Some good laws are now in effect on both rooftop solar and electric vehicles in California. I blogged about AB 2188 once it passed the California Legislature, which will require local governments to adopt streamlined ordinances for permitting rooftop solar. The governor signed it, which will be helpful for reducing the cost of installing solar, possibly up to 20 cents per watt.

In addition, as I discussed on KCRW radio on Monday, the governor signed AB 2013 (Murastsuchi) to increase the number of “green stickers” available for partial electric/hybrid vehicles to access carpool lanes, as well as SB 1275 (De Leon) to limit cash rebates for electric vehicles based on income. The latter bill directs the California Air Resources Board to come up with an overall, long-term financial plan for supporting electric vehicles, taking into account anticipated price declines on the vehicles. That plan will likely include a phase-out for the rebates and may explore other options, such as point-of-sale cash rather than having to apply for the rebate after purchase.

In addition, as I discussed on KCRW radio on Monday, the governor signed AB 2013 (Murastsuchi) to increase the number of “green stickers” available for partial electric/hybrid vehicles to access carpool lanes, as well as SB 1275 (De Leon) to limit cash rebates for electric vehicles based on income. The latter bill directs the California Air Resources Board to come up with an overall, long-term financial plan for supporting electric vehicles, taking into account anticipated price declines on the vehicles. That plan will likely include a phase-out for the rebates and may explore other options, such as point-of-sale cash rather than having to apply for the rebate after purchase.

With these bills, California is continuing its leadership on renewables and electric vehicles, and hopefully making our public sector incentives more efficient and streamlined in the process. I’m glad the governor signed them, showing that we’re making incremental progress on these vital technologies.

For anyone in Los Angeles or who has an internet connection with audio, I’ll be on KCRW radio today at noon talking about the new electric vehicle bills that Governor Brown signed into law this weekend. It’s the Madeleine Brand “Press Play” show, link here.

UPDATE: The broadcast is now archived here. I go on about 8 minutes in, for the second story of the day. You can also access it directly if you scroll down the page to the “Brown Signs Electric Vehicle Bills” link.

UC Berkeley Law will be hosting a webinar this morning from 10 to 11am Pacific Time on repurposing used electric vehicle batteries. It will feature:

- Adam Langton, Senior Energy Analyst, California Public Utilities Commission

- Randall Winston, Special Assistant to the Executive Secretary, Office of Governor Edmund G Brown, Jr.

The webinar will discuss the challenges and solutions to boosting a secondary market for the batteries. The market is still new and uncertain, and used EV batteries are only just now being deployed in various grid scenarios. The webinar comes on the heels of a new UCLA and UC Berkeley Schools of Law report, entitled Reuse and Repower: How to Save Money and Clean the Grid With Second-Life Electric Vehicle Batteries. I will be speaking on the key findings.

More information on the event can be found here, including the registration page. We will include time for questions from the audience.

Over the past two days, I attended the Battery Show conference outside of Detroit, Michigan, to hear what the leading entrepreneurs, researchers and automakers have to say about the state of electric vehicle batteries. While I was there to speak on a panel about a new report on repurposing electric vehicle batteries, I picked up some interesting themes about the most important clean technology out there, the battery. Here they are:

Carbon regulations & clean energy policies have been critical for pushing the battery market. Speaker after speaker spoke about the growing global policies on carbon, from California to the US EPA rule on power plants to Japan and China’s new emphasis on reducing pollution. Industry leaders estimate that the carbon regulations will result in a 4% per year rate of change in carbon emissions going forward. But the policies also include non-climate focused efforts, such as the new U.S. fuel economy standards. From 1975 to 2011, CAFE standards required only a 1.3% improvement per year on average, but from 2012 to 2025 they will require a 4.5% per year improvement, greatly benefiting clean vehicle technologies like EVs. And of course California’s leading policies on zero-emission vehicles and energy storage in general is providing a critical market foundation. One speaker said “we wouldn’t be here today talking about these issues without California’s leadership.”

