A Democratic House means the purse strings could swing back in favor of funding environmental measures, plus some congressional oversight on agency action (or inaction or worse, in the case of climate change). A Democratic Senate could in turn mean much more moderate judicial nominees who hear cases on agency decision-making on the environment.

Honorable mention: California housing policy. While 2017 was supposed be the “Year of Housing,” much more work remains to be done. Will California legislators finally start to rein in local control over land use, which has prevented sufficient infill housing in thriving metropolises from getting built? And relatedly, will California voters overturn in November the state’s new gas tax increase, which helps fund transit and road repair to serve infill housing?

Lots of interesting issues to follow this year. Thanks for reading this blog — I look forward to covering them all and more in 2018.

This has been a tough year for the environment at the national level in the U.S. We’ve seen rollbacks of key protections, gutting of enforcement, efforts to open up resource extraction on public lands, and a general abdication of climate leadership at home and globally.

On the bright side, states and cities have stepped into the void, providing some good news. And nonprofits have had wins at the courts and at various other levels of government. Businesses, meanwhile, have also made progress, particularly on various clean technologies like battery electric vehicles and renewables. Business leaders have also become strong advocates for climate action globally.

And internationally, countries like China are now aggressively tackling carbon emissions, both with carbon markets and other efforts to control pollution, as well as by promoting clean technologies.

With the holidays here, I’ll be off blogging until the new year, which will hopefully bring some better results overall than we’ve seen in 2017 on the environment and other critical challenges facing the globe.

Wishing everyone the best until then. And in the meantime, enjoy Joni Mitchell’s reflective take on the holidays from 1971:

Climate change and the recent five-year drought in California have now rendered 129 million trees dead in the Sierra Nevada mountains. As a result, they are more susceptible to catastrophic wildfires like we’ve seen this fall in the state’s coastal areas. California’s Sierra Nevada Conservancy has an informative webpage and videos dedicated to educating the public about the urgent need to manage the forests better.

The first video describes the immediate need for action, particularly given the forests’ role as a carbon sink, which could turn to carbon emitter without better management:

The next video shows the risk of continued fire suppression and need for more controlled burns:

The final video shows what controlled burns can do to restore the forest ecosystem and provide carbon benefits:

But as UC Berkeley forest expert Van Butsic described in a recent interview with Water Deeply, the solutions will be controversial, most likely requiring “mechanical thinning” in forests that some environmental groups oppose. Yet as the videos above make clear, the price of continued inaction and fire suppression will only exacerbate the environmental catastrophe we are facing in these beautiful mountains.

A common knock on California’s climate programs is that they often end up disproportionately benefiting the wealthy. From cash rebates for Tesla drivers to lower electricity rates for single-family homeowners with solar panels, there was some truth to the complaint.

A common knock on California’s climate programs is that they often end up disproportionately benefiting the wealthy. From cash rebates for Tesla drivers to lower electricity rates for single-family homeowners with solar panels, there was some truth to the complaint.

But in the last few years, the legislature and other state leaders have made efforts to expand the benefits of these programs to low-income Californians. Rebates for electric vehicles, for example, are now means-tested and not available to high-income residents, and at least 25 percent of cap-and-trade auction proceeds must go to disadvantaged communities.

Now residential solar incentives are part of the mix, too. The California Public Utilities Commission just approved spending $1 billion in cap-and-trade dollars over the next 10 years on incentives for landlords to install rooftop solar panels on apartment buildings housing low-income residents. The San Jose Mercury News has more details.

Overall, the program seems like a smart investment, given that multifamily dwellers (especially of the low-income variety) are otherwise cut out of these opportunities if they don’t own their roofs. Politically it also gives more Californians a stake in the state’s climate programs, which helps build public support to keep the programs stable.

But it would be nice to see this program bundled with energy efficiency incentives. Just like solar is a tough nut to crack, given the split incentives among landlords who own the building and the tenants that pay the bills, so is energy efficiency work, which should be the first priority to save energy. Bundling efficiency incentives with solar could make landlords more open to doing this retrofit work, as well as making it more economically effective.

