The federal tax bill back in December spared the generous $7500 EV tax credit that a purchaser of an electric vehicle now receives. But not all the automakers are jumping for joy about it, particularly GM and Tesla. As the New York Times explained:

That’s because as now structured, the tax credit puts Tesla and G.M. at a competitive disadvantage, especially compared with foreign rivals who are just starting to ramp up electric vehicle sales in the United States. The tax credit begins to phase out after a company sells 200,000 electric vehicles — a threshold both Tesla and G.M. are expected to reach this year.

Meanwhile, buyers of electric BMWs, Volkswagens and Volvos will continue to get the full $7,500 credit. All of those manufacturers have announced aggressive sales plans for electric vehicles in the United States but so far have sold relatively few of them.

It now seems clear that limiting the taxes to 200,000 vehicles per automaker, as opposed to an industry-wide credit or one that expires for all companies by a date certain, will penalize EV pioneers like Nissan, GM and Tesla going forward. Their vehicles will soon be more expensive than competitors’ who waited to introduce their EVs until now and will therefore have customers who can take advantage of the tax credit for their company.

It’s already affecting customers who want to buy Tesla’s “mass market” Model 3. Many of them were hoping to get the cheaper version of the vehicle before the tax credit expires for the company, but Tesla is first introducing the more expensive version of the car with longer range. Customers who want the cheaper model will probably be out of luck by then, tax credit-wise.

It’s already affecting customers who want to buy Tesla’s “mass market” Model 3. Many of them were hoping to get the cheaper version of the vehicle before the tax credit expires for the company, but Tesla is first introducing the more expensive version of the car with longer range. Customers who want the cheaper model will probably be out of luck by then, tax credit-wise.

With Republicans in charge of congress, it’s unlikely they’ll change the current EV tax credit structure. But ideally it would be reformed to affect all companies equally, while phasing out over time to reflect the decreasing costs of producing the vehicles.

It’s commonly understood that the lack of electric vehicle charging stations is a significant barrier to consumer adoption. Whether you live in an apartment without a dedicated parking spot or a single-family home and need to charge quickly on longer road trips, the infrastructure availability can make or break decision-making.

But it’s less understood among even electric vehicle drivers themselves how complicated charging can be, in terms of the multiple formats and charging speeds. First, the good news: the U.S. now has 47,114 public EV charging outlets, up from 25,602 at the end of 2014, per the U.S. Department of Energy.

But here’s the problem, as E&E news covered [pay-walled]:

But they’re not all the same, and not all cars can use them all. Tesla Inc.’s Supercharger Network, for example, only works for Tesla drivers. Charging at home on a Level 1 or 2 charger can take all night; charging at a public fast-charging station can take 30 minutes or less, depending on the power provided and technology.

One of the key technology developments has been increasing the power — and speed — of the charging stations. Tesla’s Supercharger Network of 8,496 stations provides up to 120 kilowatts per car, but it is proprietary.

Other automakers have increased the capacity of their latest models, and an increasing number of stations are planning to deliver more than 100 kW, a change from the earlier 50 kW. ChargePoint Inc. has developed a 400-kW charging technology. EVgo, another charging company, is installing up to dozens of high-powered fast-charging stations of 145 to 350 kW. Automakers and technology startups have developed technology that would fully charge a car in five minutes or less, although it’s not yet widely available.

All these numbers can be confusing, and really people just want a simple answer to the question: how long will it take me to charge my battery? Here’s how I like to explain it to the average person:

- “Level 1” (or your standard wall outlet) will charge your car about 5 miles per hour. The formats are the same across all vehicles.

- “Level 2” (or 240 volts, like for a large home appliance) has more variability, but generally will give you about 20 miles per hour. The formats are also the same across all vehicles. But the variability in charging speed can be fairly significant, due to the divergent amperage (or “amps,” measuring essentially the volume of the electric current) allowed by various batteries and charging stations. Here are the three big examples of differing charging speeds just within Level 2:

- If you can only Level 2 charge at 16 amps, that’s total power of 3.8 kilowatts (you multiply 240 volts by amps for total power). At that speed, with a Chevy Bolt EV’s 60 kilowatt-hour battery, it would take you 15.8 hours to fully charge from zero (60 divided by 3.8). With 238 mile range, that equals 15 miles per hour.

