Housing policy is at the center of all of our major societal problems in the United States:

- Care about racial justice? Restrictive housing and land use policies are responsible for our deeply segregated towns and cities.

- Climate change? Bad housing policies are the reason why so many people are forced into long, emission-spewing commutes, because they can’t afford to live close to their jobs.

- Economic inequality? Inflated home prices and rents increasingly force middle- and low-income residents into low-opportunity areas, while shutting them out of the wealth-generating possibilities of home ownership. Just to name a few issues affected by housing.

So why can’t we address the high cost of housing, particularly near transit and jobs? There are two culprits: high-income homeowners who support exclusionary local land use policies that restrict housing supply, which prevents others from moving into their communities and deprives them of the educational and economic opportunities that come with living in these areas. Second, the state and federal government is unwilling to provide sufficient public subsidies for affordable housing (though the scale of the need at this point is simply massive, especially given the country’s inability to build housing at a reasonable price).

Perhaps with these dynamics in mind, then-Lieutenant Governor Gavin Newsom campaigned for governor in 2018, promising 3.5 million new housing units to address the state’s severe housing shortfall. But after two legislative sessions, the Governor so far has no meaningful legislative accomplishments on increasing housing production. Like 2019, this just-concluded 2020 legislative session proved to be a bust (yes, Covid-19 interfered, but housing was one of the few remaining priorities that the legislature was committed to addressing this year).

Here are the gory details of the housing bills from the original legislative “housing package” in January that did not survive:

Assembly defeats:

- AB 1279 (Bloom): would have identified high-resource areas with strong indicators of exclusionary patterns and require zoning overrides to encourage production of small-scale market-rate housing projects and larger-scale mixed-income affordable projects.

- AB 2323 (Friedman): would have expanded CEQA infill exemptions to projects in low-vehicle miles traveled (VMT) areas.

- AB 3040 (Chiu): would have incentivized cities to upzone to allow for fourplexes in neighborhoods currently zoned solely for single-family housing.

- AB 3107 (Bloom): would have allowed streamlined rezoning of commercial land for housing.

- AB 3279 (Friedman): would have amended administrative and judicial review for various projects under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA).

Senate defeats:

- SB 899 (Wiener): would have streamlined review for religious institutions seeking to build housing on their property.

- SB 902 (Wiener): would have streamlined approval for up to 10 housing units per parcel near transit.

- SB 995 (Atkins): would have fast-tracked CEQA review for environmentally beneficial infill projects.

- SB 1085 (Skinner): would have expanded density bonus law by allowing rental housing developers to increase the size of their projects 35% if at least 20% of the units were moderately priced (rent at 30% below market rate for the area).

- SB 1120 (Atkins): would have allowed two homes on every property zoned for single-family homes in California; would have also allowed single-family properties to be split into two lots.

- SB 1385 (Caballero): would have made it easier to rezone commercial land for housing and streamline approval for projects on that land.

- SB 1410 (Caballero): would have provided rental relief through tax credits to landlords to fill unpaid rent.

It’s also worth reiterating that the senate voted down in January an amended version of Senate Bill 50 (Wiener), which would have reduced local restrictions on apartments near major transit and jobs.

And strangely, SB 995, SB 1085, and SB 1120 all passed the Assembly at the last minute, but Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon scheduled the vote too late for a concurrence vote in the Senate. As a result, the bills died.

But the news was not all bad. Some housing bills did pass, including:

- AB 725 (Wicks): requires that no more than 75 percent of a city’s regionally assigned above-moderate income housing quota can be accommodated by zoning exclusively for single-family homes, with the remainder on sites with at least 4 units.

- AB 1851 (Wicks): requires local governments to approve a faith-based organization’s request to build affordable housing on their lots and allows faith-based organizations to reduce or eliminate parking requirements.

- AB 2345 (Gonzalez): increases the density bonus and the number of incentives available for a qualifying housing project.

- SB 288 (Wiener): temporarily exempts from CEQA review infill projects like bike lanes, transit, bus-only lanes, EV charging, and local actions to reduce parking minimums, among others, until 2023 (disclosure: I helped Assemblymember Laura Friedman and Assembly Natural Resources Committee chief consultant Lawrence Lingbloom draft the parking provision, along with Mott Smith of the Council of Infill Builders).

