The electric vehicle revolution appears to be passing renters by. And the solution involves deploying more charging stations.

In a new working paper and blog by UC Berkeley energy economist Lucas Davis, he finds that homeowners are much more likely than renters to own an EV, even with similar incomes. He found, for example, that among households with incomes between $75,000 and $100,000 per year, 1 in 130 homeowners owned an EV, while only 1 in 370 renters owned one.

Why the discrepancy? As Davis explains, it’s about access to charging:

Most homeowners have a garage, a driveway or both. That makes charging extremely convenient for them because they can charge their vehicles at night.

It’s not so easy, however, for many renters. Renters are more likely to live in multi-unit buildings and parking spots may not be assigned, or there may not be any parking spots at all. The federal data doesn’t provide any information about parking availability, but this likely helps explain the disparity between homeowners and renter EV ownership rates.

There is also the related question of charging equipment. For homeowners, it is relatively straightforward to invest in a 240-volt outlet, electric panel upgrades and other improvements to speed up charging. These investments can cost $1,000 or more, but are a good investment for a homeowner planning to stay put.

Making this investment is trickier for renters, however. They may not want to invest their own money in a property they don’t own and their landlords may be unwilling to let them do it in any case due to liability and other concerns.

The best solution is to deploy more EV charging stations at workplaces and in fast-charging “plazas,” as we described in our 2017 Berkeley / UCLA Law report Plugging Away.

The best solution is to deploy more EV charging stations at workplaces and in fast-charging “plazas,” as we described in our 2017 Berkeley / UCLA Law report Plugging Away.

And more charging stations are needed not just for apartment dwellers and renters but to meet our climate goals more generally. In a recent report by the Center for American Progress, the authors found that most states in the U.S. have funded less than half of the deployment needed to meet our Paris climate accord commitment.

As E&E News reported on the study [paywalled]:

The analysis found that some 330,000 new public Level 2 and direct-current fast-charging stations would need to go up around the country by 2025.

At a cost of $4.7 billion, those networks would feed power to the 14 million plug-in hybrids and battery electrics necessary to bring greenhouse gas emissions from light-duty cars in line with the accord.

It’s a lot of money that’s needed — but also potentially a lot of revenue from selling electricity as vehicle fuel. With more utility and potentially automaker investment, this infrastructure goal should be feasible to achieve, if we muster the political will.

Some environmentalists have noted with schadenfreude that the auto industry is getting its just desserts now for pressing the Trump administration to weaken Obama-era fuel economy standards. While the auto industry may have originally just wanted some additional flexibility for compliance, instead they got a wholesale revocation of the program.

And this rollback means a worst-case scenario for the auto industry, with potentially years of litigation and uncertainty to come. In short, they won’t know what type of vehicles to produce for the next few years at least.

So if the auto industry didn’t want the administration to take this approach, why is it happening? The answer may involve the other industry that benefits from weakening fuel economy standards: Big Oil. As Bloomberg reported:

The Trump administration’s plan to relax fuel-economy and vehicle pollution standards could be a boon to U.S. oil producers who’ve quietly lobbied for the measure.

The proposal, released Thursday, would translate into an additional 500,000 barrels of U.S. oil demand per day by the early 2030s, about 2 to 3 percent of projected consumption, according to government calculations.

Apparently oil industry leaders have been quietly lobbying for this action, including Marathon Petroleum Co., Koch Companies Public Sector LLC, and the refiner Andeavor. In fact, on the KQED Forum show I participated on this past Friday, one of the guests supporting the rollback was from the Koch-funded think tank “Pacific Research Institute.”

So it looks like Big Oil doesn’t really care if the auto industry twists in the wind on the rollback, if it means the possibility of selling a lot more climate-destroying oil in the meantime.

Battery electric buses are already cost-competitive with fossil-fueled buses, based on their lower fuel and maintenance costs. Transit agencies around the country are starting to purchase them in bulk from companies like BYD and ProTerra.

