It was a rare defeat yesterday for California’s environmental community. After major victories in 2006 with AB 32 (to reduce greenhouse gases to 1990 levels by 2020), 2008 with SB 375 (to reform transportation and land use planning), and in 2010 with a voter rejection of the oil industry’s attempt to roll back AB 32 (Prop 23), climate advocates were getting comfortable in the Golden State.

But the Western States Petroleum Association (aka “Big Oil”) trotted out a well-funded and dishonest ad campaign targeted at “moderate” Assembly Democrats, who gutted a provision of SB 350 that would have legislated a goal to reduce petroleum use in California by half by 2030.

So is this a major setback for the environment and public health in California? Well, maybe not. If the Assembly passes and the governor signs SB 32, the state’s effort to continue the progress on AB 32 out to 2030 and 2050, the California Air Resources Board could essentially require the same petroleum reduction goals through regulation. That agency would have broad authority to do so under SB 32, as it currently has under AB 32. Because transportation emissions are the largest wedge in the greenhouse gas emissions pie, the agency has to tackle petroleum fuels at some level to achieve the broader legislated goals.

So is this a major setback for the environment and public health in California? Well, maybe not. If the Assembly passes and the governor signs SB 32, the state’s effort to continue the progress on AB 32 out to 2030 and 2050, the California Air Resources Board could essentially require the same petroleum reduction goals through regulation. That agency would have broad authority to do so under SB 32, as it currently has under AB 32. Because transportation emissions are the largest wedge in the greenhouse gas emissions pie, the agency has to tackle petroleum fuels at some level to achieve the broader legislated goals.

And the state is already well on its way to achieving those goals anyway, thanks to federal fuel economy standards, improving electric vehicle technologies, and greater renewable biofuels deployment, as NRDC points out.

But the downside is real: having these goals legislated, as opposed to being in a regulatory form pursuant to a governor’s executive order, means they would have been more certain and fixed. Now a new administration could force changes to how the Air Resources Board regulates fuels, and Big Oil could use their influence during the regulatory process to water down or gut new rules. Plus, they can more easily turn to the courts to challenge regulations, resulting in delays and extra costs for the agency.

So it’s definitely a loss for the environmental community, but in the long run the path that California has to take is clear. Big Oil will see declining market share as vehicles become more efficient, people drive less, and as electric vehicles take hold. Their victory yesterday will probably be a temporary one.

I’ve been an advocate for letting electric utilities build electric vehicle charging stations for a while now. While nobody likes the ideas of regulated monopolies taking over a market, the fact is that private companies are not getting the job done, and there aren’t sufficient charging stations to meet growing demand and to enable longer-distance electric travel.

I’ve been an advocate for letting electric utilities build electric vehicle charging stations for a while now. While nobody likes the ideas of regulated monopolies taking over a market, the fact is that private companies are not getting the job done, and there aren’t sufficient charging stations to meet growing demand and to enable longer-distance electric travel.

So I’ve been following with interest Pacific Gas & Electric’s (PG&E) proposal to serve the 65,000 EV drivers in its Northern California service territory with 25,100 charging stations (the number that may be necessary to meet Governor Brown’s goal of having one million EVs on the road by 2020).

But the California Public Utilities Commission would like to go slower than that, as Charged EVs reports:

[T]he state Public Utilities Commission has put a stop to PG&E’s dreams of empire for the moment, saying that it will need to hold a series of hearings before authorizing the program.

“We must consider the requirement to protect against unfair competition and the demonstrated costs and benefits of any utility electric vehicle charging station proposal,” PUC Commissioner Carla Peterman wrote in her ruling (via San Jose Mercury News). “We find that a more measured approach to utility ownership in PG&E’s service territory is warranted.”

One objection to PG&E’s plan is the cost: $654 million, which the utility plans to pass on to ratepayers. Under the original PG&E proposal, residential electricity customers would pay an additional 70 cents per month on their utility bills from 2018 to 2022.

Peterman also pointed out concerns that control of such a comprehensive network could give PG&E something of a monopoly. The utility’s plan calls for it to have control over the design and support of the charging facilities, something that other companies in the charging industry say could suppress innovation.

