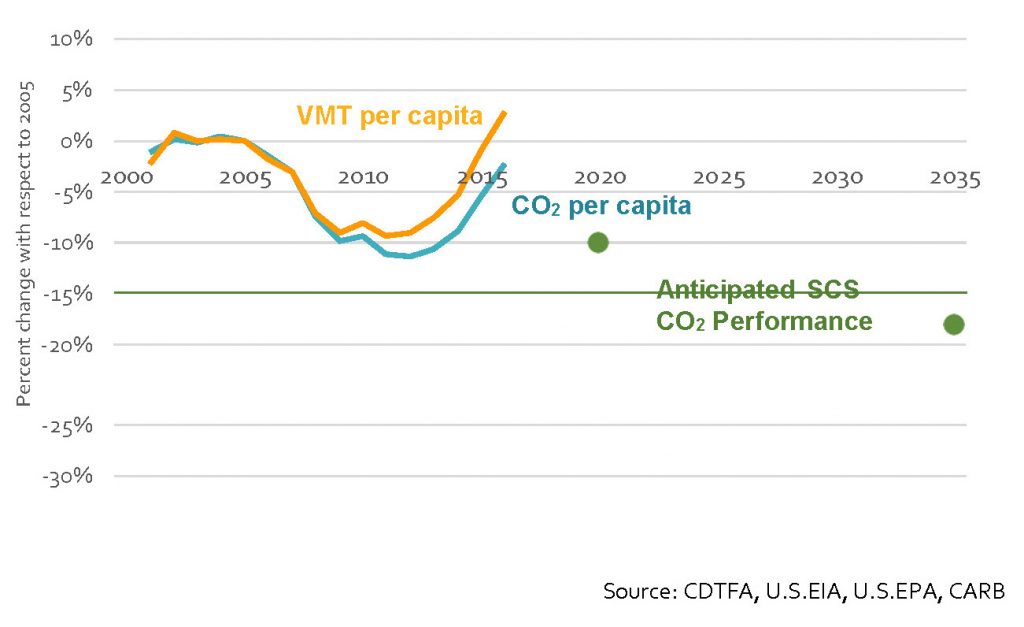

California’s major urban regions are falling behind in getting people out of their solo drives in favor of walking, biking, transit and carpooling, according to a major report last month from the California Air Resources Board. In short, the state will not meet its 2030 climate goals without more progress on reducing vehicle miles traveled (VMT):

This result comes despite the decade-old passage of SB 375 (Steinberg, 2008), which promised to reorient land use and transportation around reduced driving. The lone exception appears to be the San Francisco Bay Area, which has seen steadily increasing transit ridership and decreasing solo driving to work as a percentage, according to the report.

This result comes despite the decade-old passage of SB 375 (Steinberg, 2008), which promised to reorient land use and transportation around reduced driving. The lone exception appears to be the San Francisco Bay Area, which has seen steadily increasing transit ridership and decreasing solo driving to work as a percentage, according to the report.

What are the stakes if California can’t start solving this problem in the next decade? A U.N. report on climate change recently concluded that limiting global warming to 1.5 C would “require more policies that get people out of their cars — into ride-sharing and public transportation, if not bikes and scooters — even as cars switch from fossil fuels to electrics.” In order to keep the world on track to stay within 1.5 Celsius, the report stated that emission reductions would have to “come predominantly from the transport and industry sectors” and that countries couldn’t just rely on zero-emission vehicles alone.

Yet as the report shows, California’s current land use policies are not helping with this goal. We need to discourage development in car-dependent areas while promoting growth close to jobs, as SB 50 would allow. And at the same time, we need to invest in better transit service. Otherwise, California and jurisdictions like it around the world will fail to avert the coming climate catastrophe.

To meet long-term climate goals, we’ll need eventual 100% zero-emission vehicle adoption. But it’s not just new vehicle sales that matter. It’s becomingly less expensive to retrofit existing vehicles, including even this 1949 Mercury Coupe, pictured here:

![]()

As Autoweek profiled, Jonathan Ward and the Los Angeles-based Icon converted a fuel-injected Coyote V8 into an EV, installing two motors and a Tesla-sourced 85 kWh battery system with up to 200-mile range.

It was carefully done work, as you can see under the hood:

![]()

Some big wins for California (and therefore national) climate policy last night:

Some big wins for California (and therefore national) climate policy last night:

- Lt. Governor Gavin Newsom is elected governor, which means the state will continue its climate leadership on various policy fronts

- Prop. 6 loses, which would have repealed the gas tax increase and meant less funding for transit going forward

- Prop. 1 wins, which could provide more money for affordable housing in infill areas, reducing driving miles as a result

- The Democrats win the U.S. House of Representatives, which has a host of implications:

- Oversight of the U.S. Departments of Energy, Interior, and Transportation, plus E.P.A., which have all issued various regulations that hurt climate goals in the state

- Potentially more funding in future budget bills for crucial transit infrastructure, including high speed rail

- Potentially more funding and fiscal support for clean tech, like renewables, energy storage and electric vehicles, depending on how budget negotiations proceed

- Oregon Governor Kate Brown wins re-election, which means that state is well-positioned to adopt cap-and-trade next year, making it the first U.S. state to link to California’s program and potentially creating a multi-state building block for an eventual national carbon trading program

And on the housing front, Governor-elect Newsom has set ambitious goals for building more homes in the state, which if done in infill areas could bring crucial climate and air pollution benefits from reduced driving per capita. Pro-housing “YIMBY” candidates also bolstered their ranks in state government, with the election of former Obama campaign staffer Buffy Wicks to the Berkeley Assembly district.

