It’s looking pretty fair to expect some big things from the Chevy Bolt EV, the first mass-market electric vehicle due out later this year.

Road Show’s editor-in-chief drove a pre-production Bolt from Monterey to Santa Barbara and reviewed it by video along the way. For those keeping score, that’s 240 miles on a single charge. It’s worth watching the video in full:

It’s looking more and more like Tesla just got scooped big time by Chevy on the mass-market EV.

But it’s also worth noting that Chevy has some serious advantages over Tesla. In addition to the production scale that Chevy can achieve in-house, it has the ironic advantage of selling a lot of dirty cars. The New York Times has a fascinating account of how Chevy beat out Tesla, and they cite this advantage:

Finally, G.M. enjoys the regulatory advantage of producing a fleet. Because the high-mileage, zero-emission Bolt helps the company stay under the federal government’s fuel-economy standards, it perversely allows G.M. to keep selling more profitable, gas-guzzling cars, like the Tahoe S.U.V. As a result, G.M. could lose money on each Bolt and still find the overall project valuable to its bottom line.

Tesla may benefit from a lot of zero emission vehicle credits from other automakers, but this regulatory quirk of fleet average emissions certainly benefits big automakers like Chevy over cleaner companies like Tesla.

But in the end, the more mass-market EVs on the road, the better — for both the consumer and the environment.

Tesla has all the hype and fandom, but Chevy is on pace to actually get it done. The “it” in question is developing a 200-mile range electric vehicle for under $40,000. The higher-mile range at that price is an important threshold for convincing average drivers to go electric with their next purchase.

The Chevy Bolt will feature a 60 kwh battery, and most people assumed that meant a range close to 200 miles, like Tesla’s Model 3. But Chevy just announced the vehicle will in fact have a rated range of 238 miles, compared to the Model 3’s 215 mile rated range.

And even more importantly, the vehicle will be on sale at the end of this year, compared to next year for the Model 3 (if that — given past history of delays, I would expect Tesla to deliver the vehicles in 2018, more likely).

To be sure, the Bolt won’t have a lot of the pizzazz of the Model 3, but it looks to be a solid car that could finally meet most, if not all, of people’s driving needs. Particularly with fast-chargers being deployed at a more rapid clip for long-range trips.

More importantly, it will help solidify consumer demand and industry commitment to driving electric. The future for this technology is bright, and I look forward to a day where air pollution from petroleum-fueled vehicles is a thing of the past.

Maybe some hard-core transit boosters don’t like electric passenger vehicles, but they should sure like battery electric buses. These EV buses cost less over time and don’t spew pollution when they accelerate.

Maybe some hard-core transit boosters don’t like electric passenger vehicles, but they should sure like battery electric buses. These EV buses cost less over time and don’t spew pollution when they accelerate.

Charged EV magazine interviewed two leaders of the industry, Proterra’s Ryan Popple and ABB’s Daan Nap. I’ve worked a bit with Ryan Popple in the past and am impressed with his understanding of the technology and ambitions for the future. I recommend reading his interview in full. Here’s a key snippet:

I also predict that, for a lot of these huge orders you see for 500 or 800 diesel buses that include long-term options to buy more, those options are not going to get exercised. They’ll probably ship the first third of that order, and then the transit authority board, the city’s mayor, or even the transit staff are going to insist that they don’t exercise the remainder of the options of the contract. This is because the backlash against fossil fuel is really building from an economic perspective. As you run the numbers on how much money they’re going to waste by deploying 500 diesel hybrids instead of EVs, you’re going to have taxpayer watchdogs start to come out of the woodwork and say, “This is crazy!” The reason it’s still happening is because EV tech is still relatively young and we have to prove it out. So we’re currently proving that we’re not equal to diesel, we’re better.

There will also be environmental and social justice pressures. How do you deploy 25 zero-emission buses in one part of the city, and then continue to emit diesel fumes on all the other bus routes? There is a fairness aspect to that. I think that, in time, the neighborhood that is next to the one with EVs will ask, “When are you going to stop making me breathe diesel exhaust? If it’s cheaper to run EVs in the city, when are we going to get them in my neighborhood?”

