President Biden yesterday unveiled his “infrastructure” plan, but it’s really his best and greatest shot to address climate change. I’ll be speaking about the plan and what it means for the climate at 10:20am PT on KQED’s Forum. You can also hear my thoughts on the electric vehicle charging aspect of the plan on yesterday’s NPR Marketplace.

The proposal calls for transformational investments in rail, bridges, and road repair, along with a decarbonized electricity grid, incentives for electric vehicles, an end to fossil fuel subsidies, and home energy retrofits, among other goals. The plan even seeks to end single-family zoning.

Tune in this morning to hear more!

Electric vehicle critics have directed a lot of misinformation at EV batteries, in an effort to make the (dishonest) case that they’re just as bad as gas engines. But not only are EVs far less polluting than internal combustion engines, the United States has a strong economic and environmental interest in bolstering a domestic supply chain.

My new op-ed in The Hill has recommendations on steps that federal and state leaders should take to seize the opportunity. At stake are not only a lot of potential jobs, but also a more reliable and sustainable supply of the batteries that will soon be powering most of our transportation needs.

And for more about the EV battery supply chain, check out a recent talk I gave on this subject for Berkeley Lab’s Lithium Resource Research and Innovation Center:

One of the concerns often raised about electric vehicles is the risk of battery fires. Lithium ion batteries can certainly catch fire on occasion. But how much should consumers take into account this risk when buying electric vehicles, particularly given that internal combustion engine alternatives also catch fire?

Turns out, not too much.

According to the research, the fire risk in an EV is no greater than the fire risk in a gas-powered car. For example, a U.S. Department of Transportation-funded study found that EVs are “somewhat comparable or perhaps slightly less” prone to fires compared with gas-powered cars.

Industry data bear this out, in an encouraging fashion. Tesla, the leading EV manufacturer in the US, claims that internal combustion engines are roughly 11 times more likely to catch fire than one of their EVs. And the data seem to support their claim: Teslas have to date registered roughly five fires for every billion miles driven, compared to a rate of 55 fires per billion miles traveled for gasoline cars. And more generally, lithium-ion battery cells fail at a rate of only 1 in every 12 million.

So the bottom line is that vehicles of all types are vulnerable to fires, and that risk is potentially much less in an electric vehicle, or at the very least just comparable. It’s good news, since we need electric vehicles to reduce transportation emissions and fight climate change. The main challenge going forward is preparing firefighters with the training they need to adapt to fighting battery fires, which burn differently than gasoline fires.

So if you’re considering buying an electric vehicle, don’t let the media smoke from a few battery fires obscure the truth. The climate is counting on it.

With the presidential election over, Joe Biden faces a U.S. Senate that still hangs in the balance. But even with a Democratic runoff sweep in Georgia next month, it will be very divided. So what will be possible for a President Biden and his administration to achieve on climate change?

Agency action, foreign policy changes, and spending can all make a difference on emissions, with any COVID stimulus and budget deals with Congress, if feasible, providing potential avenues for further climate action. Here are some ideas along those lines, broken out by key sectors of the economy.

