EPA’s proposed rollback of federal clean car mileage standards would be crippling to U.S. efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. And its unprecedented proposed revocation of California’s ability to set stricter standards would specifically harm our state’s climate efforts.

EPA’s proposed rollback of federal clean car mileage standards would be crippling to U.S. efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. And its unprecedented proposed revocation of California’s ability to set stricter standards would specifically harm our state’s climate efforts.

I’ll be discussing the latest on this proposal this morning at 10am on KALW radio’s “Your Call” at 10am. I’ll be joined on the panel by Dr. Daniel Sperling, professor of civil engineering and environmental science and policy at UC Davis and member of the California Air Resources Board. It will be a follow-up to our recent KQED Forum appearance.

Tune in and call with questions!

The U.S. federal government has not provided much hope to climate advocates. The Trump administration has launched a full-scale assault on climate policies. But even under Obama, the level of action to tackle greenhouse gas emissions was not on pace with what’s needed to avert catastrophic warming.

But fortunately cities and states can do a lot on their own. America’s Pledge, an initiative co-founded by California Gov. Jerry Brown and former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, recently released a report that provides “bottom-up” strategies for cities, states, and businesses to address climate change. As Utility Dive summarized, the ten opportunity areas include the following:

- Expanding renewable energy

- Accelerating retirement of coal power

- Retrofitting buildings for energy efficiency

- Electrifying buildings’ energy use

- Accelerating the adoption of electric vehicles

- Phasing out the use of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs)

- Preventing methane leaks from gas wells

- Reducing methane leaks in cities

- Increasing carbon sequestration on land

- Establishing state and regional carbon markets

All of these areas do not necessarily require federal policy support (although it would be helpful), and many involve limiting emissions from powerful “short-lived climate pollutants” like methane and HFCs (I would also highlight land use and transit policies to promote smart growth as an important area of focus).

Straightforward examples at this level of policy making include developing energy efficiency building codes, steering municipal utilities to procure more renewable energy and energy storage, and providing incentives for electric vehicle adoption, such as through more charging stations and municipal fleet purchases.

But developing these policies at the state and local levels is more than just an effort to salvage climate policy in the face of federal inaction. We should be pursuing these policies anyway, for multiple reasons. Specifically, state and local action:

- Creates a decentralized web of climate policies that can’t be reversed with one bad national election that might deliver Congress or the presidency to climate deniers — producing more policy stability overall.

- Fosters local innovation that might result in successful programs or technologies that can scale nationwide or globally.

- Provides more accountability and flexibility on policy implementation, since decision makers will be in close proximity to those affected by the policies, both good and bad.

So while federal inaction on climate change can be a source of frustration and potential peril, it may also provide us with a good excuse to take action that needed to happen anyway — a silver lining on an otherwise dark storm cloud.

The electric vehicle revolution appears to be passing renters by. And the solution involves deploying more charging stations.

In a new working paper and blog by UC Berkeley energy economist Lucas Davis, he finds that homeowners are much more likely than renters to own an EV, even with similar incomes. He found, for example, that among households with incomes between $75,000 and $100,000 per year, 1 in 130 homeowners owned an EV, while only 1 in 370 renters owned one.

Why the discrepancy? As Davis explains, it’s about access to charging:

Most homeowners have a garage, a driveway or both. That makes charging extremely convenient for them because they can charge their vehicles at night.

It’s not so easy, however, for many renters. Renters are more likely to live in multi-unit buildings and parking spots may not be assigned, or there may not be any parking spots at all. The federal data doesn’t provide any information about parking availability, but this likely helps explain the disparity between homeowners and renter EV ownership rates.

There is also the related question of charging equipment. For homeowners, it is relatively straightforward to invest in a 240-volt outlet, electric panel upgrades and other improvements to speed up charging. These investments can cost $1,000 or more, but are a good investment for a homeowner planning to stay put.