Setbacks nationally (beyond continued Republican gains in the U.S. Senate) included the defeat of some state ballot initiatives, including a carbon tax in Washington, an anti-fracking measure in Colorado, and a renewable portfolio initiative in Arizona — though Nevada voters did embrace a 50% renewable target by 2030 at their polls.

All in all, a positive night for climate policy in California and beyond.

Rural America has been falling behind urban America for decades, in terms of economic productivity and population growth. The worsening divide has manifested in cultural and political disruption nationwide. What role can climate policy play to help repair the inequity and hollowing out of our rural places?

My colleague Dan Farber describes the stark situation in Legal Planet:

According to Brookings researchers, the 53 largest metros account for over 95% of the nation’s population growth and 73% of the employment gains since 2010. Rural areas—those with no metros over 250,000 –are losing population and account for a declining share of the national economy. In other words, Brooking says, “9 percent of the population lives in smaller metros that are stagnant or slipping as a group and another 14 percent in rural places that are almost all declining.” It’s not hard to see why people are unhappy.

He then cites some of the ways that climate and environmental policy could help. First, rural areas will be disproportionately affected by a changing climate, particularly to agriculture. So they may be amenable to policies that address these impacts. Second, while they are not as affected by air pollution, drinking water contamination is a factor. So policies that bolster safe drinking water could be winners.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, clean energy policies could usher in a “Green New Deal” for rural America that boosts local jobs and economic development. That means jobs installing, constructing and managing renewable energy facilities, both small- and large-scale, plus related energy storage facilities. Energy retrofits of existing buildings can boost local contractor opportunities. Zero-emission vehicle technologies like battery electrics mean people can fuel their vehicles with local clean electricity instead of with the global commodity of oil. Those oil and gas purchases otherwise enrich far-off corporations and nations, representing a failure to circulate and invest that money locally. Natural and working landscapes in rural areas could also potentially receive carbon offset funding to be preserved as carbon sinks.

It would be a winning climate recipe that could also have the benefit of addressing the extreme inequality in the country. The politics, economy and global climate could all come out ahead with a Green New Deal.

Some heartening recent progress on the EV front, first on consumer demand and automaker supply and second on fast-charging technology:

Some heartening recent progress on the EV front, first on consumer demand and automaker supply and second on fast-charging technology:

- Tesla reported Model 3 third quarter sales of 56,000. They averaged production of 4,300 Model 3s a week, and in the final week of the quarter the company produced 5,300. Perhaps more significantly, the Model 3 had the highest revenue of any car model in the United States, beating out the Toyota Camry and the Honda Accord, which ranked it fifth among all car models sold.

- Major battery maker LG Chem just announced an investment in Enevate, a company that is developing a lithium-ion battery charging technology that could allow EVs to charge at close to the speed of filling up a gas tank. Batteries can get up to 75 percent of their full capacity in just five minutes. With a 200+ mile battery, that means drivers can get 150 miles range in a few minutes.

With lots of gloomy environmental policy news out there, it’s nice to see progress continuing on this crucial clean technology.

People who don’t like infill development cite electric vehicles as an excuse to continue to sprawl. People who don’t like cars like to point out the environmental limitations of electric vehicles.

People who don’t like infill development cite electric vehicles as an excuse to continue to sprawl. People who don’t like cars like to point out the environmental limitations of electric vehicles.

And so we have a simmering tension, recently manifested in Alissa Walker’s otherwise engaging Curbed piece “When Electric Isn’t Good Enough” on the need to reduce vehicle miles traveled and reliance on single-occupancy vehicles — even if they’re electrically powered.

Reducing driving and building more walkable, bikeable and transit-friendly neighborhoods are obviously imperatives. Environmentally, we need the reduced emissions and more compact buildings that use less energy and water. Health-wise we need the exercise and social interaction. And economically, we need the savings on housing, transportation and utility bills. Walker’s piece helps makes that case.

But electric vehicles are still a crucial technology. Driving will continue regardless of development patterns, and we must decarbonize it. We should think of it as a “loading order” (to borrow an energy phrase for prioritizing efficiency over new electricity generation): first we try to reduce driving miles, then we decarbonize all remaining driving. Walker’s article is helpful in emphasizing the need for action on the first priority.

But missing from the article is mention of the crucial co-benefits of vehicle electrification. The battery revolution propelled by EV purchases means cheap energy storage to balance intermittent renewables like solar and wind power on our grid, which helps to decarbonize our electricity sector. Cheap batteries also mean we can now have battery-powered transit buses, not to mention e-bikes and e-scooters — some of the emission-reducing technologies hailed in Walker’s piece.