Action on Transportation

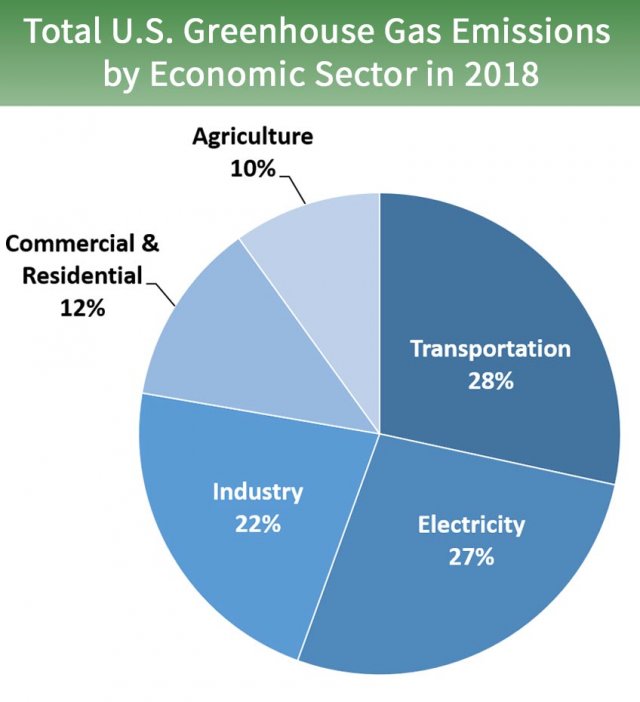

As the EPA chart above of 2018 emissions shows, transportation contributes the largest share of nationwide greenhouse gas emissions at 28%. The best way to reduce those emissions is to decrease per capita driving miles through boosting transit and the construction of housing near it, as well as switch to zero-emission vehicles, primarily battery electrics.

Transit-oriented housing is largely governed by local governments, who generally resist construction. Absent state intervention or federal legislation from a divided Congress, the Biden administration will have to make surgical regulatory changes directing more grant funds to infill housing and potentially use litigation and other enforcement tools to prevent and compensate for racially discriminatory home lending and racially exclusive local zoning and permitting practices.

On transit, a Biden administration would be very pro-rail, especially given the President-elect’s daily commuting on Amtrak in his Senate days. If the Senate flips to the Democrats, high speed rail could be a big part of any bipartisan COVID stimulus package, if it happens, which would be a lifeline to the California project that is otherwise running out of money. Other urban rail transit systems could benefit as well, and the U.S. Department of Transportation could favor and streamline grants for transit over automobile infrastructure. Notably, LA Metro CEO Phil Washington, responsible for implementing the nation’s most ambitious rail transit investment program in Los Angeles County, is chairing Biden’s transition team on transportation.

On zero-emission vehicles, Biden may have relatively strong tools to improve deployment of this critical clean technology. First, perhaps through a budget agreement with Congress, he could reinstate and extend tax credits for zero-emission vehicle purchases, which have expired for major American automakers like General Motors and Tesla. Second, he could use the enormous purchasing power of the federal government to buy zero-emission vehicle fleets. And perhaps most importantly to California, his EPA can rescind its ill-conceived attempt at a fuel economy rollback for passenger vehicles and then grant the state a waiver under the Clean Air Act to institute even more stringent state-based standards, toward Governor Newsom’s new goal of phasing out sales of new internal combustion engines by 2035.

Reducing Electricity Emissions

The electricity sectors comes in a close second place, with 27% of the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions. The move toward renewable energy, particularly solar PV and wind turbines, is so strong that even Trump had difficulty slowing it down during his single term in office, in order to favor his fossil fuel supporters. But nonetheless, the Trump administration created some strong headwinds which can now be reversed.

First and foremost, President-elect Biden can drop the tariffs on foreign solar manufacturers, which drove up prices for installation here in the United States. Second, as with the zero-emission vehicle tax credits, a budget deal with Congress could bolster the federal investment tax credit for solar, which steps down from the initial 30% toward an eventual phaseout for residential properties and 10% for commercial properties. The credit could also be extended to standalone energy storage technologies, like batteries and flywheels, if Biden budget negotiators play their hands well (easy for me to say). A Biden administration could also improve energy efficiency by dropping weak regulations on light bulbs and appliances like dishwashers at the U.S. Department of Energy and introducing more stringent ones instead.

Legislatively, any COVID stimulus deal (again, if it happens) could potentially contain money for a big renewable energy buildout, including for new transmission lines, grid upgrades, and technology deployment. In terms of regulations, if Biden is able to get any appointments through the Senate to agencies like the Federal Regulatory Energy Commission (FERC), that agency could make climate progress by simply letting states deploy more renewables and clean tech, including demand response, as well as potentially supporting state-based carbon prices (a move supported by Trump’s FERC appointee Neil Chatterjee, which promptly resulted in his demotion last week).

Slowing Fossil Fuel Production

The two big moves for the Biden administration will be to stop new leases for oil and gas production on public lands (including immediately restoring the Bear’s Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments) and bringing back the methane regulations on oil and gas producers that the Trump administration rolled back. As a bonus, his Interior Department could engage in smart planning to deploy more renewable energy on public lands, where appropriate, including offshore wind.