That’s why we’re starting to see those roadmaps to go all-electric from transit agencies. They want to communicate the plan to the communities that are asking these questions.

He also talks about the need to make EV bus charging standardized and competitive, as opposed to Tesla’s approach of vertically integrating the charging by owning it and making it incompatible with other vehicles. Of course, it’s different for Tesla when their market is largely private consumers. ProTerra, on the other hand, has to please municipal transit managers who don’t want to be held captive to one particular company with a closed-source charging technology.

The bottom line: as transit agencies get more experience operating these buses, and as prices continue to fall while manufacturing increases, the diesel exhaust-spewing bus will quickly become a thing of the past. That’s a development that both the pro-transit and pro-EV communities will both celebrate.

I’ve been a complainer about the lack of fast-charging sites on major interstate corridors in California. But perhaps just in time for any electric road trips this holiday weekend, I looked at the Plugshare map of the state today and was pleasantly surprised.

California has actually done a decent job getting more of these fast-chargers installed for long-distance trips (Tesla is excluded from this discussion since they already have a ton of interstate fast chargers deployed for their customers).

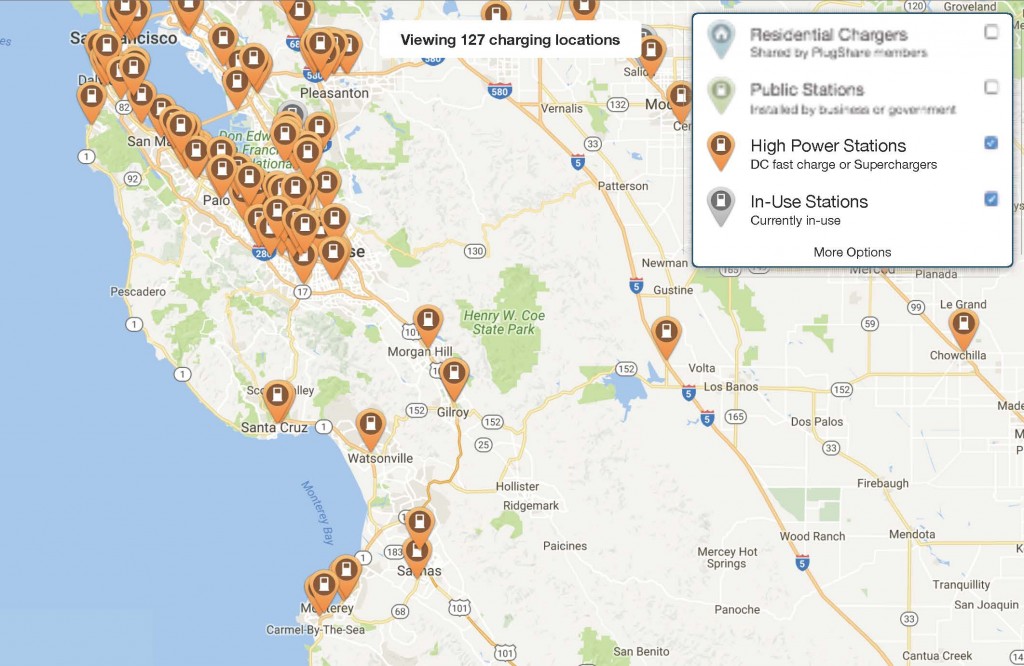

Here’s a map of the Bay Area to Monterey route, for example, which was impenetrable to most limited-range EVs until recently:

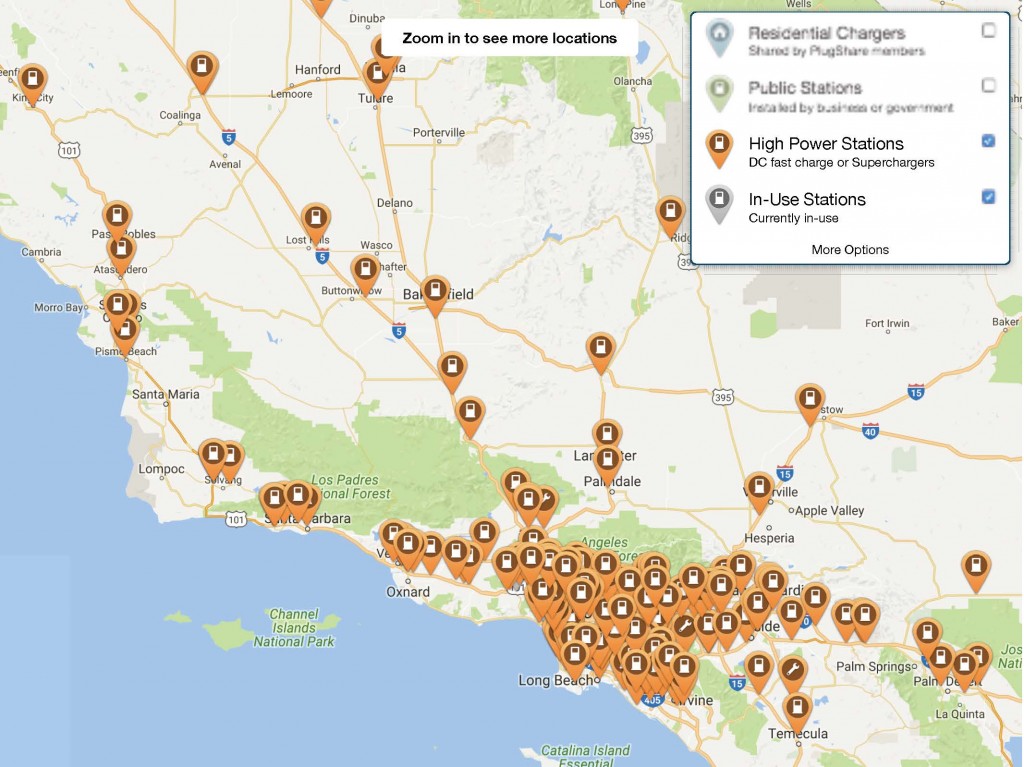

And here’s Interstate 5 towards Los Angeles (some of these are Tesla chargers though):

And here’s Interstate 5 towards Los Angeles (some of these are Tesla chargers though):

