Building the mineral supply chain needed to deploy electric vehicles (including cars, buses, bicycles, and scooters) on a massive scale, if done without planning and engagement, could exacerbate environmental and social harms to communities in countries and regions where minerals are mined and processed (and, to a lesser extent, manufactured and later recycled) into usable batteries. A typical electric vehicle battery requires an array of minerals, including lithium, cobalt, and nickel, among others. Many of the locations with the richest supply of these resources are in countries or near communities with histories of governance challenges and exploitation of local and indigenous communities for resource extraction.

Governments, companies, communities, and civil society organizations face a daunting challenge: increase electric vehicle adoption and battery production, while ensuring the highest level of protection for human rights, community consent and input, and the environment.

To address this challenge, UC Berkeley Law’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment (CLEE) convened experts in December 2021 to discuss opportunities for increased advocacy and collaboration and to identify policy challenges and opportunities. Our new policy brief highlights key solutions including battery labeling standards, mining law reform, and increased technical assistance. Convening participants identified opportunities for advocates and industry leaders to improve international coordination, advocacy efforts, community engagement, and circular economy practices.

Key barriers and solutions include:

- Barrier 1: Poor supply chain governance. Policymakers lack comprehensive and targeted governance strategies to minimize harm at each stage of battery material’s lifecycle.

- Example solution: Strengthen binding measures. Enhancing binding legal and regulatory measures would support enforcement while promoting global consistency around supply chain sustainability expectations.

- Barrier 2: Lack of attention to community needs and human rights. Current mineral supply chain systems too often fail to incorporate the rights, priorities, and needs of vulnerable groups and communities impacted by mining and processing activities, as well as the transportation activities that support movement of minerals (such as additional pollution from construction and transportation vehicles, or noise from new roads).

- Example solution: Bolster technical assistance and funding. Advocacy organizations, philanthropic organizations, research institutions, and governments could allocate more resources towards supporting human rights and community priorities through funding and technical assistance.

- Barrier 3: Lack of incentives for circular economy practices and demand reduction. A lack of emphasis on circularity, and on strategies to minimize the projected demand for new battery materials while still achieving transportation decarbonization, poses a barrier to a sustainable supply chain that promotes human rights and environmental protection.

- Example solution: Set recycled content targets. Implementing targets for incorporating recycled materials into new battery cells could promote market demand for recycled materials over newly extracted materials.

For a full set of solutions and to learn more, see the policy brief here.

Cross-posted and adapted from co-author Katie Segal’s blog on Legal Planet.

On tonight’s State of the Bay, I go from host to guest, as we get into the nuts and bolts of what the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), a law that temporarily blocked admissions to UC Berkeley this year, does and how it operates. My co-host Grace Won will interview yours truly to explain how the law works in practice, as well as prospects for reform.

We’ll also learn more about Governor Newsom’s proposed gasoline rebate for Californians facing high prices at the pump. Joining us to discuss will be Alexei Koseff, reporter for Cal Matters.

Finally, we’ll hear from Marian Sousa and Marian Wynn, who are among the last of the Bay Area’s Rosie the Riveters.

What would you like to ask our guests? Post a comment here, tweet us @StateofBay, send an email to stateofthebay@kalw.org or leave a voicemail at (415) 580-0718.

Tune in tonight at 6pm PT on KALW 91.7 FM in the San Francisco Bay Area or stream live. You can also call 866-798-TALK with questions during the show.

Last week, leaders from the Biden Administration announced they would start awarding $5 billion from the bipartisan infrastructure law for a nationwide electric vehicle charging deployment.

I appeared on KTVU News in the San Francisco Bay Area to discuss this investment, which promises to be among the more consequential climate provisions that the administration has passed so far. You can watch the clip here:

I was also interviewed on NPR Marketplace about the spending, and I described why consumer perceptions about the ability to take a long road trip in an EV can loom large in purchasing decisions. You can listen here:

The administration still has another $2.5 billion to spend on EV charging from the law, and this next allotment will go to local communities, including rural and disadvantaged ones that too-often lack sufficient EV charging stations.

