Okay, this is a subjective rant. But it points to a larger failing in California’s electric vehicle infrastructure. This past Memorial Day weekend, I was set for a short vacation in Monterey, a significant regional destination about 70 miles from San Jose, south of the Bay Area.

I wanted to drive my Nissan LEAF, which gets about 80 miles range on flat elevation. From the East Bay where I live, it would require one fast-charge (80% battery recharge in about 20 minutes) just south of San Jose, which is about 60 miles from my home.

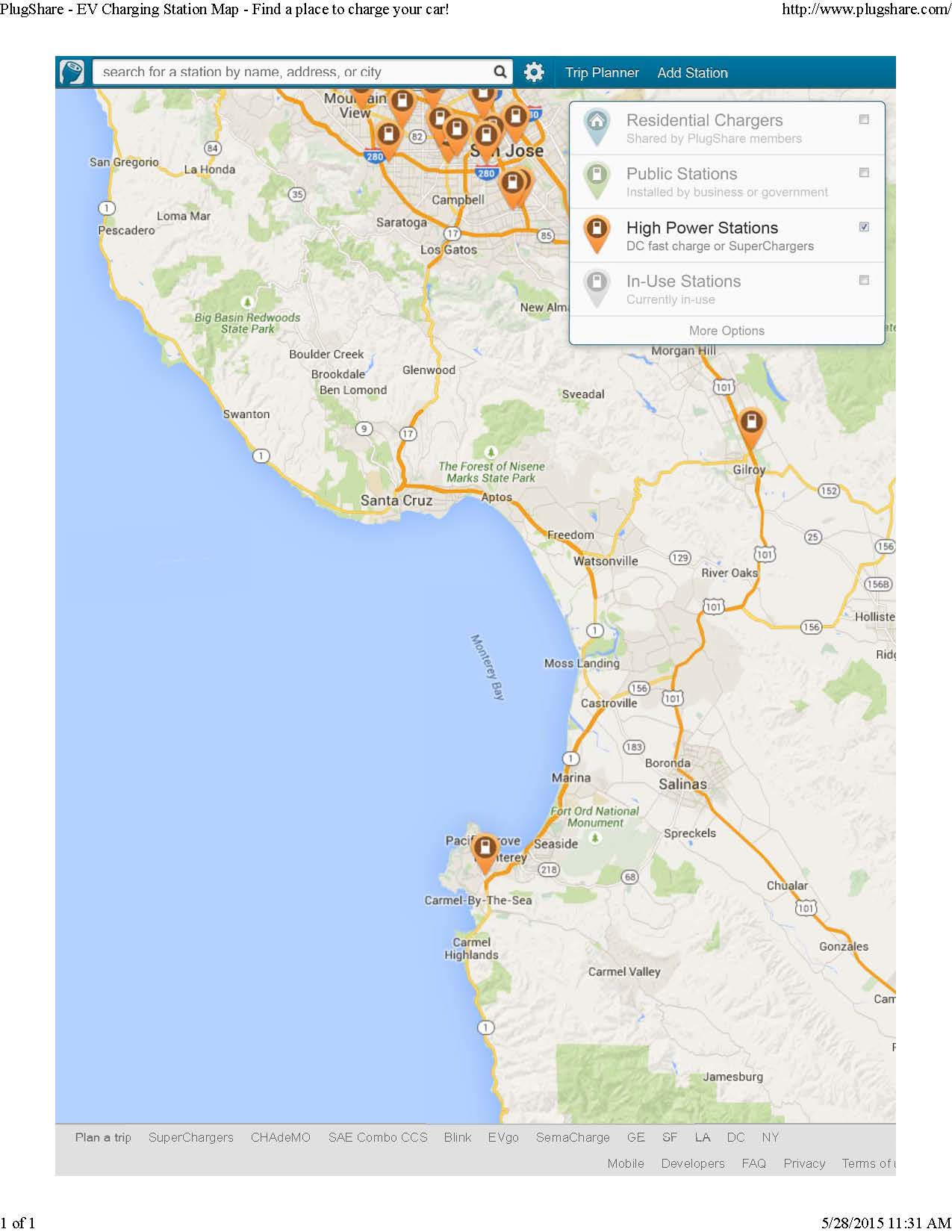

But in looking at the charging map, there are no fast chargers south of San Jose — unless you’re lucky enough to drive a Tesla of course, then you can charge in Gilroy. The fast chargers in San Jose would leave me with a white-knuckle drive to Monterey, given the elevation and distance.

