It’s always dangerous to generalize, but in the case of neighborhood opposition to new development, I can’t resist. In California, this neighborhood opposition is the prime reason why the state has under-produced housing since the 1970s, leading to economic inequality and environmental degradation — not to mention under-performing urban rail transit lines.

It’s always dangerous to generalize, but in the case of neighborhood opposition to new development, I can’t resist. In California, this neighborhood opposition is the prime reason why the state has under-produced housing since the 1970s, leading to economic inequality and environmental degradation — not to mention under-performing urban rail transit lines.

I should acknowledge that neighborhood opponents are armed with new tools to fight projects since the 1970s, such as the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and its more powerful state version, the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA).

But they also pressure local officials to restrict zoning to limit development and use voter initiatives to overturn project approvals, such as in Santa Monica recently on an Expo Line project and as is now brewing in Los Angeles with a proposed city-wide initiative to roll back density near transit.

So figuring out how to get ahead of this local dynamic and promote more transit-oriented development is key for anyone who cares about this issue.

Most of the complaints I hear from local opponents of new development relate to parking and traffic impacts, as well as to a generalized fear of losing the “character of the neighborhood.” It’s not hard to see why locals would feel this way. After all, most people move into a neighborhood because they like it as is, not because they hope it will change for the better with new development.

But at the same time, many new developments can bring benefits to the neighborhood, from new on-site amenities (like restaurants or retail), more tax dollars that can be spent on local services, a spiffier neighborhood with new construction, and sometimes features like parks and other improved infrastructure. Yet those benefits often seem outweighed by the fear of loss.

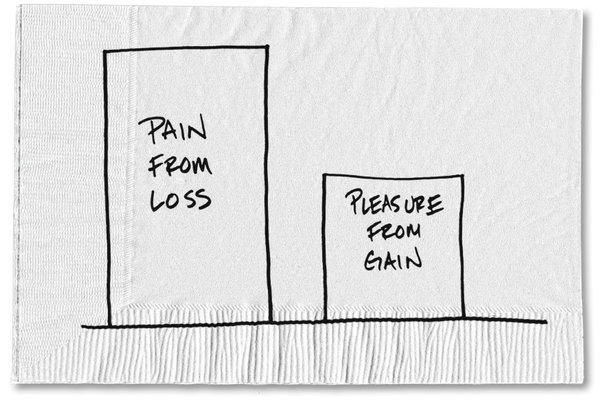

This is where some generalization on psychology might help, to try to explain what’s going on in the minds of local opponents and figure out how to address it if possible. It occurred to me that the dynamic at play may be what psychologists call “loss aversion.” Carl Richards in the New York Times described the phenomenon in the context of finances:

It turns out that most of us don’t like losing. In fact, it’s what the academics call loss aversion. We feel the pain of loss more acutely than we feel the pleasure of gain. In other words, we may like to win, but we hate to lose.

The psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky showed that even something as simple as a coin toss demonstrates our aversion to loss. In a recent interviews, Mr. Kahneman shared the usual response he gets to his offer of a coin toss:

“In my classes, I say: ‘I’m going to toss a coin, and if it’s tails, you lose $10. How much would you have to gain on winning in order for this gamble to be acceptable to you?’

“People want more than $20 before it is acceptable. And now I’ve been doing the same thing with executives or very rich people, asking about tossing a coin and losing $10,000 if it’s tails. And they want $20,000 before they’ll take the gamble.”

In other words, we’re willing to leave a lot of money on the table to avoid the possibility of losing.

So in the land use context, loss aversion tells us that no matter how great the benefits of new development might be, many local residents are more emotionally fixated on the certainty of what they will lose with a new project, which is relatively plain to see before them (i.e. the parcel that will be developed, or the current state of traffic or parking). Meanwhile, the benefits are uncertain, nebulous, and less emotionally impactful — and therefore not as valued.

So if we’ve identified this loss aversion dynamic correctly, how does that help us? Well, perhaps the same article on finance can help. In that article, Richards offers a hypothetical, in which people hold on to a money-losing stock because they’re afraid to sell and take a guaranteed loss. In the hypothetical, the stock is suddenly sold overnight and the owners now have the cash when they wake up. Would they re-buy the stock right away? Most people wouldn’t. The selling of the stock therefore creates a “reset” on their options that allows them to think more clearly.

How would this translate to land use? Well, you would need an equivalent “reset” on the parcel in question. If it’s an old structure, for example, a developer may want to get a permit to tear it down as soon as possible, while still seeking approval for the new project. Once the existing building is down, locals may feel less attached to the present condition and better able to imagine new buildings and benefits.

Likewise, if it’s an empty parcel, developers or local officials may want to immediately do something temporary with the site, like pop-up markets or retail stalls or temporary plazas. The hope would be to create life and activity in an otherwise empty space, in order to get the neighbors to feel comfortable with change and more open to the positives of the benefits rather than fixated on the negative.

These are just a few ideas that may counter the loss aversion of the locals. Of course, the other alternative is simply to beat opponents at their own game, through local organizing. But that path isn’t always possible or practical, and so addressing and “resetting” the concerns may provide a better option to encourage more housing production.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.