But is electricity really cleaner than a natural gas-fueled bus? Union of Concerned Scientists tackled this question in California previously and found positive results, per UCS’s Jimmy O’Dea, and now they’ve taken their research nationwide:

We answered this for buses charged on California’s grid and found that battery electric buses had 70 percent lower global warming emissions than a diesel or natural gas bus (it’s gotten even better since that analysis). So what about the rest of the country?

You many have seen my colleagues’ work answering this question for cars. We performed a similar life cycle analysis for buses and found that battery electric buses have lower global warming emissions than diesel and natural gas buses everywhere in the country.

Here’s the UCS map:

Meanwhile, the buses are getting cheaper and better, as ProTerra’s CEO Ryan Popple explained recently to E&E News [paywalled]:

Meanwhile, the buses are getting cheaper and better, as ProTerra’s CEO Ryan Popple explained recently to E&E News [paywalled]:

When we started out, we could really only do circulator-style routes, and we needed a fast charger for every route. That was probably five years ago, and that was because our maximum theoretical range was probably 50 miles. Now we’re regularly seeing our electric buses do anywhere between 175 and 225 miles in real service. And with all sorts of topography.

But despite the technological advancements and environmental benefits, supportive policy is still needed. Here’s the top of Popple’s policy wish list:

It is at the state of California, and it is the Innovative Clean Transit rule, the ICT. That is headed to the California Air Resources Board for an initial vote, I think, in September, and it could be fully implemented by the end of this year. What that ruling will do is set a long-term target for every transit vehicle in the state of California and a date certain by which it must eliminate its tailpipe emissions, so basically it has to become a zero-emissions vehicle… The reason it matters to us is just so that the industry can move forward with long-term planning on electric fleets.

And as more transit agencies move forward with zero-emission vehicles, we now have assurance that the clean air benefits are real — all across the country.

Two big questions arise for me from yesterday’s news of a proposed Republican carbon tax to be introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives soon.

First, it’s clear the proposal largely takes aim at the coal industry. That’s why most of the carbon reductions from the tax will come from the power sector, and why Big Oil is supposedly okay with such a tax. From Big Oil’s perspective, swapping out the gas tax with a carbon tax probably won’t make much of a difference to gas prices and therefore to consumer demand, and they’re not nearly as hurt by such a carbon tax as they would be with direct regulation and state-level mandates, as they currently experience in California with policies like the Low Carbon Fuel Standard.

From my perspective, it’s helpful to have policies to phase out coal. But if the coal industry is already largely on its way out anyway due to competition from cheap natural gas and renewables (particularly solar PV combined with energy storage technologies, both of which are in the midst of massive price decreases), then why the need for a tax to hasten their demise? Particularly when the political cost of that tax would be to halt diverse federal climate regulation and possibly preempt some effective state-level policies, like California’s AB/SB 32 greenhouse gas emission reduction laws?

Second, the vast majority of the revenue from this proposed carbon tax would go to the federal highway trust fund. But does it make sense to use carbon tax revenue essentially to subsidize more driving and associated pollution? A more logical way to fund the roads would be through a tax or fee on miles driven. That is not only a more fair approach (those who drive the roads more would then have to pay more to maintain them), it serves an environmental benefit of discouraging excess driving.

Right now there are no plans to replace the federal gas tax with a mileage fee. But states like Oregon and California are experimenting with them. If they can find suitable technologies to track miles, address the privacy concerns some have with government tracking these miles, and ensure a stable source of revenue for road maintenance, why not let these experiments play out and possibly transfer to the national stage as a more sensible gas tax replacement?

While a carbon tax might sound nice in theory, these types of details and political trade-offs matter. And in this case, climate advocates should have a lot of questions before they sign on to support such a policy.

The U.S. has long lacked a national strategy for reducing carbon emissions. To fill the void, various agencies have proposed a variety of regulations under existing laws, such as efforts to reduce methane emissions in oil-and-gas operations, limit carbon carbon emissions from the power sector (the Clean Power Plan), and promote environmental review of the greenhouse gas impacts of various federally approved projects.