Here’s a screenshot of the Plugshare.com map, with a Tesla fast charger in Gilroy but otherwise a no-man’s land of fast-chargers until you get to Carmel (about 10 miles further south of Monterey):

Why haven’t EV charging companies fixed this missing link? This route is exactly the situation for a series of fast-chargers, given that you have a major regional destination about 70 miles from a densely populated urban area.

This is why California policy makers are now auditing eVgo, the company that benefited from a $100 million settlement back in 2012 to deploy a network of chargers around the state. I wrote about it recently, but the company’s progress has been dismal. EVgo has been focusing on money-making fast-charging sites in urban areas, rather than the Tesla approach of building a convenient network statewide to get people like me from a major urban area to a vacation destination.

I hope the audit and ensuing action means that critical corridors like the one to Monterey get the fast-chargers they need to encourage people to buy EVs. Otherwise, even with range improvements, EVs will largely be doomed to commuter status for the foreseeable future, requiring people to buy gas cars for destination trips.

Tesla’s big announcement that the company is entering the standalone battery market for building owners and utilities got a lot of press and favorable Wall Street reaction. For longtime energy observers, Elon Musk wasn’t unveiling anything new — just repackaging something familiar and making it cool. But that repackaging and investment could be transformative.

The advantages to consumers that Tesla cites are well-established but probably not widely applicable. Some consumers can make a bit of money storing cheap energy and dispatching it at more expensive times under time-of-use rates. Big industrial customers may even save a lot of money this way. Other customers may like the clean backup power from batteries, although generators may be cheaper. And batteries could enable a few customers to go off-grid completely (really just for rural customers). There are already companies establishing themselves in this market, like Stem and Advanced Microgrid Solutions (which is partnering with Tesla on this effort).

Still, I can’t help but be taken by the cool factor that Elon Musk bestows on this otherwise geeky world. Just take the name: “Powerwall.” “Home battery” sounds so boring compared to having a Powerwall. And then there’s the sleek design with the Tesla logo:

Some people may pay $3500 just for the aesthetics — like a piece of garage art.

The other interesting piece is the price. At $3500 for 10kWh and $3000 for 7kWh, it looks like the estimates of a $300/kwh battery production cost may be accurate, which is a good sign for battery price decreases (prices were at about $1000kwh a few years ago). That price doesn’t include installation or the inverter.

Still, that’s not a bad deal, and if California ends up bolstering time-of-use rates, customers could soon get quicker repayment as the difference between cheap off-peak electricity and expensive peak rates increases.

The other wildcard here is repurposed batteries. Could Tesla end up taking used electric vehicle batteries and repurposing them for the Powerwall? Their future gigafactory could probably handle that workload well, further driving the price down of stationary batteries.

All told, the unveiling of Tesla Energy, while not revolutionary right now, could soon become the lead in a technology wave that fundamentally changes our energy system. As with so many clean technologies in this fast-changing field, we’ll have to stay tuned to find out.

The former Veep and Inconvenient Truther teamed up with a Tea Party firebrand against utility policies to roll back rooftop solar incentives:

The former Veep and Inconvenient Truther teamed up with a Tea Party firebrand against utility policies to roll back rooftop solar incentives:

In back-to-back speeches, the political Odd Couple struck surprisingly similar tones on clean energy’s future, even if Gore dwelled on renewables’ role in avoiding catastrophic global warming while Dooley didn’t use the words “climate change” at all, focusing on consumer choice.

“This is a battle that we will win,” said Dooley, a board member of the National Tea Party Patriots group. “I am literally floored with the response I have been getting from conservatives with the right message.”

Tea Party leaders of course never mention the words “climate change” because it “shuts down” the conversation. But solar means freedom and independence for many Tea Party conservatives, which is an important message for solar advocates to drive home.

Ultimately, political inroads among conservatives on issues like renewables will be necessary to build support for the broader policies needed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Let’s see if this movement will translate to Tea Party support for electric vehicles, energy storage and energy efficiency. Now that would really be an inconvenient truth — for climate deniers and the fossil fuel industry.