I think this approach could make sense. It may be best to go slow on the roll out to see how the market reacts. The CPUC could also ensure that the initial utility stations are located where there is no strong market incentive for private companies to site them. Ideally the state could end up with a hybrid system of some utility-owned stations and some private company-owned ones. The other possibility is that PG&E provides some of the underlying infrastructure for the stations, while charging companies then compete to set up chargers in those locations.

Either way, I imagine this is only the first step on a path to more utility-owned charging stations, and the result will hopefully be better coverage and convenience for EV drivers.

A lot of people are understandably wary about being early adopters of new technology. For the privilege, buyers often have to pay more and deal with unexpected problems. In the case of electric vehicles, the dynamic is the same, with many consumers worried about how long the batteries will last and what it will cost to replace them.

A lot of people are understandably wary about being early adopters of new technology. For the privilege, buyers often have to pay more and deal with unexpected problems. In the case of electric vehicles, the dynamic is the same, with many consumers worried about how long the batteries will last and what it will cost to replace them.

It’s hard to blame them. Reports from buyers of the first Nissan LEAF indicate that some batteries are failing pretty rapidly, sparking a class-action lawsuit. And some dealers of the Chevy Volt are quoting a whopping $34,000 for a full “drive motor battery replacement,” as Autoblog reports. Tesla, meanwhile, just unveiled a $29,000 replacement battery for their Roadster model, promising an additional 75 miles of range or so.

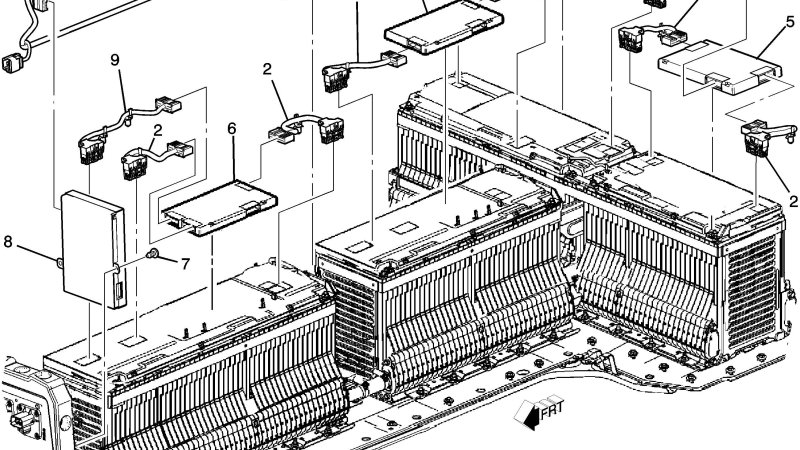

Autoblog performed a comprehensive look at what it might take to replace or repair a bad Chevy Volt battery, and the results are encouraging. For starters, after looking at the individual parts, the website found that while all three modules that make up the Volt battery add up to a fairly large $11,121.66 total, in most cases these battery cell modules do not need to be replaced:

There are many other individual pieces mounted on the battery pack that are serviceable, such as the Battery Energy Control Modules (BECM) and the Battery Interface Control Modules (BICM). These modules control and monitor the battery packs and charging system and have been known to fail while the lithium-ion battery cells are not at fault. Some have been replaced under warranty, but if you are stuck buying one they run about $255 a piece for the part. Getting a module replaced will cost you around $2,100 for parts, labor, and programming; labor can be a big hit since dropping the battery pack is required in order to service these modules.

If you are looking to replace the entire pack, the outlook has gotten better based on recent reports of refurbished battery packs becoming available for around $4,000. In these cases your entire battery pack is exchanged for one that comes from a refurbishing facility. These facilities do not produce any new parts but instead take packs that come in on exchange and combine the harvested pieces that are within spec from multiple packs to assemble refurbished packs.

Not bad prices if it buys you another 6-8 years of low-cost electric driving. The site includes a handy chart showing all the battery pack components:

Bottom line: fear of battery repair or replacement may not be such a big issue, particularly as we get more experience dealing with these used batteries coming out of the vehicles. Not to mention that there could and should be a robust market for buying these inexpensive used batteries, which would offer tremendous benefits for cleaning the grid and saving ratepayers money.

Electric vehicles as a clean technology movement have been in a holding pattern of late, if not a downright spiral. Sales are generally down from last year, battered by cheap gas prices and a lack of new models to excite consumers. Without advancements in the models, the broader consumer base is either unaware of EV benefits or cowed by perceived deficiencies (cost and range, mainly) of current EV options.

