The big fossil fuel companies wanted to avoid paying for the carbon pollution from their products via California’s cap-and-trade program. They tried to scare California residents about the looming gas price increases. They found an ally in Assemblyman Henry Perea (D-Fresno), who introduced AB 69 to delay including fuels under the cap. As I blogged about a few weeks ago, the money for the fuel pollution allowances would fund transit and electric vehicle programs, among other pollution-reducing technologies.

Now good news: State Senate President Darrell Steinberg prevented Perea’s bill from even coming up for a vote. That avoids the messy political problem of forcing legislators to weigh in on this issue during an election year. As I wrote about, the gas price increase is likely to be negligible, and there’s no reason oil companies can’t simply absorb the cost from their $200 billion annual profits, rather than passing it along to consumers.

Steinberg wrote a forceful letter to Perea explaining his logic, worth reading in full. So now fuels will come under the cap on January 1st, and California will use the revenue from the pollution allowances to fund the ongoing transition to a cleaner, cheaper and more sustainable form of transportation. And once under the cap, it will be difficult for the oil and gas interests to remove it later. Overall, this is excellent news for California’s fight to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and bolster our clean tech sector.

Steve LeVine over at Quartz has an excellent write-up of the Tesla versus General Motors showdown to build the first mass market, long-range EV:

The stakes are enormous. Most electrics have less than 100 miles of range. Experts regard 200 miles as a tipping point, enough to cure many potential electric-car buyers of “range anxiety,” the fear of being stranded when their battery expires. If GM and Tesla crack this, sales of individual electrics could jump from 2,000 or 3,000 vehicles a month to 15 to 20 times that rate, shaking up industries from cars to oil, which were until now certain that large-scale acceptance of electrics was perhaps decades away.

LeVine traces the economic and engineering challenges to bring battery costs down so dramatically. Musk is betting on economies of scale through mass production. But the scientific consensus is dubious. Experts point to the difficulty of building a better anode (the negative electrode):

All current lithium-ion batteries use graphite anodes. But scientists say a big jump in performance would be possible if they could perfect a silicon anode, which would absorb far more lithium than graphite, increasing how much energy could be stored. The problem is that in tests thus far, silicon expands, cracks and kills the battery. The US government is funding six efforts to create a working silicon anode that can go commercial, but even if one or more are successful, they would not deliver a 200-mile car by 2017 or 2018.

Meanwhile, Nissan is quietly improving the LEAF’s battery range. By 2020, given the current decreases in battery costs, Nissan may be able to offer a 170-mile model for the current price (approximately $29,000).

It’s very encouraging to see so much capital and ingenuity devoted to cracking this battery code. Let’s hope for success and that it happens quickly.

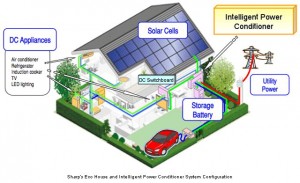

The best hope we have on Earth for averting the worst impacts of climate change is a pretty simple formula: a huge amount of renewable energy, with surpluses stored in technologies like cheap batteries, and all our transportation running on electricity.

Well, actually there’s another solution: we could de-industrialize and return to the Stone Age. Or humans could die off suddenly from disease or war. But I prefer the first approach.

The critical piece to this energy and transportation transition is bringing the cost of these technologies down, and two articles this week indicate that we’re making progress. First, solar prices have come down dramatically, leading to huge new demand which is now causing a shortage of panels. Analysts don’t expect solar panel prices to rise in response, but it is prompting companies like SolarCity to invest heavily in new solar PV production facilities. Underlying this dynamic is the fact that panels now sell for 76 cents a watt, compared with $2.01 at the end of 2010 (including a 12 percent price drop just this year).