So there we have it in 2020. A few successes, but mostly a wipeout. Perhaps recognizing the urgency after two failed sessions, Governor Newsom appeared this week to offer something of a belated endorsement of SB 50 and SB 1120, two of the more consequential bills that failed in the legislature this year:

But absent strong leadership from the Governor’s office and legislative leaders, this pattern of failure on housing production will likely continue, exacerbating all the challenges I discussed above that are affected by dysfunctional housing policy. That means we can expect worsening racial injustice and segregation, greenhouse gas emissions, and economic inequality, to name just a few, until the state can finally, meaningfully address this problem.

Jim Mahoney was perhaps an unlikely climate hero. A senior Bank of America and FleetBoston Financial executive for 25 years who tragically passed away this past weekend at the age of 67 (the result of complications from injuries he sustained in a bicycle accident last year), Jim’s work focused on global corporate strategy and public policy for a major financial institution. Climate change would have been just one component of his portfolio of issues affecting banking.

But back in 2008, Jim teamed up with his former boss, then-California Attorney General Jerry Brown, to make a difference on climate policy. Brown and Mahoney, through Brown’s then-climate advisors Ken Alex (now with Berkeley Law) and Cliff Rechtschaffen (now a California public utilities commissioner), approached Rick Frank (now with UC Davis Law) and Steve Weissman (now with the Goldman School) at UC Berkeley Law and Sean Hecht and Cara Horowitz at UCLA Law to launch a Climate Change and Business Initiative at the law schools.

The initiative was only planned for one year, to focus on then-emerging topics in climate policy like infill housing, small-scale renewable energy, low-carbon agricultural practices, and residential energy efficiency financing. The idea was to convene small groups of experts for roundtable discussions that would inform policy reports on business solutions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. These reports in turn would ideally educate California legislators and regulators on cutting-edge, consensus climate solutions.

But with Jim’s quiet but committed leadership at Bank of America, that one-year initiative soon grew to a multi-year program that has to this day covered multiple climate and clean energy issues and influenced legislation and regulation in California and throughout the country. Here are just a few highlights:

- Pioneering climate and clean energy legislation: The initiative helped inform the California’s first-in-the-nation energy storage mandate, which proved so successful that the initial targets have been increased and expanded. It also inspired legislation to streamline permitting for utility-scale solar PV on degraded agricultural land, as well as to increase California’s renewable energy requirements.

- Regulation and funding: Recent work on boosting energy retrofits for low-income multifamily buildings was incorporated into state energy planning, while a biofuels convening helped steer millions of dollars of state energy funding for this low-carbon industry.

- Inspiring out-of-state action: A number of the in-state policy recommendations have informed similar work elsewhere, such as our stakeholder process to identify prime areas for renewable energy development. And in general, California legislation on climate and energy has inspired similar action across the United States, particularly on renewable energy and zero-emission vehicles.

- Cataloguing climate solutions: All of the initiative’s recommendations over the years are compiled in the easy-to-use website climatepolicysolutions.org.

- Influencing public debate: In addition to convenings and reports, the initiative has led to publication of numerous op-eds (most recently on ways to make the electricity grid more resilient and low-carbon), webinars (such as on priority climate solutions with California’s top climate leaders), and conferences (including recently on expanding zero-emission freight technologies at Southern California’s ports).

- Training future climate leaders: Throughout the research involved with this initiative, the law schools have included numerous law students and recent graduates to help conduct that work. Many of them have gone on to further this work through their professional employment at law firms, clean technology companies and government agencies, among others, with one recent fellow now advising the Biden campaign on climate policies.

And on a personal note, Jim’s initiative provided me with an opportunity to dedicate my career to working on all of these important issues, as I was first hired at Berkeley Law for that one-year initiative before eventually directing the climate program at the law school’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE).

While many individuals have been involved in the Climate Change and Business Initiative over the years, none of this work would have been possible without Jim’s leadership at Bank of America. Along with his colleagues, including Rich Brown, Brian Putler, Kaj Jensen, Alexandra Liftman, and others, Jim ensured that the initiative had strong institutional support and funding to carry out this work, without ever interfering or trying to influence the content of what the initiative covered or recommended. Quite the opposite, he helped the law schools’ harness the Bank’s expertise and contacts to further the dialogues and reach of the findings.