Lithium ion is still the most promising battery technology, with continued price reductions but no overnight breakthroughs. Speaker after speaker praised lithium ion as still the best battery technology out there, given its high energy density and low weight. Nobody foresees any other technology out there to rival it. In terms of cost and advances, it’s clear that costs will continue to decline, although not precipitously. By the end of this decade, most speakers believed Tesla will either achieve or come close to achieving the magic price/range of 200 miles per charge in a $35,000 EV. Improving manufacturing supply chains and automation will help tremendously, as the Tesla Gigafactory will be able to do.

Lithium ion is still the most promising battery technology, with continued price reductions but no overnight breakthroughs. Speaker after speaker praised lithium ion as still the best battery technology out there, given its high energy density and low weight. Nobody foresees any other technology out there to rival it. In terms of cost and advances, it’s clear that costs will continue to decline, although not precipitously. By the end of this decade, most speakers believed Tesla will either achieve or come close to achieving the magic price/range of 200 miles per charge in a $35,000 EV. Improving manufacturing supply chains and automation will help tremendously, as the Tesla Gigafactory will be able to do.

EV drivers want performance, not necessarily environmental benefits. Marketing and survey data clearly show that buyers concerned about fuel economy and environmental performance do not make up a huge percentage of the market. Instead, they want performance, style, and access to technology. Tesla has hit this magic formula well, as they downplay the environmental benefits of going electric. Perhaps Nissan should follow suit and rename the LEAF something less “green” sounding. After all, when I tell people what I like about my electric car, I always start with the superior performance of the electric drive, and then I finish by touting the fuel savings (which are huge) and the environmental benefits. I don’t do this strategically: it’s just the truth about what I’m most excited about with the car.

Repurposing batteries is a big open question, with lots of opportunities but lots of unknowns. Since it was the subject of my report, I was keen to hear people’s take on this topic. Many speakers who addressed the issue felt the potential is huge, noting the amount of energy storage available in electric vehicle batteries on the road today and in the near future. But many felt that these batteries would have to compete with the cost of recycling the batteries, which could become much cheaper through automation. And there are unknowns about how easy and cheap it will be to collect, verify, and stack the batteries for high-performance energy storage. But given the size of the opportunity and the environmental need, I encourage policy makers and industry to start analyzing the opportunities as thoroughly as possible, as outlined in the report.

Overall, it was a well-run conference that attracted an impressive group of speakers and leaders in the field. Cheap batteries will not only revolutionize transportation through electric vehicles, they will clean our grid when coupled with renewable resources. The solar+storage combo may also change the utility world forever: after all, who needs a utility if you and your neighbors can generate and store your own clean power? The disruption continues, while Michigan feels like a dream to me now.

On the heels of the new UC Berkeley/UCLA Law report on harvesting “second life” electric vehicle batteries, the Sacramento Bee is running an op-ed from me today on the topic. You can read it here. As I write in the piece, even with the Tesla Gigafactory going to Nevada,

California still has an opportunity to boost an entirely different battery supply market, one that will also help the state clean our energy supply and reduce the cost of electric vehicles in the process. The answer lies not in manufacturing new batteries, but repurposing used ones.

Let’s hope policy makers take note and take the steps necessary to boosting this new market.

As I blogged about last week, California and the nation may have a golden opportunity to harvest used electric vehicle batteries for inexpensive energy storage. These repurposed batteries can be stacked for bulk storage to absorb surplus renewable energy for cloudy and dark windless times. They can save ratepayers money, clean the grid, and potentially help bring down the cost of electric vehicles, encouraging more people to switch from gas engines to cleaner electrics.

As I blogged about last week, California and the nation may have a golden opportunity to harvest used electric vehicle batteries for inexpensive energy storage. These repurposed batteries can be stacked for bulk storage to absorb surplus renewable energy for cloudy and dark windless times. They can save ratepayers money, clean the grid, and potentially help bring down the cost of electric vehicles, encouraging more people to switch from gas engines to cleaner electrics.