Brooke Crothers of Forbes investigates why electric vehicle sales seem to be taking off in his hometown urban Los Angeles, but not so much a mere 50 miles away in the high desert and other more rural areas of California.

He finds a few factors, such as lack of dealer interest in and knowledge of electric cars in more rural areas (they’d rather sell Silverados and Camaros). But it also may be the desirability of getting the carpool lane sticker for traffic-clogged commutes in the urban core.

I’m sure there are a bunch of factors at play, such as demographics, travel patterns, and the price and range of the vehicles. But my guess is that as new models of electrics come out (especially SUVs), as battery range increases to allow drivers in rural areas to easily access the nearby big cities, and as prices come down, this divide won’t quite be so stark.

Well, it was bound to happen. After hearing other EV drivers tell me their horror stories, I finally (sort of) got one of my own.

On Wednesday last week, I parked my Nissan LEAF at an off-site airport parking lot for a four-day trip, returning Sunday evening. I was the sole adult with three children in tow and parked the car with about 70 percent of the battery remaining (more than enough to get back home). I loaded the luggage and kids onto the shuttle van, had a great trip, and returned to the car on Sunday evening. Everyone was ready to get home, have a quick, late dinner, and go to bed.

But lo and behold when I looked at the dashboard, the sign said “key not detected” and the battery was at only 20% capacity. The roughly 24 miles remaining was not enough for a 15-mile, mostly uphill trip home.

What happened? Evidently I had failed to turn the car off when I left it. And with no auto shut-off feature, the car battery slowly died over four days, presumably beeping for an undetected key that was in my pocket 400 miles away.

We weren’t going to make it home. Panic ensued. We had to find an available charger somewhere nearby as the battery quickly dwindled on the freeway. We finally located (via Plugshare.com) a ChargePoint Level 2 in a parking garage by an Amtrak station in Oakland’s Jack London Square. Thankfully one of the two parking spots/chargers was available when we pulled in.

Since I don’t have a ChargePoint membership, I had to call to activate the charger with my Visa. I was on hold for a few minutes, and after about 5 minutes I got it plugged in. Then I had to wait in an empty parking garage with three hungry and tired kids while the car slowly charged. I gave myself about 30 minutes, which I figured would be about an additional 10 miles or so — just enough to get home.

I unplugged after about 35 minutes to be safe and had 28% of the battery now. But it was still a white knuckle drive home as the dashboard said we had about 9 miles remaining when we were about 5 miles from home. It was not a pleasant way to end the trip.

Lessons learned? Of course I need to double-check that the car is actually turned off. But why did Nissan not include an auto shut-off feature? After a day left on with no key, I think it’s safe for the car to turn off automatically rather than draining the battery. I really hope Nissan fixes that problem. The car motor is silent and so it’s not always obvious that it’s been left on. And I’ve noticed that sometimes it’s easy to accidentally double-click the off button, which actually turns the car back on.

Still, all in all we were pretty lucky. We found a charger and everything worked out. With more charging stations deployed, this kind of situation will be easier to handle in the future. But it was an inconvenience that could have been avoided by Nissan, and not just by my being more careful. I surely will be in the future though.

There are a number of misconceptions about electric vehicles. Like the battery is toxic and the mining for battery materials is destructive, so the cars aren’t great for the environemt (not true — they have a comparatively minimal environmental footprint and the batteries can be recycled or repurposed).

There are a number of misconceptions about electric vehicles. Like the battery is toxic and the mining for battery materials is destructive, so the cars aren’t great for the environemt (not true — they have a comparatively minimal environmental footprint and the batteries can be recycled or repurposed).

Or these cars are just for bigshots and celebrities like Brad Pitt (not true — lots of cheap lease deals out there, and the Nissan LEAF is under $20,000 in California after incentives).

Or electricity is a dirty fuel, too, so you’re not really helping the environment by switching to it from gas.

Okay, that last one is actually partially true. In states that are heavily dependent on burning coal for electricity, you’re better off driving a hybrid, if all you care about is air pollution. But those are just about eight states in the upper plains, like North Dakota and Iowa. And it’s still good to drive an EV there, just not great. Meanwhile, everywhere else it’s an environmental slam-dunk.

But even better news: given the improved efficiency of the vehicles, with longer range and better technology, coupled with coal power being swapped out for natural gas plants and more renewables, the environmental equation for electric vehicles is getting better and better.