Jim’s death is a blow to his family, friends, colleagues, and those of us who care about the issues he helped advance. The Boston Globe published a worthy tribute to his career and extensive family, including his volunteer stint driving then-presidential candidate Jerry Brown around New Hampshire and Wisconsin.

Jim will be missed, but his legacy of climate leadership will live on in the work and policies he helped advance, and in the lives he touched. May he rest in peace.

On January 27, 2017, just one week after Trump’s inauguration, UC Berkeley Law’s Henderson Center for Social Justice held a daylong “Counter Inauguration,” featuring various panels in reaction to Trump’s victory. I spoke on an afternoon panel that day entitled “Monitoring the Environmental, Social and Governance Impacts of Business in the Trump Era” and offered my predictions on what the Trump years would bring for environmental law and policy.

I recently reviewed these predictions, three months out from the upcoming November election, to see how they measured up against the reality of Trump’s near-complete term in office. Bottom line: these predictions mostly tracked with what happened with Trump and his administration’s leaders, albeit with some steps I missed, some that never came to pass, and some positive outcomes for environmental protection.

First, I predicted the Trump Administration would follow through on the campaign pledges to boost fossil fuels in the following ways:

- Opening up public lands for more oil and gas extraction

- Slashing regulations that limit extraction and related pollution, such as the Clean Power Plan and methane rules

- Weakening fuel economy rules for passenger vehicles

- Financing more infrastructure that could boost automobile reliance (i.e. more highways and less transit)

These were all relatively predictable actions, and they all pretty much happened as predicted. On public lands and fossil fuels, Trump rolled back National Monument protection at Utah’s Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante, as well as streamlined permitting for oil and gas projects on public lands. On environmental rules in general, here is a list of 100 environmental regulations that the administration has tried to reverse. On vehicle fuel economy standards, here’s my article on EPA’s proposed rollback. And transit funding went from 70 percent of transportation grants under Obama to 30 percent under Trump, with the rest funding highways.

Second, I predicted that his administration would try to undermine clean technologies by:

- Weakening tax credits for renewables and electric vehicles

- Undoing federal renewable fuels program

- Revoking California’s ability to regulate tailpipe emissions

- Attempting to undermine California’s sovereignty to regulate greenhouse gases through legislation

- Cutting funding for high speed rail and urban transit

- Withdrawing from Paris agreement

On these predictions, I was correct on most accounts. The administration did weaken tax credits for renewables (both by not extending them or preventing them from decreasing over time, save for a recent one-year extension on wind energy as a budget compromise) and electric vehicles (by letting them expire and threatening to veto Democratic legislation that would have extended them in a recent budget bill). His EPA did revoke California’s waiver to issue tailpipe emission standards. And he famously withdrew from the Paris agreement (to take actual effect later this year) and has tried to cancel almost $1 billion in high speed rail funding in California.

But I was incorrect that the administration would pursue legislation to preempt California’s (and other states’) sovereignty to set their own climate change targets. There was little appetite in Congress to do so, though Trump’s Justice Department did seek unsuccessfully to declare California’s cap-and-trade deal with Quebec to be unconstitutional. And his record on renewable fuels is more mixed but did deliver some gains to corn-based ethanol producers, though the environmental benefits are suspect with this type of biofuel. I also failed to predict the administration’s efforts to impose tariffs on foreign solar PV panels and wind turbines, which slowed those industries somewhat.

Finally, I predicted some possible bright spots for the environment in the Trump years, much of which did occur:

- Clean tech generally has bipartisan support in congress

- Infrastructure spending in general could be negotiated to benefit non-automobile investments

- Lawyers can stop or delay a lot of administrative action on regulations

- A shift will happen now to state and subnational action on climate, which probably needed to happen anyway

Sure enough, clean technology, particularly solar PV, wind and batteries, has continued to increase in the Trump years, though not at the same pace as under Obama due to the policy headwinds. But infrastructure spending has definitely favored automobile interests, as noted above.