- If the battery could accept 32 amps, that equals 7.6 kilowatts of power at the Level 2 charging station, which means the Chevy Bolt would charge fully from zero in 7.9 hours. That equals 30 miles per hour.

- And if your battery could accept 48 amps (like all Teslas do), you could fully charge at 11.5 kilowatts in 5.2 hours, or 45 miles per hour. So 5.2 hours to 15.8 hours is a huge range, just within Level 2.

- “Fast Charge” has the most variability and also three incompatible formats across North American/European, Asian and Tesla vehicles. As the article above mentioned, most fast chargers have 50 kilowatts of power. That means you could charge your Chevy Bolt EV in a bit over an hour (60 kilowatt hours divided by 50 kilowatts), although really less than that because the car is programmed to charge at a reduced speed for the last 80% to minimize harm to the battery. So I’d bank on about two hours, or 120 miles per hour, for a full charge from zero in a 50 kilowatt fast charger. Tesla fast-chargers are much quicker at 120 kilowatts, meaning your Chevy Bolt EV (which can’t use those chargers but just for the sake of calculation) could charge closer to 30 or 40 minutes, or 200 miles in 30 minutes (although slower given the last 20% slowdown I just mentioned). And at 350 kilowatts, you could charge your Chevy Bolt EV like you are at a gas station, in perhaps just 20 minutes.

So we need more 350 kilowatt chargers, and we need them all over major interstate corridors and in urban “plazas” for apartment dwellers. We covered some solutions for this deployment in the report Plugging Away last year.

And hopefully one day charging will be so simple and ubiquitous that nobody will need to bother with all the calculations and explanations I’ve offered here.

California Goes Green is a self-published 2017 book that provides an overview of California’s history of climate leadership, including some anecdotes on key policies and the leaders who helped develop and implement them. It was written by two longtime energy policy leaders with first-hand perspectives: Michael Peevey, former president of the California Public Utilities Commission and energy executive, and Diane Wittenberg, who has been involved in electric vehicle policies since the 1990s and in the utility world before that.

California Goes Green is a self-published 2017 book that provides an overview of California’s history of climate leadership, including some anecdotes on key policies and the leaders who helped develop and implement them. It was written by two longtime energy policy leaders with first-hand perspectives: Michael Peevey, former president of the California Public Utilities Commission and energy executive, and Diane Wittenberg, who has been involved in electric vehicle policies since the 1990s and in the utility world before that.

Peevey and Wittenburg are therefore well positioned to describe this history, and their book focuses largely on California’s efforts to decarbonize the electricity and transportation sectors. It touches on renewable energy, energy storage, energy efficiency, and electric vehicle policies, preceded by some general environmental and cultural history in the state.

Overall, California Goes Green provides a brisk (142 pages, including an epilogue) overview of why Californians care about the environment, dating back to battles to reduce smog in Los Angeles after World War II. The authors recount how the state’s culture and politics was shaped by the work of universities, business leaders, and policy advocacy organizations to bolster policy and technology responses to environmental challenges.

The highlights of the book include some interesting anecdotes on some of Peevey and Wittenberg’s topics of expertise, like the 2000-01 state energy crisis, the formation of major environmental agencies in the 1960s and 1970s, the ballot battle over the failed Prop 23 initiative to suspend California’s climate law in 2010, and California’s ultimately successful effort to obtain a federal waiver from the EPA under the Clean Air Act in the 2000s. We also learn some interesting historical tidbits, such as former Governor Schwarzenegger taking an interest in rooftop solar policies because his friend (and movie director) James Cameron had trouble getting approvals for his solar array and called on the governor for help.

But the book offers relatively superficial accounts of some of the most crucial policy battles. Although the authors acknowledge interviews and other communications with key figures involved, the narrative does not feature any direct quotes from those present. Nor do the authors explore in any meaningful depth the various interest group positions and concerns and compromises that went into some of the key policy deals.

There’s also the nagging feeling that the authors are overstating Peevey’s role in some of this history (although he clearly was a central figure on utility regulation and some other policy fronts for an important period of time). For example, at one point the book suggests that Peevey single-handedly was responsible for bringing to California the idea of installing smart meters, after a trip to a utility conference in Italy. But this sounds a bit far-fetched, given the longstanding and broad-based movement to bring smart grid technology to the U.S. But perhaps that’s an unavoidable drawback of having one of the players on the field write the history of the game.