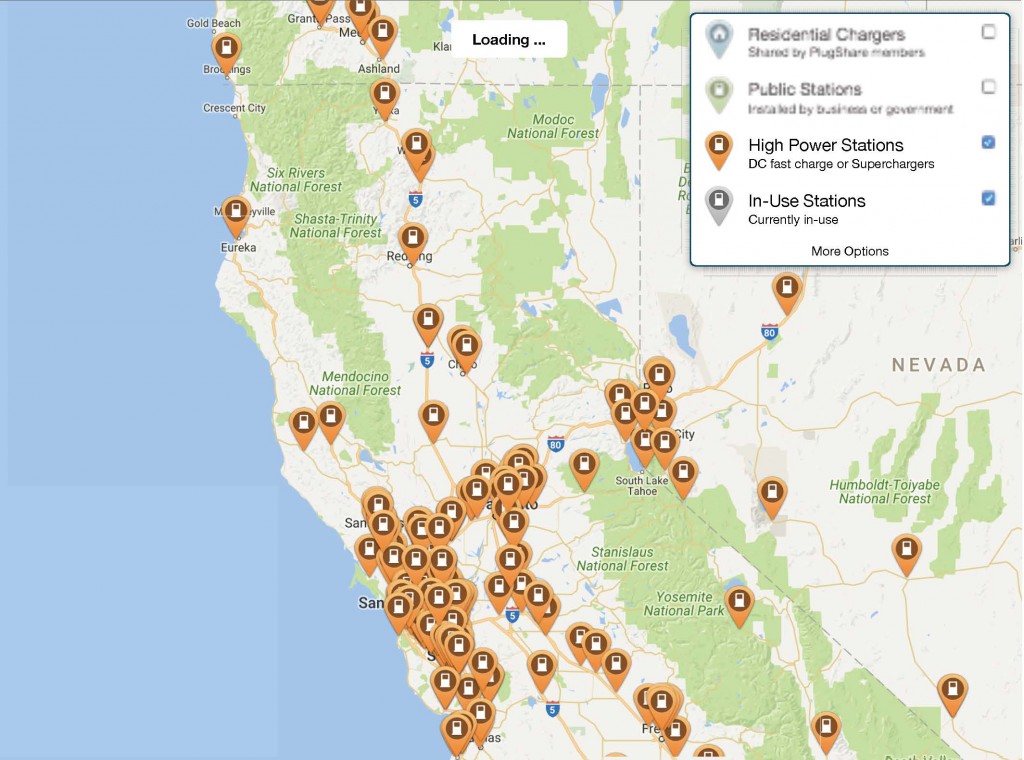

And then here’s I-5 north towards Ashland, Oregon:

And then here’s I-5 north towards Ashland, Oregon:

There’s still a ways to go, but many of these stations are new in the past year. It will be important to get even more charging infrastructure deployed as EV sales continue to rise with lower-cost, higher-range vehicles coming on the market.

There’s still a ways to go, but many of these stations are new in the past year. It will be important to get even more charging infrastructure deployed as EV sales continue to rise with lower-cost, higher-range vehicles coming on the market.

So happy Labor Day weekend, whether you’re driving electric or biking, walking, taking transit, or just staying put!

California leads the nation in plug-in electric vehicle sales, with about 40% of the nationwide total happening in the Golden State. While some of that progress is related to the sheer market size here, much of it is due to state policies. And the biggest of those policies is the “zero emission vehicle” (or “ZEV”) mandate, which the California Air Resources Board first adopted by regulation in 1990 under its Clean Air Act authority.

The program has been modified over the years but essentially requires automakers to sell a certain amount of “clean” vehicles (plug-in hybrids, battery electrics, and fuel cells), based on their total sales, or else they have to purchase credits for an equivalent amount. The goal is to achieve 15 percent of new vehicle sales from these “clean” versions by 2025, up from the current 3 percent market share, where it’s been stuck 2014.

The program has been modified over the years but essentially requires automakers to sell a certain amount of “clean” vehicles (plug-in hybrids, battery electrics, and fuel cells), based on their total sales, or else they have to purchase credits for an equivalent amount. The goal is to achieve 15 percent of new vehicle sales from these “clean” versions by 2025, up from the current 3 percent market share, where it’s been stuck 2014.

But here’s the problem: the credit system has generated a glut. As a result, many automakers now have no incentive to actually produce and sell more electric vehicles. And with recent weak demand for electric vehicles (due in part to low gas prices), they argue that they’d rather stockpile credits than make new vehicles.

It’s gotten under the skin of Tesla chief Elon Musk and his staff. Tesla benefits from the sale of credits to other automakers, and so the company suffers when the glut drives down prices and diminishes demand. Musk would like to see a higher threshold of credits needed to satisfy the requirement, which would just so happen to benefit Tesla’s bottom line.

It’s gotten personal among the automakers, per Reuters:

Earlier this month, Tesla’s Diarmuid O’Connell, vice president of business development, sparred with lobbyists for major automakers during a conference near Traverse City, Mich. He chided the industry for fielding electric cars that don’t sell because they are slow and have all the panache of household “appliances.”

John Bozzella, head of a group that represents several Asian and European auto makers, countered that most consumers don’t want electric vehicles – and pointedly wished Tesla well in its quest to achieve profitability.

The Board will be revising the program this December, so the issue has become a hot potato. NRDC released a recent study [PDF] of the current rules and progress to date, which documents that at this pace the state will fail to meet its deployment goals by 2025. They argue for tightened rules, such as a higher percentage of automaker sales that must be zero-emission through 2025, fewer credits awarded for each clean vehicle, and reduced credits that can be “banked” over time.