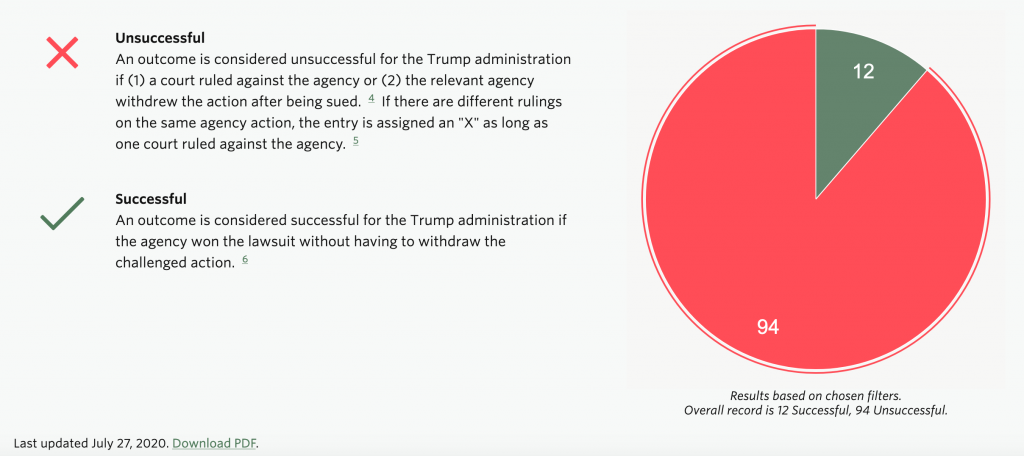

But more importantly, two critical predictions did come to pass. First, attorneys have successfully stopped most administrative rollbacks. In fact, the administration has an abysmal record defending its regulatory actions in court. As NYU Law’s Institute of Policy Integrity has documented, the administration has lost 94 cases in court and won only 12 to date, as tracked in this chart:

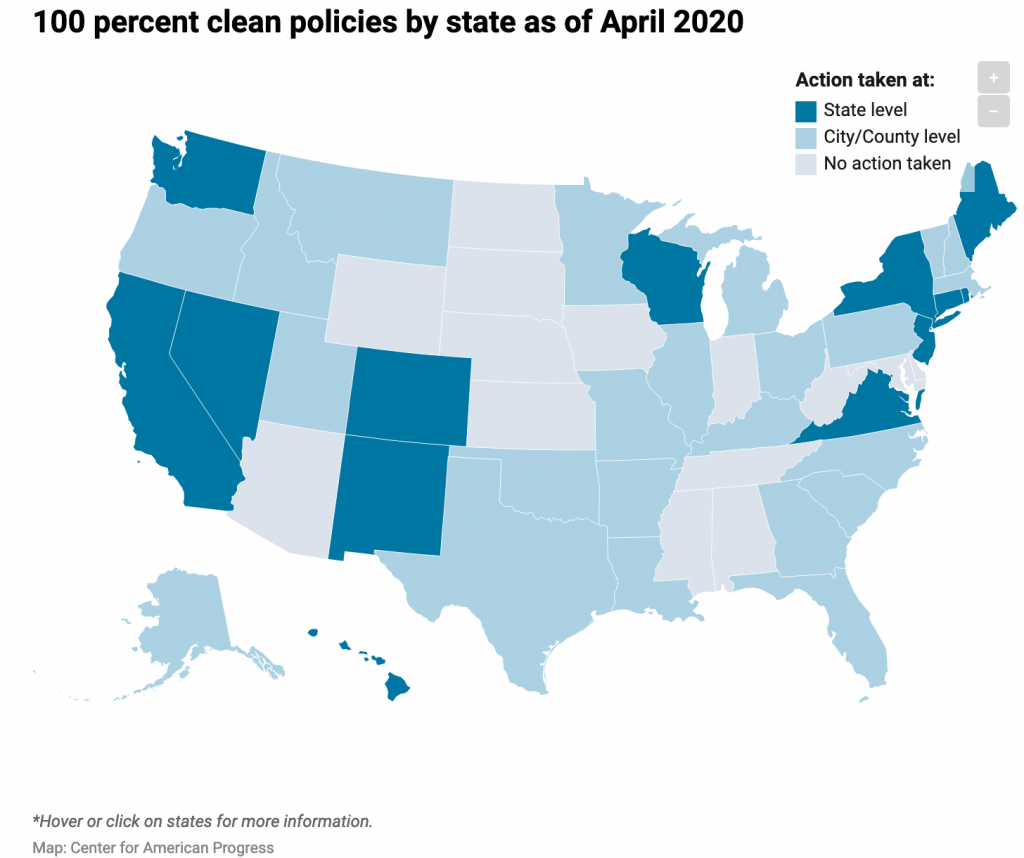

And perhaps more importantly, the lack of federal climate action has moved the spotlight to state and local governments, which often have significant sovereignty to enact aggressive policies that add up to serious national climate action. Take renewable energy, for example, per the Center for American Progress, with this map of states and municipal governments that have enacted 100% clean electricity standards:

And on clean vehicle standards, 13 states plus the District of Columbia now follow California’s aggressive zero-emission vehicle standards, representing about 30 percent of the nation’s auto market.

As a result, in many ways, environmental law and climate action appears to have survived the Trump term in office mostly intact, despite losing progress and facing some setbacks on key issues. Most of the regulatory actions can be reversed by a new administration, while Congressional action during the Trump years was relatively minimal in scope. Meanwhile, the counter-reaction to Trump spurred some significant policy wins at the state and local level.

But while one term is perhaps survivable for environmental law and climate progress, a second one could paint a completely different picture. So the stakes certainly remain high this November.

California law under SB 100 (De León, 2018) requires that our electricity system run on 100% carbon-free power by 2045. That means a significant deployment of energy storage resources, like batteries, to capture surplus renewable power from the sun and wind for dispatch during dark and windless times.

While passing this law was a milestone, actually achieving this target will require siting and permitting major clean energy facilities. And perhaps no better land is appropriate for these facilities than at existing fossil fuel plants. These plants are on already-industrialized land with access to transmission lines. Converting them to energy storage facilities is a double-win: it offers a phase out of fossil fuels, while improving the air quality (and often the aesthetics) of the surrounding area.

So that’s why it’s frustrating to see one such proposed conversion to battery storage — the Moss Landing power plant battery energy storage project — potentially held up for months now by local opposition. The Monterey County Planning Commission will consider the project at its July 29th hearing.

The proposed project involves a 1,200-megawatt (MW) battery energy storage system, fit into the existing industrial footprint of the Moss Landing power plant in four two-story buildings, along with associated infrastructure (substations and inverters/converters). It will also replace existing lattice transmission towers with monopoles (staff report available here).

Most importantly, the goal of the project is to store renewable energy from the sun and wind to help California decarbonize its electricity grid. For this reason, Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E, the local utility) selected the project and brought it to the California Public Utilities Commission for approval, with a condition that the project reach commercial operation by July 18, 2021 (PG&E advice letter here).

But a good proposal to support needed climate policy is not always enough in California. Permitting any industrial project comes with challenges and opposition, most notably compliance with environmental review under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA).

In this case, a review of the project under CEQA by the county revealed no significant impacts on the myriad study areas, including air quality, biological resources, water, traffic, cultural resources, and others; provided the developer implement appropriate mitigation measures. However, the developer ended up going beyond the county’s recommendations by committing to a dialogue process to identify additional mitigation measures to protect migratory birds. In short, the developer agreed to go above and beyond what CEQA requires.

Furthermore, in collaborating with the National Audubon Society and Monterey Audubon, the developer agreed not to include new transmission poles and high-voltage wires until after 2020, at which point they will conduct final design in consultation with those nonprofits. The company further committed to addressing bird safety issues in that process, including consideration of undergrounding high-voltage transmission wires.

Ultimately, the clean energy nature of the project, the county’s preparation of an environmental review document that follows CEQA, and this additional commitment to address bird safety issues were enough to gain the support of Audubon and the Sierra Club. The project appeared to face relatively easy sailing to a permit, but the planning commission delayed considering it at its July 8th meeting so that the environmental review document could be revised to clarify transmission wire placement associated with the project. Hopefully, the commission approves the project on July 29th, and no one appeals it to the Monterey County Board of Supervisors.

If California can’t allow relatively straightforward permitting of energy storage facilities at existing power plants with minimal anticipated impacts, where can they go? Not only will clean tech companies shy away from investing in California, potentially driving up costs from lack of competition, but these eyesore power plants may take longer to decommission. In the case of Moss Landing, the power plant has 500-foot dual smokestacks visible through Monterey Bay, a source of visual blight and air pollution in an otherwise unique marine and coastal environment. This battery storage project could help facilitate this decommissioning sooner rather than later, while embodying precisely the critical energy storage deployment California needs to achieve a decarbonized future.

