Scientists have been stunned by a recent surge in climate warming, potentially exacerbated by warm waters during the recent El Nino event, per E&E News [paywalled]:

Global temperatures rose by a record-breaking amount between 2014 and 2016, new research finds.

Over the course of three years, mean surface temperatures jumped by nearly a quarter of a degree Celsius, or more than 0.4 degree Fahrenheit. That’s a whopping 25 percent increase over the total amount of warming the Earth has experienced in the last 150 years. The research is published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

“As a climate scientist, it was just remarkable to think that the atmosphere of the planet could warm that much that fast,” Jonathan Overpeck of the University of Arizona, one of the paper’s authors, said in a statement.

Basically, it appears that most of the warming on Earth over the past few decades has been absorbed by the oceans, which then released a lot of that heat during the recent El Nino event.

This kind of data isn’t exactly news to those who have seen the changes on the ground, particularly in our western mountains. Take for example the reclusive 67-year-old Billy Barr, who has spent the last 46 years in a remote cabin in the Rocky Mountain woods. In a Denver Post profile, Barr describes how he began taking notes every day on weather in 1974 out of boredom, recording the low and high temperatures, snow-water equivalent and snowpack depth.

He doesn’t necessarily analyze his data. But he’s seeing a trend: It’s getting warmer. The snow arrives later and leaves earlier.

Lately, he’s charting winters with about 11 fewer days with snow on the ground; roughly 5 percent of the winter without snow. In 44 years, he’d counted one December where the average low was above freezing — until December 2017, when the average low was 35 degrees.

Interview with billy barr, accidental captain among climate researchers

Denver PostMore than 50 percent of the record daily highs he’s logged have come since 2010. In December and January this season, he already has counted 11 record daily-high temperatures. Last year he tallied 36 record-high temperatures, the most for one season. Back in the day, he would see about four, maybe five record highs each winter.

Meanwhile, Colorado just had its second-warmest year on record and is now at a 30-year low in snowpack. And in California, a study published in the hydrological science journal Water shows that in Tahoe and the northern Sierra Nevada mountains, the average elevation of the “snow line,” where snow turns to rain during a storm, has risen roughly 236 feet over the last 10 years.

All in all, the global data show more of these on-the-ground changes in our near future.

This has been a tough year for the environment at the national level in the U.S. We’ve seen rollbacks of key protections, gutting of enforcement, efforts to open up resource extraction on public lands, and a general abdication of climate leadership at home and globally.

On the bright side, states and cities have stepped into the void, providing some good news. And nonprofits have had wins at the courts and at various other levels of government. Businesses, meanwhile, have also made progress, particularly on various clean technologies like battery electric vehicles and renewables. Business leaders have also become strong advocates for climate action globally.

And internationally, countries like China are now aggressively tackling carbon emissions, both with carbon markets and other efforts to control pollution, as well as by promoting clean technologies.

With the holidays here, I’ll be off blogging until the new year, which will hopefully bring some better results overall than we’ve seen in 2017 on the environment and other critical challenges facing the globe.

Wishing everyone the best until then. And in the meantime, enjoy Joni Mitchell’s reflective take on the holidays from 1971:

Climate change and the recent five-year drought in California have now rendered 129 million trees dead in the Sierra Nevada mountains. As a result, they are more susceptible to catastrophic wildfires like we’ve seen this fall in the state’s coastal areas. California’s Sierra Nevada Conservancy has an informative webpage and videos dedicated to educating the public about the urgent need to manage the forests better.

The first video describes the immediate need for action, particularly given the forests’ role as a carbon sink, which could turn to carbon emitter without better management:

The next video shows the risk of continued fire suppression and need for more controlled burns:

The final video shows what controlled burns can do to restore the forest ecosystem and provide carbon benefits:

But as UC Berkeley forest expert Van Butsic described in a recent interview with Water Deeply, the solutions will be controversial, most likely requiring “mechanical thinning” in forests that some environmental groups oppose. Yet as the videos above make clear, the price of continued inaction and fire suppression will only exacerbate the environmental catastrophe we are facing in these beautiful mountains.