The authors also represent the book as a guide for other jurisdictions and countries who want to follow California’s policy lead, and it should be helpful in that respect. But they don’t provide readers with a basic overview of what climate policies are needed in a developed economy at a macro scale, like a mini version of the state’s comprehensive scoping plan. As a result, the authors focus the book mostly on electricity and transportation but fail to cover in any real way key climate issues such as transportation infrastructure, land use and sprawl, and short-lived climate pollutants, just to name a few. These are all significant contributors to greenhouse gas emissions and merited more attention in the story.

Despite these shortcomings, the book is useful background for anyone working in climate policy or just wants to know more about California’s efforts to date. It also does a nice job giving credit to some relatively unheralded environmental leaders through various “profile” pages. But we still need a fuller story of how these and other leaders got these landmark policies adopted. These details would be both illuminating and entertaining to read for not just for policy wonks, but for the general public that would benefit from a comprehensive and accessible account of California’s pioneering efforts to combat change.

Countries like China, Norway and the U.K. have made headlines recently with plans to ban the sale of internal combustion engine passenger vehicles by 2040 or soon thereafter. Is California next?

Governor Brown expressed interest in the state following suit, to maintain its mantle as a global electric vehicle leader. And now Assemblymember Phil Ting (San Francisco) has introduced AB 1745 to ban registrations of new internal combustion engines by 2040.

As a legal matter, California probably won’t be able to enforce this ban without a waiver from the federal government under the Clean Air Act, which otherwise prevents states from issuing stronger tailpipe emissions standards than federal regulations. But that issue is a long way off.

So in the meantime, the bill would be a symbolic but also a practical signal to industry and state policymakers in various agencies that California is serious about phasing out fossil fuel use in passenger vehicles. And it would give the state direction to start laying the policy foundation to make this transition in a more aggressive way.

Fortunately, automakers are already moving in this direction, albeit tepidly. Part of the problem, as Bloomberg covered last month, is that forecasts for EV adoption are uncertain:

Electric cars—which today comprise only 1 percent of auto sales worldwide, and even less in the U.S.—will account for just 2.4 percent of U.S. demand and less than 10 percent globally by 2025, according to researcher LMC Automotive. But while consumer appetite slogs along, carmakers are still planning a tidal wave of battery-powered models that may find interested buyers few and far between.

It’s a bit of a chicken-and-egg problem, but no automaker wants to be caught flat-footed on what looks to be a potential revolution in transportation.

Meanwhile, the transition to zero-emission vehicles raises all sorts of policy questions, as the New York Times explored recently. The bottom line is that we’ll need more charging infrastructure and vastly reduced costs in batteries to make the vehicles ubiquitous. Part of that involves a more secure battery supply chain.

One point of disagreement with the Times piece though: the article claims people may be too attached to the feel and smell (!) of internal combustion engines to switch to electric. But for anyone who’s driven an electric vehicle and experienced its superior driving experience, this fear is almost laughable. The product is simply better than a gas engine.

Ting’s bill will benefit from that technological superiority and falling costs of batteries. But it will face some serious political headwinds from entrenched interests that benefit from gas-powered vehicles.

With a rough 2017 on the environment now in the books, here are the top issues I plan to follow in 2018 on climate change:

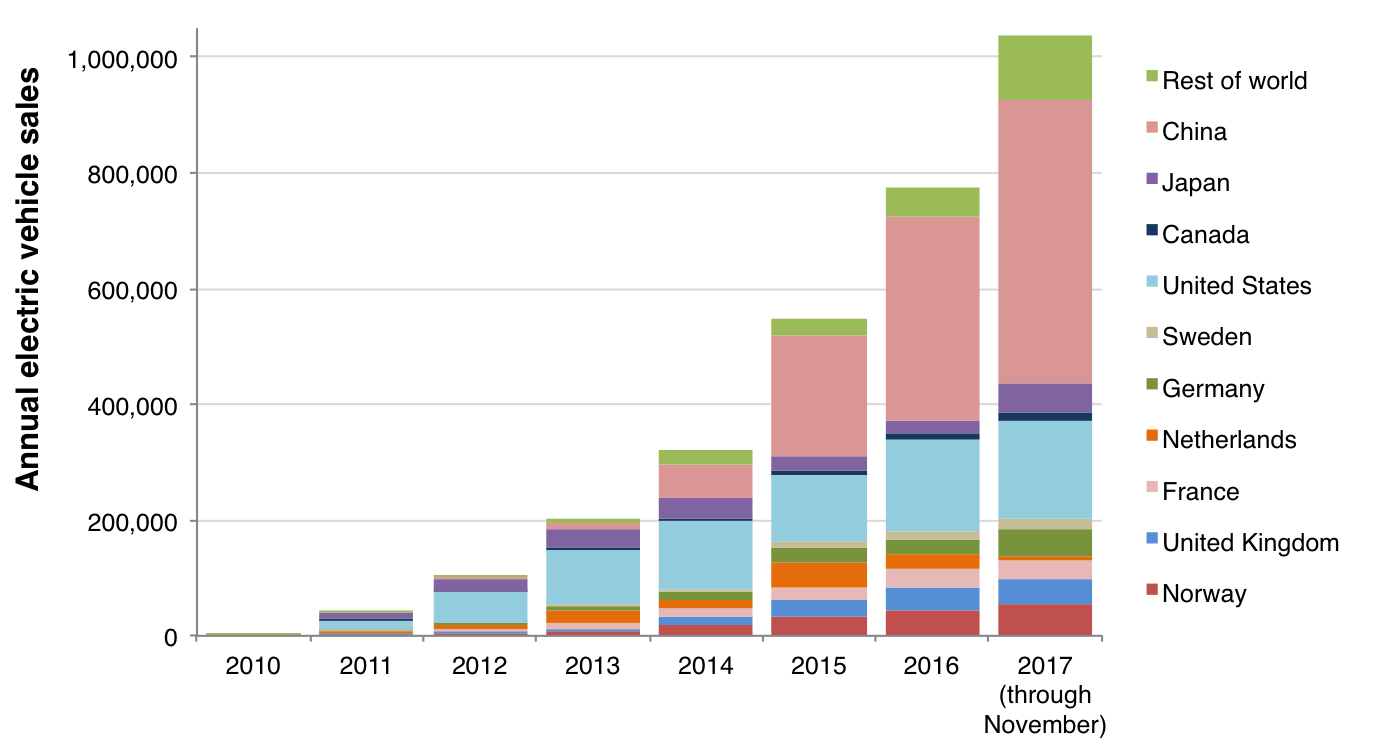

- A possible boost for electric vehicles from new models and global demand: With the more affordable Tesla Model 3 finally trickling out, plus aggressive EV policies in countries like China, hopefully we will see continued increases in demand for electric vehicles. Here’s an interesting chart on EV adoption worldwide, illustrating in particular the pivotal role that China is playing:

- Impacts of potential oil price increase: OPEC nations have already decided to cut oil production, which could mean that prices will increase with less supply (perhaps even despite more pumping from the U.S. and Russia). If oil prices rise, gas prices will go up, possibly leading to more demand for electric vehicles and other fuel-efficient vehicles and a decrease in pollution.

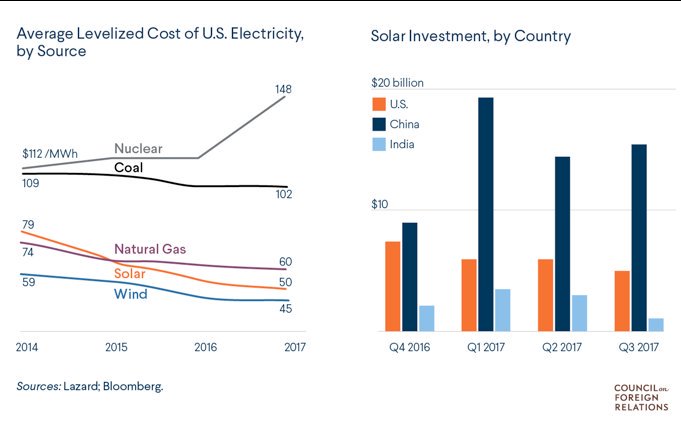

- Renewable energy’s political headwinds and tax uncertainty, coupled with falling costs: The Trump administration is doing everything it can to boost coal and undercut renewables (particularly with likely tariffs coming on foreign solar panels). And the 2017 federal tax legislation creates uncertainty for wind and solar tax credit financing going forward. But the economics of renewables continues to defy expectations. Here’s a chart with some more details on the rapid progress made in the past few years, including just in 2017:

- More extreme weather & environmental challenges: 2017 was a doozy on extreme weather, with another record-breaking temperature year that included brutal wildfires and hurricanes like we’ve never seen. As the climate continues to warm, expect more of these events, with the potential for them to change the politics around climate. Special mention: the impact of Puerto Rican refugees on Florida politics.