CLEE and the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) are pleased to release today the new report “Sustainable Drive, Sustainable Supply: Priorities to Improve the Electric Vehicle Battery Supply Chain.” The report identifies key challenges and solutions to ensure battery supply chain sustainability through a multi-stakeholder approach, based on our outreach to experts in the field.

The global transition from fossil fuel-powered vehicles to battery electric vehicles (EVs) will require the production of hundreds of millions of batteries. This massive deployment frequently raises questions from the general public and critics alike about the sustainability of the battery supply chain, from mining impacts to vehicle carbon emissions.

To address these questions, CLEE and NRGI are conducting a stakeholder-led research initiative focused on identifying strategies to improve sustainability and governance across the EV battery supply chain. CLEE and NRGI convened leaders from across the mining, battery manufacturing, automaker, and governance observer/advocate sectors, to develop policy and industry responses to human rights, governance, environmental, and other risks facing the supply chain.

“Sustainable Drive, Sustainable Supply” identifies the following key challenges to ensuring battery supply chain sustainability:

- Lack of coordinated action, accountability, and access to information across the supply chain hinder sustainability efforts

- Inadequate coordination and data sharing across multiple supply chain standards limit adherence

- Regulatory and logistical barriers inhibit battery life extension, reuse, and recycling

The report recommends the following priority responses that industry, government and nonprofit leaders could take to address these challenges:

- Industry leaders could strengthen mechanisms to improve data transparency and promote neutral and reliable information-sharing to level the playing field between actors across the supply chain and between governments and companies

- Industry leaders and third-party observers could ensure greater application of supply chain sustainability best practices by defining and categorizing existing standards and initiatives to develop essential criteria, facilitate comparison and equivalency, and streamline adherence for each segment of the supply chain

- Governments and industry leaders could create new incentives for supply chain actors to participate in and adhere to existing standards and initiatives, which may include sustainability labeling and certification initiatives

- Industry leaders could design batteries proactively for disassembly (enabling recycling and reuse), and industry leaders and governments could collaborate to build regional infrastructure for battery recycling and transportation and create regulatory certainty for recycling

We hope the responses to the supply chain challenges outlined in this report will provide guidance on the initial actions stakeholders can take to make this broader vision of implementation a reality, ensuring a more robust future for communities around the globe as well as for all-important electric vehicle adoption to meet climate change goals.

To learn more about this issue and the new report, join our 9am PT / Noon ET webinar today, featuring:

- Patrick Heller, Senior Visiting Fellow, Center for Law, Energy & the Environment (CLEE) & Advisor, Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI)

- Michael Maten, Automotive Public Policy, Electrification, Portfolio Planning and Strategy, General Motors

- Daniel Mulé, Senior Policy Advisor for Tax and Extractive Industries, Oxfam

- Payal Sampat, Mining Program Director, Earthworks

You can register for the webinar; read our recent FAQ on EV batteries for more information on current supply chain impacts on human rights, climate change and the local environments; and download the new report “Sustainable Drive, Sustainable Supply: Priorities to Improve the Electric Vehicle Battery Supply Chain.”

Note: this post is co-authored with Ted Lamm.

California’s electrical grid is at the center of our fight against climate change, with aggressive goals to decarbonize through renewable energy. But the grid is at risk as climate impacts become more severe, particularly from worsening wildfires. To help modernize the grid to be cleaner and more resilient, the state will need deployment of clean technologies such as distributed renewable generation, microgrids, energy storage, building energy management, and vehicle-grid integration.

Part of the vulnerability of the grid stems from its role in exacerbating climate impacts. Most prominently, power lines sparked many of the record-setting wildfires of 2017 and 2018, including the Camp Fire that destroyed the town of Paradise. To minimize this threat during high-risk weather conditions, California electric utilities and energy regulators have begun to implement preemptive power shutoffs. In 2019, widespread PSPS events likely contributed to a safer wildfire season, but the days-long shutoffs also left some vulnerable communities and residents without access to essential health and safety services.