But that dynamic, I believe, is about to change.

New models are set to hit the roads this fall and winter that will likely start a new wave of EV buying. Most prominently, Tesla is finally talking to customers about designs for the new electric SUV, the Model X, set to release in limited production this month. The falcon-winged bad boy starts north of $130,000 though for the premium model, so sales will once again be aimed at the top 1% of us.

Chevy’s new Volt will also arrive this fall, complete with a marketing blitz. Early reviews sound positive, as the car looks better, drives longer on the battery (over 50 miles), and gets better gas mileage the few times you actually need it. Not to mention the new Nissan LEAF should be out soon, with possibly 120-mile range — a significant boost from the current 85-mile range.

When you add it up, the major EV automakers are set to introduce major upgrades to their products. While it’s harder to compete with cheap gas, EVs offer inherent benefits of a better and cleaner drive, lower maintenance costs, and the ability to drive for virtually free if you have solar PV on your roof. Plus, it’s the most important thing you can do for the environment if you have to drive.

So my guess is we’re in a holding pattern before some good news comes out on EV deployment. EVs won’t get to mass-market level for maybe another decade or so, but we’re getting there in big leaps, and this fall we should start to see another one take shape.

Well, it doesn’t take a brain surgeon to figure out which industries stand to lose if California transitions to a low-carbon economy. Judging by the latest attacks on SB 350 and SB 32, sprawl developers and the oil industry are feeling a little panicked.

First oil. They sent out a deliberately misleading mailer claiming that SB 350, which seeks to reduce California’s oil consumption in half by 2030, will lead to gas shortages and higher prices. Under the fake pro-consumer-sounding group the California Drivers Alliance, they claim the following:

The Gas Restriction Act of 2015 (SB350) will restrict the use of gas and diesel by 50 percent. This law will limit how often we can drive our own cars. The state will also be collecting and monitoring our personal driving habits and tracking how much gas we use. They’re now reviewing regulations to force automakers to include data monitoring systems in all cars so that regulators will be able to penalize and fine us if we drive too much or use too much gas.

The Sacramento Bee then shot this lying fish in its barrel with a fact check:

The ad exploits a lack of specificity in Senate Bill 350 about what measures the California Air Resources Board could take to reduce petroleum use. But it misleads by suggesting gas rationing, surcharges and citations based on driving habits are in store.

Bottom line: California will be pursuing fuel economy measures, electric vehicles, hydrogen fuel cells and biofuels to meet these objectives — not gas rationing. With battery costs declining, battery electrics should be the dominant vehicles in production by then anyway.

Next comes big sprawl in the guise of the Building Industry Association. The BIA claims SB 32, to extend our greenhouse gas reduction goals to 2030 and 2050, will be an automatic “zero net energy” mandate, leading to an additional $58,000 in costs for each new housing unit, or a price increase of over 12 percent.

However, these numbers once again mislead. First off, the bill is no such mandate for new construction. The California Energy Commission will continue to develop new ways to reduce pollution from new buildings, but it will be on the same trajectory it’s been on for decades, which has saved Californians billions since the 1970s.

Second, most of the costs the BIA tallies are attributed to oversized, expensive solar PV arrays for each new home. Even if all new buildings had to have those arrays (which they don’t), prices will come down by 2030 significantly (80% in the last five years or so), while most neighborhoods would likely pool together on community solar rather than purchasing it individually. Finally, any increase in efficiency measures and solar will only save California residents in reduced energy bills.

For more on the BIA arguments, NRDC has a nice take-down here.

I guess it’s good news these industries are fighting back. If we have any hope of a cleaner, more prosperous and sustainable economy, it will only happen if these industries go the way of the fossils they help burn.

A report from the Australian Renewable Energy Agency this month indicates it’s likely:

The 130-page report prepared by AECOM predicts a “mega-shift” to energy storage adoption, driven by demand – from both the supply side, as networks work to adapt to increasing distributed and renewable energy capacity, and from consumers wishing to store their solar energy – and by the rapidly changing economic proposition; a proposition, the report says, that will see the costs of lithium-ion batteries fall by 60 per cent in less than five years, and by 40 per cent for flow batteries.