The critical piece to this energy and transportation transition is bringing the cost of these technologies down, and two articles this week indicate that we’re making progress. First, solar prices have come down dramatically, leading to huge new demand which is now causing a shortage of panels. Analysts don’t expect solar panel prices to rise in response, but it is prompting companies like SolarCity to invest heavily in new solar PV production facilities. Underlying this dynamic is the fact that panels now sell for 76 cents a watt, compared with $2.01 at the end of 2010 (including a 12 percent price drop just this year).

Second, wind prices are falling, making wind energy competitive with natural gas in some parts of the country:

After topping out at nearly $70 per megawatt hour in 2009, the national average levelized price of wind purchase agreements fell to around $25 last year, the [U.S. Department of Energy] report sad. That means wind electricity costs about 2.5 cents per kilowatt hour, a highly competitive price in some parts of the country.

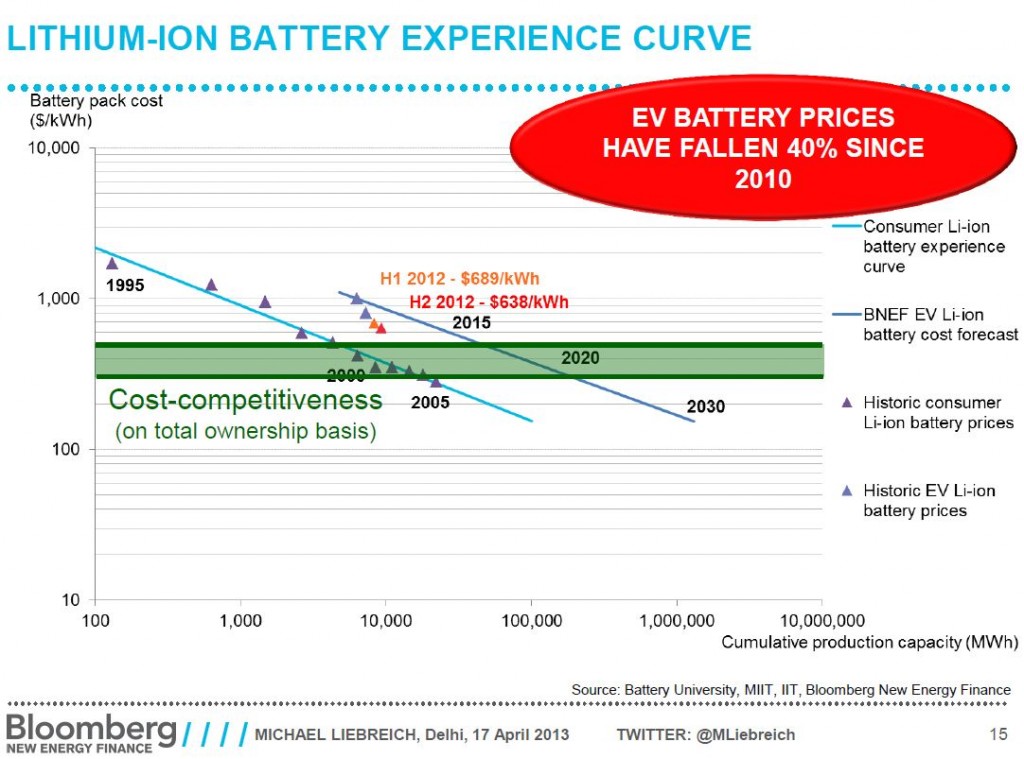

Finally, as I blogged about earlier this week, electric vehicle battery prices have dropped 40% since 2010.

This is all great news for the possibility of an economically painless transition to a sustainable economy. Credit so far is due to the private sector for the innovation and investment. But this is also a clear sign that government policies around the world to boost these markets are having success. On the solar and wind side, the federal government offers tax credits for investors, while many states have renewable energy mandates, financial incentives, and utility programs that reward customers for installing renewables. The federal government also provides a tax credit for electric vehicle purchases and loans and grants for clean technology startups (in some ways, the 2009 economic stimulus was Obama’s true climate change bill, given the support that legislation gave to game-changing companies like Tesla). And states like California offer cash rebates and other incentives for EV purchases, as well as a mandate for utilities to buy more energy storage.

