The Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach bring more goods into the U.S. than any other ports in the country. Yet together the ports are the single largest source of air pollution in Southern California.

The Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach bring more goods into the U.S. than any other ports in the country. Yet together the ports are the single largest source of air pollution in Southern California.

Harbor commissioners have adopted an ambitious plan to transition to cleaner fuels for goods movement in and around the ports in the next two decades. But achieving the vision for clean air will require answers to important questions:

- What are the prospects and potential for various zero-emission technologies – including battery electrification – to reduce pollution?

- How can finance, permitting and community engagement support the transition to cleaner fuels?

- What new policy and industry actions are needed for cost-effective deployment?

To address these questions, UCLA Law and UC Berkeley Law, with sponsorship from Bank of America, are hosting a free, daylong conference at UCLA Covel Commons on June 8, 2018. Panelists will examine the prospects and policy needs to move to a zero-emission future of goods movement in and around the ports. Speakers include the president of BYD Motors, CEO of ProTerra, CEO of Total Transportation Services, Inc. (TTSI) and CEO of the Coalition for Clean Air.

Also included will be representatives from:

- Bank of America

- California Trucking Association

- Earthjustice

- Port of Long Beach

- Southern California Edison

- Tesla Motors

- Union of Concerned Scientists

They will focus on steps that industry, government and civil society leaders must take to achieve zero-emission goods movement at the ports.

The event is free and open to the public, but advance registration is required, as space is limited. Please see the agenda and registration for more information.

Hope to see you there!

California can’t meet its long-term climate goals without reducing its overall driving miles, per a state analysis of greenhouse gas emissions through 2050. This point was echoed in a recent New York Times article on SB 827, the measure to lift local restrictions on transit-adjacent housing. In the Times piece, bill author State Senator Scott Wiener said:

We can have all the electric vehicles and solar panels in the world, but we won’t meet our climate goals without making it easier for people to live near where they work, and live near transit and drive less.

Wiener isn’t just making that claim up. According to the California Air Resources Board’s staff report on regional greenhouse gas emission reduction targets, the state will need a reduction in vehicle miles traveled (VMT) through 2035 and 2050, even with more zero-emission vehicles sold and renewable energy deployed. They have a simple chart showing the calculations:

Basically, if by 2035 half of all new cars sales are zero emission, with half of all electricity (and thus transportation fuels) coming from renewable sources, we will still need a 7.5% reduction in baseline VMT.

The good news is all that clean technology means there would be slightly less pressure to reduce driving miles. But as the staff report pointed out:

The GHG emissions reduction contribution from VMT is a comparatively smaller in share than the GHG emissions reductions called for by advances in technology and fuels, but necessary for GHG emissions reductions in other sectors such as upstream energy production facilities and natural and working lands, and are also anticipated to lead to important co-benefits such as improved public health.

My one critique of the analysis is that it is conservative on the renewable mix by 2035. California has a statutory requirement to achieve 50% renewables by 2030, and we’re already over 35%. I would guess we’ll be at 60% renewables by 2030 and maybe 65% by 2035, not including greenhouse-gas free hydropower. In addition, bullish estimates of zero-emission vehicles could have the state at 75% battery electric vehicle sales by 2035.

Still, the point remains that VMT reductions are crucial. And worse, these VMT efforts could be badly undermined by autonomous vehicles, which could encourage more driving as people take advantage of having robot chauffeurs for every little errand and trip.

All of this analysis points to the need for much more housing production near transit and jobs — an outcome that SB 827 would directly promote. Because clean technology alone won’t be sufficient when it comes to reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Tesla has been in the news recently for its falling stock prices and corporate troubles. The company’s stock has slid from a high that matched Ford Motor Company, even though Ford sold 64 times the number of vehicles as Tesla last year.

Tesla’s high valuation was based on its projected future market value. Unlike traditional auto companies, Tesla’s vision, if successful, would turn the company into your electric utility, gas station and auto dealer all rolled into one, through separate investments in solar and standalone batteries. Much of the hype was based on the profitability of its supposed first mass-market electric vehicle, the Model 3.

Demand is high for the vehicle, but the company can’t deliver. As Bill Saporito writes in the New York Times:

Tesla can’t seem to run an auto production line, something that the Detroit auto companies that Mr. Musk mocks are very good at. Ford’s electric vehicles and hybrids, such as the Fusion Energi, may not match the Tesla Model X in style or speed, but Ford can knock out millions of fenders and hoods in its stamping operations with absolute certainty and to tight specifications.

Tesla is operating out of the former G.M./Toyota joint venture plant in Fremont, Calif., which produced more than 400,000 cars annually at its peak. Tesla has been running at a quarter of that rate, and has had to resort to pulling cars off the line and finishing them by hand. That’s not what you call mass production; more like mass confusion.