As 2021 draws to a close, I wanted to share some climate optimism. Climate and energy writer Dave Roberts interviewed carbon market analyst Kingsmill Bond, who is incredibly bullish on the long-term prospects for clean technology and bearish on fossil fuels.

In fact, he believes the world reached peak demand for fossil fuel, including coal and oil and gas, back in 2019, and that even as demand recovers, it won’t go beyond this peak. Meanwhile, clean technologies are plummeting in price and cost of deployment.

It’s worth reading the transcript of the full interview, but some highlights are below.

First, Bond notes that four of the crucial clean technologies (solar PV, wind, batteries, and electrolyzers to convert surplus electricity into hydrogen) are on established learning curves (the amount that their costs drop for every doubling in deployment) at between 16 and 34 percent. In practice, that means this already-cheap energy source is “a) going to get cheaper, b) going to spread globally, and then c) be followed up by these other technologies, also on learning curves, which will then provide us with the energy that we need at much lower cost.”

Second, he describes how fossil fuel incumbents are already pretty much on a death spiral. Specifically, he cites how legacy automakers were unprepared for the increasing shift toward new electric vehicles over old internal combustion engine (ICE) models:

You then look at the cost curves of the new stuff, and you realize that you’re going to have to change. You have to reallocate your capital out of ICE [internal combustion engine] cars and into electric vehicles. Meanwhile, you figure out that you’ve got continuous decline now coming for your ICE car sales, so suddenly, your ICE factory is a liability, not an asset. Furthermore, as your sales of ICE cars start to drop, you’ve got to allocate the same fixed-cost structure over a smaller number of cars, and your cost per unit increases. This is economics 101.

That’s what happens to the old people. What then happens to the new people, Tesla and BYD and the EV makers, is, as they produce more cars, the costs of the batteries fall because of these learning curves. As costs fall, demand increases, and as demand increases, they’re taking more market share, and they can then go to the second feedback loop, which is the financial markets.

Tesla can go to the financial markets and in an afternoon they can raise several billion dollars and build a new factory in Berlin, which increases their capacity to build at the same time the fossil fuel sector is finding it very difficult to raise capital, and is obliged by investors to change their strategic direction — as we saw, famously, with Engine No. 1.

The reason these incumbents struggle to adapt is relatively simple:

The answer is, incumbents, first of all, try and resist change. Then they struggle to put capital into these new technologies, because they’re not sufficiently profitable. You saw lots of examples of the oil center saying that over the last decade: we’re not going to put our money into solar and wind because we can get a 20 percent IRR on oil against a 5 percent IRR on solar. Why would we? The problem, then, is that by the time this stuff does get profitable and starts to eat into their old business, it’s too late, and other people have moved into this area. That’s exactly what’s happening now in the energy system.

Finally, Bond argues that the potential for cheap and abundant clean energy is massive: “If you look at the technical potential of solar and wind, which has been a lot in the last five years, it’s 100 times our global energy demand today.” It’s hard to imagine just how different our world would be if clean energy was essentially cheap and limitless.

Something to ponder as we head into the new year of 2022, with much work to be done to address climate change. May it be a good one for all of you!

Ryan Popple, former CEO and co-founder of electric bus company ProTerra, venture capitalist for transportation electrification, early Tesla employee, Iraq War veteran and father of three, passed away on Wednesday night at the age of 44, for reasons unknown.

I had the good fortune to meet Ryan back in 2012, when UC Berkeley and UCLA Law convened a group of experts (including Ryan) on ways that California could dramatically scale up the sale of battery electric vehicles by 2025, now just a few short years away. The resulting report, Electric Drive by ’25, presented innovative and still-relevant solutions to boosting EVs, which were then in their infancy. Ryan was a major contributor to that report.

While I’ve had the chance to work with hundreds of experts over the years in our Bank of America-supported law school convening series, Ryan immediately stood out as an all-star. At a time when many people doubted that vehicle electrification was viable, he brought clear and convincing evidence that this transition was inevitable. His thoughtfulness and insights were impressive, and I made sure to keep in touch with him afterwards (and also recommended him to friends and policy makers as a valuable resource).