- U.S. state action to fill the federal void on climate leadership: States (and many cities) are continuing to move aggressively on climate. Will we see more states join California’s cap-and-trade program or implement strong greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets, including carbon taxes? Will we see multi-state collaborations on climate? This year could provide some opportunities for state gains on climate leadership, particularly in states like Oregon and Washington, plus the continued possibility a regional western-wide grid to facilitate renewable deployment across the western U.S.

- 2018 mid-term elections: A Democratic takeover of at least the House, if not the Senate, would dramatically change the prospects for climate policy in the country. A Democratic House means the purse strings could swing back in favor of funding environmental measures, plus some congressional oversight on agency action (or inaction or worse, in the case of climate change). A Democratic Senate could in turn mean much more moderate judicial nominees who hear cases on agency decision-making on the environment.

Honorable mention: California housing policy. While 2017 was supposed be the “Year of Housing,” much more work remains to be done. Will California legislators finally start to rein in local control over land use, which has prevented sufficient infill housing in thriving metropolises from getting built? And relatedly, will California voters overturn in November the state’s new gas tax increase, which helps fund transit and road repair to serve infill housing?

Lots of interesting issues to follow this year. Thanks for reading this blog — I look forward to covering them all and more in 2018.

Republicans from the House and Senate last week unveiled their compromise conference tax bill. Due to intense lobbying efforts, Republican negotiators seem to have reduced some of the harm I described for renewable energy, electric vehicles, and affordable housing. As Brad Plumer in the New York Times writes, support for renewables is now bipartisan, as Republican states like Iowa produce a lot of wind power, while states like Ohio and Nevada with Republican senators manufacture a lot of clean technology equipment.

Republicans from the House and Senate last week unveiled their compromise conference tax bill. Due to intense lobbying efforts, Republican negotiators seem to have reduced some of the harm I described for renewable energy, electric vehicles, and affordable housing. As Brad Plumer in the New York Times writes, support for renewables is now bipartisan, as Republican states like Iowa produce a lot of wind power, while states like Ohio and Nevada with Republican senators manufacture a lot of clean technology equipment.

Most of the changes in the bill involve corporate tax credits, which are used to finance renewables and affordable housing. First, the conference bill removes the corporate “alternative minimum tax,” which would have made tax credits essentially moot with corporations unable to reduce their taxes below a certain amount. Second, it minimizes the damage from a new provision called the Base Erosion Anti-Abuse Tax (BEAT), which seeks to prevent multinational companies from claiming a portion of production or investment credits. The conference bill allows the credits to offset up to 80 percent of the BEAT tax, which helps preserve the market for the credits among multinational companies (Utility Dive offers a good overview of the details of these provisions).

Wind power is still hurt by the bill, given that the new provisions do not cover the full duration of production tax credits that finance these projects. And by reducing corporate tax rates overall, the bill decreases corporate “tax appetite” that helps drive demand for the tax credits. But it could have been much worse.

Meanwhile, the conference bill continues the tax credit for electric vehicle purchases, which is set to phase out for each automaker anyway based on sales (but the bill reduces tax incentives for transit and biking). This credit has been very important to boosting demand, as University of California, Davis transportation researchers have documented.

Finally, on affordable housing and other infill projects, the draft legislation would preserve most of the tax credits used to finance these projects. It retains the low-income housing tax credits (LIHTC), continues tax-exempt private activity bonds, including multifamily bonds, which are used to finance all sorts of infill infrastructure, and saves the 20% historic tax credits. It also retains new markets tax credits and of course reduces the corporate tax rate to 21%, which presumably benefits many infill developers. You can read more on the provisions affecting housing and land use from Smart Growth America.

