California has already achieved a landmark climate goal, we learned yesterday. Newly released data from 2016 by the California Air Resources Board show that the state’s greenhouse gas emissions decreased 2.7 percent to 429.4 million metric tons.

That number is significant because it’s below the 431 million metric tons the state produced in 1990, which is the level California law requires we achieve once again by 2020. And we’re now four years early on achieving that goal. Since our peak emissions in 2004, California has since dropped those emissions 13 percent.

Much of the reduction is due to significant increases in renewable energy production. Going forward, the next challenge will be a further 40 percent reduction below these 1990 levels by 2030, per SB 32 (Pavley, 2016). And that will require major decreases in emissions from the transportation sector — primarily through greater adoption of zero-emission vehicles.

Importantly, these emission reductions have occurred during a booming economy. The state has effectively de-linked economic growth from carbon-based energy. And all of this economic growth defies industry predictions back in 2006 when the 2020 goal in AB 32 was originally legislated.

As the Sacramento Bee reported at the time during the legislative debates:

[T]he measure [AB 32] is vigorously opposed by the California Chamber of Commerce and the petroleum industry.

”Climate change is real, and we do need to do things,” said Victor Weisser, president of California Council for Environmental and Economic Balance, which represents oil firms. ”But greenhouse gas emissions reduction in California is going to be very expensive.”

In short, industry was not pleased with the climate goals and believed they would cause economic calamity, as another Bee article related:

“We don’t think heavy-handed regulation and bureaucracy is necessary,” said Thomas Tietz, who heads the California Nevada Cement Promotion Council.

Backers say AB 32 would spur new technologies, but Tietz warned that such caps will backfire on the local economy. He said the bill would drive cement producers out of state and force California to import materials produced from countries or states with less stringent environmental rules.

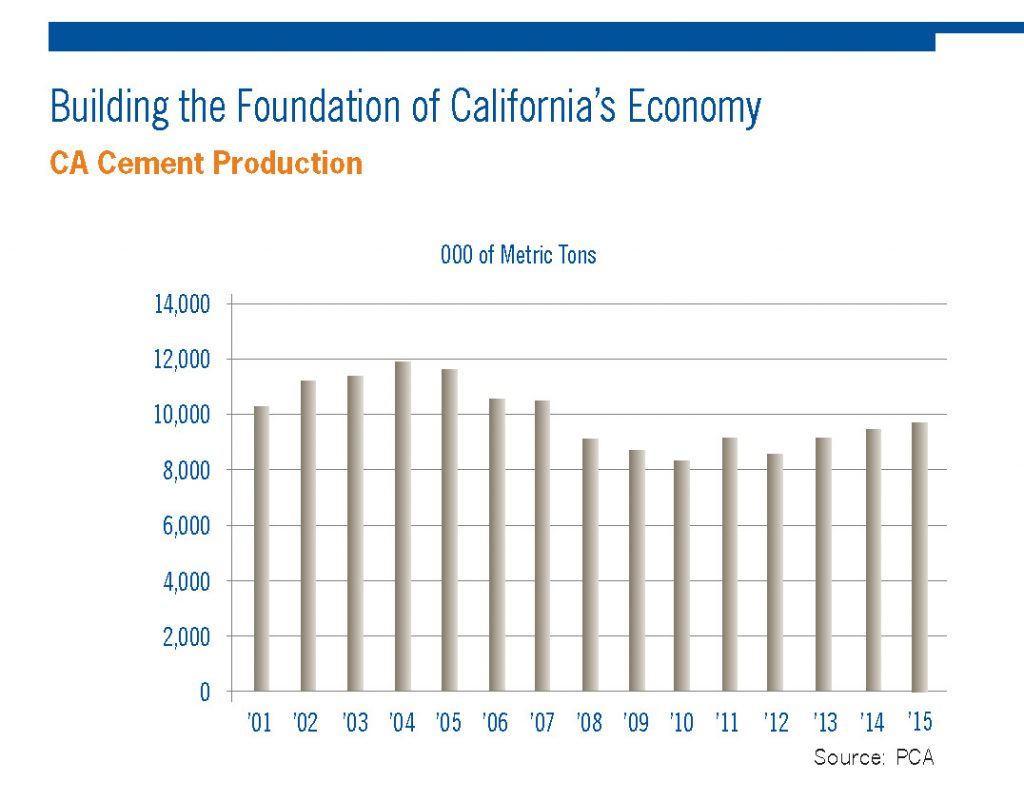

In retrospect, these predictions have not come true. Cement production hasn’t left the state, as industry figures show (although the sector hasn’t fully recovered since the last recession):

Overall, California’s success is a powerful example for the rest of the world and some important good news in the global fight against climate change.

Overall, California’s success is a powerful example for the rest of the world and some important good news in the global fight against climate change.

With much of the credit due to the proliferation of inexpensive renewable energy, the next challenge will be to ensure similar progress with zero-emission vehicle technology. And given the state’s track record on climate so far, we should be hopeful that similar success is achievable for 2030.