It might seem obvious that phasing out oil and gas production in California would benefit the climate. But the reality is much more complicated, in terms of emissions, economics and even geopolitics.

CLEE just released the report Legal Grounds with policy options to reduce in-state production, but the question of how much a phase out would benefit the climate was mostly beyond the scope of our analysis (which we’ll be discussing in more detail on a free webinar on Tuesday, May 12th, at 11am). However, it’s a question worth examining in more detail.

The challenge is that demand for fossil fuels in the state will remain for the foreseeable future, even if local production ceases. If we stop producing oil here, we’ll start importing more from elsewhere.

While California’s oil demand is already decreasing due to market and policy factors, until consumers completely transition to zero-emission vehicles and find alternatives to petroleum-based products like plastic and asphalt — and until refineries in the state stop exporting to markets around the Pacific — the supply will still find its way to the state. If that oil comes from out-of-state sources, the carbon footprint may even be higher than if California produced it domestically due to shipping emissions.

However, economic theory indicates that a decrease in California production will mean some decrease in consumption, as global prices will rise slightly from reduced overall supply. One study indicated it could lead to global emission reductions of 8 to 24 million tons of CO2 per year. And any oil left in the ground is oil not burned in the long run, meeting one of the highest priorities of climate activists. So a California phase-out could help avoid some emissions, though the rate is unclear.

What about the political implications of phasing out oil and gas consumption for climate policy? One argument is that a phase-out here might inspire other jurisdictions to follow suit. As most climate models indicate that some percentage of fossil fuels will have to remain untapped as an imperative for avoiding the worst of climate change, why not start in California, a state committed to climate action? It might be hard to imagine that top oil-producing countries like Saudi Arabia, Iraq and Iran (or other U.S. states) would be so inspired, but perhaps places like Norway or Colorado might be more politically open to it. And if the oil industry in California phased out, its lobbying power might also wane, allowing the state to pursue more aggressive policies on the demand side.

The economic impacts of a phase-out for climate policy are also complicated. As Severin Borenstein at UC Berkeley Energy Institute at Haas blogged in 2018, a phase-out in California would mean slightly higher worldwide oil prices, which would in turn enrich the major oil producing companies and countries who are still providing supply. As he summarized:

One could think of this as similar to a very small worldwide carbon tax, except in this case the revenue is not rebated to the population as a whole or used to reduce other taxes, but rather handed to those who own and control the world’s oil production

But there is one clear benefit from phasing out in-state oil and gas production in California: improved health and safety of surrounding communities. Scientists have linked drilling for oil and gas to numerous public health challenges, including increased rates of asthma, cancer, and other health threats. And much of the drilling in California occurs in or near residents of disadvantaged communities, adding to the urgency.

Another certainty is that California is firmly committed to reducing demand for fossil fuels, through boosting zero-emission vehicles, requiring lower-carbon fuels, and pricing carbon through cap and trade. As this activity increases, it will put pressure for corresponding reductions on the supply side, regardless of any other uncertainties involved.

So while the benefits of a phase-out of California production may be somewhat unclear in terms of avoided carbon emissions, the health and safety value is clear. California’s ability to manage the process with a careful, just transition could demonstrate a viable path forward for this long-term climate effort.

Note: This article was co-authored with Fan Dai, Aimee Barnes (California-China Climate Institute, University of California, Berkeley [CCCI]), Yunshi Wang (University of California, Davis) and Angela Luh (University of California, Berkeley) and cross-posted at CCCI. In addition, Mary Nichols and Candace Vahlsing (California Air Resources Board); Patty Monahan and Ben De Alba (California Energy Commission); Lauren Sanchez (California Environmental Protection Agency); Prof. Ouyang Minggao and Prof. Wang Hewu (Tsinghua University); Gong Huiming (Energy Foundation China) and Evan Westrup (California-China Climate Institute) contributed to this piece.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to sweep across the globe, now is the time for us to reflect not only on our shared vulnerability, but also on what’s possible through collective action. California and China, which have both confronted this virus with great force, are also uniquely positioned to tackle the climate crisis head-on – together. One of the most effective steps we can take is to get more zero-emission vehicles on our roads.