With the death of a proposed federal cap-and-trade program in 2010 under a Democratic congress, some climate advocates now see hope in developing a national carbon tax. This approach makes a lot of sense: it could tax upstream emissions for carbon-based fuels like coal, oil and gas, thereby discouraging their use both by industry and by consumers, who may then seek to reduce consumption of things like coal-based electricity and gasoline for transportation. The revenue in turn could be used to fund various climate-friendly projects or be returned to taxpayers as a dividend.

Supporters actually include some Republicans, who prefer this more minimalist government approach to combating climate change instead of heavy-handed regulations or mandates, such as we see in states like California. To that end, a Florida Republican, Rep. Carlos Curbelo, is about to introduce a carbon tax proposal that is unlikely to go anywhere in this Congress but could serve as an opening salvo and building block for future policy.

E&E News received a copy of the legislation and had this to say about it:

A copy of the draft bill obtained by E&E News calls for eliminating the federal gas tax and replacing it with a $23-per-ton tax on carbon emissions from oil refineries, gas processing plants and coal mine mouths beginning in 2020. Industrial sectors such as cement, aluminum, steel and glass would also pay the fee for emissions stemming from physical or chemical reactions outside of energy production. Sources said Curbelo’s office was shopping that version of the bill last week.

…

It would halt — but not kill — EPA regulations on greenhouse gas emissions so long as the tax meets its goals to cut carbon emissions. The draft legislation contains check-in points in 2025 and 2029 to consider reinstating regulations if the tax hasn’t curbed enough greenhouse gases. The moratorium would sunset after 2033 if emissions goals are met. That provision is meant to address concerns from Democrats and environmental groups, which generally oppose forfeiting EPA’s authority to regulate carbon in exchange for a carbon tax.

Significantly, seventy percent of the revenues would go to the federal Highway Trust Fund to help shore up the dwindling gas tax revenue. The remaining revenue would go to state grants for low-income families to offset higher energy costs, research and development programs, and financing coastal restoration projects.

Meanwhile, companion research from libertarian-oriented think tanks modeled the greenhouse gas benefits. They suggest that emissions would drop 1.2 percent at a tax of $14 per ton, 3.2 percent at $50 per ton and 3.5 percent at $73 per ton. Cubelo’s research shows the policy would reduce greenhouse gas emissions 24 percent below 2005 levels by 2020 and 30 percent below 2005 levels in 2032, exceeding the targets for the U.S. under the Paris accord.

The modelers also claim the carbon tax would have negligible macroeconomic effects, with little change to U.S. GDP. The oil and gas sector would not be affected much, although transportation-sector emissions would generally drop 2 percent. The power sector would see much larger reductions, due to decreased reliance on coal-fired power plants.

The question for Democrats and other climate advocates is whether they would accept a national carbon tax that would displace the various climate regulations — and possibly preempt state action on climate. As my colleague Dan Farber noted on Legal Planet, jurisdictional and regulatory fragmentation on climate policy is advantageous to building political resilience. We’ve seen this play out in practice: the election of someone like Trump poses less of a threat when climate policies are embedded in multiple agencies, statutes, and state and local jurisdictions. A national carbon tax, while perhaps more effective in reducing emissions, flies in the face of that logic because it could swiftly be reversed by a future congress and president.

While decisions won’t have to be made soon on this bill, given the current political climate, climate advocates may soon have to grapple with the carbon tax option — and it’s potential political downside.

California has already achieved a landmark climate goal, we learned yesterday. Newly released data from 2016 by the California Air Resources Board show that the state’s greenhouse gas emissions decreased 2.7 percent to 429.4 million metric tons.

That number is significant because it’s below the 431 million metric tons the state produced in 1990, which is the level California law requires we achieve once again by 2020. And we’re now four years early on achieving that goal. Since our peak emissions in 2004, California has since dropped those emissions 13 percent.