I was thrilled when he helped launch ProTerra and turned that company into a major player in the electric bus space. He recently left the company to return to his venture capital roots, where he was in the midst of identifying and supporting the game-changing companies of the future.

His loss is tragic, untimely, and heart-breaking. For those who work on climate change, he leaves a big hole. Condolences to his family, friends and colleagues.

For a taste of his humor, humility, and wisdom, here’s a recording of a presentation he gave last year, which shows his astuteness at identifying broader societal and environmental trends and the companies that can address them.

Rest in peace, Ryan.

The Democrats reconciliation bill — once pegged at $3.5 trillion but now apparently $1.5 trillion due to compromises with conservative West Virginia Democrat Sen. Joe Manchin — could supercharge electric vehicle adoption dramatically in the next few years.

The bill contains a provision that would restore the $7,500 EV tax credit for all models under a certain price, with an additional $4,500 incentive for union-made EVs assembled in the United States. That’s a total incentive of $12,500 off an electric vehicle, which some experts describe as the largest consumer incentive the federal government has offered to date.

This provision comes on the heels of tremendous recent success for electric vehicle sales. Electric vehicles accounted for roughly two percent of all car sales last year, but this past summer, sales increased to nearly five percent of light-duty vehicles like SUVs and sedans and more than twenty percent of all passenger vehicles sales.

Some analysts credit the greater variety of electric models now available, including smaller crossovers like the Volkswagen ID.4. More are on the way, especially electric trucks with the Ford F-150 and Rivian.

So the future of electric vehicles looks promising, but it could be downright blistering with these new incentives.

With all the momentum, are oil executives nervous? Not according to a recent survey by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. More than half the executives who responded predicted that EVs will make up less than a fifth of all car and light truck sales in the United States by 2030.

The survey tells us one thing clearly: the fossil fuel industry is not prepared for this transition, which would only accelerate if Democrats in Congress are successful.

Last week, President Biden made a major environmental announcement that his administration will be largely restoring Obama-era vehicle fuel economy standards through 2025, which had been rolled back under the Trump administration. It’s a big deal because 30% of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions come from transportation.

Beyond restoring the standards, the president directed his agencies to develop more stringent standards beyond 2025 model years, for light- as well as medium- and heavy-duty vehicles. The goal should be 50% of new vehicles sales as zero emission in 2030.

To discuss the announcement, I appeared on KQED Forum on Tuesday and KTVU Channel 2 News in the San Francisco Bay Area last week. The radio audio is linked above and I’ve included the KTVU video below.

This week, Ford unveiled an electric “lightning” version of its best-selling F-150 truck. Why is this potentially a big deal? This truck is America’s most popular vehicle, and has been for 40 years. Ford sold more than 203,000 F-series trucks in the first quarter of this year, compared with a combined total of 98,000 electric vehicles in the same period.

Perhaps more significantly, electric vehicles have yet to be introduced for the truck market, although Tesla, GM, and start-up Rivian all plan to introduce one. So this vehicle finally fills an important void in the market.

There are two other significant upsides to the vehicle. First, it’s relatively low priced, at least the basic model, at about $40,000. Add in $7,500 in federal tax credits, plus possibly $2,000 in saved fueling costs each year, and the vehicle is competitive with most low-end gas-powered trucks. Of course, the high-end version is almost $90,000.

Another potential upside is the fact that Ford is partnering with solar-and-battery installer Sunrun to allow the vehicle to provide backup power to homes. That means the battery in the vehicle can also power your house during outages, a topic of greater interest after recent outages in California due to wildfires and extreme heat and in Texas due to record cold. Automakers have otherwise been reluctant to provide this customer access to the vehicle’s batteries, out of concern over impact to battery life and potentially, at least for Tesla, due to its possible negative impact on sales of their stationary batteries (the PowerWall).