The other problem is that the Model 3 isn’t really a mass-market vehicle. The company is only rolling out the higher-end version, which is priced at about $50,000 before incentives. Who knows if the cheaper version originally promised to consumers will be available at all this year?

Yet as Saporito points out, the global demand for — and investment in — electric vehicles is surging. The market overall is getting stronger, as battery prices fall precipitously.

Whether Tesla can participate in that coming boom will depend not only on its ability to mass produce Model 3s, but to ensure that they are of reliable quality. Otherwise, investor appetite in Tesla will start to wane, particularly as other automakers around the world catch up to the EV vision that Tesla helped pioneer.

KTVU Channel 2 news in the Bay Area covered EPA’s proposed rollback of Obama-era fuel economy standards last night, including an interview with me about the likely legal fight and economic repercussions:

Trump’s EPA just announced its intent to roll back fuel economy standards for all light-duty vehicles (passenger vehicles and trucks) between 2022 and 2025. The original standards were finalized in 2011 under the Obama Administration and in concert with California’s independent greenhouse gas standards for tailpipe emissions, with a goal of 54.5 miles per gallon vehicles by 2025. They would have saved 540 million metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions and 1.2 billion barrels of oil over the vehicles’ lifetime, according to government estimates.

EPA’s decision to loosen these standards will likely be challenged in court, notably by states that have adopted the stricter California standards. California adopted these standards pursuant to a waiver it received from the federal government under the federal Clean Air Act, which reserved for California the authority to develop air quality standards more stringent than federal ones. The waiver provision was included in the original act in recognition of the state’s unique air quality challenges and history as a pioneer in this area of regulation.

So what happens now? There are three potential outcomes:

- The state lawsuits are successful and the proposed rollback is delayed until a new administration takes over that is more interested in protecting the environment and public health over industry profit.

- The federal rollback is finalized and the country ends up with two markets for vehicles: a clean car market in California and the dozen states that have adopted the California standards, and a dirty car market in states that don’t have these higher standards. This outcome is not good for automakers, as they’d have to develop separate, cleaner cars for the California-led market. And it might be bad for consumers in these states who may lose access to some vehicles that would otherwise have been clean enough to sell in the California-led market.

- The federal rollback is finalized and the EPA tries to revoke California’s authority to set its own tailpipe standards. Never in history has an EPA administrator tried to revoke an existing waiver, but it seems likely that EPA chief Pruitt will try. My colleague Ann Carlson described the environmental and legal stakes with such a move. If the waiver is revoked, California will have a difficult time trying to achieve its near-term climate goals.

As with everything regulatory in nature, we’ll have to wait and see how the legal process plays out. But if EPA is successful in rolling back these standards, the agency will undermine the fight against climate change, increase toxic air pollution and attendant public health impacts, cost drivers money in terms of having to buy more gasoline for the same amount of driving, and diminish U.S. automaker competitiveness with international rivals who fully embrace more fuel-efficient and zero-emission vehicles.

Zero-emission vehicle technologies boil down to two options: battery electric and hydrogen fuel cells. Currently, battery electrics like Tesla’s vehicles and Chevy’s Bolt EV are dominating the field, as battery prices fall and range increases. Yet according as Bloomberg reports, auto industry executives are still apparently in love with hydrogen over batteries:

A KPMG survey last year found most senior automotive executives believe battery-powered cars will ultimately fail, with hydrogen offering the true breakthrough for electric mobility. That’s what Japan is banking on—Toyota Motor Corp. is making a big bet it will triumph over batteries.

Of the almost 1,000 officials polled by the Dutch advisory, some 78 percent said hydrogen cars will prevail because their tanks can be filled in minutes, making recharging times of 25-45 minutes for battery options “seem unreasonable.”

And yet this supposed advantage of faster charging time is eroding away, as super-fast chargers are being developed that could give an EV driver 200 miles of range in just a few minutes. And given that hydrogen stations are few and far between, what benefit is a faster charging time if it takes you 20 minutes to find a station?

What this survey tells me is that 78 percent of auto executives are not following battery technology very closely. Which I suppose presents opportunities for companies like Tesla to continue to do well in the market, if the rest of the industry doesn’t catch up soon.

I’m bullish on electric vehicles, for two big reasons:

- EVs offer a superior driving experience to gas-fueled cars

- EV costs are dropping rapidly, while the technology is greatly improving, with larger-capacity, more energy-dense batteries and faster charging times.

But oil industry leaders are apparently unafraid of this lurking threat. At a recent industry conference in Houston, Saudi Aramco CEO Amin Nasser told the crowd:

“I’m not losing any sleep over peak oil demand or stranded resources,” he said. “Oil and gas will continue to play a major role.”