When President Trump announced in June that the United States would be withdrawing from the Paris climate agreement, France eagerly stepped into the leadership void. French President Macron responded by offering millions in new grant money for climate science research.

The winners were just announced, including 13 American scientists out of the 18 winners. I spoke to KCBS radio in San Francisco yesterday about the program and what it means for the United States going forward. You can listen to the 4 minute clip here:

Sean Illing in Vox.com conducted a fascinating interview with Steven Sloman, a professor of cognitive science at Brown University, about how we arrive at the conclusions we do. In short, the process (and outcomes) are not pretty, as Dr. Sloman relates:

Sean Illing in Vox.com conducted a fascinating interview with Steven Sloman, a professor of cognitive science at Brown University, about how we arrive at the conclusions we do. In short, the process (and outcomes) are not pretty, as Dr. Sloman relates:

I really do believe that our attitudes are shaped much more by our social groups than they are by facts on the ground. We are not great reasoners. Most people don’t like to think at all, or like to think as little as possible. And by most, I mean roughly 70 percent of the population. Even the rest seem to devote a lot of their resources to justifying beliefs that they want to hold, as opposed to forming credible beliefs based only on fact.

Think about if you were to utter a fact that contradicted the opinions of the majority of those in your social group. You pay a price for that. If I said I voted for Trump, most of my academic colleagues would think I’m crazy. They wouldn’t want to talk to me. That’s how social pressure influences our epistemological commitments, and it often does it in imperceptible ways.

He concludes that if the people around us are wrong about something, there’s a good chance we will be too. Proximity to truth compounds in the same way. And the phenomenon isn’t a partisan problem; it’s a human problem on all sides of political debates.

In some ways, it’s understandable how this dynamic arose in our species. There’s no way one brain can master all topics, so we have to depend on other people to do some thinking for us. This is a perfectly rational response to our condition. It also may explain why traditional societies often relied on a few religious leaders to make a lot of the key decisions for a society that would rather not have to think too hard about broader societal problems and instead focus on problem-solving in their own immediate lives. The problem though becomes when our beliefs support ideas or policies that are totally unjustified.

So are we doomed to a fate of group-think with the risk of unsupportable beliefs? Dr. Sloman doesn’t think so, noting that some professions train people not to fall into this trap:

People who are more reflective are less susceptible to the illusion. There are some simple questions you can use to measure reflectivity. They tend to have this form: How many animals of each kind did Moses load onto the ark? Most people say two, but more reflective people say zero. (It was Noah, not Moses who built the ark.)

The trick is to not only come to a conclusion, but to verify that conclusion. There are many communities that encourage verification (e.g., scientific, forensic, medical, judicial communities). You just need one person to say, “are you sure?” and for everyone else to care about the justification. There’s no reason that every community could not adopt these kinds of norms. The problem of course is that there’s a strong compulsion to make people feel good by telling them what they want to hear, and for everyone to agree. That’s largely what gives us a sense of identity. There’s a strong tension here.

He’s also pioneering some research on ways to reframe political-type conversations from a focus on what people value to one about actual consequences. As he notes, “when you talk about actual consequences, you’re forced into the weeds of what’s actually happening, which is a diversion from our normal focus on our feelings and what’s going on in our heads.”

This work could contribute to a better understanding about public perceptions around climate change. For example, the denial of basic climate science can certainly be attributed to group-think. But as Sloman posits, reframing the messaging from the science to the outcomes of climate mitigation (such as a cleaner world, less dependence on extractive industries for fuel) might open more in the middle to taking action. We could also focus on training the next generation to be more open-minded on evidence and arguments, as with the scientific, medical and judicial fields.

But just being aware of our mental processing of information and beliefs is a good start to addressing the problem of when those processes take us in the wrong direction.

California’s 2030 climate goals will be a big step forward for the state. We’re already making good progress achieving our 2020 goals (to return to 1990 levels of carbon emissions), with the state likely to hit that goal a bit early thanks to the global recession and the plummeting price of renewables. But the 2030 goals require an additional 5% reduction per year in emissions for the 2020s, to reduce our levels 40% below 1990 emissions. That’s a tall order.