Obviously we still have a long way to go, but the cost trends are very encouraging. And they should reinforce the political will to keep the incentives going while the private sector continues to do its part to bring down costs.

A new report (subscription required) in Transportation Sciences suggests that EV buyers would be better off purchasing cars with battery ranges of less than 100 miles. Why? That range covers the vast majority of their trips for the cheapest vehicle price, particularly as battery prices decline. And an expanded public charging infrastructure with cheap electricity would cover longer trips less expensively than buying a higher-priced, big battery EV. To gauge consumer demand, the study relied on a 2009 survey of more than 36,500 drivers and their driving patterns. Notably, it did not rely on any new data from consumers in response to specific questions about EV preferences related to range.

Perhaps as a result of this lack of consumer preference data on EVs and battery range specifically, the study is already getting some raised eyebrows at Green Car Reports:

Sometimes mathematical logic is simply swept aside by the more primal emotions: fear, anxiety, and insecurity. Which is why so many car buyers make choices that cost them money in the long run. Some of those choices may be luxury items they want but don’t need; others may be capabilities they’ll rarely, if ever, use but want to have in case of unusual circumstances. The choice of vehicle range for a battery-electric car turns out to be one of those decisions where fear of what could happen decisively trumps what probably will be.

I think most consumers would pay more for EVs with bigger batteries to maintain the convenience they have with gas cars of not having to worry about recharging on long trips. They want a car that meets all their driving needs, and if they just wanted cheap, they could buy an inexpensive fuel-efficient economy car (or used car) and save a lot on gas that way. Eventually, automakers will produce a range of battery sizes in the vehicles, so we’ll see how the market shakes out. And certainly we need a better public charging infrastructure anyway. But charging takes time, and most people don’t want to have to even think about it. So my guess is that cars like the LEAF will become a lot more popular once they improve the range while keeping the price steady.

I posted a few weeks ago about the hydrogen fuel cell versus battery electric vehicle debate, citing alternative fuel expert Joe Romm’s evidence. Romm is back at it, highlighting the high costs and lack of environment benefits of hydrogen fuel cells:

The biggest problem hydrogen fuel cell vehicles face is that they deliver no obvious major consumer (or societal/environmental) benefit compared to the competition, but have a bunch of obvious consumer defects. These defects include high first cost, high fueling cost (compared to both gasoline and electricity), lack of fueling stations and lack of a nationwide fuel-delivery infrastructure — especially for renewable hydrogen.

Romm also describes the significant price decreases seen over the past few years in lithium ion batteries:

[M]assive amounts of money were poured into improving batteries and related components, not just by governments, car makers and clean energy venture capitalists, but also by portable device and phone manufacturers who wanted to improve performance while cutting costs. The results in the case of batteries have been impressive:

Between these highly encouraging battery cost reductions and the corresponding steep mountain to climb on hydrogen fuel cells, I continue to wonder why California just invested $50 million in this dubious technology.