Making this investment is trickier for renters, however. They may not want to invest their own money in a property they don’t own and their landlords may be unwilling to let them do it in any case due to liability and other concerns.

The best solution is to deploy more EV charging stations at workplaces and in fast-charging “plazas,” as we described in our 2017 Berkeley / UCLA Law report Plugging Away.

The best solution is to deploy more EV charging stations at workplaces and in fast-charging “plazas,” as we described in our 2017 Berkeley / UCLA Law report Plugging Away.

And more charging stations are needed not just for apartment dwellers and renters but to meet our climate goals more generally. In a recent report by the Center for American Progress, the authors found that most states in the U.S. have funded less than half of the deployment needed to meet our Paris climate accord commitment.

As E&E News reported on the study [paywalled]:

The analysis found that some 330,000 new public Level 2 and direct-current fast-charging stations would need to go up around the country by 2025.

At a cost of $4.7 billion, those networks would feed power to the 14 million plug-in hybrids and battery electrics necessary to bring greenhouse gas emissions from light-duty cars in line with the accord.

It’s a lot of money that’s needed — but also potentially a lot of revenue from selling electricity as vehicle fuel. With more utility and potentially automaker investment, this infrastructure goal should be feasible to achieve, if we muster the political will.

Some environmentalists have noted with schadenfreude that the auto industry is getting its just desserts now for pressing the Trump administration to weaken Obama-era fuel economy standards. While the auto industry may have originally just wanted some additional flexibility for compliance, instead they got a wholesale revocation of the program.

And this rollback means a worst-case scenario for the auto industry, with potentially years of litigation and uncertainty to come. In short, they won’t know what type of vehicles to produce for the next few years at least.

So if the auto industry didn’t want the administration to take this approach, why is it happening? The answer may involve the other industry that benefits from weakening fuel economy standards: Big Oil. As Bloomberg reported:

The Trump administration’s plan to relax fuel-economy and vehicle pollution standards could be a boon to U.S. oil producers who’ve quietly lobbied for the measure.

The proposal, released Thursday, would translate into an additional 500,000 barrels of U.S. oil demand per day by the early 2030s, about 2 to 3 percent of projected consumption, according to government calculations.

Apparently oil industry leaders have been quietly lobbying for this action, including Marathon Petroleum Co., Koch Companies Public Sector LLC, and the refiner Andeavor. In fact, on the KQED Forum show I participated on this past Friday, one of the guests supporting the rollback was from the Koch-funded think tank “Pacific Research Institute.”

So it looks like Big Oil doesn’t really care if the auto industry twists in the wind on the rollback, if it means the possibility of selling a lot more climate-destroying oil in the meantime.