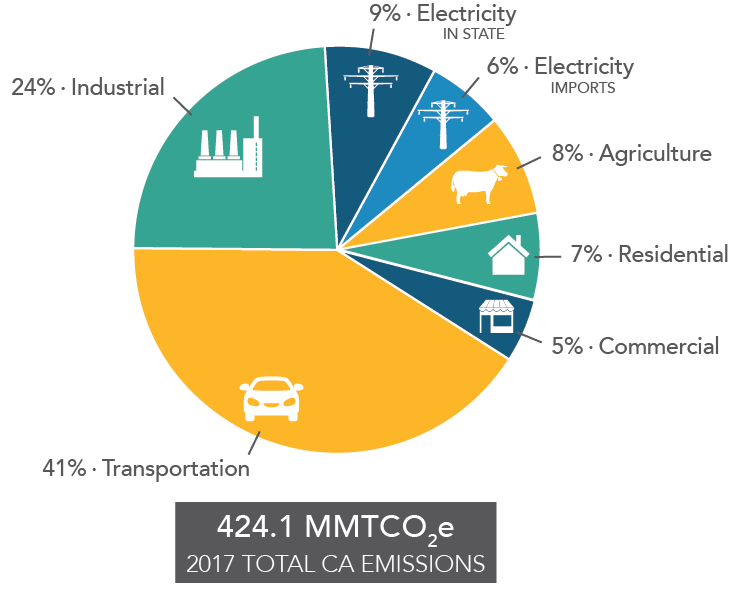

Why focus on transportation? The answer is simple: it’s one of the greatest sources of carbon emissions and major sources of air pollution. In China, analysts estimate that transportation emissions constitute more than 9 percent of the country’s overall carbon footprint – and that share is expanding rapidly. In cities, for example, transportation accounts for as much as 65 percent of carbon emissions in Shenzhen, and vehicle emissions are responsible for 45 percent of the total particulate matter concentrations in Beijing. Meanwhile in California, 41 percent of overall emissions come from transportation, due mostly to passenger vehicles. The share rises to nearly 50 percent when carbon emissions from producing gasoline and diesel are factored in. Notably, transportation emissions have continued to increase in California, while emissions in nearly every other sector have declined steadily in recent years.

The good news is that we know what we need to do – and California and China have set world-leading zero-emission vehicle goals to get us there. In China, the goal is for zero-emission vehicles to account for 25 percent of total vehicle sales by 2025, increasing to 40-50 percent of total sales by 2030. Meanwhile, California aims to have 1.5 million zero-emission vehicles on the road by 2025 and 5 million by 2030. California also established a voluntary framework with five vehicle manufactures to reduce emissions that can serve as a path forward – alternative to the one which the federal government has now chosen – for clean vehicle standards nationwide. To help achieve these goals, both California and China have offered numerous incentives to consumers and manufacturers and aggressively invested in research and development.

As a result, in part, of these policies, California and China are dominating the global zero-emission vehicle market and have put a significant share of these vehicles on our roads. In fact, China, the number one market in the world for plug-in electric vehicles, accounted for 54 percent of the world’s 2.26 million vehicles sold last year. And by the end of 2019, 3.8 million plug-in vehicles were on China’s roads. Similarly, California accounted for nearly half of America’s plug-in vehicle sales in 2019 with 156,101 vehicles sold and approximately 700,000 vehicles on the state’s roads.

While these figures are encouraging, the road ahead is long and winding. In 2019, plug-in vehicles represented just 8.26 percent of California’s annual new vehicle sales and overall sales of these vehicles declined year-over-year by 12 percent. And after years of zero-emission vehicle sales growth, China saw a similar trend in 2019, recording a 4 percent decline in sales year-over-year. In China, experts attribute this drop primarily to demand-side subsidy cuts and in California, the expiration of federal tax credits for purchases from many of the major manufacturers was a contributing factor.