At the same time, many residents turn to fossil-fuel backup generators during grid shutoffs, which both polluting (in terms of both greenhouse gases and locally harmful air pollutants) and unaffordable for many Californians. But the alternative—deploying clean, resilient distributed resources, such as home batteries, community solar, or microgrids—will require significant policy and financial support for grid managers, electric utilities, community choice aggregators, and local governments.

To address this need, CLEE and UCLA’s Emmett Institute convened a group of California state energy regulators, local government leaders, grid experts, and clean energy advocates for a convening on California’s electrical grid of the future. CLEE and Emmett are today releasing a new report, Clean and Resilient, based on this expert group’s findings.

The report highlights the top policy solutions the group identified to address the financial, regulatory, and data barriers to clean, resilient grid deployment, including:

- Promoting performance-based regulation at the California Public Utilities Commission, to ensure that the public benefits and necessity of investments in reliable, carbon-free technology are fully accounted for.

- Reforming grid interconnection processes (including CPUC Rules 2 and 21) to create a presumption in favor of new microgrids and other distributed technologies and to equitably share the cost of associated grid upgrades.

- Initiating a new energy data collection and management process at the California Energy Commission to ensure communities, technology providers, and regulators have access to the data that will drive the grid of the future.

You can access the report and its full set of policy recommendations here. Ultimately, developing the clean and resilient electrical grid California needs will rely on a suite of parallel initiatives, from building and vehicle electrification to advanced data and communications development, each of which will require additional support. Given the range of these interconnected efforts, and the urgency of our statewide need for a safe, reliable grid, developing coordinated policy processes to promote them is becoming increasingly essential.

The Trump Administration finally released in March its long-planned rollback of federal fuel economy standards, a gift to the oil industry and its allies. However, the rollback is riddled with errors that will lead to a lengthy court battle and could be halted by a new president next January. Furthermore, long-term industry trends and international efforts to promote cleaner vehicles may make the rollback meaningless.

I detail the administration’s rule-making and the potential for more optimistic outcomes in a new opinion piece published today by the Regulatory Review at University of Pennsylvania Law School. The stakes for the climate fight, given the centrality of transportation emissions to overall greenhouse gas emissions, couldn’t be higher.

Interested in learning about policy options to phase out California’s oil and gas production? Join me and Ted Lamm today at 11am Pacific Time as we present findings from the new CLEE report Legal Grounds. We will discuss the background of oil and gas production in California and key law and policy opportunities to begin a phase-out in order to meet climate and environmental goals.

Also joining us on the webinar will be:

- Ann Alexander

Senior Attorney, Dirty Energy, Lands Division, Nature Program

Natural Resources Defense Council - Ingrid Brostrom

Assistant Director

Center on Race, Poverty & the Environment - Sean B. Hecht

Co-Executive Director, Emmett Institute on Climate Change and the Environment

UCLA School of Law

It might seem obvious that phasing out oil and gas production in California would benefit the climate. But the reality is much more complicated, in terms of emissions, economics and even geopolitics.

CLEE just released the report Legal Grounds with policy options to reduce in-state production, but the question of how much a phase out would benefit the climate was mostly beyond the scope of our analysis (which we’ll be discussing in more detail on a free webinar on Tuesday, May 12th, at 11am). However, it’s a question worth examining in more detail.

The challenge is that demand for fossil fuels in the state will remain for the foreseeable future, even if local production ceases. If we stop producing oil here, we’ll start importing more from elsewhere.

While California’s oil demand is already decreasing due to market and policy factors, until consumers completely transition to zero-emission vehicles and find alternatives to petroleum-based products like plastic and asphalt — and until refineries in the state stop exporting to markets around the Pacific — the supply will still find its way to the state. If that oil comes from out-of-state sources, the carbon footprint may even be higher than if California produced it domestically due to shipping emissions.

However, economic theory indicates that a decrease in California production will mean some decrease in consumption, as global prices will rise slightly from reduced overall supply. One study indicated it could lead to global emission reductions of 8 to 24 million tons of CO2 per year. And any oil left in the ground is oil not burned in the long run, meeting one of the highest priorities of climate activists. So a California phase-out could help avoid some emissions, though the rate is unclear.