Electric utilities will be a big part of the solution, but not just because of their efforts to decarbonize the electricity supply. They’re also needed to expand the kinds of things that can run on electricity instead of petroleum or natural gas.

Southern California Edison makes that case and puts numbers behind it, in a recent white paper the utility commissioned, per E&E news:

SCE used an analysis from the consulting firm E3 that found the cheapest of three pathways to meeting the state’s 2030 emissions goals entails electrifying 24 percent of light-duty vehicles and 15 percent of medium-duty vehicles, in addition to reaching an 80 percent carbon-free electricity target. It also would require 30 percent of residential and commercial water and space heaters to run on electricity rather than gas.

This pathway seems achievable at a reasonable cost, given the advances in battery technologies on the vehicle side. Still, we will need to keep the federal tax credit in place or find a viable substitute to keep demand for EVs strong in the short run.

On the furnace and water heating side, we’ll need some new, cheaper products to wean buildings off of natural gas and onto clean electricity. But the good news is that achieving the 80% carbon-free electricity goal by 2030 may not be so daunting, given that we may be on track for 60% renewables by 2030 anyway, plus all the large hydropower that doesn’t count under the renewables mandate.

As always with the future, there are plenty of variables and unknowns. But California’s progress to date on clean tech gives us a clear idea of what’s needed — and what the costs may be — to achieve the 2030 goals.

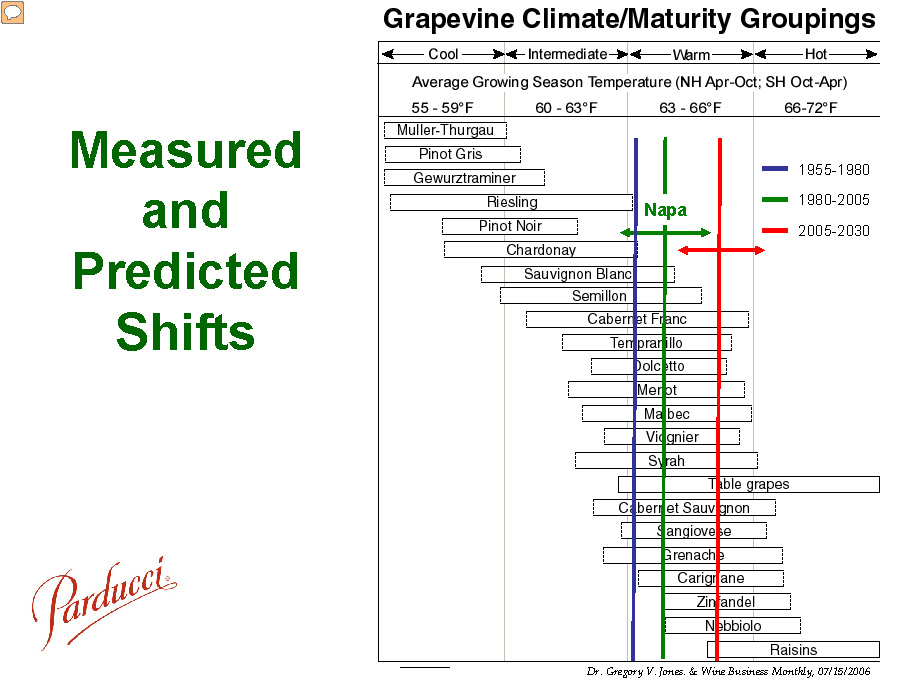

Back in 2009, when I first started working full time on climate change law and policy at Berkeley Law, I saw a presentation by a representative of a Napa winery at a California Assembly select committee hearing on climate change. Thomas A. Thornhill III, a partner at Parducci Wine Cellars/Paul Dolan Vineyards, showed the following slide:

As you can see from the chart, as the temperature warms (the red line), certain Napa grapes just won’t be able to survive anymore in the Valley, such as chardonay and sauvignon blanc (although it’s good news for raisin production in the Valley, for what that’s worth)

As you can see from the chart, as the temperature warms (the red line), certain Napa grapes just won’t be able to survive anymore in the Valley, such as chardonay and sauvignon blanc (although it’s good news for raisin production in the Valley, for what that’s worth)