This projection is more bullish than most analyses I’ve seen, which suggest price declines of 8-10% a year. If true, the impact on both our energy and transportation system will be enormous. Cheap batteries paired with solar will lead to customer “grid defections” from utilities, plus a proliferation of microgrids that can run independent of the grid. And of course electric vehicles will become ubiquitous with the cheaper price and better range.

Another reminder that batteries are the most critical clean technology right now in the effort to decarbonize our economy.

You can see a preview of the concept car, due hopefully by 2017, in this video:

I have to admit, the design doesn’t grab me. Why can’t EVs look cool instead of like strange insect cars? Tesla certainly pulled it off, and other models aren’t bad, like the Fiat or Chevy Spark. But the LEAF, Mitsubishi iMiev, and BMW i3 all look odd to me.

Still, this version seems to have some nice features, like plenty of interior room, lots of light, and some cool-looking seats. Nissan and Tesla will be competing with Chevy in this price and battery range, and those models can’t come soon enough. 2017 could be a turning point year for EVs.

The San Francisco Chronicle reports on the trend so far with the Tesla resale market:

An analysis of used Model S sales finds that while not many have hit the market so far — just 1,600 — they typically command prices well above $50,000. At the same time, they’re attracting buyers who are a little younger, a little less affluent and less likely to live in California than the typical Tesla driver.

“The way we think of the new Model S buyer is a wealthy tech executive living in the Bay Area — that’s the image in pop culture,” said Jessica Caldwell, director of industry analysis for the Edmunds.com auto information service. “If you have a lower price point, you’re going to get a larger, more diverse pool of people.”

Used EVs, including Teslas but also LEAFs and other models, will be cheaper and help to reach a much larger market. But they will also compete with cheaper, better-range vehicles that will be coming on-line in the next few years. Still, it will be hard to beat a cheap 200-mile used Tesla Model S for the foreseeable future.

Green Car Reports documents the challenges that drivers of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles are having finding functional stations:

Last year, the state of California committed $100 million over five years to building 100 hydrogen fueling stations in the state by 2020, in partnership with Toyota, Hyundai, and Honda, and private companies like First Element Fuel as well.

Early lessee Paul Berkman of Corona del Mar, for one, is frustrated.

He’s paying $500 a month for a vehicle he hasn’t been able to drive for five weeks, because all three hydrogen stations within 20 minutes of his home or workplace have been down for more than a month.

Berkman told Green Car Reports that the closest station, five minutes away at a Shell site in Newport Beach, has been “struggling”–and that at best it can only fill his Tucson Fuel Cell to half capacity.

Ten minutes away, a station by the University of California–Irvine campus has been closed for upgrades.

The California Air Resources Board issued a testy response to the article, which Green Car Reports included in an update. They cite the early trouble with plug-in electric vehicle stations, too, as an example of what they hope are just short-term problems.

Trouble is, public charging stations for battery electrics are also unreliable, even after a number of years of widespread usage. So that’s not exactly confidence-inspiring. The state will need to get this issue fixed, for both fuel cell and battery electrics, if it has any hope of encouraging widespread adoption of these technologies. But at least with battery electrics, you can just charge at home.

Barry Ritholz at Bloomberg seems to think that Tesla just put the nail in the long-term coffin of the internal combustion engine:

What Tesla has done with its “Ludicrous mode” upgrade for the Model S is figure out how to put almost all of the power in its system to all four wheels at once without melting its engine-management components.

The Tesla P85D with the complete 90kWh “ludicrous” upgrade costs about $100,000. The upgrade gives it a 0 to 60 mph time of 2.8 seconds. To put that into context, to get that sort of acceleration from a car previously required a Porsche 918 Spyder (0 to 60 in 2.3 seconds) or a Bugatti Veyron (2.6 seconds) or a Koenigsegg One (2.5 seconds). They each cost $1.1 million, $2.9 million and $3.8 million, respectively.

You can save some money by buying a Lamborghini Huracan ($237,250) or the Ferrari 458 Italia ($239,340), but both are slower than the Tesla. That makes the McLaren 570s a relative bargain at $184,900, but it, too, is slower than the Tesla.

The bottom line for Ritholz, who proclaims himself one not to make bold predictions, is that the top-end market will soon fall to Tesla, followed by the rest of the car market:

My guess is that by 2035, if not sooner, the majority of automobiles sold in the U.S. and Europe will no longer be gasoline-powered.

Let’s hope he’s right, because the future of climate stabilization depends on it.