Other Climate Action

The list goes on for how the Biden administration can embed smart climate policy into all agencies and facets of government, with or without Congress. Of particular note, his appointees at financial agencies like the Federal Reserve and U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission could bolster and require climate risk disclosures for institutional and private investors. The U.S. Office of Management and Budget could ramp back up, based on the best science and economics, the social cost of carbon, which represents the cost in today’s dollars of the harm of emitting a ton of carbon dioxide equivalent gas into the atmosphere. This measure provides much of the economic justification for the federal government’s climate regulations. And of course, President-elect Biden can have the U.S. rejoin the 2015 Paris climate agreement immediately upon being sworn in (though the country will need to set a new national target).

Overall, Biden’s win means the U.S. will regain some climate leadership at the highest levels, with much that can be done through congressional negotiations, agency action, and spending. However, the stalemate in the US Senate likely means that any hopes for big new climate legislation will be dashed. As a result, continued aggressive action at the state and local level, as well as among the business community, will be critical to continue to help push the technologies and practices needed into widespread, cost-effective deployment to bring down the country’s greenhouse gas footprint.

One election certainly won’t solve climate change, and the costs continue to rise to address the impacts we’re already seeing from extreme weather. But given the current political climate, the actions described above could allow the U.S. to still make meaningful progress to reduce emissions over the next four years and beyond, even in an era of divided government.

Governor Newsom made a major announcement this week, issuing an executive order that California would ban the sale of new internal combustion engine passenger vehicles by 2035, and medium and heavy-duty vehicles by 2045. I’ll discuss the order and its implications this morning at 9am on KQED radio’s Forum.

We released a report at Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) on this very subject in 2018, called 100% Zero. The bottom line: this is a major new announcement that is necessary to tackle climate change and should be economically and technically feasible, assuming the state takes additional implementation steps discussed in the report.

However, whether it’s legally feasible for California to implement this order will almost inevitably revolve around this or future presidential elections, as well as the composition of the United States Supreme Court.

Tune in today for more details!

On January 27, 2017, just one week after Trump’s inauguration, UC Berkeley Law’s Henderson Center for Social Justice held a daylong “Counter Inauguration,” featuring various panels in reaction to Trump’s victory. I spoke on an afternoon panel that day entitled “Monitoring the Environmental, Social and Governance Impacts of Business in the Trump Era” and offered my predictions on what the Trump years would bring for environmental law and policy.

I recently reviewed these predictions, three months out from the upcoming November election, to see how they measured up against the reality of Trump’s near-complete term in office. Bottom line: these predictions mostly tracked with what happened with Trump and his administration’s leaders, albeit with some steps I missed, some that never came to pass, and some positive outcomes for environmental protection.

First, I predicted the Trump Administration would follow through on the campaign pledges to boost fossil fuels in the following ways:

- Opening up public lands for more oil and gas extraction

- Slashing regulations that limit extraction and related pollution, such as the Clean Power Plan and methane rules

- Weakening fuel economy rules for passenger vehicles

- Financing more infrastructure that could boost automobile reliance (i.e. more highways and less transit)

These were all relatively predictable actions, and they all pretty much happened as predicted. On public lands and fossil fuels, Trump rolled back National Monument protection at Utah’s Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante, as well as streamlined permitting for oil and gas projects on public lands. On environmental rules in general, here is a list of 100 environmental regulations that the administration has tried to reverse. On vehicle fuel economy standards, here’s my article on EPA’s proposed rollback. And transit funding went from 70 percent of transportation grants under Obama to 30 percent under Trump, with the rest funding highways.

Second, I predicted that his administration would try to undermine clean technologies by:

- Weakening tax credits for renewables and electric vehicles

- Undoing federal renewable fuels program

- Revoking California’s ability to regulate tailpipe emissions

- Attempting to undermine California’s sovereignty to regulate greenhouse gases through legislation

- Cutting funding for high speed rail and urban transit

- Withdrawing from Paris agreement

On these predictions, I was correct on most accounts. The administration did weaken tax credits for renewables (both by not extending them or preventing them from decreasing over time, save for a recent one-year extension on wind energy as a budget compromise) and electric vehicles (by letting them expire and threatening to veto Democratic legislation that would have extended them in a recent budget bill). His EPA did revoke California’s waiver to issue tailpipe emission standards. And he famously withdrew from the Paris agreement (to take actual effect later this year) and has tried to cancel almost $1 billion in high speed rail funding in California.