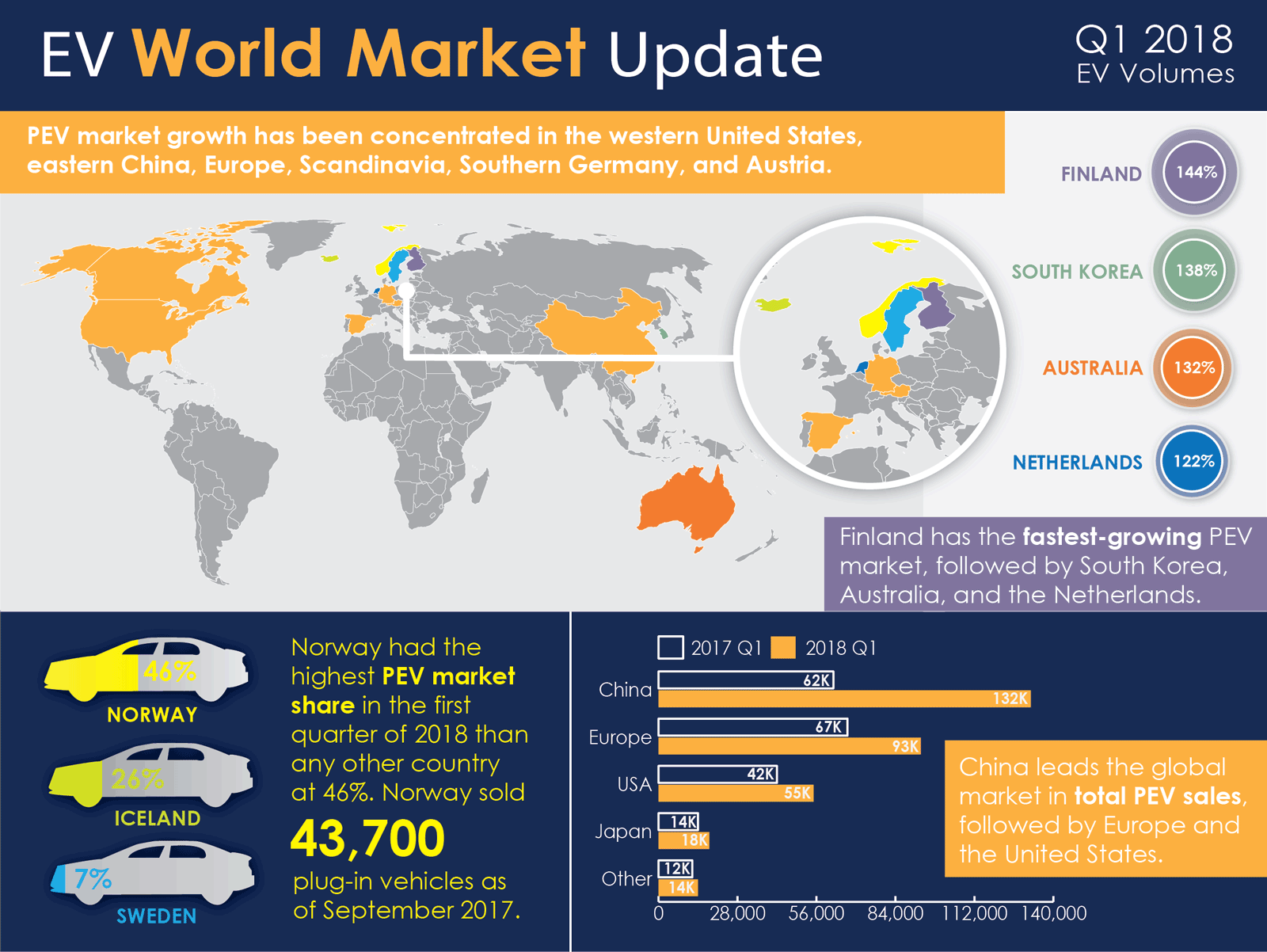

As the Trump administration retreats on zero-emission vehicle leadership, it’s worth remembering that electric vehicles are part of a global market. In a recent blog post, Tom Turrentine and Kathryn Canepa at UC Davis made it easy to visualize the world map of where EVs are selling:

Overall, there is a lot of good news about the sales trajectories both globally and within individual countries:

In 2017, the global PEV market [including battery and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (EVs)] grew by 65%, hitting 1.2 million PEV sales. During the first half of 2018, sales grew at an even faster pace.

….

Fastest growth? That would be Finland, with 144% market growth from last year. South Korea (+138%), Australia (+132%), Netherlands (+122%), Spain (+118%), and Canada (+114%) are following closely. China’s already-established market grew 113% from 2017.

Turrentine and his UC Davis colleagues separately lay out the top five policy recommendations for jurisdictions to boost electric vehicle sales in a new report [PDF]. They include:

- Vehicle purchase incentives

- Reoccurring incentives for driving electrically

- Robust charging networks

- Widespread consumer understanding of and experience with zero-emission vehicles

- Regulations on automakers to encourage EV production

Within the United States, California is certainly following this playbook. And as we can see from the map above, a number of other jurisdictions — notably China and Europe — are also following suit.

Which is why the U.S. as a whole now risks getting left in the dust by this growing global industry.