Overall, the article is a helpful reminder that we need to build better neighborhoods and encourage efficient modes of transportation. But we shouldn’t downplay the significance of electric vehicles as a crucial clean technology. In short, EVs are a necessary — but not sufficient — climate-fighting technology.

It may not be the snazziest-looking electric vehicle ever made, but the now-discontinued Chevy Spark EV could pack a punch. As E&E News related in their recent piece on Palo Alto EVs [pay-walled]:

It may not be the snazziest-looking electric vehicle ever made, but the now-discontinued Chevy Spark EV could pack a punch. As E&E News related in their recent piece on Palo Alto EVs [pay-walled]:

[Ben Kaupp, sales manager of Boardwalk Chevrolet in Palo Alto] owns a dozen cars and loves speed. One of the fastest he’s ever had is the Chevy Spark, a wedge-shaped little electric hatchback that, “before they figured out that they really shouldn’t give them that much power,” could out-accelerate the 600-horsepower Corvette Z06, one of the fastest production cars GM has ever made.

Pretty impressive for a car that looks like the stunted child of a Fiat and a shopping cart. But like other unfortunate-looking early EVs (the Nissan LEAF being another), the electric drive performance is superb.

Of all the EV automakers, only Tesla figured out early that the vehicles needed to be sold based on performance and technology. With just a bit more styling, a car like the Chevy Spark EV could have been a contender.

As governments around the world seek to encourage more adoption of zero-emission vehicles like EVs, their leaders often need help determining the most effective policies to encourage demand and lower costs. And now we have some analysis of the efficacy of various approaches.

As governments around the world seek to encourage more adoption of zero-emission vehicles like EVs, their leaders often need help determining the most effective policies to encourage demand and lower costs. And now we have some analysis of the efficacy of various approaches.

The National Association of State Energy Officials (NASEO) has developed, along with Cadmus, a tool for states and localities to assess EV policies and offer regulations that encourage effective growth of both EV charging infrastructure and adoption. Utility Dive reported on the most effective policy:

By far, the rubric assigns the highest weight to vehicle purchase incentives, which could include grants, rebates or tax credits, along with exemptions from sales tax, registration and licensing fees.

Infrastructure is important, too, but not as much as consumer financial incentives. And surprisingly, fleet purchases and other demonstrations aren’t as effective as simply communicating some of the basics around EVs to a population largely unaware of EV technology and its benefits.

Incentives alone are probably not enough to encourage widespread deployment, but if a policy maker had to choose just one…

In my Berkeley Law research on electric vehicles (such as our recent 100% Zero report), I’ve heard repeatedly from EV experts that auto dealer unwillingness to sell and market the vehicles is a significant barrier to deployment.

In my Berkeley Law research on electric vehicles (such as our recent 100% Zero report), I’ve heard repeatedly from EV experts that auto dealer unwillingness to sell and market the vehicles is a significant barrier to deployment.

And the numbers suggest why that might be the case. As E&E News reported [pay-walled] in a recent article on Palo Alto EVs:

The average dealer in the U.S. grossed about $1.75 million in profits last year from selling new cars, according to the National Automobile Dealers Association. Those profits are generally declining. That same dealer made about $3.3 million on service and parts, a figure that has been rising. In other words, dealers are making less and less money selling cars, and more and more from maintaining them.

So why should car dealers have any incentive to promote electric vehicles to customers, when they have essentially no maintenance needs and few parts to replace? As one dealer described in the article, EVs require about as much care as a toaster. Dealers have otherwise grown accustomed to generous returns from maintenance contracts on repair-intensive internal combustion engine vehicles.

The cost data described above help explain why an EV-focused company like Tesla foregoes the traditional dealer model in favor of direct sales. Until we solve the dealer problem, it’s likely to remain a bottleneck in getting this critical zero-emission technology out to the general public.

As the saying goes, the future is already here, it’s just not widely distributed yet. And when it comes to electric vehicle adoption, infrastructure, and consumer awareness, Palo Alto takes the cake.

As the saying goes, the future is already here, it’s just not widely distributed yet. And when it comes to electric vehicle adoption, infrastructure, and consumer awareness, Palo Alto takes the cake.

As E&E News reported [pay-walled]:

In this city of 67,000, one of the wealthiest in wealthy Silicon Valley, 30 percent of all new cars purchased last year were electric vehicles, according to data from the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT). That’s the highest adoption rate in California, which is home to half of the nation’s EVs. Per capita, Palo Alto is America’s electric car capital.

The affluent community is the home of Stanford and birthplace and bedroom of many major tech companies. Partly as a result of its tech-savvy nature and solidarity with local tech entrepreneur and Tesla CEO Elon Musk, its residents are all in on EVs.

Notably, the city has a tremendous build-out of chargers, particularly at workplaces. Many of the major tech companies have hundreds if not thousands of chargepoints on their campuses.

While not every city in America has the wealth to purchase these sometimes-expensive vehicles and to install all those chargers, as prices continue their steep decline for both infrastructure and vehicles, more of the world will start to look like Palo Alto — at least in terms of its zero-emission vehicle deployment.

I’ll discuss other aspects of EV deployment from this E&E article in two subsequent blog posts.