This added home-backup feature could help jump start competition among EV automakers to allow vehicle batteries to power buildings, which would be a good thing. It taps into an additional benefit of EVs, so consumers can assume they’re not just buying a car but a home generator. It also can help build in society-wide resilience to extreme weather and potentially help reduce grid emissions if people power their homes off the vehicle during times of electricity supply constraints that might otherwise be met by dirty power.

But two concerns remain with the F-150. First, some customers buy trucks to haul heavy stuff. But these big loads can greatly reduce battery range. Ford is trying to be transparent in calculating how weight will impact range. But given the lack of public fast-power charging infrastructure, will this inhibit sales? Truck buyers may not want to wait around 30 minutes to repower the vehicle every 100 miles, if they can even conveniently find a charging station.

Second, while the home battery backup option is intriguing, will it become functionally impractical for most consumers, if it requires expensive upgrades to building electrical panels? The truck power will require at least 80 amps of available capacity on a home service box, but most homes have between 100 and 200 amp capacity to start. So there may be little extra capacity available for wiring in a load of that size, without a costly upgrade.

We’ll have to wait and see, but it’s encouraging that a new type of electric vehicle model is now on the market. Especially one that can appeal to a much broader range of consumer, such as those in conservative states that have historically been anti-EV and generally opposed to clean energy technology. Yet it’s just the tip of the iceberg on electric trucks, as Ford will soon find itself competing head-to-head with Tesla, Rivian and GM in this lucrative e-truck market.

But at least one consumer already seems sold on the electric F-150. Here’s President Biden taking a spin on Ford’s test track this week:

If you follow the press releases of some traditional automakers these days, you might think they are fully committed to an all-electric vehicle future. Since the election of President Biden, companies like General Motors and Ford for example have pledged billions toward electrifying their entire lineup of vehicles.

Yet sales data, company behavior, and policy advocacy reveal a different story. They show a legacy auto industry struggling to compete in a future of all-electric vehicles, with EV products that are falling behind industry-leader Tesla and a generally weak commitment to the needed policies and infrastructure investment.