So where do we go from here? What can California and China do to reverse recent trends and encourage much faster adoption of zero-emission vehicles? We start by accelerating our cooperation. This means taking steps to align California and China’s zero-emission vehicle goals, policies, research and investment. Possible actions include:

- Internal Combustion Engines: Studying options to phase out the sale of vehicles with internal combustion engines by a specific date.

- Zero-Emission Vehicle Goals: Harmonizing zero-emission vehicle goals for 2030 – and beyond, with shared targets for new vehicles sales (as the ZEV Alliance has done) and/or zero-emission vehicle market share.

- Charging Infrastructure: Agreeing to mutual charging infrastructure targets, while also expanding and sharing research on market opportunities and technological innovation, from the battery to the charger.

- Procurement: Accelerating and aligning procurement requirements – in both the public and private sectors.

- Credit-Based Requirements: Encouraging China to adopt and adapt California’s credit-based zero-emission vehicle mandate, which requires auto manufacturers to produce a specific number of zero-emission vehicles each year, based on the total number of vehicles sold by the manufacturer in the state.

- Market Demand: Collaborating on innovative ways to drive zero-emission vehicle market demand, including sharing best practices, expanding public-private-nonprofit partnerships (e.g. Veloz, Go Ultra Low models) and supporting demonstration projects to deploy hydrogen fuel cell technologies.

- Innovation and Investment: Allowing and encouraging both zero-emission heavy-duty and passenger vehicle manufacturers to compete in California and Chinese markets, while continuing to expand government and business-to-business investment, loans and grants focused on research and development of new technologies, as well as workforce development.

Current geopolitical tensions and the COVID-19 crisis complicate this partnership between California and China, but this uncertainty should remind us that we have no time to waste. The University of California-wide California-China Climate Institute, working in partnership with the Institute of Climate Change and Sustainable Development at Tsinghua University, stands ready to drive this collaboration forward. And as California and China work ever more closely together, we have to bring in other players like the European Union, United Kingdom, Canada and Mexico. All of this, with the goal of getting more zero-emission vehicles on the road before the next United Nations climate talks. By doing this, we send a clear message to the world: zero-emission vehicles are the future.

California (and the nation as a whole) is getting worse in our efforts to reduce emissions from transportation (i.e. driving). Last week, I gave a talk in the UC Berkeley Institute of Transportation Studies lecture series on what we can do about it. You can view the recording here:

In brief, we’re failing because driving miles are up while transit usage is down, in part due to poor land use policies that pushing housing farther from jobs. We need to encourage housing near transit and encourage electric vehicle usage for all other driving.

And on the subject of how we’re failing to build enough housing near transit, you can view a recording of a January 30th symposium at UC Hastings School of Law on this topic, featuring two panel discussions (I spoke on the second) and a closing keynote from State Senator Scott Wiener. You can also read a summary of the symposium from Hastings student Leigha Beckman, who helped organize the event.

Happy viewing!

I began working on climate change law and policy on January 20, 2009, the day I joined Berkeley Law, which was coincidentally Barack Obama’s Inauguration Day. So it’s been a full decade for me focusing exclusively on this subject (I focused on related land use and transit issues prior to 2009), roughly coinciding with the 2010s now coming to a close.

As we mark the end of this decade, two things stand out: remarkable progress reducing the price and deploying critical clean technologies, and dispiriting failure to reduce overall greenhouse gas emissions, with more severe climate impacts happening each year.

I noted some of these trends in a foreword to “Climate Change Law in the Asia Pacific” from Berkeley Law, which features articles from scholars in places like Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, as well as California.