Presuming no new issues arise, votes on the compromise bill could come this week and possibly be signed into law before Christmas. Overall, it’s a bill that will add at least $1.5 trillion to the debt, starve government of funds to provide basic services and infrastructure, and mostly benefit the wealthy and large corporations at the expense of middle-income earners.

But for clean technology and housing at least, it went from devastating to just bad.

UPDATE: Initial reports that the electric vehicle tax credit was killed in the Senate version may have been inaccurate. The text of the amendment contained some obscure language that actually indicates that it was not adopted in the ultimate bill.

Donald Trump’s electoral college win a year ago certainly promised a lot of setbacks to the environmental movement. His administration’s attempts to roll back environmental protections, under-staffing of key agencies enforcing our environmental laws, as well as efforts to prop up dirty energy industries have all taken their toll this year.

However, until the tax bill passed the Senate this week, much of that damage was either relatively limited in scope or thwarted by the courts. But the new tax legislation now passed by both houses of Congress, and still in need of reconciliation and a further vote, could dramatically undercut a number of key environmental measures in ways we haven’t yet seen from this administration.

Originally, there was some hope that Republicans in the U.S. Senate would weaken some of the draconian environmental measures in the original House tax bill. But that was largely dashed by the late Friday night, partisan vote in the U.S. Senate. First, the bill targets clean technology while promoting dirty energy:

- The renewable energy tax credits for wind and solar are severely undercut by an obscure provision in the bill called Base Erosion and Anti-abuse Tax (BEAT), as Greentech Media reports. While analysts are still reviewing the provisions to discern the likely impact, initial assessments are that this bill language could greatly hurt the industry by decreasing the value of the credits.

- Similarly, the reinstatement of the alternative minimum tax for corporations, which was not in the House bill, also hurts the market for renewable tax credits, if not devastates it. By inserting this provision at the very last minute, Senate leaders attempted to offset some of the other tax cuts and projected deficits by ensuring corporations pay a minimum tax. The problem is that it renders many tax credits worthless, as businesses will no longer need them. Particularly hurt are wind energy projects, which rely on the production tax credit, as well as solar projects that rely on the investment tax credit.

- As a dirty cherry on top, the Senate bill opens the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil drilling.

On housing, the tax bill has the potential to devastate affordable housing. Affordable projects often rely on tax credits for financing. As Novogradac & Company writes, the BEAT provision will dampen corporate investors from claiming tax credits like the low-income housing tax credit (LIHTC), new markets tax credit (NMTC), and historic tax credit (HTC), all used to fund affordable and other infill projects. Other changes in the bill promise further dampening of financing for affordable housing.

The only good news for environmental and housing advocates is that there is still a chance to make changes in the bill through the conference committee. And that the provisions here can be rescinded in 2021 with a new congress and president.

California is on track to meet its 2020 climate change goals, to reduce emissions by that year back to 1990 levels. Much of that success is due to the economic recession back in 2008 and significant progress reducing emissions from the electricity sector, due to the growth in renewables.

But the state is lagging in one key respect: transportation emissions. Bloomberg reported on the emissions data compiled by the nonpartisan research institute Next 10:

But the state is lagging in one key respect: transportation emissions. Bloomberg reported on the emissions data compiled by the nonpartisan research institute Next 10:

In 2015, the most recent year for which data are available, the state’s greenhouse gas emissions dropped at less than half the rate of the previous year, according to an August report from the San Francisco-based nonprofit Next 10. Low gas prices and a lack of affordable housing prompted more driving and contributed to a 3.1 percent increase in exhaust from cars, buses, and trucks, the report says. Census data show that more than 635,000 California workers had commutes of 90 minutes or more in 2015, a 40 percent jump from 2010.

The solutions are urgent: we need to reduce driving miles by building all of our new housing (an estimated 180,000 units needed per year) near transit, and we need to electrify our existing vehicle fleet and add in biofuels and hydrogen where appropriate. Otherwise, the state will not be as successful in meeting its much more aggressive climate goals for 2030, with a 40% reduction below 1990 levels called for that year.

Last week I blogged about how electric vehicles (and consumer electronics) run on batteries with cobalt, too-often mined with child labor in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Congo is the world’s biggest producer of cobalt, with more than half of global supplies. And cobalt prices have skyrocketed recently with the growth of EVs.