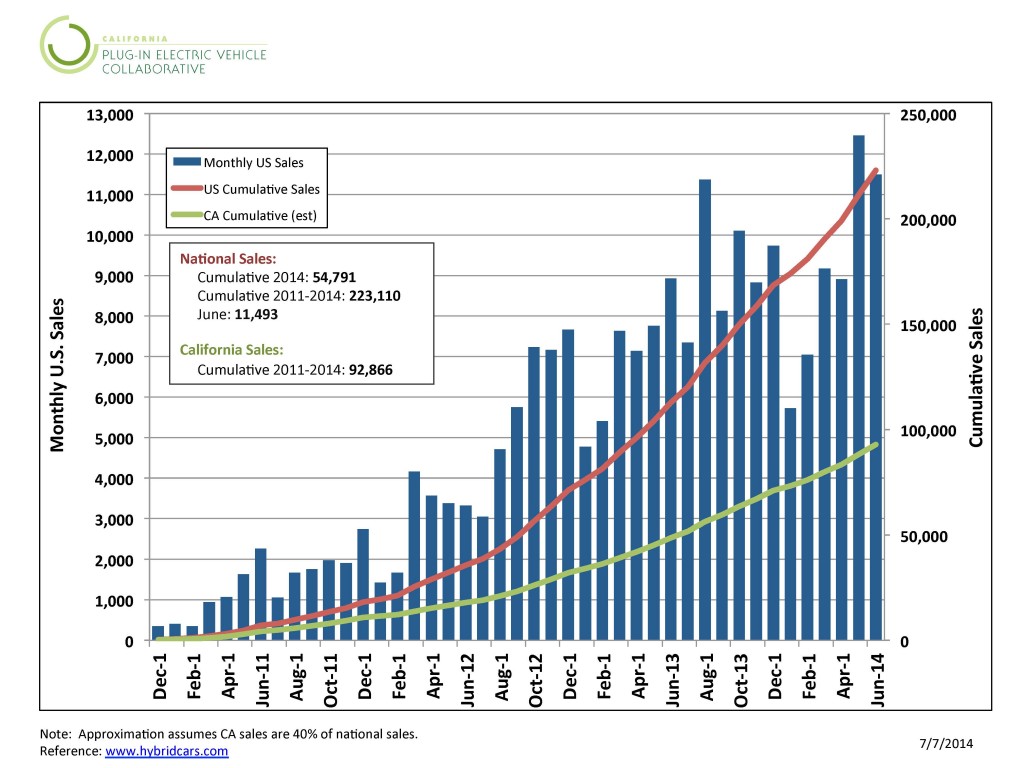

The website Clean Technica presents interesting information on electric vehicles sales compared to top car sales in the US generally. The news is mixed but to my mind ultimately positive. The bad: EV sales are pretty tiny compared to ICE (internal combustion engine) vehicles, with no true EV cracking the top 20. The Toyota Prius Plug-In (with the first few miles all-battery electric but then traditional hybrid miles from thereon) hit #15. But:

13.5 times more units of the Toyota Camry were sold than the top-selling electric car, the Nissan Leaf.

However, the overall trajectory of the EV sales is outpacing hybrids at a similar stage of introduction, and this disruptive technology is showing a hockey stick-like sales trajectory. Here’s the most recent EV sales chart from the PEV Collaborative:

And as the Clean Technica post notes:

If the Nissan Leaf quadrupled its sales (or if the Tesla Model III came along and sold 4 times as many cars per month as the Leaf), it would make it into the top 20 best-selling cars in the US.

Quadrupling sales doesn’t seem like that big of a feat giving how fast sales have been increasing, the fact that most Americans still aren’t aware of the Nissan Leaf, and the fact that disruptive technologies see exponential growth, not linear growth.

EV companies and advocates still have a ways to go with the technology: we need cheaper vehicles with a longer range. Tesla’s gigafactory is the big hope in this respect, but even without a game-changer factory, the technology is steadily improving and becoming cheaper. The sales data we see here, to my mind, offers cause for cautious optimism.

I joined Larry Mantle on his KPCC radio talk show in Southern California this morning for a discussion of State Senator Kevin De Leon’s bill to limit California’s electric vehicle rebate program (up to $2500 off purchases) to low and moderate income customers. The LA Times covers some of the debate here. SB 1275 would direct the California Air Resources Board to figure out the best way to spend limited rebate funds by limiting access to high-income earners.

I joined Larry Mantle on his KPCC radio talk show in Southern California this morning for a discussion of State Senator Kevin De Leon’s bill to limit California’s electric vehicle rebate program (up to $2500 off purchases) to low and moderate income customers. The LA Times covers some of the debate here. SB 1275 would direct the California Air Resources Board to figure out the best way to spend limited rebate funds by limiting access to high-income earners.