To summarize the good news on clean technology:

- From 2009 to 2017, the levelized costs for utility-scale solar photovoltaic dropped 86 percent;

- Wind power levelized costs dropped 67 percent from 2009-2017; and

- Lithium ion battery prices (central to electric vehicles and grid energy storage) have dropped 85 percent from 2010 to 2018.

This progress is the key reason for optimism on climate change. With the price decreases, support for deployment has increased across the political spectrum and allowed for some remarkable success stories on emissions reductions, such as California’s ability to achieve its 2020 carbon goals four years earlier, due primarily to renewable energy deployment.

But despite the progress, we have this sobering data:

- Carbon parts per million have increased from 385 in 2009 to 411 (and counting).

And unsurprisingly, the bill is now coming due. This decade has brought some of the predicted severe climate impacts, such as unprecedented wildfires, droughts, extreme rain events and hurricanes, and warming oceans.

On the positive side, the extreme weather has helped shift public opinion in favor of climate action. But it’s come at a significant cost to human life, happiness, and ecosystems.

Hopefully in the 2020s we’ll see the widespread deployment of clean technologies and other climate-smart practices that we need to stabilize and reduce emissions. And while climate impacts will inevitably worsen, perhaps our ability to withstand them will improve, such as through electricity grid resilience in the face of wildfires and using natural infrastructure to lessen storm surges and flooding.

And to make any of these positives happen, we will need smart policies and public support and political leaders to enact them. I’ve had the good fortune to work on climate policy now for over a decade, and as the 2020s dawn, much work remains.

UC Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) is today releasing a new report on lessons learned to advance electric vehicle (EV) deployment in France and California. Electric Vehicles and Global Urban Adoption: Policy Solutions from France and California is based on a June 2019 international conference at UC Berkeley, co-sponsored by CentraleSupélec and Florence School of Regulation (FSR) in France, featuring speakers from California and French utilities, energy regulators and industry.

Electric vehicles are important to both California and France because transportation accounts for approximately 20 percent of emissions in Europe, 30 percent in the United States, and 40 percent in California (and even more when factoring in emissions from oil refineries). Yet electric vehicles still represent a small share of the overall vehicle market worldwide, at under 10 percent of new car sales in California and under 2 percent in France, despite aggressive policy targets.

Deployment in California and France is more perhaps more complicated than other jurisdictions, given that approximately 40 percent of residents in both places live in multi-unit dwellings, such as apartments, townhouses, and condominiums. Many of these dwellings are in urban areas with little or no access to charging, given the lack of dedicated parking spots and lower vehicle ownership rates. French law requires builders of new apartment buildings to install chargers, but residents of existing buildings don’t receive those benefits.

As leaders in California and France seek to boost EV adoption, speakers at the conference identified the following challenges, also summarized in the report:

- Lack of access to affordable, convenient private electric vehicles;

- Complexity and cost of installing charging in urban settings and existing multifamily buildings;

- Declining federal incentives and insufficient vehicle demand;

- Electricity rate design decreases the financial viability of charging stations;

- Difficulty of adopting optimal charging practices that could benefit users and electric utilities;

- Difficulty of adopting optimal charging practices that could benefit users and electric utilities; and

- Need for grid infrastructure upgrades to avoid high costs on first-movers.

The conference speakers also discussed priority solutions, as the report details, including:

- National and state governments could require owners of existing multifamily buildings to install charging stations;

- National and state governments could assist transportation network companies (TNCs) like Uber and Lyft in encouraging electric vehicle adoption among their drivers, through support for the deployment of fast-charging hubs, driver education programs, and new pilot projects; and

- Electric utilities and regulators could develop new rate designs to incentivize charging while optimizing grid efficiency.

These and other solutions are discussed in the report, which will hopefully help stakeholders in both jurisdictions achieve an electric future for transportation. Bonne route!

On this morning’s 10am edition of Your Call’s One Planet Series, we’ll discuss electric vehicles (EVs), a critical clean technology for addressing climate change — but one that has yet to see mass adoption.