But I was incorrect that the administration would pursue legislation to preempt California’s (and other states’) sovereignty to set their own climate change targets. There was little appetite in Congress to do so, though Trump’s Justice Department did seek unsuccessfully to declare California’s cap-and-trade deal with Quebec to be unconstitutional. And his record on renewable fuels is more mixed but did deliver some gains to corn-based ethanol producers, though the environmental benefits are suspect with this type of biofuel. I also failed to predict the administration’s efforts to impose tariffs on foreign solar PV panels and wind turbines, which slowed those industries somewhat.

Finally, I predicted some possible bright spots for the environment in the Trump years, much of which did occur:

- Clean tech generally has bipartisan support in congress

- Infrastructure spending in general could be negotiated to benefit non-automobile investments

- Lawyers can stop or delay a lot of administrative action on regulations

- A shift will happen now to state and subnational action on climate, which probably needed to happen anyway

Sure enough, clean technology, particularly solar PV, wind and batteries, has continued to increase in the Trump years, though not at the same pace as under Obama due to the policy headwinds. But infrastructure spending has definitely favored automobile interests, as noted above.

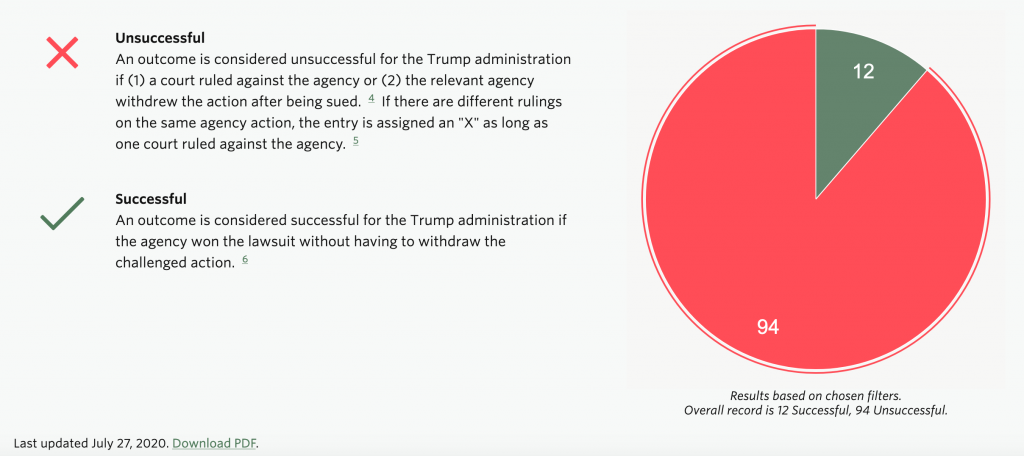

But more importantly, two critical predictions did come to pass. First, attorneys have successfully stopped most administrative rollbacks. In fact, the administration has an abysmal record defending its regulatory actions in court. As NYU Law’s Institute of Policy Integrity has documented, the administration has lost 94 cases in court and won only 12 to date, as tracked in this chart:

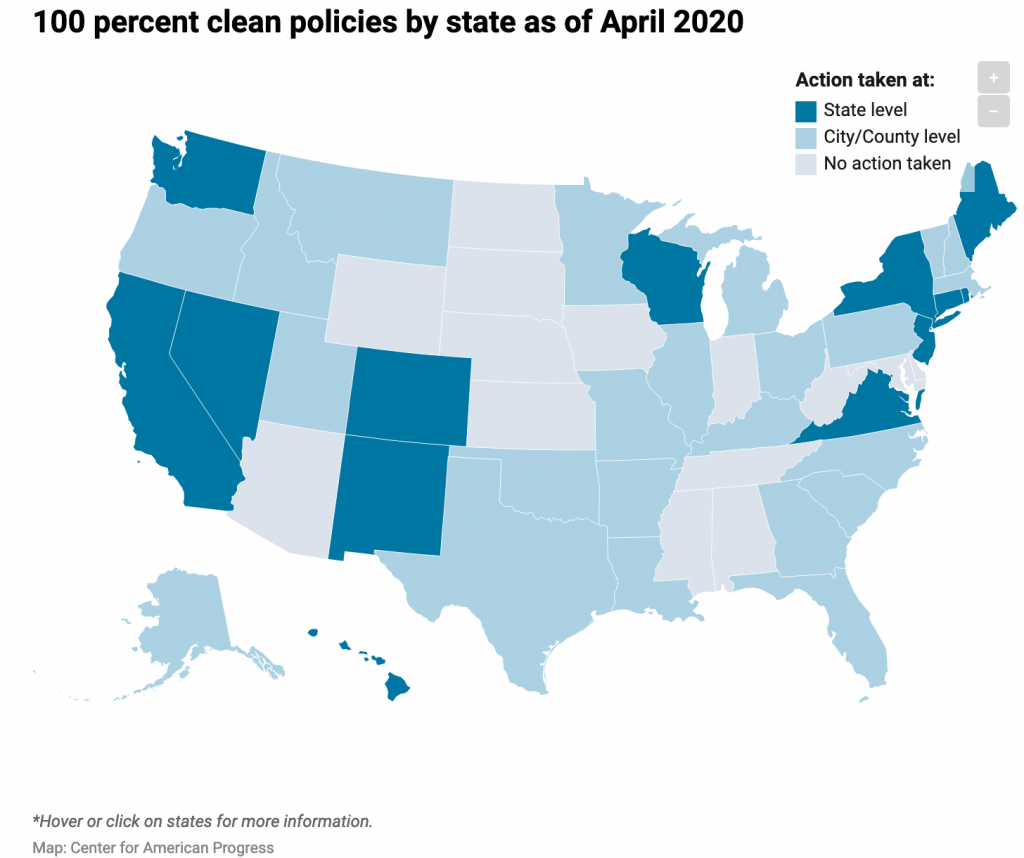

And perhaps more importantly, the lack of federal climate action has moved the spotlight to state and local governments, which often have significant sovereignty to enact aggressive policies that add up to serious national climate action. Take renewable energy, for example, per the Center for American Progress, with this map of states and municipal governments that have enacted 100% clean electricity standards:

And on clean vehicle standards, 13 states plus the District of Columbia now follow California’s aggressive zero-emission vehicle standards, representing about 30 percent of the nation’s auto market.

As a result, in many ways, environmental law and climate action appears to have survived the Trump term in office mostly intact, despite losing progress and facing some setbacks on key issues. Most of the regulatory actions can be reversed by a new administration, while Congressional action during the Trump years was relatively minimal in scope. Meanwhile, the counter-reaction to Trump spurred some significant policy wins at the state and local level.

But while one term is perhaps survivable for environmental law and climate progress, a second one could paint a completely different picture. So the stakes certainly remain high this November.

CLEE and the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) are pleased to release today the new report “Sustainable Drive, Sustainable Supply: Priorities to Improve the Electric Vehicle Battery Supply Chain.” The report identifies key challenges and solutions to ensure battery supply chain sustainability through a multi-stakeholder approach, based on our outreach to experts in the field.

The global transition from fossil fuel-powered vehicles to battery electric vehicles (EVs) will require the production of hundreds of millions of batteries. This massive deployment frequently raises questions from the general public and critics alike about the sustainability of the battery supply chain, from mining impacts to vehicle carbon emissions.

To address these questions, CLEE and NRGI are conducting a stakeholder-led research initiative focused on identifying strategies to improve sustainability and governance across the EV battery supply chain. CLEE and NRGI convened leaders from across the mining, battery manufacturing, automaker, and governance observer/advocate sectors, to develop policy and industry responses to human rights, governance, environmental, and other risks facing the supply chain.