Electric vehicles will not deliver rapid and economical reductions in carbon emissions until the electric fuel mix is sufficiently clean, Nasser said. He also sees coal remaining a big part of the energy mix for years to come, especially in places such as China and India.

“Right now, with electric vehicles, we are simply moving emissions from tailpipe to smokestack,” Nasser said.

Nasser is only partially correct. Around the world, and especially in the United States, we’re seeing significant improvements in deploying a cleaner electricity grid. With steep price decreases for solar PV and wind, this dynamic will continue to play out across the world, lowering emissions from EVs in the process. And in the meantime, driving an electric vehicle is only comparably dirty to a relatively high-mileage vehicle on a grid that is essentially entirely coal-powered, which will be much less common going forward.

But Nasser wasn’t done underestimating EVs:

As for vehicles, he said multiple technologies are in a race for the future, with options such as an advanced internal combustion engine, hybrids, plug-in vehicles, electric vehicles and hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles. Most vehicles on the road today have an internal combustion engine. There may be potential as well as challenges such as cost, durability and public acceptance, he said.

Technically, Nasser is correct that multiple low- and zero-emission vehicle options exist. But battery electrics are pulling away as the clear winner. Even companies like Toyota that have been pushing hydrogen fuel cell vehicles are now realizing that they need to catch up with battery electrics, at least on the passenger vehicle side. Costs, durability and public acceptance are all coming along, too, as automakers introduce new, more affordable long-range models.

Nasser wasn’t alone in his anti-EV sentiment at the conference:

Patrick Pouyanné, CEO of Total SA, told the CERAWeek gathering on Monday that he got an electric car to test. He called it silent and expensive, saying that renting a battery doesn’t save money compared with gasoline. He’s convinced big cities will see plenty of electric cars in 10 or 15 years because of air quality. But he still described a “longer story for oil in front of us,” noting uses such as airplanes and shipping.

It sounds like Pouyanné had an odd EV experience. For most EV drivers, it’s much cheaper than driving a gasoline-powered vehicle. And models like the Chevy Bolt and new Nissan LEAF have much longer range at affordable prices. Still, I agree with him that oil will still be needed in the medium-term for long-haul shipping and possibly aviation, if hydrogen and biofuels don’t catch up.

But there was one truly cautionary note for EV enthusiasts. Spencer Dale, a BP economist based at Rice University, modeled one “extreme” scenario where all new passenger vehicles had to be fully electric from 2040 onward (meaning a global ban on the internal combustion engine by that year). But even in that case, Dale calculated that global oil demand will still be higher 20 years from now than it is today, based on the increased number of vehicles on the road.

If anything, Dale’s modeling speaks to the need for more aggressive action on EVs around the world. From a climate perspective, we need to focus on transitioning our vehicles off of gasoline as soon as possible. While the oil industry may not see the urgency, those who care about the future of the planet sure do. But regardless of potential future policy actions, EVs are here to stay and grow, and it’s a threat that leaders in the oil industry appear to be underestimating.

Tesla has done amazing work pioneering electric vehicles and forcing positive change toward EVs within the broader industry. But the company will risk its progress and investor enthusiasm if it’s first “mass market” vehicle — the new Model 3 — is unreliable.

Tesla has done amazing work pioneering electric vehicles and forcing positive change toward EVs within the broader industry. But the company will risk its progress and investor enthusiasm if it’s first “mass market” vehicle — the new Model 3 — is unreliable.

And so far, the news is not good. Green Car Reports just reviewed the Model 3 and had this to report:

During the test itself, two things became clear: The Model 3 works largely as intended, and the build quality was the worst we have seen on any new car from any maker over the last 10 years.

The company was reviewing a car that had just been delivered in January, as production was ramped up at Tesla’s Fremont factory. The owner was not pleased with the vehicle:

We took delivery of our Model 3 today. It looked like everything was working OK until we got within about 10 miles of the house. That was when the touchscreen started to malfunction.

It is getting random touches along the right side of the screen. The worst part is that the stereo will go to full volume without notice. It also makes the map and navigation mostly useless. I called Tesla and they had me try rebooting the screen several times.

Unfortunately it didn’t resolve the issue. They said they would call me back [within 24 hours] to attempt a software update or to schedule a service call. Nothing like paying $50,000 to be a beta tester. Again.

I hope this is just a stroke of really bad luck for Tesla. But the higher-end Models S and X have also had these quality problems, although with an upper-income clientele that is more forgiving and able to weather having to bring their car to the shop. But the Model 3 is supposed to be an every day car for middle class buyers. So a reputation for unreliability could undermine that claim.