I thought about that slide over Labor Day weekend this year, when a record-breaking heat wave with temperatures up to 117 degrees hit Napa. This new normal of extreme weather destroyed some of Napa and Sonoma’s premium cabernet grapes, as Bloomberg reported:

Vineyard consultant Steve Matthiasson, who also makes wines under his eponymous label, admitted, “The heat wave screwed us up.” While you need warmth to ripen cabernet, you don’t want too much, and this summer Napa had more than two dozen days with temperatures over 100 degrees. Before the grapes were completely ripe, an extreme heat wave on Labor Day weekend, which didn’t cool down at night, caused grape dehydration. As juice evaporated, some of the unripe grapes shriveled into raisins.

As a result, the wine grape crop is likely to be smaller than expected this year in California and beyond, down from 5 to 35 percent for some individual blocks of vines.

While this was a high-end casualty of climate change, it’s a demonstration of what will happen to the broader multi-billion agricultural industry across places like California as we veer into an increasingly hotter world.

And that’s nothing to toast.

America’s Christian conservatives are pretty well known at this point for being anti-climate science and environmental action. As Bernard Daley Zaleha and Andrew Szasz write in Why Conservative Christians Don’t Believe in Climate Change, studies show that:

America’s Christian conservatives are pretty well known at this point for being anti-climate science and environmental action. As Bernard Daley Zaleha and Andrew Szasz write in Why Conservative Christians Don’t Believe in Climate Change, studies show that:

[T]he higher the level of religious commitment (as measured by self-reports of religion’s personal importance, frequency of religious service attendance, and frequency of prayer), the lower the level of environmental concern. Another recent study showed, similarly, that American Christians, collectively, when considered without regard for denomination, have less environmental concern than do Americans of other faiths or those who say they are not affiliated with any institutional forms of religion.

Now I’m far from a religious expert, but it seems to me that the Bible — specifically the story of Noah — features a Judeo-Christian God with a history of using extreme weather (i.e. climate change) to further his purposes. Check out this translation of the story of Noah:

The Lord saw how great the wickedness of the human race had become on the earth, and that every inclination of the thoughts of the human heart was only evil all the time. The Lord regretted that he had made human beings on the earth, and his heart was deeply troubled. So the Lord said, “I will wipe from the face of the earth the human race I have created—and with them the animals, the birds and the creatures that move along the ground—for I regret that I have made them.” But Noah found favor in the eyes of the Lord

…

Now the earth was corrupt in God’s sight and was full of violence. God saw how corrupt the earth had become, for all the people on earth had corrupted their ways. So God said to Noah, “I am going to put an end to all people, for the earth is filled with violence because of them. I am surely going to destroy both them and the earth.

It’s easy to see the parallel with this story to today’s struggle with climate change. The climate crisis is caused by emissions of greenhouse gases from burning carbon fuels to power our economy. While a strong economy is a necessity and can be force for moral goodness, it’s also based on greed in a way that the God of the Bible might easily condemn as “wickedness.” Pope Francis has certainly drawn similar conclusions.

It’s easy to see the parallel with this story to today’s struggle with climate change. The climate crisis is caused by emissions of greenhouse gases from burning carbon fuels to power our economy. While a strong economy is a necessity and can be force for moral goodness, it’s also based on greed in a way that the God of the Bible might easily condemn as “wickedness.” Pope Francis has certainly drawn similar conclusions.

At the very least, continuing on this current path without heed for the consequences certainly sounds stupid, in a “times of Noah” kind of way. So wouldn’t this story be an eye-opener (or at least a conversation-starter) for Christian conservatives to think about climate science?

Jesse Jackson took this approach in a recent column imploring for more climate preparedness:

In Genesis, the Bible teaches that God came to Noah and warned him about the coming floods. He told Noah to build an ark — sophisticated infrastructure — to ensure that man and selected animals and birds could survive. There was no nonsense about each being on his or her own. Strong swimmers went down with the weak. Rich mansions on the hill were flooded with the poor huts in the valley. It took infrastructure, planning and preparedness to survive the flood.

I know there are researchers and advocates trying to reach this community and get them involved with climate solutions. But given the plain text of their religious document, I’m surprised it’s such an uphill battle.