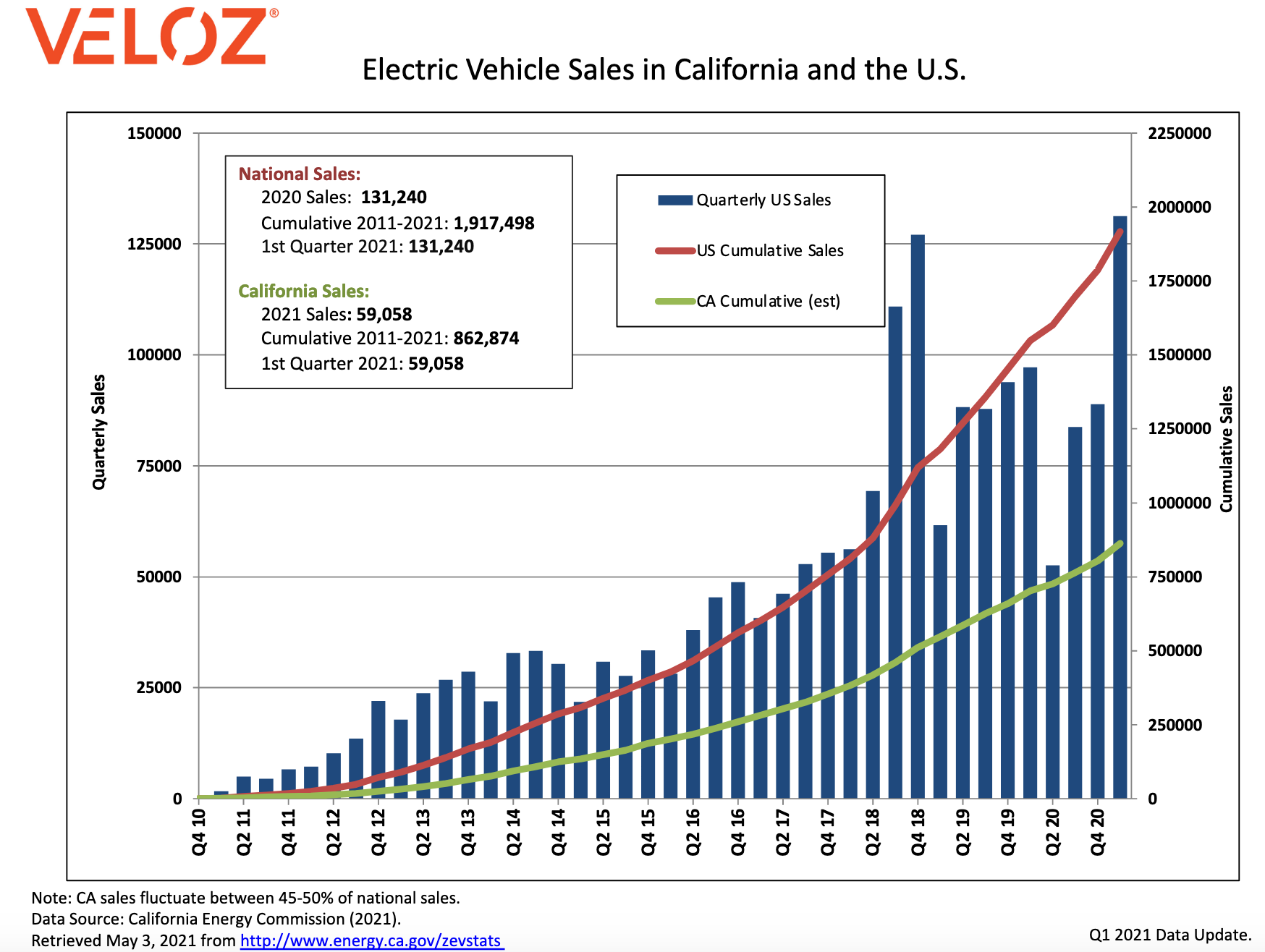

First, look at the sales data. Legacy automakers badly trail Tesla, both in California and nationwide. As a snapshot in California during the first quarter of 2021, as compiled from state agency data by the nonprofit Veloz, Tesla’s Model Y (see photo below) was the top-selling electric vehicle model in the state at 15,265 units sold, with the Model 3 second at 14,536. Next up is the Chevrolet Bolt EV, a vehicle that has remained virtually unimproved since its debut four years ago (though slated to get a minor upgrade this year), at a distant third with 5,252 units sold. The plug-in hybrid (not a true all-electric model) Toyota Prius Prime was fourth at 4,081 sales.

Nationwide, the sales gap is just as stark, according to Car and Driver. The Model Y was again the number one selling EV at 33,629 units in first quarter 2021, more than all other non-Tesla EVs combined. Next was Tesla’s Model 3 at 23,110 units. The Chevy Bolt came in a distant third again at 9,025 units, with the newcomer Ford Mustang Mach-E fourth at 6,614 units sold. Next was Tesla’s Model X at 5,106 (potentially seeing a demand pause ahead of an anticipated update), Audi e-tron and e-tron Sportback at 4,324, and then the Tesla Model S at 4,155 (also ahead of an update and range boost). Notably, the once market-leading EV Nissan Leaf, which like the Bolt has seen little improvement in the decade since it was introduced, clocked in at just 2,925 units sold.

Why are legacy automakers so far behind Tesla in this crucial new technology? Unfortunately, their products and technology are not keeping up with Tesla, though they do tend to have superior reliability and build quality. Most of the traditional automakers’ EV products have shorter range on a single charge, slower charging, and more limited access to EV charging stations. And yet some of these vehicles are actually priced higher than lower-priced Tesla’s, with the companies relying instead on continued access to federal EV tax credits, which have reached their limit for Tesla buyers.

By contrast, Tesla’s leadership had the vision and commitment early on to develop electric vehicle products that consumers want, while investing aggressively in electric vehicle infrastructure and battery and charging technology innovation. For example, Tesla paid for their high-powered Supercharger stations as loss leaders to help sell the vehicles, recognizing that concern over limited access to public charging was a major issue for potential customers. And these Supercharger stations can typically charge the vehicles at a much faster rate than what most non-Tesla EVs can handle.