Battery electric buses are already cost-competitive with fossil-fueled buses, based on their lower fuel and maintenance costs. Transit agencies around the country are starting to purchase them in bulk from companies like BYD and ProTerra.

But is electricity really cleaner than a natural gas-fueled bus? Union of Concerned Scientists tackled this question in California previously and found positive results, per UCS’s Jimmy O’Dea, and now they’ve taken their research nationwide:

We answered this for buses charged on California’s grid and found that battery electric buses had 70 percent lower global warming emissions than a diesel or natural gas bus (it’s gotten even better since that analysis). So what about the rest of the country?

You many have seen my colleagues’ work answering this question for cars. We performed a similar life cycle analysis for buses and found that battery electric buses have lower global warming emissions than diesel and natural gas buses everywhere in the country.

Here’s the UCS map:

Meanwhile, the buses are getting cheaper and better, as ProTerra’s CEO Ryan Popple explained recently to E&E News [paywalled]:

Meanwhile, the buses are getting cheaper and better, as ProTerra’s CEO Ryan Popple explained recently to E&E News [paywalled]:

When we started out, we could really only do circulator-style routes, and we needed a fast charger for every route. That was probably five years ago, and that was because our maximum theoretical range was probably 50 miles. Now we’re regularly seeing our electric buses do anywhere between 175 and 225 miles in real service. And with all sorts of topography.

But despite the technological advancements and environmental benefits, supportive policy is still needed. Here’s the top of Popple’s policy wish list:

It is at the state of California, and it is the Innovative Clean Transit rule, the ICT. That is headed to the California Air Resources Board for an initial vote, I think, in September, and it could be fully implemented by the end of this year. What that ruling will do is set a long-term target for every transit vehicle in the state of California and a date certain by which it must eliminate its tailpipe emissions, so basically it has to become a zero-emissions vehicle… The reason it matters to us is just so that the industry can move forward with long-term planning on electric fleets.

And as more transit agencies move forward with zero-emission vehicles, we now have assurance that the clean air benefits are real — all across the country.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, under new management with the recent sacking of Scott Pruitt, will apparently be moving ahead next week with a proposed rollback of national fuel economy standards post 2020. The agency will also try for the first time in history to revoke a previously granted waiver to California to allow the state to set more aggressive standards and require automakers to produce a certain number of zero-emission vehicles, per E&E [pay-wall]:

EPA is expected to propose a rule in the coming days to prevent the standards from rising past the 2020 levels established under former President Obama, who hailed those increases as a major step toward addressing rising temperatures.

Also in the crosshairs is a California waiver under the Clean Air Act that allows it and more than a dozen other states to surpass federal car rules. EPA is expected to ask for comment on rescinding the waiver, a move that many see as a signal of the administration’s intent to do just that.

The move will set off a battle royale of litigation, probably taking years to resolve and possibly relying on the swing vote of whomever fills Justice Kennedy’s seat on the U.S. Supreme Court.

The move will set off a battle royale of litigation, probably taking years to resolve and possibly relying on the swing vote of whomever fills Justice Kennedy’s seat on the U.S. Supreme Court.

If the agency is successful (and if Trump is re-elected in 2020), it will probably badly damage the electric car market in the U.S., particularly in California, where the ZEV mandate has been the critical policy tool for encouraging automakers to introduce new EV models.

All of this retrograde action sets the stage for China to eat our lunch:

China’s generous subsidies to electric vehicle makers have created a massive field of producers, and it’s only growing.

The industry is one of 10 identified for state investments three years ago as part of President Xi Jinping’s Made in China 2025 plan. A total of 487 companies currently exist, fueled by $15 billion in direct subsidies for EV sales over the last five years.

Those subsidies are still coming: In June, the National Development and Reform Commission and China Construction Bank Corp. announced an additional $47 billion fund for high-tech industries, including EVs.

