Most Americans probably think of state-sponsored racial segregation in this country in terms of Jim Crow-era segregated water fountains and schools, among other examples, which the Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional in 1954. But when it comes to residential segregation — communities that tend to be exclusively white, Latino, or African American, for example — many Americans might instead think like Chief Justice John Roberts, who described this type of segregation as de facto and not de jure (i.e. a function of official state policies). (Roberts used these terms in the 2007 Supreme Court case addressing two combined challenges to school integration policies, Meredith v. Jefferson County Board of Education & Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1).

The assumption that Roberts and others might have is that this segregation is the result of such factors as discriminatory lending practices or racist realtors, or perhaps through voluntary segregation by members of racial groups seeking to live amongst themselves. In short, anything but state action.

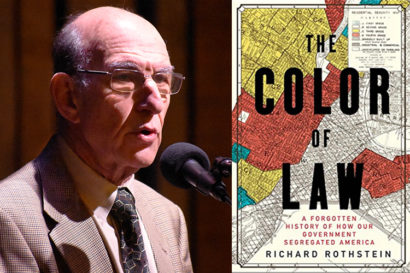

But Richard Rothstein, author of the landmark book The Color of Law, documents how residential segregation in America is not just the result of these de facto policies carried about by non-state actors.

As he described in a recent UC Berkeley podcast (transcript here), this segregation was instead deliberately fostered through government housing policies at the federal level, which led to post-World War II segregated suburbs across the country, including the San Francisco Bay Area and Los Angeles, among other California cities.

It’s worth listening (or reading the full transcript) for Rothstein’s description of this shameful and far-too-ignored history, the effects of which determine so much of the racial, economic and political landscape of the United States to this day.