But reports by Amnesty International point to the human rights risks. The group says that approximately one-fifth of Congo’s cobalt production is mined by hand by “informal miners,” including children, in dangerous conditions. Amnesty recently ranked 29 companies on how well they were tracking their cobalt sources since a January 2016 report spotlighted the issue. Reuters covered the results:

“Apple became the first company to publish the names of its cobalt suppliers … but other electronics brands have made alarmingly little progress,” the statement said.

Most cobalt is produced as a by-product of copper or nickel mining, but artisanal miners in southern Congo exploit deposits near the surface that are rich in cobalt.

The biggest buyer of ore from small-scale miners was Congo Dongfang Mining International, a wholly owned subsidiary of Chinese mineral giant Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt Ltd, Amnesty found in its report last year.

Since then, Huayou Cobalt “has taken a number of steps” in line with international standards but “gaps in information remain”, Amnesty said.

The group was particularly critical of Microsoft, which was among 26 companies that does not disclose their suppliers’ records on this issue, as well as Renault and Daimler among the automakers (BMW had made the most improvements). Microsoft responded to the criticism, arguing that it’s doing more than the report indicates to clean up and disclose its supply chain.

The Amnesty report shows the value of public pressure on this issue. While a global governance framework to ensure a stable and just supply of battery materials will likely be needed, it’s encouraging to know that old fashioned public pressure can help bring progress, too.

Last week I blogged about the potential environmental and governance harms from clean technology mineral extraction. But what about one specific technology, the lithium ion batteries powering the burgeoning electric vehicle market?

Alex Tilley and David Manley of Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) discussed the potential boom in lithium mining in specific parts of the globe:

[I]dentified lithium resources are concentrated in salt flats in Argentina, Bolivia and Chile. If the world shifts to lithium-ion batteries to power vehicles and electricity consumption, South America will become a globally strategic region for energy. And if governed well, this industry could be transformative for these countries’ economies.

Fortunately many of these lithium-rich countries have decent standards and processes for mineral extraction, although we’ll need to be vigilant to monitor impacts.

The story is more concerning though for cobalt, also an important metal for EV batteries. Cobalt is a byproduct of copper and nickel mining, and a typical EV contains about 33 pounds of cobalt. Until recently, there were often surplus cobalt supplies, as it was used mostly for steel production. But its ability to conduct electricity so efficiently has made it critical for rechargeable batteries like in EVs and therefore more in demand.

The problem is the location of the supply. Thomas Wilson in Bloomberg News tackled cobalt mining in a recent piece, noting that the relatively rare metal is found mostly in the Democratic Republic of Congo, “a country in the African tropics where there has never been a peaceful transition of power and child labor is still used in parts of the mining industry”:

The country formerly known as Zaire — which hosted boxers Muhammad Ali and George Foreman for their 1974 heavyweight title bout dubbed the “Rumble in the Jungle” — supplies 63 percent of the world’s cobalt. Congo’s market share may jump to 73 percent by 2025 as producers like Glencore Plc expand mines, according to Wood Mackenzie Ltd. By 2030, global demand could be 47 times more than it was last year, Bloomberg New Energy Finance estimates.

With demand growing, mining companies including Glencore, Eurasian Natural Resources Corp. and China Molybdenum Co. are pouring more money into Congo. With cobalt prices rising, that government is looking for ways to increase its control of the supply as well as the profits. It’s also creating supply disruptions, as in a recent incident in which the government blocked copper and cobalt exports by the China-Congo joint-venture Sicomines in a dispute over local refining.

Worse, the cobalt mining may entail significant human rights violations. Amnesty International alleges that some “informal” mines may rely on child labor.

Corporations are responding to some of the public pressure around situations like in Congo to address the human rights and environmental implications of the battery supply chain. Apple and Samsung in particular were forced to more fully vet their suppliers. But these companies don’t always know where their cobalt comes from. Ultimately, more than half of the world’s supply of refined cobalt in rechargeable batteries comes from China, which in turn gets 90 percent of its cobalt from Congo.

Without more public pressure and international guidelines and cooperation, we lack guarantees that resource-rich countries will meet decent environmental and governance standards. Not only will residents of these areas be at risk, the supplies for electric vehicles may be held hostage to unstable, corrupt regimes. We’ve been down that road before with oil, and we should avoid repeating it in the coming age of electric vehicles.