My take? California’s overriding goal should be to maximize electric vehicle adoption rates, and if targeting limited public funds on low-income communities is the way to do it, then please proceed. It makes sense in some ways: over half of Tesla owners did not cite the rebates as a motivating factor in their purchases. So why not redirect some of that rebate money to lower-income people where it would make a difference?

A number of listeners on the show today disagreed, and some even took offense that “successful” people were being “punished” by this bill. Personally, I think the state has a strong interest in maximizing the value of limited public funds, and if that means supporting low-income people and helping to expand the market in those communities, let the state go with it. I’m sure many of those listeners would also be upset about their tax dollars not being spent in the most efficient manner, either.

The link to the interview is here.

California recently committed to spending $50 million on 28 public hydrogen fuel cell charging stations, throwing gasoline (bad pun) on the fire of a growing debate: electric vehicles vs, hydrogen fuel cells as the carbon-free vehicle technology of the future. California policy makers seem to think it may be both, based on their spending to support the two technologies.

But the evidence to date suggests that hydrogen fuel cells, which automakers like Toyota are committed to, may actually be “fool cells,” as Tesla CEO Elon Musk calls them derisively. Joe Romm, expert on alternative fuels from the US Department of Energy and author of a 2004 book on the debate, takes a strong position against hyrdogen fuel cells. His point? The fuel (hydrogen) will come from dirty sources for the foreseeable future, compared to clean, electric-powered battery vehicles:

Converting cheap fracked gas into hydrogen is very likely going to be substantially cheaper than practical, mass-produced carbon-free hydrogen for decades, certainly well past the point we need to start dramatically reducing transportation emissions (which is ASAP).

For EVs, on the other hand, unsubsidized renewable electricity is already directly competitive with grid electricity in many parts of the country — and poised to continue dropping in price. In places where carbon-free power is on the rise, such as California, the electricity is already far less carbon intense than the nation as a whole. That’s why EVs in a state like California is already super-green.

In terms of climate change impacts, Romm is clear:

So from a greenhouse gas perspective, there is no competition between pure electrics and hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles. EVs win hands down and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future.

I’m all in favor of fostering competition among promising clean vehicle technologies, but Romm’s critique points to the significant environmental disparity between these technologies, at least in the short term. In addition, there is a huge expense associated with developing an entirely new fuel infrastructure for hydrogen. EVs, by contrast, can access ubiquitous electricity throughout our developed areas. It’s also disappointing to see California commit to spending so much public money on a technology that consumers are not demanding, particularly given the ongoing need for investment in new EV charging stations in the state.

EVs certainly have a ways to go in terms of decreasing costs and increasing battery range. But automakers are making progress and consumers are responding. If companies like Toyota think hydrogen fuel cells are a better deal for California drivers and the environment, then let them spend their own money to prove it.

Western states like California are falling all over themselves to secure Tesla’s proposed “gigafactory” to mass-produce lithium ion batteries. This cheap energy storage will be a game changer for making electric vehicles affordable and decarbonizing our electricity supply by balancing intermittent renewables from the sun and wind. But for state leaders, the factory means great middle class jobs in an expanding clean-tech industry.

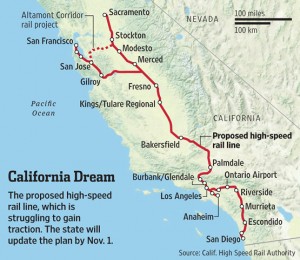

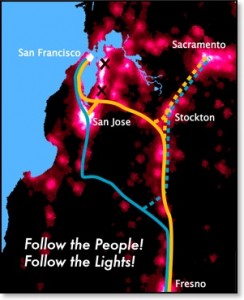

Texas seemed to have the lead, but California is pulling out all the stops, including waiving key environmental laws like the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). Now it appears that if the factory happens in California, it may be in Stockton, according to the Los Angeles Times. Stockton is just an hour outside of the Bay Area in the Central Valley, with many people commuting into the Bay Area there from cheaper middle-class sprawl developments. Plus it has access to waterways, freeways, and the Tesla vehicle factory.