What about the political implications of phasing out oil and gas consumption for climate policy? One argument is that a phase-out here might inspire other jurisdictions to follow suit. As most climate models indicate that some percentage of fossil fuels will have to remain untapped as an imperative for avoiding the worst of climate change, why not start in California, a state committed to climate action? It might be hard to imagine that top oil-producing countries like Saudi Arabia, Iraq and Iran (or other U.S. states) would be so inspired, but perhaps places like Norway or Colorado might be more politically open to it. And if the oil industry in California phased out, its lobbying power might also wane, allowing the state to pursue more aggressive policies on the demand side.

The economic impacts of a phase-out for climate policy are also complicated. As Severin Borenstein at UC Berkeley Energy Institute at Haas blogged in 2018, a phase-out in California would mean slightly higher worldwide oil prices, which would in turn enrich the major oil producing companies and countries who are still providing supply. As he summarized:

One could think of this as similar to a very small worldwide carbon tax, except in this case the revenue is not rebated to the population as a whole or used to reduce other taxes, but rather handed to those who own and control the world’s oil production

But there is one clear benefit from phasing out in-state oil and gas production in California: improved health and safety of surrounding communities. Scientists have linked drilling for oil and gas to numerous public health challenges, including increased rates of asthma, cancer, and other health threats. And much of the drilling in California occurs in or near residents of disadvantaged communities, adding to the urgency.

Another certainty is that California is firmly committed to reducing demand for fossil fuels, through boosting zero-emission vehicles, requiring lower-carbon fuels, and pricing carbon through cap and trade. As this activity increases, it will put pressure for corresponding reductions on the supply side, regardless of any other uncertainties involved.

So while the benefits of a phase-out of California production may be somewhat unclear in terms of avoided carbon emissions, the health and safety value is clear. California’s ability to manage the process with a careful, just transition could demonstrate a viable path forward for this long-term climate effort.

The COVID-19 virus and global response has sparked massive changes in our economy and every day lives. There is a lot conjecture about how this experience may shape long-term responses to climate change, from a crashing oil and gas market to the potential for the public taking scientific projections of calamity more seriously.

I’m mostly pessimistic about how the virus and our response to it will shape long-term climate change efforts. My guess is that life will mostly return to our normal fossil fuel-burning ways once the pandemic eases. And in the short term, the economic recession will undermine clean tech investment, while virus panic will hurt transit ridership and possibly undercut support for urban living.

But there’s one potential bright spot for the climate that may outlive this current era: working from home. Prior to the pandemic, only 4% of U.S. employees worked from home, according to Global Workplace Analytics. But now more than half of the 135-million people in the U.S. workforce is setting up in a home office.

The firm estimates that at this rate, by the end of next year 25% to 30% of the total U.S. workforce will be telecommuting, the carbon equivalent of “taking all of New York’s workforce permanently off the road,” per Kate Lister, president of the firm.

From a greenhouse gas perspective, it means many fewer driving miles from commuting. Otherwise, approximately 86% of Americans drive to work, according the National Household Travel Survey. If just 25% of Americans began teleworking even one day per week after the pandemic, total vehicle miles traveled would fall by 1%, which is actually a significant amount of the more than 3.2 trillion miles driven in the U.S. in 2018. The numbers could go much higher if telecommuting were multiple days per week for more people.

And why might these work from home habits stick, as opposed to other environmental friendly measures taken during the pandemic? Simple: working from home is more convenient and productive for most people. But prior to the pandemic, many managers weren’t comfortable allowing the practice, believing (falsely) that it would hurt bottom lines.

But now that everyone who can work from home is forced into this arrangement without calamity, my guess is that this manager resistance will fade. And any employees who might have guessed they wouldn’t enjoy working from home may also be finding that there are significant upsides, which would lead them to agitate for supervisor permission to continue the practice.

Telecommuting by itself won’t solve transportation emissions, but it could set the stage for further reforms, such as dedicating more public spaces like streets for pedestrians and bicyclists, as European cities are now contemplating. After all, people working at home will want to take walks and get out for exercise, and in cities that means streets will need to be converted.

In addition, telecommuting may solidify the current practice of transitioning work travel and conferences to on-line events and meetings. If people are already comfortable working at home, they may be more likely to continue participating in panels and meetings remotely, too, which will reduce car and plane flights.

Perhaps there will be other long-term climate benefits from COVID-19. But to my mind, working from home seems like the most obvious candidate for a pandemic culture-changer that reduces emissions.