The numbers are compelling: California now has over 100,000 electric vehicles on the road today, with a goal of 1.5 million by 2025. Assuming 50 percent of the battery packs can be repurposed, with 75 percent of their original capacity, the “second-life” batteries on the road in just ten years could store and dispatch enough electricity to power 4.5 million households in any given moment, equivalent to almost 10 percent of the state’s installed power capacity.

But the market for these batteries is still new and uncertain. Used electric vehicle batteries are only just now being deployed in various grid scenarios, and automakers are concerned about uncertain liability in the event of damages, as well as the complex regulatory environment facing energy storage technologies in general.

To address the challenges and offer solutions, UCLA and UC Berkeley Schools of Law are today releasing the report Reuse and Repower: How to Save Money and Clean the Grid With Second-Life Electric Vehicle Batteries. I served as the lead author, and the report resulted from a one-day gathering of industry experts, including automakers, renewable energy developers, battery leaders, and utilities. It is the thirteenth in the law schools’ Climate Change and Business Research Initiative, sponsored by Bank of America, which develops policies that help businesses prosper in an era of climate change.

The report recommends that policy makers:

- support and partner with automakers, utilities, and other private sector entities to develop more second-life battery demonstration projects to document the market potential;

- Partner with industry leaders to identify and address the regulatory conflicts that limit the second-life battery market (often unintentionally); and

- Work with stakeholders to clarify product liability rules based on second-life battery performance standards.

To hear more about the report and the topic, UC Berkeley Law will be hosting a webinar this Friday from 10 to 11am with:

- Adam Langton, Senior Energy Analyst, California Public Utilities Commission

- Randall Winston, Special Assistant to the Executive Secretary, Office of Governor Edmund G Brown, Jr.

I will also be speaking on the report’s key findings. More information on the event can be found here, including the registration page. The webinar will include time for questions from the audience.

Federal and state gas tax revenue funds our highways, but the amount of money coming in has been shrinking dramatically. Cars have become more fuel efficient and the tax isn’t linked to inflation. States like Oregon have pioneered a mileage-based tax, and California may finally be joining. A new bill to launch a pilot project is on the governor’s desk. SB 1077 (DeSaulnier) would sign up volunteers to test out how the tax might work in practice:

Federal and state gas tax revenue funds our highways, but the amount of money coming in has been shrinking dramatically. Cars have become more fuel efficient and the tax isn’t linked to inflation. States like Oregon have pioneered a mileage-based tax, and California may finally be joining. A new bill to launch a pilot project is on the governor’s desk. SB 1077 (DeSaulnier) would sign up volunteers to test out how the tax might work in practice:

DeSaulnier emphasized that his legislation does not seek to add a new layer of taxation. Instead, it aims find an alternative to what could become an obsolete gas tax so the state can avoid what’s been called a “fiscal cliff” for highway funds.

“I don’t think people understand what dire shape our transportation funding is in,” the senator said. “We need to find a different funding source.”

Privacy advocates are concerned about the government tracking our whereabouts, but the key here is to offer options, such as having tax officials check your odometer each year rather than track your actual driving in real time. Of more concern to me is the potential disincentive to buy a fuel-efficient car, since all cars might be taxed the same. I would hope that any mileage-based tax provides discounts for electric vehicles, for example, until those technologies become widespread.

As California faces an increasing need for more energy storage to integrate variable renewables and provide other grid services, used electric vehicle batteries could be a critical – and inexpensive – part of the solution. Sales of electric vehicles in the United States are heading toward a quarter million, with 100,000 of those purchases in California. The thousands of batteries that will be coming out of the vehicles in the coming years will still retain significant capacity, although not enough to provide a sufficient electric driving range. These used, less expensive batteries can be stacked and repurposed by utilities and building owners to clean the grid and reduce costs. Plus, electric vehicle customers could see lower upfront prices if automakers factor in the long-term resale value of the batteries in the sale price.