But if the factory does happen in Stockton, it should also have access to high speed rail. A decision to locate the gigafactory there should prompt the California High Speed Rail Authority to reconsider its proposed route to the Bay Area from the south via Pacheco Pass and pristine, rural San Benito County. That route is not my favorite — it cuts off major population centers, including Stockton and Modesto, and puts a beautiful, undeveloped part of the state at risk of rail-induced sprawl. It does serve San Jose more directly, but the city could still be served by a spur from an Altamont route. Here’s the current proposed route:

And here’s the alternative Altamont Pass route that would provide access to Stockton and the possible factory (source is the advocacy group Transdef):

And here’s the alternative Altamont Pass route that would provide access to Stockton and the possible factory (source is the advocacy group Transdef):

The Authority just won a CEQA case on appeal upholding environmental review on the Pacheco alignment. But maybe the prospect of the gigafactory, combined with the other benefits of routing the system along Altamont, will prompt long-overdue reconsideration.

The Authority just won a CEQA case on appeal upholding environmental review on the Pacheco alignment. But maybe the prospect of the gigafactory, combined with the other benefits of routing the system along Altamont, will prompt long-overdue reconsideration.

I just returned from a road trip through the Pacific Northwest, including Oregon (Cascades, Willamette Valley and Portland) and Washington (Seattle and the San Juan Islands). So of course I’m now an expert on the environmental trends there, as seen from the window of my car and my conversations with friends and strangers there. Based on this purely anecdotal evidence, I’ve compiled my list of top five environmental trends in the Pacific Northwest.

5) Farm-to-Fork: Lots of great agriculture in the Northwest, and they take advantage of it. Much of the food we ate on our trip, whether purchased at farmers markets, restaurants, or eaten at friends’ houses, came from hyper-local sources. At one cafe in the San Juan islands, all food was either grown at the farm on-site or traded/purchased from other local farms, including a nearby brewery.

4) Rail Transit: Portland and Seattle are undergoing a light rail construction boom. Seattle just recently began theirs, and we saw new tracks going in near the downtown, while Portland’s MAX system is extending south of the city. Plus Portland has a cool-looking (although I gather cost-ineffective) gondola tram linking two parts of their hospital complex that are separated by a hill.

3) Renewable Energy: Particularly in Oregon, we saw some innovative renewable energy arrays. Portland State University features the first solar “arch” that I’ve seen (photo right),

while another building in downtown had cool-looking wind turbines up top (photo left).

Bonus points for its energy efficient ventilation system through windows that can open to the street (remarkably unusual in most skyscrapers).

2) Infill Development: Portland and Seattle featured cranes galore on multistory apartment buildings near their downtowns. Seattle’s trendy Eastlake neighborhood and Portland’s Pearl District stood out to me for construction in these transit-friendly neighborhoods. One negative: Seattle’s Safeco Field baseball park has failed to stimulate much development in the otherwise industrial area south of downtown. I can only assume it’s a failure of planning and financing, but maybe it’s just not a great area for homes and businesses given the industrial activities going on.

1) Electric Vehicles: while California is still the leader here, Oregon features great signage for EV charging stations along the highway (see photo on the right).

Washington State also seemed to have a good presence of EVs on the road. We even saw a Tesla Model S on Orcas Island in the San Juans (an hour ferry ride from the mainland) with California plates! If that car wasn’t shipped there, then that’s a real coup for Tesla’s supercharger network along I-5.

Overall, it’s great to see other West Coast states making such progress on environmental and energy needs. One area of improvement: Washington State should definitely improve its tailpipe regulations — cars and trucks there are quite smelly and polluting. And of course we need both states to join California’s cap-and-trade market. But I’m confident that in the long run, the West Coast will help lead the country in smart policies to clean the environment and build a sustainable economy.