Clearly, changes like these need to happen with the program, because business-as-usual is not likely to get the electric vehicle market to the place it needs to be for long-term pollution reduction. To be sure, the market is making good strides, with the Tesla Model 3 and Chevy Bolt on their way. And the inevitable rise in gas prices will eventually help boost demand. But California cannot meet its long-term climate goals without widespread vehicle electrification, and a stronger ZEV program is key to making that happen.

Tesla is at it again, this time bumping their biggest battery pack size from 90 kilowatt hours up to the century threshold at 100 kwh. Why is this a big deal? It gives the Model S a range of over 300 miles now, which marks the first time an electric vehicle in production can get you that far on a single charge.

Or as Elon Musk says, you can now get from Los Angeles to San Francisco on a single charge (actually that’s dubious given the mountains, and at best would only get you to Los Angeles County, but still).

As an added bonus, the Tesla P100D is now the fastest car in production in the world, able to go 0 to 60 mph in 2.5 seconds (and third fastest ever).

But the range is the most noteworthy thing. Here we are in 2016, and you can have a 300-mile range electric car. Granted, the cost is prohibitive for all but the most wealthy, but prices are coming down steadily. It won’t be long, given current trends, before an electric vehicle could have a range of 600 or even 700 miles. And once the price comes down on those cars, maybe by the middle or end of the next decade, a lot of discussion about “range anxiety” and access to public charging infrastructure becomes largely moot.

The Tesla Model 3 got a lot of hype and pre-release deposits, but Chevy may quietly beat Tesla in bringing a 200-mile range electric vehicle under $40,000 to market. The new Bolt will supposedly be in production next year, and Car and Driver magazine just reviewed the prototype car with the Bolt’s chief engineer Josh Tavel:

Tavel is still tweaking various calibrations since Bolt production and sales are months out, but he’s clearly proud of what his development team has achieved. This 37-year-old engineer began amateur competition at age five on BMX bikes and continued with minimal interruption to his current SCCA Spec Racer Ford campaign. A deeply ingrained racing mentality may be why Tavel hated to sacrifice any torque to diminish tugs on the steering wheel, and why the Bolt’s every motion is well managed when you toss it around. Without imposing harshness, the ride is firm to help keep body roll in check during full-boogie maneuvers. The low-rolling-resistance Michelin Energy Saver A/S 215/50R-17 tires absorb patched pavement without recoil and break away gently when tasked with a surprise lane change.

The review is overall very positive, although it notes some of the flaws related to slow charging and driving experience, when compared to the new Tesla.

Still, at the right price and with dependability that Tesla may struggle to offer, this car could put electric vehicles on the map for average consumers in a big way.

Navigant’s William Tokash envisions the possibilities with the proposed SolarCity-Tesla merger:

Navigant’s William Tokash envisions the possibilities with the proposed SolarCity-Tesla merger:

A key aspect of technology innovation in renewable energy has been financing innovation. The development of power purchase agreement financing has been instrumental in the growth of solar PV. Navigant Research believes that financing innovation will also drive energy storage markets over time, as well. But the new Tesla could be uniquely positioned to apply financing innovation to an integrated solar battery PEV-based VPP [virtual power plant] while also providing consumers with the use of the vehicle. Imagine a homeowner entering into a 15-year financing agreement for solar, energy storage, and use of a Tesla Model 3 under a single contract. In this scenario, the new Tesla/utility partner manages the VPP asset while the customer gets access to, but not ownership of, a Tesla Model 3.

This financing arrangement could spark a real breakthrough in deploying more clean technologies. The issue for climate and clean tech, as Jigar Shah recently wrote to Bill Gates, is less about technology innovation at this point and more about how we actually start getting these technologies financed and built.

The proposed merger could get us farther down that road than we’ve been before, at least for home and business solar+storage, coupled with EVs in the garage.