What progress is being made on EVs? What challenges remain? What can be done for people who don’t have a dedicated parking spot for charging access? How clean and sustainable is the battery supply chain and disposal process?

Joining me to discuss these questions and more will be:

- David Reichmuth, senior engineer in the Clean Vehicles program at the Union of Concerned Scientists. Dr. Reichmuth has testified at hearings before the US House of Representatives, the California State Legislature, and the California Air Resources Board, and he is an expert on California’s Zero Emission Vehicles regulation.

- Max Baumhefner, Senior Attorney with the Climate and Clean Energy Program at NRDC, based in San Francisco. He focuses on electrifying the transportation sector in a manner that also accelerates the transition to a smarter, more affordable electric grid powered by renewable resources.

You can stream it live at 10am today or listen to 91.7 FM in the San Francisco Bay Area. Call 866-798-TALK with questions or comments!

One of the great things about electric vehicles is that their simple design (battery+motor, with no engine or transmission) means very little maintenance costs, as well as potentially very cheap models in the years to come, as battery prices (the main cost element of the vehicles) continue to decrease over time.

But that simpler construction also means the auto industry will undergo significant changes, resulting in many jobs eliminated. To be sure, new jobs in battery manufacturing, repair, reuse and recycling will be created, along with electronics manufacturing and infrastructure deployment (to offset gas station jobs losses). But the phase out of engines will be significant. As E&E News reported [paywall]:

There is no hiding from the dark clouds on the horizon of U.S. automobile engine and drive assembly parts manufacturers. They number more than 1,100 firms with 130,000 employees and $8 billion in annual payrolls. The greatest concentration of them are in Ohio, Indiana and Michigan, Rust Belt states where industrial manufacturers, their workers, and the workers’ communities have been repeatedly pounded by “creative destruction.”

To put a finer point on these numbers, the article describes how internal combustion engines require 107 forgings to manufacture, while a Tesla Model S or a Nissan LEAF without any engine at all requires just 7 or 8 forgings. So adios to most forging jobs.

To be sure, these job transitions are no reason to pump the brakes (ahem) on policies to encourage electric vehicle deployment. As mentioned, EVs will help create many new jobs, and consumers will spend their savings on maintenance on other industries, using the newly available cash to purchase other things and create new jobs. So on balance, EVs should be a net positive for the economy (not to mention a slam dunk on the environment and public health).

But policy makers will need to consider options to minimize these job losses and work with affected employees on retraining programs. They will also need to think through the impact of these job transitions on our country’s electoral politics. We want to avoid what we’ve seen with the electricity sector, with “coal state” politics in the U.S. Senate and presidential races slowing the transition to renewable energy.

I hope the transition to zero-emission vehicles happens soon enough that this becomes an urgent problem we have to tackle — and solve — quickly.

Most trucks on the road today are slow and smelly, causing a majority of the harmful air pollution in urban skies and contributing to our greenhouse gas emission problem. But technology is offering promising solutions to make these trucks zero emission — will they be fueled by battery electric power or hydrogen fuel cells?

Jim Park in Trucking Info lays out the situation with this competition over fuels and technology, and it seems to me that battery power is gaining rapidly. On the hydrogen side, we currently have three main trucking companies: Nikola, Kenworth/Toyota, and a Canadian consortium collaborating on AZETEC (Alberta Zero-Emissions Truck Electrification Collaboration). The battery electric truck side is led right now by Daimler and Tesla.

Hydrogen has two clear advantages over batteries: long-distance range (500-800 miles) with a light payload for the fuel and fuel cell, weighing no more than a typical diesel sleeper tractor. These trucks can also refuel quickly.