As Green Car Reports noted late last year, a recent Union of Concerned Scientists study has upgraded the numbers to show significant improvements across the country. In states like California, EVs get the equivalent of almost 100 miles per gallon, while in “bad” states with coal, the numbers are 35 to 39 miles per gallon and getting better.

So in a few years, as prices come down, more of us will be able to do that cross-country all-electric drive for cheap — and without environmental guilt.

Batteries are key to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. We simply can’t avert massive climate change without them. Why? They will power our vehicles, instead of gas. They will store surplus renewable power when the sun isn’t shining and the wind isn’t blowing. And they can allow neighborhoods to go “off grid” entirely via microgrids, with neighborhood battery packs capturing surplus renewable power generated on-site, and no more need for electric utilities.

But the problem has always been that batteries are too expensive.

Now a new study by Björn Nykvist & Måns Nilsson in the journal Nature Climate Change (subscription only) shows remarkable progress on price. Keep in mind that the magic number to make batteries cost-competitive and enable long-distance, cheap electric vehicle batteries is about $150 per kilowatt hour (kWh):

We show that industry-wide cost estimates declined by approximately 14% annually between 2007 and 2014, from above US$1,000 per kWh to around US$410 per kWh, and that the cost of battery packs used by market-leading BEV [battery electric vehicle] manufacturers are even lower, at US$300 per kWh, and has declined by 8% annually. Learning rate, the cost reduction following a cumulative doubling of production, is found to be between 6 and 9%, in line with earlier studies on vehicle battery technology. We reveal that the costs of Li-ion battery packs continue to decline and that the costs among market leaders are much lower than previously reported.

While this is a bit wonky sounding, it’s significant. We’re seeing solid price declines each year and getting closer to that magic number of $150/kWh. While it’s unlikely we’ll see a sudden, massive drop in prices like we did with solar, this pace should mean that in another decade or so, electric vehicles could be widespread and the norm. And then renewable power can truly decarbonize our electricity sector by coupling with cheap batteries.

But we must maintain the federal and state incentives for batteries that we currently have in place, and then we can slowly phase them out as we approach that magic number. Those incentives include federal investment tax credits, federal and state tax credits and cash rebates for electric vehicles, and various grant funding for demonstration battery projects.

Without those incentives, this progress could be arrested before it reaches that magic price number. But for the time being, we have real reason for hope.

Necessity breeds invention, and in the case of electric vehicle charging, it’s come from an unlikely source. Tony Williams was a fairly typical EV driver and advocate. But in the last few years he has become a serial entrepreneur, developing homemade charging products that have become commercial successes. And they have all sprung from his own needs as a driver.

He’s got a number of nifty inventions, especially for Toyota Rav4 EV drivers. But my favorite might be his extension cord idea. From a profile on Williams in Charged Electric Vehicles Magazine:

When you come to a charging spot it’s often blocked, or the last guy left his EV there, or you just can’t reach because your charge port is in the rear – like with the RAV4, BMW i3, Mercedes B-Class, and Tesla Model S,” said Williams. “The number-one problem with charge ports in the rear is when you pull into angled parking spots with a charger on the curb. Often, the cord will barely reach, or it won’t at all, and turning the car around to back it in on a busy street is nearly impossible.”

In these cases, Williams realized that a J1772 extension cord would be invaluable. So he created one, called it JLONG, and started selling it. It’s one of those products, like jumper cables or a spare tire, that when you need it, you really really need it. The unfortunate truth is that when a driver needs to charge away from home, the competition is not only other EVs, but also gas cars that want to use the charging spots for parking. The JLONG helps to satisfy this really basic need. “I’ve seen some really nutty stuff out there with people stretching cords to the limit,” said Williams.

Like other states, California has a shortage of public EV charging stations and a problem ensuring that they are properly maintained and available for us when drivers need them. The extension cords could provide an easy way to increase their availability by allowing people to charge when another car is blocking the spot and either isn’t electric or is already charged.

As Williams relates, “It saved my bacon quite a few times, and I’ve heard a lot of similar stories from our customers. We sell quite a few of them.” The “JLONG” comes in customizable lengths but may soon be standardized to meet high-volume demand. For his part, Williams carries a 40 foot version.

It’s nice to see this kind of grassroots innovation take hold — signs that the electric vehicle market is here to stay and launching market-reinforcing products and services.