Much of the reduction is due to significant increases in renewable energy production. Going forward, the next challenge will be a further 40 percent reduction below these 1990 levels by 2030, per SB 32 (Pavley, 2016). And that will require major decreases in emissions from the transportation sector — primarily through greater adoption of zero-emission vehicles.

Importantly, these emission reductions have occurred during a booming economy. The state has effectively de-linked economic growth from carbon-based energy. And all of this economic growth defies industry predictions back in 2006 when the 2020 goal in AB 32 was originally legislated.

As the Sacramento Bee reported at the time during the legislative debates:

[T]he measure [AB 32] is vigorously opposed by the California Chamber of Commerce and the petroleum industry.

”Climate change is real, and we do need to do things,” said Victor Weisser, president of California Council for Environmental and Economic Balance, which represents oil firms. ”But greenhouse gas emissions reduction in California is going to be very expensive.”

In short, industry was not pleased with the climate goals and believed they would cause economic calamity, as another Bee article related:

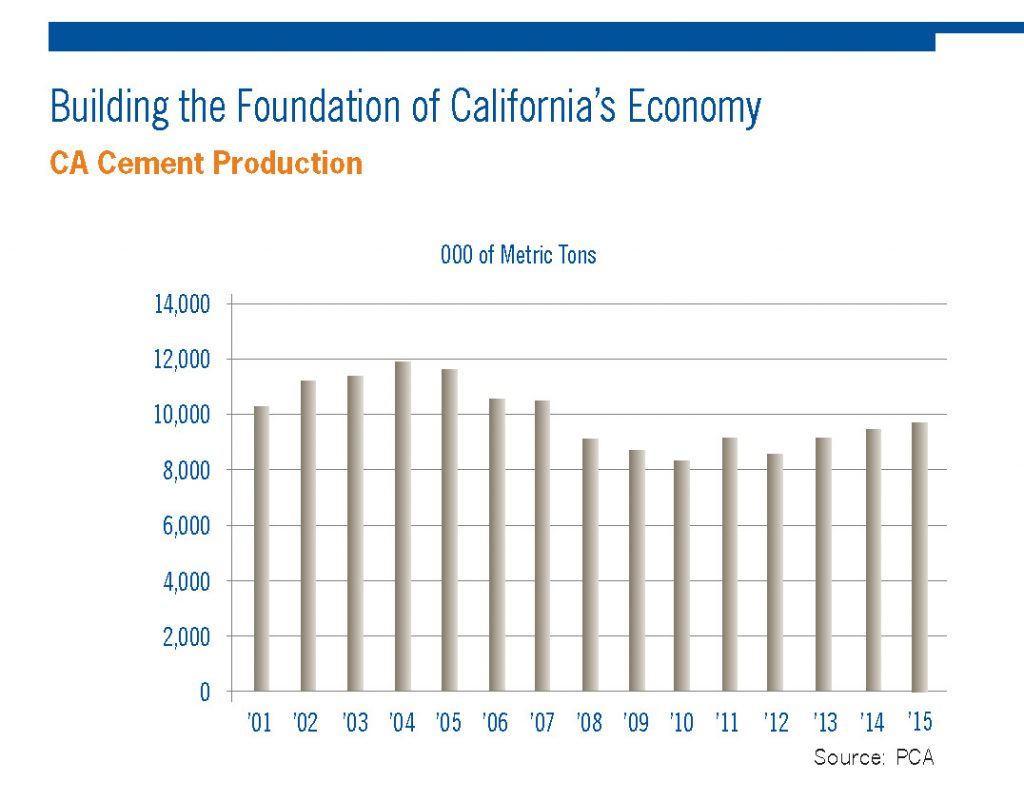

“We don’t think heavy-handed regulation and bureaucracy is necessary,” said Thomas Tietz, who heads the California Nevada Cement Promotion Council.