But batteries are getting cheaper and more powerful. Electric trucks generally benefit from stop-and-go operations with more opportunities for regenerative braking and high-powered charging. Companies like Daimler are responding to this large part of the market:

“We found that probably 80% of the group we spoke to were not running more than 150 miles per day,” says Andreas Juretzka, head of Daimler’s e-Mobility Group. “That led us to a battery spec of 230-mile range, which covers, among other things, the swings in ambient temperature that can affect battery performance and to alleviate the customers’ range anxiety.”

Tesla has meanwhile announced a 500-mile range truck with zero-to-60 times of less than 5 seconds — sure to be of interest for driving quality alone.

Both types of zero-emission trucks will require a whole new build-out of charging infrastructure though, including fast-charger stations for batteries and hydrogen stations for fuel cells.

This competition over fueling technology is probably good news for consumers and all who live near and drive behind these trucks. But at the same time some clarity on which technologies are suitable for which applications will be needed soon, as policy makers are right now contemplating public investments in the various fueling infrastructure needs. They don’t want to invest in permanent infrastructure for the wrong type of vehicle.

My guess? Battery electrics will dominate for 80% of the trucking market, but hydrogen will still be useful for longer-distance trucking. But either way, the benefits for air quality and our carbon footprint will be immense.

On the list of things that people may have to sacrifice to combat climate change and reduce their personal carbon footprint, flying is an unpopular sell for many. Indeed, it was at the root of much conservative criticism of the initial Green New Deal, with claims that the plan would lead to prohibitions on flying.

But aviation emissions are substantial: commercial flights currently constitute 2% of global carbon dioxide emissions, per the International Council on Clean Transportation.

Fortunately, battery technology improvements may soon make flying a low-carbon activities, and even zero-emission depending on the electricity source. While electrification of passenger vehicles, scooters, bikes, and even trucks is rapidly progressing, electric airplanes are admittedly still in their infancy. Most have short ranges (under 80 miles), but they boast the same advantages of other electrified transport: fast acceleration, quiet flights, and dramatic fuel savings, given that electricity is cheaper than petroleum fuel.

Yet new companies are boasting substantial improvements to come. For example, as E&E News reported recently [paywalled], Israeli startup Eviation Aircraft announced that “Alice,” its first all-electric plane, will take flight in 2022. The planes can carry nine passengers up to 650 miles, albeit at a hefty price tag. And hybrid options may be available even sooner.

If the trajectory of e-planes follows other transport technologies, we should have cheaper, longer-range electric planes available in the coming decades for the bulk of flights. To be sure, we still should find ways to reduce the need to travel and build out a high speed rail network, particularly to replace expensive and polluting short-haul flights. Low-carbon biofuels can also be an interim solution.

But in the long run, technology improvements with e-planes could provide an important low-carbon option to allow people (who can afford it) the ability to keep flying to destinations, without the same risk of damaging the climate. To win over critics and more political support for climate action, we’ll certainly need this option to take off.