Tesla’s master plan foresees electric buses but also autonomous, smaller mini-buses that can serve people on demand and take them right to where they want to go:

With the advent of autonomy, it will probably make sense to shrink the size of buses and transition the role of bus driver to that of fleet manager. Traffic congestion would improve due to increased passenger areal density by eliminating the center aisle and putting seats where there are currently entryways, and matching acceleration and braking to other vehicles, thus avoiding the inertial impedance to smooth traffic flow of traditional heavy buses. It would also take people all the way to their destination. Fixed summon buttons at existing bus stops would serve those who don’t have a phone.

This development is significant for two reasons. First, the push into the bus realm helps overcome some of the tension between electric vehicles and transit advocates. The electrification of transportation, as I’ve written before, reduces pollution from vehicles and also undermines the pro-transit argument that more buses and trains offsets pollution from gas-guzzling passenger vehicles. So if Tesla is improving transit vehicles, that gives anti-car, pro-transit advocates a reason to like the company.

Second, Tesla’s automated driving technology could greatly improve the service of transit. What bus user wouldn’t love transit on-demand that gets you right to where you want to go?

But some transit advocates aren’t buying it. Jarrett Walker at Human Transit thinks Musk’s vision will bump up against a “geometry problem”:

But when we get to dense cities, where big transit vehicles (including buses) are carrying significant ridership, Musk’s vision is a disaster. That’s because it takes lots of people out of big transit vehicles and puts them into small ones, which increases the total number of vehicles on the road at any time. The technical measure of this is Vehicle Miles (or Km) Travelled (VMT).

He bristles at the idea that technology boosters like Musk want to do away with the traditional fixed-route bus, which underpins mobility in dense urban environments.

But Walker never acknowledges that Musk does in fact address the “geometry” problem: automated mini-buses, in a world of all autonomous vehicles within dense city centers, will have the ability to “platoon” — essentially tailgate on steroids. Since the vehicles are all communicating with each other, they can drive bumper to bumper like train cars, freeing up a huge amount of street space.

Or as Musk writes, these mini-buses will be “matching acceleration and braking to other vehicles, thus avoiding the inertial impedance to smooth traffic flow of traditional heavy buses.”

I’m not an engineer, so I can’t say definitively that the gains in street space from platooning will offset the increase in vehicle traffic from mini-buses. But theoretically, it seems to me that we can achieve Musk’s vision and still have the dense urban environment and mobility of fixed-route buses, as Walker advocates.

All of this is still a ways off in the future, but not as far as many people might think. If Musk is correct on the timing, it could happen with the next decade. At that point, we may all be in electric vehicles, even if we live in a dense city and never drive a car.

I’m back from vacation, and while a lot has happened since I was away, the big story seems to be the unveiling of Tesla’s 2.0 master plan — at least on the environment and energy front. The key stand-outs for me are:

- The diversity of transportation modes that Tesla wants to electrify: It’s not just about passenger vehicles anymore, as Tesla wants to build buses and cargo trucks, too. And of course, the expansion into pickup trucks and compact SUVs are noteworthy.

- Autonomous driving will take a while: Musk writes that while the technology is being tested, regulatory policies are still way behind, especially taking into account all the jurisdictions around the globe. He anticipates another 5 years or so before fully autonomous vehicles are allowed everywhere.

- The big play on residential and commercial batteries for solar: the new acquisition of SolarCity has solidified this approach, but the master plan is clearly betting on solar incentives changing across the country. Right now it’s a pretty good deal to get rooftop solar in most places, but there are no incentives to capture surplus solar in a battery as long as customers are getting full retail credit from their utility for it. Musk seems to betting that retrenching these incentives, as Nevada and Hawaii have done, will become the norm and will therefor provide an opportunity for batteries. It could also set up Tesla as a bit of an opposition force to traditional solar installers in these state battles, as those companies generally don’t want solar incentives shifted to batteries.

I’ll have more thoughts soon in particular on the Tesla play for buses and transit. But in the meantime, Musk has given the public a lot to chew on.