I’d also note that overall, California’s climate programs are benefiting the economy and creating jobs in some of our most disadvantaged regions, including the San Joaquin Valley and Inland Empire, as we studied in reports this year. And as wealthier residents purchased clean technologies like electric vehicles and solar panels when they were expensive in the early years of production, they’ve helped bring the costs down to the point where these technologies are now affordable to many millions of Californians.

But overall this solar incentive program is a good step in the right direction, and a harbinger of more climate programs to come that will benefit the state’s low-income residents.

Last month, while many environmental leaders went to Bonn, Germany for the U.N. climate talks, I journeyed to the Caribbean island of Aruba for the Green Aruba 2017 energy conference to speak on an environmental panel.

Last month, while many environmental leaders went to Bonn, Germany for the U.N. climate talks, I journeyed to the Caribbean island of Aruba for the Green Aruba 2017 energy conference to speak on an environmental panel.

Before going, the only thing I knew about Aruba was that it was the first lyric in the 1988 Beach Boys hit Kokomo. But it turns out Aruba is a leading island on clean energy in the Caribbean. And that’s a big deal.

As the Clean Energy Finance forum detailed, small islands are often perfectly positioned to benefit from a transition to clean energy:

- First, they typically pay a lot of money for dirty electricity, as they usually rely on imported oil to burn to generate power. This leaves them vulnerable to price shocks.

- Second, they often have abundant renewable resources from sunshine, wind, wave and sometimes geothermal and biomass.

- Third, they need to be more resilient in the face of extreme weather anyway, so relying on locally generated power for a decentralized grid is an important resilience strategy (a need that’s become clear with Puerto Rico’s continued blackout in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria). Moody’s even recently rated some of these islands as risky for investors due to their exposure to climate events, per Bloomberg.

Aruba is one of the best positioned to go green. The island is relatively wealthy, as it pivoted from an economy heavily dependent on oil refining in the 1980s to one big on tourism. Many Americans from the East Coast spend a lot of money there, given the picturesque beaches, pleasant weather (very little rain and almost no hurricanes), and the ability to use dollars and get by with English on the island (it’s a former Dutch colony with a local Papamiento language, but everyone learns English).

The island’s political leaders committed in 2012 to a 100% clean energy goal by 2020. As a result, the utility has been a leader in investing in renewables, with plans for more. The island residents and visitors use about 100 megawatts of electricity, and a wind farm on the windy north coast, which is mostly in the national park, generates 30 megawatts of power. They also built a 4 megwatt solar park at the airport. Together with some other resources, the island can credibly generate 40% of their power from renewable sources, depending on the sun and wind. Plans going forward include another wind farm, Tesla batteries, more solar, and a waste-to-energy facility.

But notably, these projects have faced some community opposition that might be familiar to clean energy advocates elsewhere. The new wind farm, for example, is proposed in a major bird area, as local bird expert and activist Greg Peterson told me. With land in limited supply, and increasing development pressure from a growing population and economy, birds and other wildlife are suffering on the island. So island leaders will need to find a way to develop clean resources in a way that preserves Aruba’s wildlife and natural beauty.

But despite these conflicts and pressures, Aruba is a pioneer on green energy and a leader for other island nations to follow. And if the island is successful in achieving its 100% clean energy goal, it will be a leader for larger countries like the U.S. as well.

Meanwhile, to get a taste of the conference, here is a video of a workshop for youth held the day before the formal conference began. As you can see, Aruba is worth visiting for more than just the beaches and weather, given its green energy policies.

When President Trump announced in June that the United States would be withdrawing from the Paris climate agreement, France eagerly stepped into the leadership void. French President Macron responded by offering millions in new grant money for climate science research.

The winners were just announced, including 13 American scientists out of the 18 winners. I spoke to KCBS radio in San Francisco yesterday about the program and what it means for the United States going forward. You can listen to the 4 minute clip here:

Audio PlayerUPDATE: Initial reports that the electric vehicle tax credit was killed in the Senate version may have been inaccurate. The text of the amendment contained some obscure language that actually indicates that it was not adopted in the ultimate bill.