UCSD “second life” EV battery demonstration project. Courtesy of UC Regents/Rhett S. Miller.

UCLA and UC Berkeley Schools of Law, with the support of Bank of America, will be releasing a new report next Wednesday on policies needed to help boost this market. The report resulted from a one-day convening at UCLA Law that included major automakers, renewable companies, battery experts, and public officials.

On Friday, September 19th, from 10 to 11am, UC Berkeley Law will host a live webinar, featuring representatives of the Governor’s Office and the California Public Utilities Commission to discuss the report findings. You can register here (space is limited). I hope you can join.

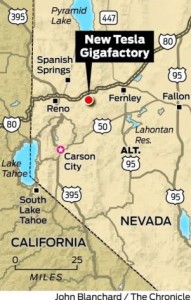

Some California environmentalists may be celebrating now that Tesla has apparently decided to build its $5 billion “gigafactory” in Nevada instead of California. Lawmakers here had toyed with the idea of weakening the state’s signature environmental law, the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), to help expedite review on the factory and therefore encourage Tesla to locate in-state, possibly in Stockton. But those plans fell through last week.

But Tesla’s decision could be an overall setback for the environment, compared to building a factory in California. To be sure, the idea of a gigafactory is a huge win for the environment overall. The cheaper batteries will encourage more adoption of electric vehicles and also help clean our grid by enabling inexpensive storage of surplus wind and solar energy.

So why is Nevada so bad, compared to California? First, the siting of the gigafactory will likely launch a major manufacturing program, with an attendant industry likely to spring up around it, in a state with much weaker regulation than California. Nevada ranked 20th among US states in a George Mason University survey of the most lax regulatory states when it comes to land use decision-making, with California ranked 49th. And a recent comprehensive survey of business owners gave Nevada an “A” on the impact of environmental regulations on business, which is not a good sign for environmental protection. California of course received an “F.” So the factory itself, as well as any future co-located suppliers, will operate with less future oversight for environmental health and safety protection.

In addition, the thousands of workers who will be employed there will likely end up in new subdivisions that sprawl over the high desert countryside, if Reno’s past growth is any indication. And they will likely commute to work by car, a lifestyle that Californians are rapidly abandoning. California meanwhile is engaging in regional transportation plans that will offer alternative, more environmentally friendly housing and transportation for workers, and its environmental laws are now encouraging growth closer to jobs and services.

Finally, from a shipping perspective, the factory in Nevada will have to transport the batteries by train to the major population centers in San Francisco and Los Angeles, which are the leading markets to buy electric vehicles. Locating the factory in Stockton would have reduced this shipping distance significantly, along with its associated environmental impacts, while placing the factory only a negligibly farther distance from the East Coast markets.

Tesla CEO Elon Musk has said that he plans to build more such factories. And as I say, the gigafactory is an overall environmental win. Yet while California’s economy would certainly benefit from locating it in-state, the environment would as well, compared to the site announced today.

The California Legislature passed SB 1275 (De Leon) last week, which would give the California Air Resources Board authority to eliminate the cash rebate incentive for wealthy people who buy electric vehicles. It would then use that revenue to increases the cash incentives for lower-income Californians.

I debated the merits of this approach on KPCC radio last month on the Airtalk program. My write-up of the debate is here. Meanwhile, Grist celebrates that electric vehicles won’t be “pretentious” anymore, as if the Nissan LEAF and Chevy Volt were glamor cars.

As I noted in my write-up, half of all Tesla Model S purchasers reported that the rebate made no difference in their decision. So why not use those funds for people who are truly on the fence without additional rebate money? The goal here for everyone should be to maximize the effectiveness of these limited rebate dollars and spur the greatest adoption possible of electric vehicles. The details will be figured out by agency experts, and that sounds fine to me. The governor has until the end of the month to sign.