Backers say AB 32 would spur new technologies, but Tietz warned that such caps will backfire on the local economy. He said the bill would drive cement producers out of state and force California to import materials produced from countries or states with less stringent environmental rules.

In retrospect, these predictions have not come true. Cement production hasn’t left the state, as industry figures show (although the sector hasn’t fully recovered since the last recession):

Overall, California’s success is a powerful example for the rest of the world and some important good news in the global fight against climate change.

Overall, California’s success is a powerful example for the rest of the world and some important good news in the global fight against climate change.

With much of the credit due to the proliferation of inexpensive renewable energy, the next challenge will be to ensure similar progress with zero-emission vehicle technology. And given the state’s track record on climate so far, we should be hopeful that similar success is achievable for 2030.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez garnered a lot of publicity last month when the 28-year-old self-described “democratic socialist” from the Bronx beat longtime US representative Joe Crowley in the New York primaries. She is practically certain to win a seat in Congress in the general election this November.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez garnered a lot of publicity last month when the 28-year-old self-described “democratic socialist” from the Bronx beat longtime US representative Joe Crowley in the New York primaries. She is practically certain to win a seat in Congress in the general election this November.

While her economic policies have inspired the Democratic base, her advocacy on climate change is noteworthy. Specifically, she’s calling for a “Green New Deal” to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and transition our economy to one based on clean technology, like renewable energy. While she’s not the first politician to make this part of her platform (Jill Stein also tried), she may be the most high-profile at this point.

As E&E News reports [pay-walled]:

“What we are proposing is the complete mobilization of the American workforce to combat climate change and income inequality simultaneously,” Ocasio-Cortez told HuffPost. “The Green New Deal we are proposing will be similar in scale to the mobilization efforts seen in the World War II or the Marshall Plan. It will require the investment of trillions of dollars and the creation of millions of high-wage jobs.”

Among the specifics, she wants the U.S. to achieve 100 percent renewable electricity by 2035 and otherwise work to modernize the grid.

From my perspective, this bold advocacy is refreshing. It not only summons the urgency of the need to combat climate change, it transforms the solutions into a jobs and economic development strategy. Those economic benefits are both politically important to inspire regions of the country that need the jobs and also a logical and positive consequence of investing billions of dollars to modernize and clean our energy system, from the electricity to the transportation sectors and beyond.

I hope her advocacy will inspire other elected officials to follow suit. It could be a winning strategy for climate advocates in future elections.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy was a conservative justice, yet he occasionally voted with the four more mainstream justices on environmental issues. Presumably, his successor (if confirmed by this Republican-majority senate) will be more conservative. If that’s the case, here are three issue areas where a new Supreme Court could directly affect climate and energy progress:

- Federal Clean Power Plan: Kennedy was the crucial fifth vote on Massachusetts v. EPA, which held that the federal Clean Air Act required U.S. EPA to regulate greenhouse gas emissions as a pollutant. As a result of that ruling, the Obama Administration eventually proposed the Clean Power Plan, which would have compelled states to reduce carbon emissions from their power sectors. The regulation is tied up in litigation and likely to come before the U.S. Supreme Court. A new court could potentially overrule Massachusetts v EPA entirely or narrow EPA’s authority so much that it’s essentially meaningless. Notably, I believe the latter possibility would have been likely even with Kennedy on the bench.

- California’s waiver authority to regulate emissions beyond federal standards: the federal Clean Air Act allows California to set more aggressive standards than federal ones, provided EPA approves a waiver for the state to do so. Waivers were historically issued almost automatically, until George W. Bush came along and delayed approving one for California’s tailpipe emission standards. Now the Trump Administration is mulling going a step further: revoking previously granted waivers, such as the one to allow California to set tailpipe standards (which were harmonized with strong federal fuel economy standards under Obama, but since reneged on by Trump’s team). The U.S. Supreme Court will likely have to rule on EPA’s authority to revoke existing waivers, if Trump’s EPA chooses that course. The implications would be huge for California’s efforts to boost zero-emission vehicles.