Tesla is relying on its brand as an innovative 21st century high-tech company with a luxury good. And certainly any new model car can have its growing pains, as we’ve seen for example with the otherwise high-quality Chevy Bolt EV. But if more stories about the cars falling apart surface, Tesla’s very survival could eventually be at stake.

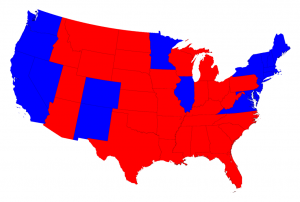

With Republicans in control of the federal government, climate advocates have looked to the states to make progress reducing greenhouse gas emissions. From my perspective, this is a positive and much-needed approach to climate action, given how relatively weak federal efforts on climate have been, even when Obama as president.

With Republicans in control of the federal government, climate advocates have looked to the states to make progress reducing greenhouse gas emissions. From my perspective, this is a positive and much-needed approach to climate action, given how relatively weak federal efforts on climate have been, even when Obama as president.

Progressive states can move much more aggressively and help pioneer policies and programs that can then become a model for the U.S. as a whole. And in the meantime, they can help bring down the costs of clean technologies like solar and electric vehicles, just through their market power. We’ve seen this play out in California.

But ClimateWire reported [pay-walled] that many of these state policy efforts are languishing, particularly the push to implement carbon pricing (through a carbon tax or cap-and-trade program):

Environmentalists have little hope of passing a proposed $35-per-ton carbon tax in New York, where Republicans control the state Senate. Connecticut and Rhode Island both have proposed enacting a $15-per-ton carbon tax, but only after Massachusetts acts. Massachusetts and Vermont both have Republican governors who acknowledge climate change, but are cool to the idea of a carbon tax.

Even in Oregon and Washington, states where the prospects for a carbon price may be best, climate hawks face long odds. Short legislative sessions and entrenched opposition to a cap-and-trade program in Oregon and carbon tax in Washington complicate the outlook for both proposals.

My question is: why are climate advocates focusing on carbon pricing in the first place? Nobody really likes tax increases, and the fight over what to do with the revenue seems to be dividing people. And in the bigger picture, a price on carbon may be less important at this stage of the climate fight than just getting these clean technologies to scale. After all, once renewable energy, zero emission vehicles, and other needed technologies are cheap, a carbon price should be much easier to implement, politically speaking.

I would prefer the focus at the state level be on setting strong greenhouse gas emission reduction targets through law, empowering key state agencies to achieve the targets (as happened in California), and boosting policies that help deploy clean technologies, such as electric vehicle incentives, aggressive renewable energy and energy storage mandates, and energy efficiency standards for new and existing buildings.

Once progress is made on these fronts, these states will have built up clean tech industries and the resulting political will needed to price the dirtier alternatives.

The federal tax bill back in December spared the generous $7500 EV tax credit that a purchaser of an electric vehicle now receives. But not all the automakers are jumping for joy about it, particularly GM and Tesla. As the New York Times explained:

That’s because as now structured, the tax credit puts Tesla and G.M. at a competitive disadvantage, especially compared with foreign rivals who are just starting to ramp up electric vehicle sales in the United States. The tax credit begins to phase out after a company sells 200,000 electric vehicles — a threshold both Tesla and G.M. are expected to reach this year.

Meanwhile, buyers of electric BMWs, Volkswagens and Volvos will continue to get the full $7,500 credit. All of those manufacturers have announced aggressive sales plans for electric vehicles in the United States but so far have sold relatively few of them.

It now seems clear that limiting the taxes to 200,000 vehicles per automaker, as opposed to an industry-wide credit or one that expires for all companies by a date certain, will penalize EV pioneers like Nissan, GM and Tesla going forward. Their vehicles will soon be more expensive than competitors’ who waited to introduce their EVs until now and will therefore have customers who can take advantage of the tax credit for their company.

It’s already affecting customers who want to buy Tesla’s “mass market” Model 3. Many of them were hoping to get the cheaper version of the vehicle before the tax credit expires for the company, but Tesla is first introducing the more expensive version of the car with longer range. Customers who want the cheaper model will probably be out of luck by then, tax credit-wise.

It’s already affecting customers who want to buy Tesla’s “mass market” Model 3. Many of them were hoping to get the cheaper version of the vehicle before the tax credit expires for the company, but Tesla is first introducing the more expensive version of the car with longer range. Customers who want the cheaper model will probably be out of luck by then, tax credit-wise.

With Republicans in charge of congress, it’s unlikely they’ll change the current EV tax credit structure. But ideally it would be reformed to affect all companies equally, while phasing out over time to reflect the decreasing costs of producing the vehicles.