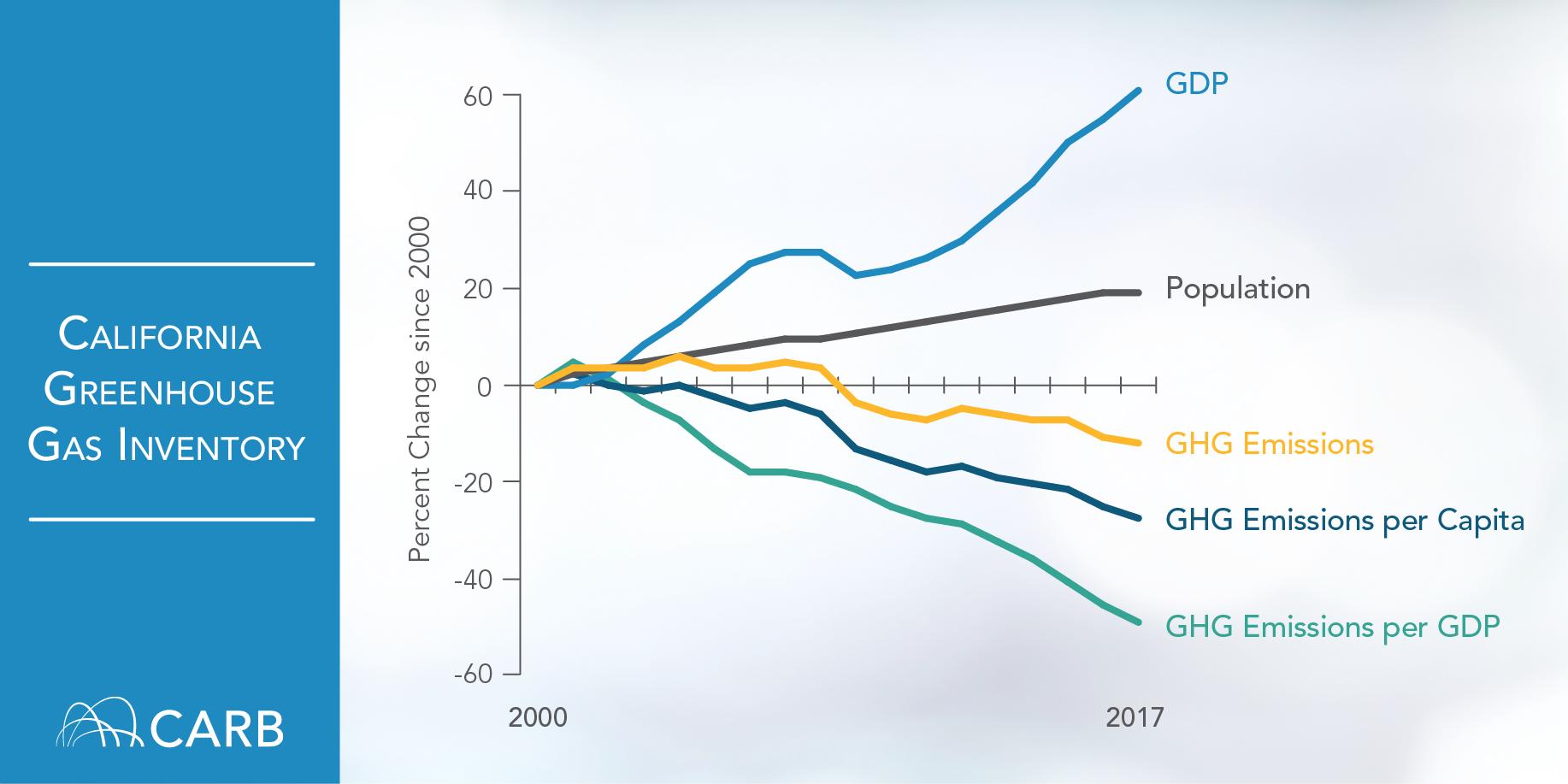

Good news on California’s efforts to fight climate change: in-state emissions in 2017 (the latest available data) were down over 2016 and ahead of the state’s mandatory 2020 goals. The California Air Resources Board announced the progress yesterday, with this chart showing emissions in context of population and GDP:

Overall, emissions totaled 424 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2017, down 5 million metric tons from 2016. For reference, the 2020 reduction target is 431 million metric tons.

Most of the progress came from the electricity sector, where for the first time renewable sources made up a larger percentage of the generation than fossil fuels.

However, transportation emissions increased 0.7% in 2017, compared to a 2% increase in 2016, mostly from passenger vehicles. That total is even worse when you consider pollution from oil and gas refineries that make the fuel for these passenger vehicles. Together with hydrogen production, these sources constituted one-third of the state’s total industrial pollution.

Here’s the latest pie chart on where the emissions came from in 2017:

While the story is overall positive for California’s climate efforts, the state will have to redouble its efforts to reduce driving miles by allowing more homes to be built near jobs and transit, while transitioning the remaining driving miles to zero-emission technologies like electric vehicles.