While I’m happy to see international investment in EVs continue, it’s depressing to see the Trump Administration try to roll back progress on this environmentally crucial — and economically beneficial — clean transportation technology.

California has already achieved a landmark climate goal, we learned yesterday. Newly released data from 2016 by the California Air Resources Board show that the state’s greenhouse gas emissions decreased 2.7 percent to 429.4 million metric tons.

That number is significant because it’s below the 431 million metric tons the state produced in 1990, which is the level California law requires we achieve once again by 2020. And we’re now four years early on achieving that goal. Since our peak emissions in 2004, California has since dropped those emissions 13 percent.

Much of the reduction is due to significant increases in renewable energy production. Going forward, the next challenge will be a further 40 percent reduction below these 1990 levels by 2030, per SB 32 (Pavley, 2016). And that will require major decreases in emissions from the transportation sector — primarily through greater adoption of zero-emission vehicles.

Importantly, these emission reductions have occurred during a booming economy. The state has effectively de-linked economic growth from carbon-based energy. And all of this economic growth defies industry predictions back in 2006 when the 2020 goal in AB 32 was originally legislated.

As the Sacramento Bee reported at the time during the legislative debates:

[T]he measure [AB 32] is vigorously opposed by the California Chamber of Commerce and the petroleum industry.

”Climate change is real, and we do need to do things,” said Victor Weisser, president of California Council for Environmental and Economic Balance, which represents oil firms. ”But greenhouse gas emissions reduction in California is going to be very expensive.”

In short, industry was not pleased with the climate goals and believed they would cause economic calamity, as another Bee article related:

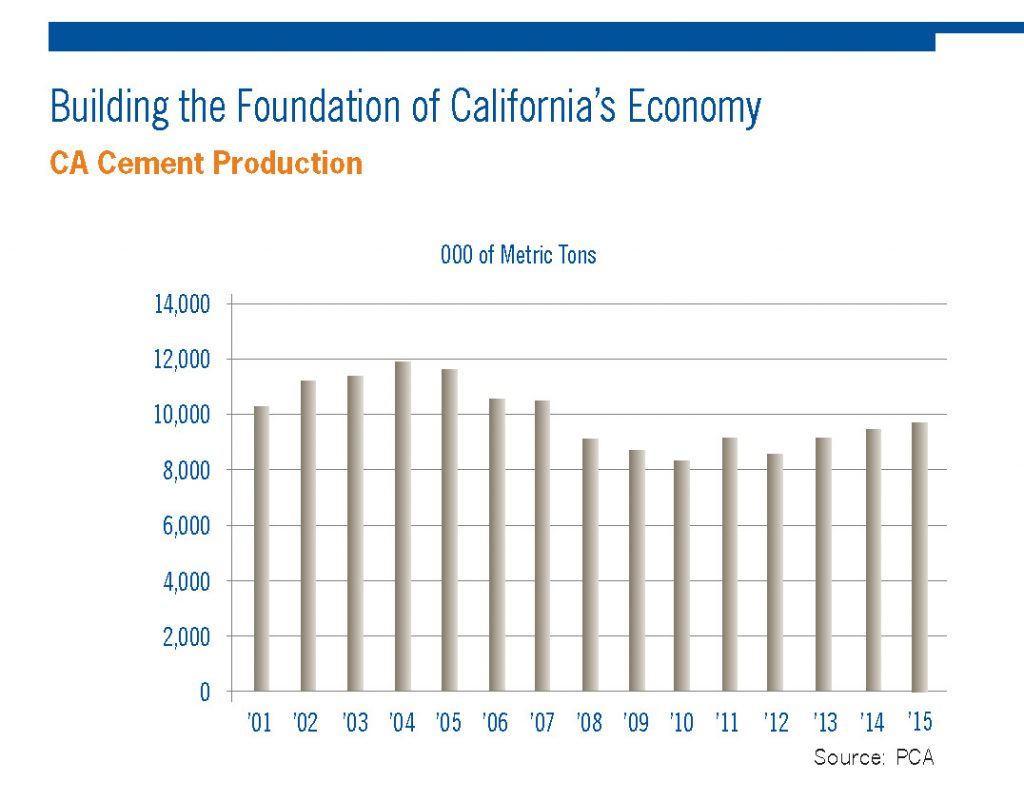

“We don’t think heavy-handed regulation and bureaucracy is necessary,” said Thomas Tietz, who heads the California Nevada Cement Promotion Council.