The unfolding tragedy in Houston from catastrophic rainfall and resulting flooding is probably worsened by two human-caused factors: climate change and bad land use planning. On the climate science, Michael Mann explains how warming waters in the Gulf of Mexico leads to greater rainfall:

The unfolding tragedy in Houston from catastrophic rainfall and resulting flooding is probably worsened by two human-caused factors: climate change and bad land use planning. On the climate science, Michael Mann explains how warming waters in the Gulf of Mexico leads to greater rainfall:

There is a simple thermodynamic relationship known as the Clausius-Clapeyron equation that tells us there is a roughly 3% increase in average atmospheric moisture content for each 0.5C of warming. Sea surface temperatures in the area where Harvey intensified were 0.5-1C warmer than current-day average temperatures, which translates to 1-1.5C warmer than “average” temperatures a few decades ago. That means 3-5% more moisture in the atmosphere.

That large amount of moisture creates the potential for much greater rainfalls and greater flooding. The combination of coastal flooding and heavy rainfall is responsible for the devastating flooding that Houston is experiencing.

But at the same time, the city is woefully unprepared for what appears to be a sadly predictable storm. Neena Satija previewed these events in a story last year in the Texas Tribune, in which she blamed poor local land use decisions for the city’s lack of resilience to this type of storm:

Scientists, other experts and federal officials say Houston’s explosive growth is largely to blame. As millions have flocked to the metropolitan area in recent decades, local officials have largely snubbed stricter building regulations, allowing developers to pave over crucial acres of prairie land that once absorbed huge amounts of rainwater. That has led to an excess of floodwater during storms that chokes the city’s vast bayou network, drainage systems and two huge federally owned reservoirs, endangering many nearby homes — including Virginia Hammond’s.

As my colleague Dan Farber notes on Legal Planet, this storm would have caused bad flooding no matter what. But locals throughout the country need to prepare for the “new normal” of climate change with storms and other events like these.

The resiliency planning will cost money and also mean other types of sacrifice. For example, in Houston’s case, large swaths of prairie should probably have been preserved rather than be developed. In other words, infill and smart growth development can be a crucial climate resiliency strategy. As a model here in California, I think of the Yolo Bypass by Sacramento and how that set aside of land for overflow from the Sacramento River saved the city from catastrophic flooding this year.

The events in Houston will hopefully be a wake-up call around the country that we need to preserve and bolster more natural systems to deal with the coming onslaught of extreme weather events, as well as build in smarter locations. And we’ll need forward-thinking people with the will to fund and implement these solutions.

The people who deny climate science the most aren’t stupid, but actually are among the smartest, a new study confirms. Previous studies I’ve blogged about have documented this phenomenon, and now a new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences documents the trend on a range of scientific — yet politicized — issues.

The people who deny climate science the most aren’t stupid, but actually are among the smartest, a new study confirms. Previous studies I’ve blogged about have documented this phenomenon, and now a new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences documents the trend on a range of scientific — yet politicized — issues.

As E&E news summarizes [pay-walled]:

Looking at a nationally representative survey of views on stem cell research, the Big Bang, human evolution, nanotechnology, genetically modified organisms and climate change, researchers at Carnegie Mellon University found that respondents with the most education and the highest scores on scientific literacy tests had the most polarized beliefs.

On climate change, the researchers found that political identity was a more important signal of where respondents stood than their academic acumen or scientific sophistication.

“Conservatives with higher scores display less concern about climate change, while liberals with higher scores display more concern,” the authors wrote. “These patterns suggest that scientific knowledge may facilitate defending positions motivated by nonscientific concerns.”

The take-home point for advocates of climate action is that more facts won’t change people’s minds. It’s not a question of ignorance that motivates this reasoning. Instead, advocates should focus on new frames to address the challenge, as well as on specific facets of climate change that don’t require someone to accept all the science around it, like reducing air pollution or addressing sea level rise.

Essentially, climate change has become an issue of tribal identity and ideology — and no longer one of fact and reason. While that’s disheartening, it’s also clarifying for understanding how to move forward on the issue.