Despite the press releases on EVs, legacy automakers continue to invest heavily in manufacturing and selling large gas-guzzling SUVs. As General Motors CEO Mary Barra commented recently via Reuters:

Barra added the No. 1 U.S. automaker was focused on maximizing production of high-demand vehicles like the full-sized Chevrolet Silverado pickup, and GMC Yukon, Chevy Suburban and Cadillac Escalade SUVs.

Those polluting trucks and SUVs are a far cry from the all-electric, clean future Barra promises to other audiences. And on infrastructure, these automakers have largely refused to help pay for the charging stations needed to compete in this new field to sell their vehicles, instead relying on third parties and public subsidies.

The companies’ behavior on policy similarly mirrors this weak commitment to EVs. Most if not all traditional automakers have resisted zero emission vehicles policies from the get-go, including fighting California’s landmark zero-emission vehicle mandate from its inception in the 1990s. Up until the most recent presidential election, companies like General Motors and Toyota were eager to side with Trump Administration’s attempted rollbacks of national clean vehicle policy (though notably Ford, Honda, Volkswagen and BMW sided with California). That rollback (now stopped by Biden) would have been a significant setback to the pace of vehicle electrification and climate policy in this country.

But is it all doom and gloom for these companies? Yes and no. Some may now be so far behind on electrification that they might eventually go the way of Kodak and Radio Shack, as hard as it may be to believe now. Others are rapidly trying to pivot and adapt. For example, Volkswagen, after getting caught cheating on its vehicle emissions data, has now been forced to develop new EV product lines, and its new ID 4 crossover vehicle may hold some promise. Other new models, including electric trucks, may also soon prove popular.

But it’s difficult to imagine where the U.S. and the broader electric vehicle industry would be on transportation electrification without Tesla. If not for Tesla, EV sales would be paltry. Legacy companies would likely continue to build the bare-minimum “compliance” cars needed to meet California’s zero-emission vehicle mandate. Automakers would probably still be complaining that EVs are unrealistic, infeasible and not want consumers want. As a result, it would be impossible to meet long-term climate goals, given how much the transportation sector contributes to greenhouse gas emissions.

Fortunately, we’re in a better place now with electric vehicles. Plug-in electric vehicles constituted 9 percent of new car sales in California, the largest EV market in the U.S., with approximately half of nationwide sales (see chart below). It’s decent progress toward a statewide goal of 100% zero-emission vehicles sales by 2035. By comparison, 20% of new car sales in China’s major cities are plug-in vehicles, as Bloomberg reported, with the European Union as a whole at 6.7% market share in 2020, projected to rise to 8.5% this year, per Forbes.

Thanks to this progress, EVs have now broken into the mainstream, providing the credibility to underpin Biden’s new infrastructure plan for boosting them, which includes significant new subsidies and incentives for electric vehicles and charging infrastructure.

But we’ll need many companies to get in on vehicle electrification, including the legacy automakers, both to provide sufficient products for the market and also ensure competition to keep prices low and encourage innovation. At this rate, it’s an open question whether traditional automakers can rebound for the long haul, or if the automakers of the future will instead come from new EV players that follow in Tesla’s footsteps.

Because while the electrification of vehicles is inevitable, the future of the auto industry is decidedly not.

On tonight’s State of the Bay, we’ll dive into the push to end single-family zoning restrictions in Berkeley with Vice-Mayor Lori Droste and UC Berkeley’s Stephen Menendian.

We’ll also talk with Magnus Lofstrom of the Public Policy Institute of California about rising crime rates in the Bay Area. And then Grace Won chats with local author Vendela Vida about her new novel, We Run the Tides, which explores the rocky terrain of teenage friendships, particularly among girls.

And as a bonus, I’ll be on Your Call on KALW 91.7 FM at 10am PT discussing electric vehicles and the Biden infrastructure package!

Tune in today at 10am PT for Your Call and at 6pm PT for State of the Bay or stream live, both on KALW 91.7 FM in the San Francisco Bay Area. Call 866-798-TALK with questions during the show!