Donald Trump’s electoral college win a year ago certainly promised a lot of setbacks to the environmental movement. His administration’s attempts to roll back environmental protections, under-staffing of key agencies enforcing our environmental laws, as well as efforts to prop up dirty energy industries have all taken their toll this year.

However, until the tax bill passed the Senate this week, much of that damage was either relatively limited in scope or thwarted by the courts. But the new tax legislation now passed by both houses of Congress, and still in need of reconciliation and a further vote, could dramatically undercut a number of key environmental measures in ways we haven’t yet seen from this administration.

Originally, there was some hope that Republicans in the U.S. Senate would weaken some of the draconian environmental measures in the original House tax bill. But that was largely dashed by the late Friday night, partisan vote in the U.S. Senate. First, the bill targets clean technology while promoting dirty energy:

- The renewable energy tax credits for wind and solar are severely undercut by an obscure provision in the bill called Base Erosion and Anti-abuse Tax (BEAT), as Greentech Media reports. While analysts are still reviewing the provisions to discern the likely impact, initial assessments are that this bill language could greatly hurt the industry by decreasing the value of the credits.

- Similarly, the reinstatement of the alternative minimum tax for corporations, which was not in the House bill, also hurts the market for renewable tax credits, if not devastates it. By inserting this provision at the very last minute, Senate leaders attempted to offset some of the other tax cuts and projected deficits by ensuring corporations pay a minimum tax. The problem is that it renders many tax credits worthless, as businesses will no longer need them. Particularly hurt are wind energy projects, which rely on the production tax credit, as well as solar projects that rely on the investment tax credit.

- As a dirty cherry on top, the Senate bill opens the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil drilling.

On housing, the tax bill has the potential to devastate affordable housing. Affordable projects often rely on tax credits for financing. As Novogradac & Company writes, the BEAT provision will dampen corporate investors from claiming tax credits like the low-income housing tax credit (LIHTC), new markets tax credit (NMTC), and historic tax credit (HTC), all used to fund affordable and other infill projects. Other changes in the bill promise further dampening of financing for affordable housing.

The only good news for environmental and housing advocates is that there is still a chance to make changes in the bill through the conference committee. And that the provisions here can be rescinded in 2021 with a new congress and president.

California has an aggressive goal to double the energy efficiency of existing buildings by 2030. The problem though is that building owners don’t seem very interested in having energy retrofit work done on their house or commercial property. We covered this subject in a recent Berkeley/UCLA Law report Powering the Savings, as well as in a September panel event at Berkeley Law.

California has an aggressive goal to double the energy efficiency of existing buildings by 2030. The problem though is that building owners don’t seem very interested in having energy retrofit work done on their house or commercial property. We covered this subject in a recent Berkeley/UCLA Law report Powering the Savings, as well as in a September panel event at Berkeley Law.

A reporter from E&E News attended that event and interviewed a few of us afterwards. Her article (paywalled) described some of the challenges:

The price tag for California’s goal is extremely high. Retrofitting all owner-occupied housing units in California — half of all housing — would cost $180 billion, DeVries estimated. There have been about $4.5 billion worth of retrofits under PACE programs nationwide, mostly in California. “I don’t think we’re going to find the money here,” he said. “We’re going to have to find it elsewhere, which means Wall Street, which means securitizations.”

Wall Street has the appetite, according to DeVries. His company’s latest offering of $220 million in project-backed bonds saw four times more demand than the available supply. The problem is consumer demand. “You can have all the investor interest in the world, and it doesn’t matter one bit,” he said. “The chicken and the egg here — the demand has to come first.”

Figuring out easy, capital market-type financing could help drive this demand, as we’ve seen with rooftop solar. And finding ways to reach building owners during key moments is also important, like when they’re between tenants or when remodeling or appliance replacements are in the works. But at some point, the state may need to move toward mandatory retrofit requirements during times of change in ownership or tenancy, as other jurisdictions have done.

Without these steps, what should be one of the most cost-effective ways to fight climate change may continue to under-perform and under-deliver.