Backers say AB 32 would spur new technologies, but Tietz warned that such caps will backfire on the local economy. He said the bill would drive cement producers out of state and force California to import materials produced from countries or states with less stringent environmental rules.

In retrospect, these predictions have not come true. Cement production hasn’t left the state, as industry figures show (although the sector hasn’t fully recovered since the last recession):

Overall, California’s success is a powerful example for the rest of the world and some important good news in the global fight against climate change.

Overall, California’s success is a powerful example for the rest of the world and some important good news in the global fight against climate change.

With much of the credit due to the proliferation of inexpensive renewable energy, the next challenge will be to ensure similar progress with zero-emission vehicle technology. And given the state’s track record on climate so far, we should be hopeful that similar success is achievable for 2030.

Due to work- and vacation-related travel most of this month, I plan to take June off from blogging.

In the meantime, some stories worth following on some of the issues I’ve been covering on this blog:

- Solar PV: Are the Trump solar tariffs actually bringing more solar manufacturing to the U.S.? Or does automation mean it’s just a different location for foreign-owned factories, as I originally suspected? Bloomberg reports.

- Electric vehicles:Tesla addressed Consumer Reports’ concern about braking distance on the new Model 3 with a pretty amazing over-the-air software update. Ars Technica thinks that’s good but also a bit troubling about the quality of the car’s braking system.

- Housing bills in California: SB 828 (Wiener) and AB 2923 (Chiu), two bills I’ve blogged about that will boost housing near transit, both passed their houses of origin. The Real Deal covers SB 828, and Greenbelt Alliance supports AB 2923.

See you in July!

It’s fine if you don’t like Elon Musk. But it’s a mistake to let antipathy for Musk’s ideas, businesses and public persona color your view of electric vehicles, and more specifically Tesla.

And that’s exactly what happens to token “conservative” New York Times opinion writer Bret Stephens. Stephens is otherwise known (at least to me) as a climate skeptic. But in a scathing and highly personal attack on Elon Musk, he betrays ignorance of another subject: electric vehicles.

After comparing Musk to Trump, he makes some misleading charges about Tesla:

Strong words — too strong, if you ask the satisfied customers of Tesla’s Model S (base price, $74,500) and X ($79,500). But Tesla is supposed to be the auto manufacturer of the future, not a bauble maker for the rich.