“Sustainable Drive, Sustainable Supply” identifies the following key challenges to ensuring battery supply chain sustainability:

- Lack of coordinated action, accountability, and access to information across the supply chain hinder sustainability efforts

- Inadequate coordination and data sharing across multiple supply chain standards limit adherence

- Regulatory and logistical barriers inhibit battery life extension, reuse, and recycling

The report recommends the following priority responses that industry, government and nonprofit leaders could take to address these challenges:

- Industry leaders could strengthen mechanisms to improve data transparency and promote neutral and reliable information-sharing to level the playing field between actors across the supply chain and between governments and companies

- Industry leaders and third-party observers could ensure greater application of supply chain sustainability best practices by defining and categorizing existing standards and initiatives to develop essential criteria, facilitate comparison and equivalency, and streamline adherence for each segment of the supply chain

- Governments and industry leaders could create new incentives for supply chain actors to participate in and adhere to existing standards and initiatives, which may include sustainability labeling and certification initiatives

- Industry leaders could design batteries proactively for disassembly (enabling recycling and reuse), and industry leaders and governments could collaborate to build regional infrastructure for battery recycling and transportation and create regulatory certainty for recycling

We hope the responses to the supply chain challenges outlined in this report will provide guidance on the initial actions stakeholders can take to make this broader vision of implementation a reality, ensuring a more robust future for communities around the globe as well as for all-important electric vehicle adoption to meet climate change goals.

To learn more about this issue and the new report, join our 9am PT / Noon ET webinar today, featuring:

- Patrick Heller, Senior Visiting Fellow, Center for Law, Energy & the Environment (CLEE) & Advisor, Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI)

- Michael Maten, Automotive Public Policy, Electrification, Portfolio Planning and Strategy, General Motors

- Daniel Mulé, Senior Policy Advisor for Tax and Extractive Industries, Oxfam

- Payal Sampat, Mining Program Director, Earthworks

You can register for the webinar; read our recent FAQ on EV batteries for more information on current supply chain impacts on human rights, climate change and the local environments; and download the new report “Sustainable Drive, Sustainable Supply: Priorities to Improve the Electric Vehicle Battery Supply Chain.”

Building a low-carbon economy will rely on a transition from gasoline-powered automobiles to electric vehicles, which will require a significant increase in production of component minerals. Extracting and refining these minerals, like cobalt and lithium, can often entail challenges related to governance, human rights, and environmental quality in host countries.

To help launch a forthcoming CLEE and Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) report on this topic, join our upcoming webinar on Thursday, July 23rd, at 9am PT/noon ET/6pm CET. Panelists will discuss mechanisms to address sustainability concerns and build a better supply chain for this key emission reduction technology, as well as summarize findings from the new report.

Speakers include:

- Patrick Heller, Senior Visiting Fellow, Center for Law, Energy & the Environment (CLEE) & Advisor, Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI)

- Michael Maten, Automotive Public Policy, Electrification, Portfolio Planning and Strategy, General Motors

- Daniel Mulé, Senior Policy Advisor for Tax and Extractive Industries, Oxfam

- Payal Sampat, Mining Program Director, Earthworks

You can register here and read our recent FAQ on EV batteries for more information on current supply chain impacts on human rights, climate change and the local environments.

The Trump Administration finally released in March its long-planned rollback of federal fuel economy standards, a gift to the oil industry and its allies. However, the rollback is riddled with errors that will lead to a lengthy court battle and could be halted by a new president next January. Furthermore, long-term industry trends and international efforts to promote cleaner vehicles may make the rollback meaningless.

I detail the administration’s rule-making and the potential for more optimistic outcomes in a new opinion piece published today by the Regulatory Review at University of Pennsylvania Law School. The stakes for the climate fight, given the centrality of transportation emissions to overall greenhouse gas emissions, couldn’t be higher.

The global transition from fossil fuel-powered vehicles to battery electric vehicles (EVs) will require the production of hundreds of millions of batteries. This massive deployment frequently raises questions from the general public and critics alike about the sustainability of the battery supply chain, from mining impacts to vehicle carbon emissions.

Join me and Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy & the Environment’s Patrick Heller and Ted Lamm today at noon Pacific Time for a discussion and Q&A session on the road to a sustainable EV battery supply chain.

You can register for this free event and download our recent FAQ on EV battery supply chains. Hope you can join!