- Regional grid management to promote clean technologies: the federal government has jurisdiction over wholesale power markets that cross state lines. So grid operators that seek to promote clean technologies, like renewable energy, energy storage, or demand response, often need federal agency approval. And the U.S. Supreme Court will occasionally hear cases on appeal. While the scope of these decisions is often narrow, they can affect regional efforts to reduce emissions from the power sector. A new court could potentially seek to undermine these efforts (although as E&E News describes [paywalled], these cases so far have been wonky and not subject to close partisan rulings by the justices).

Other cases could also affect climate policies, such as those involving federal agency regulation of methane emissions from oil-and-gas operations, as well as regulation involving other short-lived climate pollutants (described in E&E news [also paywalled]). But these three loom large for me.

Overall, Kennedy’s retirement is not good news for those who care about environmental protection, as I told the San Francisco Chronicle. But on the flip side, most of the action on climate right now is at the state and local level. Any federal progress will have to come from Congress, not from the courts. And that dynamic is now even more true now with Kennedy’s departure.

The City of Berkeley once had a reputation as a progressive, environmental leader. But now some members of its city council seem intent on preventing new development in this transit-rich, low-carbon city — an attitude that is both exclusionary and bad for the environment. The result is fewer transit riders and homes near jobs — and more sprawl and pollution as new residents are pushed far from the city center.

This issue is once again put to the test when the city council tonight debates whether to oppose AB 2923 (Chiu), a bill to allow BART to develop its own properties near station entrances. Berkeley is barely affected by the bill, as it would only allow new land use rules at one BART station: the parking lot at North Berkeley. Still, the NIMBY forces are out in effect for this resolution tonight.

Together with my UC Berkeley colleagues Karen Chapple and Elizabeth Deakin, along with Paulson Institute senior fellow (and Berkeley alum) Kate Gordon, I submitted a letter today asking the council to support AB 2923. Let’s hope the members support this innovative bill to allow badly needed new housing adjacent to major transit, so that others may enjoy the benefits that current Berkeley residents have.

It would not only be the right policy choice but an affirmation of the welcoming and open-minded spirit for which the city of my birth was once known.

UPDATE: The City Council approved the measure opposing AB 2923. The bill heads to the Assembly floor this week for a vote.

With all the focus on electric cars, it’s easy to overlook the impressive success that electric buses are having. The buses are more expensive than traditional diesel-powered buses (typically at about $700,000), but they have minimal operating costs due to low maintenance and relatively cheap electricity as fuel. As a result, they already present a strong value proposition to transit agencies.

With all the focus on electric cars, it’s easy to overlook the impressive success that electric buses are having. The buses are more expensive than traditional diesel-powered buses (typically at about $700,000), but they have minimal operating costs due to low maintenance and relatively cheap electricity as fuel. As a result, they already present a strong value proposition to transit agencies.

Electric buses also offer a significant environmental upside, both on carbon pollution and conventional air pollutants, as E&E News reported [paywalled]:

Converting the entire U.S. fleet of diesel transit buses — around 40,000 vehicles — to electric could avoid 2 million tons of greenhouse gas emissions each year, according to a recent report by Environment America, U.S. PIRG and the Frontier Group.

As transit agencies seek to retire old diesel buses, they are increasingly turning to zero-emissions technology, determining that it’s cheaper in the long run and provides significant public health benefits. Boesel estimates that around 5 percent of new U.S. bus sales are electric right now. Around 1 percent of new car sales are electric.

So not only are electric bus sales outperforming electric passenger vehicle sales right now, they are projected to dominate in the near future. Bloomberg New Energy Finance forcecasted electric buses to constitute 84% of new bus sales around the world by 2030, compared to 28% of new passenger vehicle sales by that same year.

We’ll be hosting the chief executives of two of the leading electric bus companies, Proterra and BYD, at our upcoming June 8th conference at UCLA on zero-emission freight at Southern California’s ports. Register now to hear more from them, as space is limited.