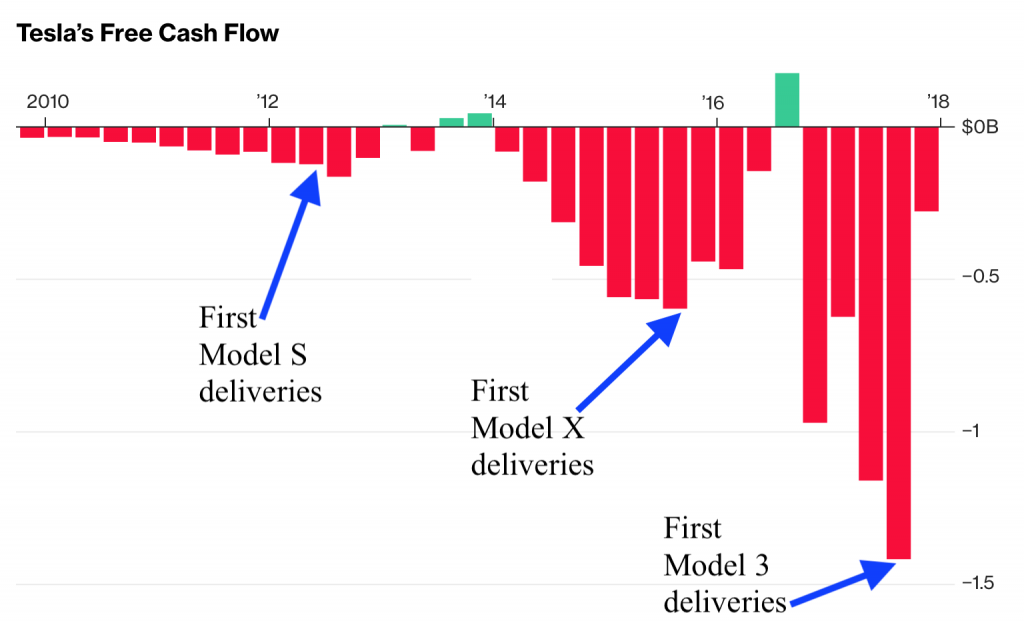

The company has rarely turned a profit in its nearly 15-year existence. Senior executives are fleeing like it’s an exploding Pinto, and the company is in an ugly fight with the National Transportation Safety Board. It burns through cash at a rate of $7,430 a minute, according to Bloomberg. It has failed to meet production targets for its $35,000 Model 3, for which more than 400,000 people have already put down $1,000 deposits, and on which the company’s fortunes largely rest.

Stephens makes Tesla sound like a money-losing luxury automaker. But Tesla could have easily turned a profit a long time ago, if it was in the short-term profit game. But it’s burning cash precisely because it’s scaling up a massive battery, solar panel and mass-market vehicle business. Check out this chart on Tesla cash flow from Ars Technica:

It’s silly for Stephens to take a snapshot of Tesla’s current losses without broader context and insight into the company’s business plan. He whiffs on this score.

It’s silly for Stephens to take a snapshot of Tesla’s current losses without broader context and insight into the company’s business plan. He whiffs on this score.

But it gets worse. He then lobs a broad attack against EVs in general:

Tesla, by contrast, today is a terrible idea with a brilliant leader. The terrible idea is that electric cars are the wave of the future, at least for the mass market. Gasoline has advantages in energy density, cost, infrastructure and transportability that electricity doesn’t and won’t for decades. The brilliance is Musk’s Trump-like ability to get people to believe in him and his preposterous promises. Tesla without Musk would be Oz without the Wizard.

Much of the blame for the Tesla fiasco goes to government, which, in the name of green virtue, decided to subsidize the hobbies of millionaires to the tune of a $7,500 federal tax credit per car sold, along with additional state-based rebates. Would Tesla be a viable company without the subsidies? Doubtful. When Hong Kong got rid of subsidies last year, Tesla sales fell from 2,939 — to zero. It may be unfair to describe Tesla as Solyndra on wheels, but only slightly.

It’s time for fact checks. First, lithium ion batteries and electricity rival gasoline in all categories Stephens mentions. Electricity is ubiquitous (and locally produced). Batteries can recharge in minutes with technology now being introduced on the market, just like a gas station. And cheaper battery packs deliver the range today of a full tank of gas. And on all these fronts, the technology and infrastructure is set to improve in the next few years — not decades, as Stephens suggests.

But even more important, electricity as a fuel doesn’t poison our air and lungs like burning gasoline — or leave us dependent on foreign governments for a global commodity. Gasoline is not priced for those externalities. Since Stephens doesn’t accept climate science, he may not care. But the rest of us should.

And this notion that Tesla survives on government handouts is also misleading. Many Tesla customers are wealthy enough where the tax incentives and rebates don’t factor into their decision-making, according to data collected in California on rebate customers. If anything, Tesla is now hurt by government incentives for fossil fuels and rival automakers with new electric vehicles on the market.

In short, Stephens is ignorant on this topic and unfortunately has written a column that spreads misinformation on a critical climate-fighting technology.